Dr. Paul T. P. Wong’s autobiography, A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith, is published in weekly installments. Stay updated here.

“I suffer, therefore, I rejoice.” This paradoxical statement sums up my entire academic career in psychology. Burdened by a long history of suffering in China, growing up during Japanese occupation and civil war, and enduring decades of discrimination and marginalization in North America, it is inevitable that I look at life and psychology through a different prism (see my online autobiography).

It has been a lonely and difficult journey charting a new course as a bi-cultural psychologist (Wong, 2017a), but this cultural experience, coupled with my experience of suffering, has given me a unique insight into the psychology of well-being in adverse conditions.

Abram Amsel

Even as a graduate student, with all the options open to me in Canada as a National Research Council Award recipient, I chose to study frustration with Abram Amsel at the University of Toronto—the last standard bearer of learning theory and one of the most cited psychologists of his time (Papini, 2008). Looking back, I am sure that he would have been pleased if he lived to see that I am able to fulfill his lifelong wish to see his ideas and findings (Amsel, 1992) applied to the positive psychology of human resilience (Wong, 1995; Wong & Wong, 2006; Wong & Worth, in press).

I firmly believed then—and still believe now—that sustainable well-being depends on our ability to manage the ubiquitous presence of frustration and suffering and understand the deeper meaning of life in spite of a high misery index (Thin et al., 2017; Wong, 2017b, 2017c).

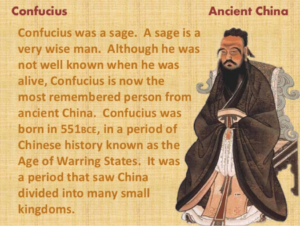

My overarching thesis in well-being research is that life can be best understood as a fractal pattern of Yin-Yang; only then can one discover deep meaning and joy in the midst of suffering. This position has come to be known as existential positive psychology (Wong, 2009a, 2016a) or the second wave of positive psychology (PP 2.0; Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2016; Wong, 2011). This dialectic approach to positive psychology was shaped by my upbringing in Chinese classics.

In short, since my graduate school days, I have felt that my unique calling was to study how to achieve well-being through overcoming adversities. My own moderate success in finding fulfillment in the midst of sufferings has reinforced this conviction that my mission in life is to bring happiness and meaning to all suffering people.

My Research Contributions

Generalized Persistence

My early research on persistence at the University of Toronto focused on the factors and process of effective coping with prolonged frustration and pain. This research can be considered as the first animal model of learned optimism and courage. Amsel and I have demonstrated that prior stress inoculation and a history of overcoming hardships can contribute to resilience, and resourcefulness (Amsel, 1992; Wong, 1995). This research was the first animal model of learned optimism and resourcefulness (Rosenbaum, 1990; Wong, Wong, & Scott, 2006; Wong & Worth, in press).

This research also has important implications for the positive psychology of grit. Duckworth’s (2016) conception of grit misses the mark by omitting courage—the touchstone of true grit (Wong, 2014a). For me, true grit is having the courage to do what is right and worthy in spite of fears, oppositions, obstacles, failures, and hardships. It is a virtuous lifestyle based on moral fortitude rather than just a motivation to achieve career success. I have used the following True Grit Check List (TGCL) for my clinical work (see Appendix A).

Research Panel of Biological and Behavioral Science at the National Institute of Mental Health.

All my research on generalized persistence convinces me that courage-based grit as measured by the TGCL would be a better predictor of resilience and achievement in real life as compared to persistence-based grit as measured by Duckworth and Quinn’s (2009) Short Grit Scale (GRIT-S). I welcome researchers to explore how the TGCL functions in a variety of situations as compared to the GRIT-S.

During the early 70s, I shared my research on generalized persistence with Martin Seligman and Steven Maier, making the case that animals and humans are naturally resilient; otherwise, they would have not survived—this is a reasonable assumption for positive psychology. I am most grateful that Steven Maier was sufficiently impressed with my research that he later nominated me to replace him on the Research Panel of Biological and Behavioral Science for five years at the National Institute of Mental Health. It was a very valuable experience working closely with leading researchers in psychology and biology.

Stress, Coping, and Meaning

Gary T. Reker

Later, my research effort was directed to effective coping in humans. Most of my human research was conducted at Trent University; I was privileged to be able to collaborate with Gary T. Reker and Edward Peacock on several projects during my Trent days. This research led to the development of a resource-congruence model (Wong, 1993) and the comprehensive Coping Schema Inventory (Wong, Reker, & Peacock, 2006).

As a result of my stress research, I was invited to be a guest editor of two special issues of Stress Medicine (Wong, 1990) and get involved with two international research projects, the first on work stress and well-being (Spector et al., 2001a, 2001b, 2002a, 2002b, 2004) and the second on cultural factors in well-being (Wong & Ujimoto, 1998; Ujimoto, Nishio, Wong, & Lam, 1993).

My social-personality research marked a transition from behavioral coping to cognitive and existential issues important for well-being. My demonstration of spontaneous attribution, both causal and existential (Wong, 1991; Wong & Weiner, 1981), initiated my 30 years of research on meaning seeking and meaning making (Reker & Wong, 1988; Wong & Fry, 1998; Wong, 2012a). My commitment to meaning research was due to my conviction that meaning is essential to positive mental health in the same way as our immune system is essential to our physical health (Wong, 1991). More recent research has confirmed my belief that any program to advance mental health and human flourishing needs to include meaning as an integral component (Batthyany & Russo-Netzer, 2014; Seligman, 2011).

