Authors

Co-authored with Roger Tweed, Ph.D., Kwantlen Polytechnic University, Surrey, BC, Canada.

Abstract

Positive psychology in America can be traced back to humanistic psychology, founded by Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, with its emphasis on self-actualization and self-transcendence. Martin Seligman’s positive psychology (PP 1.0) focuses on experimental studies of what is good and right in human being. American PP 1.0 is dominant by three major research programs: virtues in action, flourishing through PERMA intervention, and various happiness-enhancing variables, such as gratitude. In Canada, V. Huta’s main contribution is eudemonic happiness. P. T. P. Wong’s research marked the emerging of second wave positive psychology (PP 2.0), which is characterized by two distinctive elements: (a) existential positive psychology with suffering as the foundation for happiness and wellbeing, and (b) indigenous psychology with the Yin-Yang concept as an Asian view of wellbeing.

Historial Background to Positive Psychology in North America

Humanistic Psychology

The story of positive psychology (PP) in America begins long prior to the modern movement called PP. Humanist psychologists were the first psychologists who focused on the positive side of people—their innate goodness and natural tendency towards the self-actualization of their potentials. Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow were the leading figures in this movement. Beginning as a reaction against the determinism of psychoanalysis and behaviorism in the 1950s and 60s, humanistic psychology advocated the need to study the whole person and the subjective perception and phenomenological experience of individuals. It is known as the third force in the history of psychology. From this holistic perspective, behavior cannot be fully understood simply by objective observation apart from the subjective meaning of individuals and their inter-subjective verification. Humanistic psychologists maintain that, ultimately, people are motivated by their beliefs and innate needs more than by their circumstances.

It is interesting that despite Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi’s (2000) disparaging remark about humanistic psychology, it remains an influential aspect of PP (Froh, 2004). In fact, more than half of the positive psychologists covered in this chapter have been influenced by humanistic psychology. It may be argued that a PP inspired and influenced by humanistic psychology has more depth and enduring influence than a PP without a rich humanistic heritage.

For humanistic psychologists (Maslow, 1954; Rogers, 1961/1995), the responsible use of freedom is essential to become fully functional human beings. They argued that people can achieve their vision of the good life only when they can responsibly exercise their freedom to choose their own authentic path and achieve their life goals. Thus, their true happiness is a by-product of self-determination and self-actualization. Humanistic psychology began to decline in importance as a movement in the 80s, mostly because of its lack of experimental research that impacts mainstream psychology (Wong, 2011a).

Positive Psychology 1.0 in the U.S.A.

During his 1998 presidency of the American Psychological Association (APA), Martin Seligman launched his PP movement as a new science (Seligman, 1998, 1999a). After his presidency ended, he continued to promote PP through recruiting both established and elite young researchers and through the provision of research grants to scholars interested in the field. We refer to this brand of PP as PP1.0.

The initial topics that Seligman proposed for PP—positive states, positive traits, and positive institutions (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000)—are indeed worthy topics, and a number of American scholars were already working on these. Therefore, it is not so much Seligman’s original ideas as his ability to attract the cream of the crop in mainstream psychology that accounts for the success of PP 1.0. Perhaps it would be more accurate to describe Seligman’s PP movement not as a new science, but instead as a new research community dedicated to advance Seligman’s vision of PP 1.0, which focuses on positivity and the positivist paradigm of science.

The field of PP has had its share of detractors, including Lazarus (2003), who attracted much attention with criticisms such as his assertion that positive psychologists “attack the psychology of the past to create the illusion that what they offer is new and different” (p. 107). James Coyne has also criticized PP and particularly the evidence base for some PP interventions not only in peer-reviewed work (Coyne, Tennen, & Ranchor, 2010), but also through his influential PLOS blog (e.g., Coyne, 2014a, b). For a comprehensive critique of PP, see Wong and Roy (2018). On a more popular level, Barbara Ehrenreich (2010) argued that pressuring people to be happy can do more harm than good, and her claims are supported by recent research, such as Oettingen’s findings that some forms of positive thinking predict maladaptive consequences (for a review, see Oettingen, 2014).