My implicit theory approach to research on meaning (Wong, 1998) has also been extended to several countries (Kim, Lee, & Wong, 2005; Takano & Wong, 2004). The sources of meaning I discovered have also been replicated (Schnell, 2009). After many years of laboring in obscurity, my meaning research has finally gained wide recognition. I have been invited to contribute to numerous chapters in several international encyclopedias on positive psychology, meaning, and well-being (e.g., Wong, 2009a, 2013a, 2014b, 2016b, 2017c). In pursuit of global well-being, my cross-cultural research on effective coping, meaning, and positive psychology has also led to several publications (Leong & Wong, 2003; Wong, 2013a; Wong & Wong, 2006).

Most recently, I was asked to join an interdisciplinary research group known as the Virtue Scholars to work on the project of Virtue, Happiness, and Meaning of Life, funded by the John Templeton Foundation. It was a unique experience working with philosophers and theologians. My presentations at the Virtue Scholars meetings can be found on The Virtue Blog (Wong, 2015d, 2017d; Wong & Reilly, 2017).

Aging Well and Dying Well

The next research challenge for me was to wrestle with the existential concerns of aging and dying. In the area of positive aging, my main contribution was to reorient successful aging from biological factors to psychological, cultural, and spiritual factors (Reker & Wong, 1988, 2012; Wong, 1989; Wong & Watt, 1991). This research was supported by a large multiyear grant from the Social Science and Humanity Research Council. This research led to my appointment to the Advisory Council on Aging for Canada’s Federal Government for three years, representing the Province of Ontario.

My research on dying well (Wong, 2017e) and the development of the Death Attitude Profile-Revised (Wong, Reker, & Gesser, 1994); this scale has been translated into numerous languages and remains the most popular measure of death attitudes. I was pleased to have been invited by Robert Neimeyer to edit a special issue of Death Studies on death acceptance (Wong & Tomer, 2011).

Challenges and Achievements

Paul T. P. Wong with Chris Peterson

I have challenged many of the widely-held assumptions in American psychology because of my Chinese cultural background. My finding that internal and external locus of control are two separate dimensions challenges the Western conception of internal and external control as two opposite poles on the same continuum (Wong & Sproule, 1984). Similarly, I have questioned the binary approach to positive psychology and have argued that approach and avoidance are two dialectical interactive systems (Wong, 2012b). This line of reasoning has contributed to the emerging PP 2.0 (Ivtzan et al., 2016; Wong, 2009a, 2011, 2016d, Wong & Worth, in press). My dialectic dualistic approach to social-personality psychology and positive psychology have the potential of advancing research on global well-being in particular and mainstream psychology in general.

The above achievements were hard-earned. Even my most influential publications were initially harshly criticized and rejected. I was routinely criticized for not confirming to the “orthodox” tenets as declared by the leaders. I am most grateful to several influential individuals who have come to my aid and lent me their support during my uphill struggle as an outsider; these include the late Christopher Peterson, the late C. R. Snyder, the late Shane Lopez, and the late Joseph Fabry, who brought logotherapy to America.

Paul T. P. Wong with Joseph Fabry in his hom

The above recollection gives me a sense of survival guilt, but it also gives me the impetus to continue the gigantic task of integrating East and West, positive psychology and existential psychology. I may not live long enough to accomplish this task, being an 80-year-old cancer survivor, without institutional support and graduate students.

I hope that the International Network on Personal Meaning (INPM; www.meaning.ca)—which I created in 1998 as a big tent for all those interested in meaning-oriented research and interventions (Wong, 2014c)—will continue this mission long after I am gone. A related plan is to give all my research ideas free to those interested in doing research with my ideas or instruments; the only precondition is that they become a member of INPM. Those interested in my offer may contact me by email (drpaulwong@gmail.com) with the subject line: “Your Research Ideas.”

My Contributions to Meaning-Centered Interventions

Since all my research was to discover how to help people in their struggle for survival, healing, and well-being, my psychological practice is naturally integrated with my own research and the larger research literature.

After four decades of meaning-centered scientific research, I was able to distill these findings into principles and practices which can be immediately put to use by anyone aspiring to live a fulfilling and meaningful life. These principles have been validated not only by empirical research, but also in the crucible of suffering in my own life journey.

Theoretical Background

Although my meaning-centered therapy (MT) is rooted in empirical research, its theoretical framework is drawn from a variety of rich resources in order to shed light on the dark side of human existence and people’s yearning for meaning and spirituality.

We are now living in a turbulent and dangerous time. International terrorist attacks are on the rise. Threats of wars are looming over several flashpoints. In the USA, troubles are mounting with racial tension, polarized political views, and a toxic climate of chaos and distress.

What can psychologists do to reduce the level of evil and suffering on the one hand, and enhance the level of well-being and social harmony on the other hand? MT represents my attempt to address this twofold challenge.

Initially, MT was based on Frankl’s (1985) logotherapy, which was developed as a spiritual therapy to maintain human dignity and sanity in Nazi concentration camps. Later, MT was influenced by key philosophers from the East and West, such as Confucius and Aristotle, and humanistic-existential founders, Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow, and Rollo May. In addition, MT is influenced by Christ’s teaching on sacrificial love, grace, and forgiveness, and Buddha’s teaching on compassion and mindfulness.

MT begins with the assumption that spirituality is an integral part of personhood (Sue, Bingham, Porche-Burke, & Vasquez, 1999; van Deurzen & Adams, 2011) and that life has ultimate meaning and purpose (Frankl, 1985; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Following Aristotle’s (1908) virtue ethics, Confucius’ heaven-ordained Dao (Zhongyong) or innate Luminosity (The Great Learning), and Frankl’s (1985) will to meaning, MT further assumes that the higher innate purpose for meaning, love, and virtue needs to be discovered and actualized in order for people to feel at home their element and become fully functioning decent human beings.

Frankl (1985) has made a compelling case that such assumption is adaptive in surviving trauma and suffering. Braaten and Huta (2016) have demonstrated empirically the adaptive benefits of such a worldview. Conversely, MT assumes that psychological difficulties and social disorders are likely to occur when people are spiritually deprived, when their basic spiritual needs for meaning, love, and significance are not met. Thus, recovery and positive mental health depend on equipping clients with the knowledge and skills to pursue meaningful life goals and cope with life’s demands.

Frankl (1985) has made a compelling case that such assumption is adaptive in surviving trauma and suffering. Braaten and Huta (2016) have demonstrated empirically the adaptive benefits of such a worldview. Conversely, MT assumes that psychological difficulties and social disorders are likely to occur when people are spiritually deprived, when their basic spiritual needs for meaning, love, and significance are not met. Thus, recovery and positive mental health depend on equipping clients with the knowledge and skills to pursue meaningful life goals and cope with life’s demands.

In sum, the ethos of MT is one of spirituality and virtue; it emphasizes the common humanness or the universal spirituality as the foundation for living a good life in a just, compassionate, and harmonious society. In other words, we can make life better for all people if we all follow human nature’s higher angels of seeking self-transcendence, rather than the base instincts of selfish competition for power, possession, and fame (Wong, 2016e).

Assessment Instruments

In the process of pursuing meaning research, I have developed numerous instruments that have been translated in several languages: Death Attitude Profile-Revised (Wong, Reker, & Gesser, 1994), Personal Meaning Profile (Wong, 1998); The Stress Appraisal Measure (Peacock & Wong, 1990); Coping Schemas Inventory (Wong, Reker, & Peacock, 2006); Meaning Mindset Measure (Wong, 2012c); Life Orientation Scale (Wong, 2014d); and Life Attitude Scale (Wong, 2009b). These measures have been widely used by both researchers and clinicians. My latest empirically validated instrument is the Self-Transcendence Measure (Wong et al., in progress; see Appendix B).

In my clinical practice, I have also developed numerous assessment instruments, such as Emotional Health Checklist (2015a), PURE Test (2013b) and the Search for Meaning Screen Test (2015b). These clinical tools can be tested empirically to advance meaning research in a positive spiral of advancing well-being. The Search for Meaning Screen Test (2015b) (see Appendix C) is of particular significance for future meaning research, because it makes a clear functional distinction between fulfillment-based search for meaning and problem-based meaning quest.

In both my clinical practice (Wong, 1998b, 2015c) and my Meaningful Living Project (www.inpm.org), various assessment tools have been developed to monitor people’s initial condition and progress in healing and personal growth. I welcome other researchers to validate these instruments.

Meaning Therapy in Practice

MT (Wong, 2010, 2016d) is also known as meaning-centered counseling and therapy. It was first based on Frankl’s logotherapy, but later extended to integrate with cognitive-behavioral therapy and positive psychotherapy (Wong, 2016d). Thus, MT employs a pluralistic approach (Cooper & Dryden, 2016) to therapy that tailors the intervention to each client to best resolve their issues and, at the same time, meet their fundamental human needs for meaning and relationship. MT represents a comprehensive way to address all aspects of meaning-in-life concerns in a supportive therapeutic relationship (Vos et al., in press). The motto for MT is, “Meaning is all we have; relationship is all we need.” MT assumes that when these two essential human needs are met, individuals are more likely to cope better with their predicaments and live a more rewarding life. When there is deficiency in these two areas, people will more likely experience difficulties in life.

MT operates from the conceptual framework of PURE (Wong, 2012d) which is an acronym for (1) Purpose, the motivational dimension of values, life direction, intentions, needs, wants, and desires; (2) Understanding, the cognitive dimension of coherence, comprehension, and sense-making; (3) Responsibility, the behavioral dimension of self-determination, commitment, and action; and (4) Enjoyment, the emotional dimension of satisfaction and sense of significance.

Purpose, understanding, and enjoyment have been widely accepted as the components of meaning-in-life in meaning research (Martela & Steger, 2016). Responsibility is implied in research on self-determination, self-actualization, and self-efficacy, all factors essential for meaning and well-being. Thus, all effective therapies are predicated on the client’s willingness to take control of their lives and assume responsibility for their well-being. The only difference is that MT makes personal responsibility to choose one’s preferred future and cultivate the authentic self the front and center of therapeutic conversations.

MT favours a psycho-educational approach that helps clients understand the vital role of meaning and purpose in healing, recovery, and well-being (Wong, 2012d). It appeals to the client’s better angels and their sense of responsibility to make the proper use of their freedom to pursue what really matters and what constitutes a good life of meaning, virtue and happiness (Martela, 2017; Ryan & Deci, 2010; Wong, 2015d).

MT also makes extensive use the ABCDE framework for coping with adversities and improving well-being in difficult times (Wong & Wong, 2012) which stands for (1) Accepting and confronting reality—the reality principle; (2) believing that life is worth living—the faith principle; (3) committing to goals and actions—the action principle; (4) discovering the meaning and significance of self and situations—the aha! principle; and (5) evaluating the above—the self-regulation principle.