In spite of the detractors, the field advanced in a number of ways and continued to gather adherents and institutional support. For example, a U.S. based organization called the International Positive Psychology Association (IPPA) was formed in 2007, and the organization’s first Congress occurred in 2009 in Philadelphia. There is now a Ph.D. program in PP (e.g., Claremont Graduate School) and many students also obtain a Ph.D. in PP topics in a typical graduate program in psychology (e.g., social, clinical). The Masters of Applied Positive Psychology (MAPP) program at the University of Pennsylvania is a liberal arts program, and it does not require any specific undergraduate psychology courses as prerequisites. The curriculum does include one research methods course, but it does not require any coursework in other foundational areas of psychology. In spite of its lack of psychology training, many MAPP graduates market themselves as experts in the science of happiness and well-being. This situation is even more concerning due to the proliferation of PP post-graduate certificate programs. These programs are typically offered by positive psychologists or MAPP graduates to train coaches and consultants and promise to provide a potentially lucrative career for certificate providers and graduates. Though these programs contribute in some ways to Miller’s (1969) campaign to give psychology away so that the public can use it, they also produce some graduates with minimal scientific skills who may misapply or overstate the power of PP interventions, thus turning PP into a pseudoscience.

Along with this growth in PP, the field has become closely associated with business. Some business schools are beginning to integrate PP into their curricula. Claremont Graduate School even offers a Ph.D. in positive organizational psychology. For most PP associations, including the IPPA, both the membership and conference programs reflect a mixture of academics, business coaches, and consultants. This inclusion indicates that many people in the business community have bought into the vision of PP. One negative aspect of this development is that the scientific basis of PP is becoming diluted with premature applications and over-generalizations at the workplace (Wong, Ivtzan, & Lomas, 2016).

In some ways, Seligman’s message of positivity also resonates with the same crowd that was once attracted to humanistic psychology. It may be argued that there has always been a trait of optimism and positive thinking in the American psyche (Ehrenreich, 2010). In spite of the rich heritage of humanistic-existential psychology, Seligman decided to distance his PP movement (PP 1.0) from this heritage (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). This decision has rippling effects that eventually required a course correction in the second wave of PP (PP 2.0; Wong, 2011b), which attempts to reclaim PP (Wong, 2011b) and integrate it with humanistic-existential psychology (Wong, 2009a, 2011b). What separates PP 2.0 from PP 1.0 is not just the recognition of positive potentials in negative emotions, but, more importantly, the emphasis on humanistic values, the dark side of human existence, and dialectical principles (Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2016; Wong, 2011b)

Positive Psychology in Canada

By virtue of its proximity to the United States and a common heritage, Canada has always struggled to maintain its unique cultural identity as a mosaic society. This is also the case with respect to PP. In spite of the dominant influence of American PP, Canada is the home of existential PP (Wong, 2009a) and PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011b). Drawing upon European existential thoughts—especially Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy—and Chinese dialectical philosophy (Wong, 2009b, 2016a), Wong developed PP 2.0 and promoted it through the Biennial International Meaning Conferences based in Canada (www.meaning.ca/conference).

PP 2.0 is inherently cross-cultural, existential, and much more complex than the initial tenets of positive emotion, positive traits, and positive institutions. The starting point of PP 2.0 is embracing the dark side of human existence as the proper context for research and understanding human flourishing and well-being, just as the medical science starts by accepting the reality that we live in a world full of bacteria and viruses. The aim of PP 2.0 is to bring out the best in individuals and society in spite of inevitable human suffering and evil. Secondly, PP 2.0 favors the dialectical principle of yin and yang as a more realistic way to approach negative and positive human experiences than the binary or dichotomous way.

Consequently, PP 2.0 does not confine itself to neutral or positive territories; it covers the totality of human experiences and is relevant to under-privileged and suffering people. Finally, PP 2.0 emphasizes the importance of the internal and external validity of variables pertaining to the good life based on both the existential and cross-cultural literature. In sum, PP 2.0 reflects the mosaic culture of Canada, particularly with its European and Asian influences.

On the global stage of PP, two competing forces are often at work in various countries. Canada provides a good example of the clashing of two competing visions. On the one hand, there is the dominating force of PP from America, with all its big names, big money, influential publications, and evidence-based PP interventions, which may not always be culturally appropriate. An important element in this mix is the training of foreign students in America through the MAPP program previously described. Often, graduates from MAPP promote their coaching business with science as their calling card, and establish a local Positive Psychology Association as their guild; in other words, they serve as “colonizers” of American PP (for a critique, see Wong & Roy, 2018 ).

On the other hand, there are indigenous positive psychologists trained in their own country and shaped by their own culture. They struggle to establish their own indigenous identity by developing culturally sensitive research programs and interventions often with two handicaps—without the necessary funding and under the huge shadow of American PP.

The dominant force of American PP and the home-grown force of indigenous PP have not found a way to work together to advance PP and benefit their country. The difficulty of merging these two forces was clearly evident in the early days of the Canadian Positive Psychology Association (Wong, 2013a).