In addition to learning the proactive resource-congruency coping, clients learn meaning-focused coping (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004; Wong, 2017c), where clients are guided to (1) adopt a defiant attitude towards adversity (courage); (2) reframe problems into a larger context of meaning (self-transcendence); (3) reframe problems as challenges (re-appraisal); (4) seek benefits in suffering (existential coping); (5) let go what cannot be changed (existential coping); (6) re-author and connect one’s life story to a meta-narrative; and (7) encourage goal-striving of something bigger than oneself.

Summer Institute 2017

The best way to capture the ethos of MT is to help our clients become fully functioning human beings who know how to embrace and transform the dark side of life and, at the same time, actualize their potentials so that they give their unique gifts to society and enjoy a mature happiness that is characterized by inner peace and harmony (Wong, 2017f; Wong, Bowers, & Shekhawat, in progress).

I am so pleased that through our MT workshop at the biennial INPM Summer Institute, we have trained numerous mental health professions, such as psychologists, psychotherapists, MDs, social workers and chaplains. I am now working with many Summer Institute alumni to apply the MT to correctional services, palliative cares, addiction recovery, training of physicians, spirituality & the whole person health, etc. My vision is to train an army of mental health professionals to implement the adaptive benefits of meaning.

The Meaningful Living Project

My endeavour to advance positive mental health at the grassroots level is through Meetups, as I have reported on Positive Psychology News Daily (Wong, 2012e). The latest report on this project can be found in Wong (2016f). The principles and practices of meaningful living are captured in the following practical questions discussed at the Meetups:

- How can I know my true self in a digital world?

- How do I decide on what really matters in this brief life?

- How can I make sense of this crazy, upside-down world?

- How can I discover beauty, meaning, and significance in everyday small things?

- How do I exercise freedom and responsibility in spite of limitations and fate?

- How do I apply the PURE model of meaning-making in my life?

- How can I find enduring happiness even in the midst of sufferings?

- How do I use the ABCDE model of coping to build resilience and grit?

- How can I remain optimistic in hopeless situations?

- How do I live life to the fullest the Yin-Yang way?

- How do I connect with others and a higher power through self-transcendence?

- How can I make the most of this life through the double-vision strategy?

- How do I realize my dreams without the necessary resources and opportunities?

- How do I develop a spiritual or moral compass to navigate perilous waters?

- How can I transform my ordeals into a hero’s journey?

The above lessons are framed according to the main thesis of PP 2.0 that a complete scientific account of well-being needs to consider the dark side of human nature and the human experience, just as a science of physical health can only be based on the assumption that we all live in an environment full bacteria, viruses, and toxins (Thin et al., 2017; Wong, 2017b). According to this perspective, we need to simultaneously measure the misery index (Hanke, 2014), stress levels, and well-being indicators in order to more realistically assess the well-being of individuals and nations.

I also propose that the best preparation to live a meaningful life in a dangerous time like ours is to arm people with mental toughness consisting of courage, faith, endurance, and self-transcendence (Wong, 2016e; 2017f, Wong & Worth, in press). An important research question is whether such individuals are more resistant to stress and depression and more likely to enjoy mature happiness in difficult times, as compared to individuals only equipped with the scientific knowledge of wellbeing and signature character strengths.

Meaningful Living Meetup Group

The take-home message for Meaningful Living Meetups is to embrace suffering as one’s best teacher. Often, people cannot discover their true humanity and spiritual strengths without going through tribulations and despair. Paradoxically, the greatest human achievements and fulfillment often come from the deepest suffering.

With adequate funding, this meaning-centered grassroots positive mental health movement (www.inpm.org), has the potential to advance global well-being even in the poorest neighborhoods, because it makes optimal use of people’s inborn spiritual yearnings and innate capacities for meaning seeking and meaning making.

Conclusion

A Different Orientation

Against the mighty current of American psychology, I have chosen a path less traveled and swum against the tide in my pursuit of well-being because I have followed a different drummer (Wong & Tweed, in press), pursuing a vision based on (1) the dialectics of Daoism that “happiness is the absence of the striving for happiness” (Zhuangzi莊子; Tao Te Ching道德經); (2) the teaching of Confucius that a good life can be achieved through cultivating and fulfilling one’s inborn good nature or humanness (Ren 仁) (Zhongyong中庸; Daxue大學; Analects論語); and (3) Frankl’s (1985) will to meaning through transcending and transforming sufferings for something greater than oneself. My research findings on effective coping and the vital role of meaning in resilience and well-being (Wong, 2014b; Wong & Ujimoto, 1998) lends some credence to this new paradigm of studying global well-being.

Against the mighty current of American psychology, I have chosen a path less traveled and swum against the tide in my pursuit of well-being because I have followed a different drummer (Wong & Tweed, in press), pursuing a vision based on (1) the dialectics of Daoism that “happiness is the absence of the striving for happiness” (Zhuangzi莊子; Tao Te Ching道德經); (2) the teaching of Confucius that a good life can be achieved through cultivating and fulfilling one’s inborn good nature or humanness (Ren 仁) (Zhongyong中庸; Daxue大學; Analects論語); and (3) Frankl’s (1985) will to meaning through transcending and transforming sufferings for something greater than oneself. My research findings on effective coping and the vital role of meaning in resilience and well-being (Wong, 2014b; Wong & Ujimoto, 1998) lends some credence to this new paradigm of studying global well-being.

Anthony Marsella

In recent days, we have daily witnessed on television the increasingly toxic political and social milieu, the rising violence on the national and international stages, and the ugliness of the narcissistic pursuit of hedonism, wealth, and self-aggrandizement (Gerhardt, 2010; Kranish & Fisher, 2016; McAdams, 2016). Perhaps the time is right to consider the adaptive benefits of the above alternative vision of global well-being based on justice, compassion, social interests, and peace, in which all people can enjoy a decent life (Marsella, 2014, 2017).

An Alternative Model

Seligman’s (2004, 2011) positive psychology movement has already transformed the landscape of psychology and has left a remarkable impact on all sectors of society; however, the changing social climate and recent advances in positive psychology research indicate that we may want to consider the adaptive benefits of PP 2.0, which incorporates humanistic values and existential insights (Wong, 2011, Wong & Roy, 2017; Wong & Tweed, in press) and stresses the mature happiness of inner peace and harmony (Delle Fave et al., 2016; Wong, 2017b).

My research on Chinese positive psychology (2009c, 2016c) and tragic optimism (Wong, 2009b; 2017b) suggests that mature happiness is derived from spiritual and psychological maturity based on acceptance, faith, and inner integration of both the Yin-Yang elements of life; as such, it may be called noetic or spiritual happiness. Future research will determine whether noetic happiness is most enduring and most resistant to disruptions in life as compared to the other two major types of happiness—hedonic and eudaimonic. Research will also show that the meaning-mindset (Wong, 2011), self-transcendence measure (Wong et al., 2017), and spirituality (Daaleman & Frey, 2004) are the best predictors of mature happiness.

In view of the above, I propose that this alternative model for global well-being can complement Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model to provide more pathways to flourishing. I also propose that the following attitudes and values are needed to create mature happiness and a society of justice and compassion where all people can flourish, regardless of their personal identity, economic status, and nationality. This alternative model may be represented by the acronym CasMac:

- Courage to embrace our dark side, make positive changes in our lives, and stand for what is right.

- Acceptance of what cannot be changed and what is beyond our control.

- Self-transcendence to overcome setbacks, obstacles, and our internal/external limitations.

- Meaning-mindset as a lens to look at life as a whole and present situations.

- Appreciative attitude towards life and other people.

- Compassion for all living things, including oneself.

One can readily see that this CasMac is heavily influenced by Chinese classics on acceptance (Wong, 2009c, 2016c) and research on self-acceptance (Bernard, 2013); Adler’s (1964) teaching on courage for social interest (Yang, Milliren, & Blagen, 2010); Frankl’s emphasis on the pursuit of a meaning-mindset (Wong, 2012c) and self-transcendence (Wong, 2016e); and Buddhist teachings on appreciation and compassion (for a brief introduction, see Buddha Dharma Education Association, 2008) and Gilbert’s (2009) The Compassionate Mind; also see Wong (2006).

My hypothesis is that in a time of peace and prosperity, PERMA is a better pathway to achieve flourishing. However, during a time of war and deprivation, CasMac is a better way. Similarly, I predict that PERMA may be better suited to the individualistic culture of the West, whereas CasMac may be better for the collective culture of the East. I hope that collaborative research (Wong, 2016g) from different cultures and different theoretical orientations will test these hypotheses regarding global well-being and flourishing.

I have finally reached the point that I can put together all my insights gained from different strands of my research on resilience and well-being into a coherent model for global well-being that integrates East and West (Wong, Bowers, & Shekhawat, in progress). My future research will focus on global well-being and world peace. To me, life is more than just a marathon race on paved roads, but a dangerous jungle adventure, which demands courage, endurance, and cooperation.

The following quote, a part of my keynote to the International Conference of Wellbeing in Pakistan, summarizes my vision for a sustainable global well-being and world peace (Marsella, 2014):

“There may be different psychological models and pathways toward the attainment of well-being, depending on different countries and cultures, but there is enough scientific research that allows us to identify essential elements of both the subjective nature and the objective conditions of well-being.

In the West, people tend to emphasize hedonic happiness; in the East, the emphasis is on inner peace and relational harmony. Whatever one’s cultural background, well-being includes such essential elements as life satisfaction, contentment, gratitude, meaning, purpose, hope, faith, and love. These elements elevate us to live at the spiritual level and make us fully functioning human beings.

We also know that the objective conditions that contribute to well-being include education, living conditions, and a democratic political-economic situation. These conditions need to ensure personal freedom, self-determination, justice, equal rights, education, and opportunities for all to develop their potentials in order to serve the common good.

The road to a high level of well-being is not an easy one in a hostile environment of discrimination, oppression, and aggression. It can be a long and difficult journey that demands both individual and collective efforts. It will take discipline and perseverance to co-create a safer and better world for us and our children. May this conference inspire a generation of researchers in the pursuit of global well-being for both the self and society.”

References

- Adler, A. (1964). Social interest, a challenge to mankind. New York, NY: Capricorn Books.

- Amsel, A. (1992). Frustration theory: An analysis of dispositional learning and memory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Aristotle. (1908). The Nicomachean ethics. (W. D. Ross, Trans.). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Batthyany, A., & Russo-Netzer, P. (Eds.). (2014). Meaning in existential and positive psychology. New York, NY: Springer.

- Bernard, M. E. (Ed.). (2013). The strength of self-acceptance. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Braaten, A., & Huta, V. (2016). How fundamental worldviews about life and the world relate to eudaimonia, hedonia, and the experience of meaning. Paper presented at the 9th Biennial International Meaning Conference, Toronto, ON.

- Buddha Dharma Education Association. (2008). Unit six: The four immeasurables. BuddhaNet. Retrieved from http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhism/bs-s15.htm

- Cooper, M., & Dryden, W. (2016). The handbook of pluralistic counselling and psychotherapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Daaleman, T. P., & Frey, B. B. (2004). The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: A new instrument for health-related quality of life research. Annals of Family Medicine, 2, 499-503.

- Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Wissing, M. P., Araujo, U., Solano, A. C., Freire, T., … & Nakamura, J. (2016). Lay definitions of happiness across nations: The primacy of inner harmony and relational connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(3), doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00030.

- Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Duckworth, A., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2). doi:10.1080/00223890802634290

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 55, 745-774.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Gerhardt, S. (2010). The selfish society: How we all forgot to love one another and made money instead. London, UK: Simon & Schuster.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind. London, UK: Constable.

- Hanke, S. H. (2014). Measuring misery around the world. CATO Institute. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/measuring-misery-around-world

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2016). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

- Kim, M., Lee, H-S., & Wong, P. T. P. (2005, August). Meaning of life according to Koreans: The Korean Personal Meaning Profile. Poster presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

- Kranish, M., & Fisher, M. (2016). Trump revealed: An American journey of ambition, ego, money, and power. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Leong, F. T. L., & Wong, P. T. P. (2003). Optimal human functioning from cross-cultural perspectives. In B. Walsh (Ed.), Counseling psychology and optimal human functioning (pp. 123-150). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Marsella, A. J. (2014). War, peace, justice: An unfinished tapestry. Alpharetta, GA: Aurelius Press.

- Marsella, A. J. (2017, April 10). World order and disorder: The “games” and “gambles” of life and lives. Trascend Media Service. Retrieved from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2017/04/world-order-and-disorder-the-games-and-gambles-of-life-and-lives/

- Martela, F. (2017). Can good life be measured? The dimensions and measurability of a life worth living. In G. Brulé, & F. Maggino (Eds.), Metrics of subjective well-being: Limits and improvements (pp. 21-42). Cham, Switzerland, Springer.

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531-545.

- McAdams, D. P. (2016, June). The mind of Donald Trump: Narcissism, disagreeableness, grandiosity—a psychologist investigates how Trump’s extraordinary personality might shape his possible presidency. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/06/the-mind-of-donald-trump/480771/

- Papini, M. R. (2008). Integrating learning, emotion, behavior theory, development, and neurobiology: The enduring legacy of Abram Amsel (1922-2006). The American Journal of Psychology, 121(4), 661-669.

- Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1990). The Stress Appraisal Measure (SAM): A multidimensional approach to cognitive appraisal. Stress Medicine, 6(3), 227-236.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Oxford University Press

- Reker, G. T., & Wong, P. T. P. (1988). Aging as an individual process: Towards a theory of personal meaning. In J. E. Birren, & V. L. Bengston (Eds.), Emergent theories of aging (pp. 214-246). New York, NY: Springer.

- Reker, G. T., & Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Personal meaning in life and psychosocial adaptation in the later years. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 433-456). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rosenbaum, M. (1990). Learned resourcefulness: On coping skills, self-control, and adaptive behavior. New York, NY: Springer.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). To be happy or to be self-fulfilled: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. In S. Fiske (Ed.), Annual review of psychology (Vol. 52). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews Inc.

- Schnell, T. (2009). The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (SoMe): Relations to demographics and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 483-499. doi:10.1080/17439760903271074

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Poelmans, S., Allen, T. D., O’Driscoll, M., Sanchez, J. I., Siu, O. L., Dewe, P., Hart, P., … & Yu, S. (2004). A cross-national comparative study of work/family stressors, working hours, and well-being: China and Latin America vs. the Anglo world. Personnel Psychology, 57, 119-142.

- Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sanchez, J. I., O’Driscoll, M., Sparks, K., Bernin, P., Büssing, A., Dewe, P., Hart, P. … & Yu, S. (2001a). Do national levels of individualism and internal locus of control relate to well-being: An ecological level international study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 815-832.

- Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sparks, K., Bernin, P., Büssing, A., Dewe, P., Lu, L., Miller, K., Renault de Moraes, L. … & Yu, S. (2001b). An international study of the psychometric properties of the Hofstede Values Survey Module 1994: A comparison of individual and country/province level results. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50, 269-281.

- Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sanchez, J. I., Sparks, K., Büssing, A., Dewe, P., Lu, L., Miller, K., De Moraes, L. R. … & Wong, P. T. P. (2002a). The pitfalls of poor psychometric properties: A reply to Hofstede’s reply to us. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 174-178.

- Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sanchez, J. I., O’Driscoll, M., Sparks, K., Bernin, P., Büssing, A., Dewe, P., Hart, P. … & Yu, S. (2002b). A 24 nation/territory study of work locus of control in relation to well-being at work: How generalizable are western findings? Academy of Management Journal, 45, 453-466.

- Sue, D. W., Bingham, R. P., Porche-Burke, K., & Vasquez, M. (1999). The diversification of psychology: A multicultural revolution. American Psychologist, 54(12), 1061-1069.

- Takano, Y., & Wong, P. T. P. (2004, July/August). Meaning of life according to a Japanese sample. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Thin, N., Tarragona, M., Wong, P. T. P., Jarden, R., Bartholomaeus, J., & Jarden, A. (2017). Book review for International Journal of Wellbeing. Estes, Richard J., and M. Joseph Sirgy [eds] (2017) The Pursuit of Human Well-Being: The Untold Global History. Dordrecht: Springer. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7(1), 84-92. doi:10.5502/ijw.v7i1.636

- Ujimoto, K. V., Nishio, H. K., Wong, P. T. P., & Lam, L. (1993). Cultural factors affecting the self-assessment of health satisfaction. In R. Masi, L. Mensah, & K. McLeod (Eds.), Health and culture: Explaining the relationships (pp. 229-240). Toronto, ON: Canadian Council on Multicultural Health.