Abraham H. Maslow (1908-1970)

Abraham Maslow is included in this chapter not only because he first coined the term “positive psychology” in his 1954 book Motivation and Personality, but also because of his profound impact on PP. His is most known for his theory of the hierarchy of needs, which has been influential in psychology, management, sociology, and psychiatry.

Maslow (1961) rejected European existentialism and advocated the need to “push toward the establishment of another branch of psychology, the psychology of the fully evolved and authentic self and its ways of being” (p. 56). He coined the term the “Third Force” to identify this new branch of psychology.

Maslow is perhaps best known for his theory of the hierarchy of needs, which consists of five levels: (a) physiological needs, (b) safety and security needs, (c) the need for love and belonging, (d) esteem needs, and (e) the need for self-actualization. The first four needs are deficient needs or “D-motives” because people are motivated to fill the deficiency in these needs. Self-actualization motives represent growth-oriented needs at the “being” level; therefore, they are called the “B-values” or “B-motives.” Wong (2005) pointed out that the hierarchy model does not mean a rigid stage model, in which one needs to complete one level in order to move to the next level; in fact, these needs can be met simultaneously or in a reverse manner. For example, some people may value their calling as more important than their personal safety. The bottom line is that Maslow (1954) believed that the unifying motivational principle is to pursue higher needs.

In his old age, Maslow was puzzled by two questions: First, he recognized that some of his self-actualized friends were “prima donnas” who were self-centered and could not work together. Second, he wondered what motivated people who have already actualized. His solution to these problems was to add self-transcendence as the last or the highest stage of human development. Thus, in order to become fully functioning human beings, self-actualizers need to continue to be driven by meta-motivation and devote their lives to helping others actualize themselves. He also expanded the list of B-motives, which now includes the following: truth, goodness, beauty, wholeness, aliveness, uniqueness, perfection, completion, justice, simplicity, richness, effortlessness, playfulness, and self-sufficiency. Maslow (1971) died before he could fully develop his revised needs hierarchy (Koltko-Rivera, 2006).

Maslow’s theory of human motivation emphasized the inner push towards self-actualization, self-transcendence, and the peak experience. Maslow (1954) described the peak experience as a “tremendous intensification of any of the experiences in which there is loss of self or transcendence of [self]” (p. 165; emphasis original); it includes a sense of rapture, wonder, and ecstasy, which can transform people’s view of themselves and the world around them. Maslow’s main contribution was his emphasis on the positive existential givens and the human potential for the transcendental, spiritual level of human existence. His theory remains one of the most complete and influential theories of PP, a theory that is based on his noble and optimistic view of human nature and human potentials.

With respect to research, Maslow was opposed to the atomistic, dichotomist thinking that is still prevalent in PP. Much like William James’s (1912) “radical empiricism,” Maslow (1970) believed that it was possible to integrate experiential subjectivity with experimental objectivity; he wanted to “integrate the healthily animal, material, and selfish with the naturalistically transcendent, spiritual, and axiological” (p. 5). Throughout his research career, Maslow attempted to humanize and trans-humanize the non-personal science so that it can account for the unique and holistic human experiences (Maslow, 1966/2002).

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Csikszentmihalyi worked with Seligman to facilitate the PP movement beginning in the late 1990s (Csikszentmihalyi & Nakamura, 2011), but his major contributions to the movement began long before those years. One of Csikszentmihalyi’s greatest contributions to PP has been his concept of flow. He wrote about this concept in both academic publications (e.g., 1975) and also in his popular book on the topic (1990). His early descriptions of flow varied somewhat, but twenty-five years after his first publication, Csikszentmihalyi (2000) described flow as a “state of optimal experience that people report when they are intensely involved in doing something that is fun to do” (p. 381).

PP has gone astray, in some ways, by not heeding some of the realizations Csikszentmihalyi developed as part of his studies of flow. In particular, he noticed that lasting pleasure and growth fail to emerge from seeking purely short term happiness. In contrast, he argued that enjoyment can often emerge from circumstances that are not pleasant and are even painful, such as climbing a mountain during a snow storm, perfecting a difficult dance move though repeated practice, or playing an extended chess match in spite of fatigue and headache (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). A second aspect of his flow theory particularly relevant to PP is the fact that his work on flow was originally published in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975). In that paper, he reported that this flow experience was indistinguishable from some of the peak experiences described by Maslow. Both the place of publication and the parallel he draws to Maslow’s idea highlight the close link between his work and the tradition of the humanistic psychologists.