- van Deurzen, E., & Adams, M. (2011). Skills in existential counseling and psychotherapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Vos, J., Cooper, M., Hill, C. E., Neimeyer, R. A., Schneider, K., & Wong, P. T. P. (in press). Five perspectives on the meaning of meaning in the context of clinical practices. Journal of Constructivist Psychology.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1989). Personal meaning and successful aging. Canadian Psychology, 30, 516-525.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (1990). Two special issues on advances in measuring stress. Stress Medicine, 6(2-3).

- Wong, P. T. P. (1991). Existential vs. causal attributions: The social perceiver as philosopher. In S. L. Zelen (Ed.), New models, new extensions of attribution theory (pp. 84-125). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1993). Effective management of life stress: The resource-congruence model. Stress Medicine, 9(1), 51-60.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1995). A stage model of coping with frustrative stress. In R. Wong (Ed.), Biological perspectives on motivated activities (pp. 339-378). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998a). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998b). Meaning-centered counselling. In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 395-435). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2006). The nature and practice of compassion: Integrating Western and Eastern positive psychologies [Review of the book Compassion: Conceptualizations, research, and use in psychotherapy]. PsycCRITIQUES, 51(25). doi:10.1037/a0002884

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009a). Existential positive psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 361-368). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009b). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany, & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009c). Chinese positive psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 148-156). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85-99.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012a). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012c). What is the meaning mindset? International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 4(1), 1-3.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012d). From logotherapy to meaning-centered counseling and therapy. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 619-647). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012e, Jun. 22). Giving positive psychology away: Meaningful living meetups. Positive Psychology News Daily. Retrieved from http://positivepsychologynews.com/news/paul-wong/2012062222849

- Wong, P. T. P. (2013a). Positive psychology. In K. Keith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of cross-cultural psychology. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2013b). The PURE test. Meaningful Living Project. Retrieved from http://inpm.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Meaningful-Living-Project-Exercise-6-PUREtest.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014a). The positive psychology of grit: The defiant power of the human spirit [Review of the film Unbroken]. PsycCRITIQUES, 60(25). doi:10.1037/a0039390

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014b). Meaning in life. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 3894-3898). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014c, March 31). My vision for international psychology and the Meaning Conference. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/my-vision-for-international-psychology-and-the-meaning-conference/ (There should be an official link to the Bulletin of International Psychology)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014d). Viktor Frankl’s meaning seeking model and positive psychology. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in existential and positive psychology (pp. 149-184). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015a). The Emotional Health Checklist. Dr. Paul Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/dr-wongs-psychological-tests/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015b). The Search for Meaning Screen Test. Meaningful Living Project. Retrieved from http://inpm.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Meaningful-Living-Project-Screening-Text.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015c). Meaning therapy: Assessments and interventions. Existential Analysis, 26(1), 154-167.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015d, December). The meaning hypothesis of living a good life: Virtue, happiness, and meaning. Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina. (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Existential positive psychology. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/179/158

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Humanistic theories in psychopathology. In H. L. Miller (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of theory in psychology (pp. 438-441). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016c). Chinese positive psychology revisited. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/174/157

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016d). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016e). Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178/141

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016f). Meaning centered positive group intervention. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 423-445). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016g, January). Proposed guidelines for collaborative research. Dr. Paul Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/proposed-guildences-collaborative-research

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017a, September). International psychology and I: A reflection. International Psychology Bulletin, 21(3).

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017b, May 16). Courage, faith, meaning, and mature happiness. Positive Living Newsletter. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/inpm-presidents-report-may-2017

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017c). Coping and stress. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (886-890). New York, NY: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017d, February 2). Bad and good self-transcendence. The Virtue Blog. Retrieved from https://thevirtueblog.com/2017/02/02/bad-and-good-self-transcendence/ (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017e). Death and dying. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 965-967). New York, NY: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017f, May 16). Courage, faith, meaning, and mature happiness. Positive Living Newsletter. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/inpm-presidents-report-may-2017

- Wong, P. T. P., Bowers, V., & Shekhawat, P. S. (in progress). Meaning, mature happiness and an attunement model of well being. In N. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness and empathy in contemporary society. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Fry, P. S. (Eds.). (1998). The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P., Peacock, E., Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., & Kjell, O. (in progress). Self-Transcedence Measure.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Reilly, T. (2017, May 2). Frankl’s self-transcendence model and virtue ethics. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/frankls-self-transcendence-model-and-virtue-ethics (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P., Reker, G. T., & Gesser, G. (1994). Death Attitude Profile – Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death (DAP-R). In R. A. Neimeyer (Ed.), Death anxiety handbook: Research, instrumentation, and application (pp. 121-148). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

- Wong, P. T. P., Reker, G. T. & Peacock, E. (2006). The resource-congruence model of coping and the development of the Coping Schema Inventory. In P. T. P. Wong, & L. C. J., Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 223-283). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Roy, S. (2017). Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology. London, UK: Routledge. (Partially supported by the research grant on Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life from the John Templeton Foundation in support of the humble approach to positive psychology.)

- Wong, P. T. P., & Sproule, C. F. (1984). Attributional analysis of locus of control and the Trent Attribution Profile (TAP). In H. M. Lefcourt (Ed.), Research with the locus of control construct: Limitations and extensions (Vol. 3; pp. 309-360). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Tomer, A. (Guest Eds.). (2011). A special issue on death acceptance. Death Studies, 35(2).

- Wong, P. T. P., & Tweed, R. (in press). Positive psychology in North America. In E. C. Chang, C. A. Downey, H. Yang, I. Zettler, & M. Muyan (Eds.), The international handbook of positive psychology: A global perspective on the science of positive human existence. New York, NY: Springer. (Partially supported by the research grant on Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life from the John Templeton Foundation in support of the humble approach to positive psychology.)

- Wong, P. T. P., & Ujimoto, K. V. (1998). The elderly: Their stress, coping, and mental health. In L. C. Lee, & N. W. S. Zane (Eds.), Handbook of Asian American psychology (pp. 165-209). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Watt, L. (1991). What types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging? Psychology and Aging, 6(2), 272-279.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Weiner, B. (1981). When people ask “Why” questions and the heuristic of attributional search. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(4), 650-663.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (2012). A meaning-centered approach to building youth resilience. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 585-617). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P., Wong, L. C. J., & Scott, C. (2006). Beyond stress and coping: The positive psychology of transformation. In Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 1-26). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Worth, P. (in press). The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity [Special issue]. Psychology and Education, 54(3/4).

- Yang, J., Milliren, A., & Blagen, M. (2010) The psychology of courage: An Adlerian manual of healthy social living. New York, NY: Routledge.

Appendix A: The True Grit Check List (TGCL)

P. T. P. Wong (2014)

| 1. | Are you willing to defy authority in order to stand up for what is right? | Yes | No |

| 2. | Have you ever risked inconvenience or danger in order to help others? | Yes | No |

| 3. | Have you ever overcome obstacles and oppositions to pursue a worthy goal? | Yes | No |

| 4. | Have you ever taken on a task in spite of fear of failure and opposition? | Yes | No |

| 5. | Are you willing to endure hardships and setbacks in order to accomplish your life goal? | Yes | No |

| 6. | Are you willing to risk rejection in order to be true to your core value or belief? | Yes | No |

| 7. | Have you ever suffered because you chose principle over expediency? | Yes | No |

| 8. | Have you ever endured great difficulties and adversities in completing a big project? | Yes | No |

| 9. | Do you have something that is bigger than personal success and worth dying for? | Yes | No |

| 10. | Have you ever accomplished anything that initially seemed impossible? | Yes | No |

Appendix B: Self-Transcendence Measure-Brief (STM-B)

P. T. P. Wong, E. Peacock, O. Kjell, I. Ivtzan, & T. Lomas (2017)

Please respond to the following statements by circling the most appropriate response to the scale, from 0 (not at all characteristic of me or my beliefs) to 4 (a great deal characteristic of me or my beliefs).

| 1. | My life is meaningful because I live for something greater than myself. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 2. | My suffering is more bearable when I believe that it is for my family, friends, and/or for a higher purpose. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 3. | I enjoy the process of striving towards excellence in what matters. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 4. | At my funeral, I want to be remembered as a decent human being who cared about others. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 5. | A worthy lifelong pursuit ought to have some intrinsic value—something that is good in its own right. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 6. | What matters most to me in life is the contribution I make to society. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 7. | I focus on discovering the potential meaning in every situation. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 8. | I devote my life to pursuing the ideals of beauty, goodness, and truth. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 9. | I develop my full potential in order to give my best to benefit society. | 0 1 2 3 4 | |

| 10. | I am more motivated by doing something meaningful than by the prospect of receiving external rewards. | 0 1 2 3 4 |

Appendix C: The Search for Meaning Screen Test (SMST)

Paul T. P. Wong (2013)

The Search for Meaning Screen Test was designed to provide an index of both the positive and negative reasons for meaning quest. If you check Yes to more than 12 of the 24 questions, you will benefit from participate in the meaningful living project.

| 1. | Are you seeking a deeper understanding of the real you? | Yes | No |

| 2. | Do you want to better understand your place in the world? | Yes | No |

| 3. | Do you want to determine what really matters in life? | Yes | No |

| 4. | Do you want to learn more about your strengths and weaknesses? | Yes | No |

| 5. | Do you want to learn how to live well and die well? | Yes | No |

| 6. | Are you seeking confirmation of your calling? | Yes | No |

| 7. | Do you want to learn how to live an authentic, vital and rewarding life? | Yes | No |

| 8. | Do you want to learn how to achieve a high level of well-being? | Yes | No |

| 9. | Do you want to pack more meaning and purpose in your life? | Yes | No |

| 10. | Are you seeking to understand the mysteries and paradoxes of life? | Yes | No |

| 11. | Are you engaged in a spiritual quest for God or a higher power? | Yes | No |

| 12. | Do you want to make a positive contribution to the world? | Yes | No |

| 13. | Are you dissatisfied with your pleasant job or life situation? | Yes | No |

| 14. | Are you uncomfortable in your own skin? | Yes | No |

| 15. | Are you sick and tired of being YOU? | Yes | No |

| 16. | Do you feel that your striving is pointless and futile? | Yes | No |

| 17. | Do you still feel empty and unhappy in spite of your successes? | Yes | No |

| 18. | Are you going through a stage of life transition? | Yes | No |

| 19. | Do you have problems with close relationships? | Yes | No |

| 20. | Do you feel alienated and displaced? | Yes | No |

| 21. | Are you worried about change and the uncertainties of your future? | Yes | No |

| 22. | Are you afraid of death and dying? | Yes | No |

| 23. | Are you struggling with your personal issues? | Yes | No |

| 24. | Are you troubled by the question why bad things happen to you? | Yes | No |

The first 12 questions are concerned with positively oriented search for meaning, while the next 12 questions are concerned with negatively oriented search for meaning.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2017). Reflections on my psychology career: Where I come from, and where I am going. A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.