Another contribution of Csikszentmihalyi was his methodological emphasis on getting out of the typical lab while still using methods accepted within the field of psychology. He was one of the first, if not the first, researchers to conduct experience sampling research using beepers to remind participants to record their subjective experiences (Csikszentmihalyi, Larson, & Prescott, 1977); this again reflects the influence of humanistic psychology.

He also realized the value in studying the negative aspects of human experience in addition to the positives. He collaborated on work with mood swings in adolescents (Larson, Csikszentmihalyi, & Graef, 1980), television addiction (Kubey & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), and aversive aspects of self-awareness (Csikszentmihalyi & Figurski, 1982). In view of the above, it is puzzling why went he along with Seligman (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) in explicitly distinguishing PP from its humanistic heritage.

This brief review demonstrates ways that Csikszentmihalyi took a PP perspective long before PP 1.0 was officially launched by Seligman in 1998. PP 1.0 might have been stronger if more of the adherents of this new community of scholars had learned the lessons of Csikszentmihalyi’s earlier research.

Martin E. P. Seligman

Seligman’s early and continuing leadership within the PP movement gives him a position of significant influence. Several concerns arise from Seligman’s powerful role. His early emphasis on happiness may have had the benefits of attracting many people to the PP community and appealing to a consumerist society, but it may have also triggered a backlash and contributed to the development of PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011b). Some research suggests that well-being is predicted more strongly by building meaning and other eudaimonic outcomes rather than by a focus on building happiness (Huta & Ryan, 2010; Steger, Kashdan, & Oishi, 2008). Admittedly, Seligman’s later work, such as his book entitled Flourish (2011), introduced his PERMA model which explicitly denotes that well-being includes life meaning (the “M” in PERMA), yet even within that book, meaning received relatively little attention. The emphasis on happiness, which was admittedly much stronger in his early work in PP, can crowd out attention to other elements of well-being.

Furthermore, even after his conversion to a broader definition of well-being, Seligman does not justify why his vision of well-being deserves pre-eminence over that of other theorists or even other cultures (Wong, 2011c), and that highlights another problem with his powerful role and, more broadly, the centrality of American leadership within PP. The centrality of American scholars in his PP community may hinder the development of indigenous positive psychologies.

In the final analysis, we all owe a great debit to Seligman because without his vision, leadership, and entrepreneurial success in building a community of PP scholars, we would not be contributing to this International Handbook. The past 20 years have witnessed a great deal of growing pains and expansion in PP. We believe that history will recognize his great contributions to psychology in spite of some mistakes along the way.

Christopher Peterson

Christopher Peterson co-taught possibly the first university course in PP ever in 2003 and then published possibly the first full-length textbook on PP (Peterson, 2006), but looking back on the movement, some of his other contributions may be even more significant.

Peterson deserves to be remembered for at least two major contributions to PP: his attention to virtue and character strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) and his interpersonal impact. Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000), when they introduced PP, argued for three major foci: positive subjective states (e.g., happiness), positive traits (e.g., virtues), and institutions facilitating these. Thereafter, the bulk of PP researchers and practitioners seemed focused on the first of these three: positive subjective states. In contrast, Peterson helped to keep attention on positive traits including virtues and character strengths. He collaborated on developing a modern classification system for virtues and character strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). His classification system gained much traction possibly not only because of the quality of his work, but also because his collaboration with the VIA Institute in developing and distributing a strengths questionnaire allowed research with large and culturally diverse samples (e.g., McGrath, 2015; Peterson, Park, Pole, D’Andrea, & Seligman, 2008).

Peterson’s second major contribution was interpersonal. Peterson was fascinating in part because he didn’t feel a need to pretend to always be happy even though he was a positive psychologist. As he said about himself, “I do my share of complaining, and I roll my eyes much more frequently than I smile” (Peterson, 2006, p. 19). Nevertheless, many scholars have reported being inspired and moved by Peterson’s commitment to the well-being of others (e.g., Brunwasser & Gillham, 2014; Park & Seligman, 2013; Wright, 2012). For these qualities, he was respected and loved by many psychologists, including those who are critical of PP.

Peterson was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Network on Personal Meaning (INPM) in 2012. Unfortunately, he died prematurely about two months after the 2012 Meaning Conference. His keynote speech at the Meaning Conference was later published (Peterson & Park, 2014), which may be his last journal publication. It is worth noting that, in this paper, they emphasized the need to include meaning as an outcome measure and that a valid meaning measure should include sources of meaning and purpose (Schnell, 2009; Wong, 1998).

Edward Diener

Ed Diener can accurately be portrayed as a courageous proponent of the need to study well-being scientifically. From very early in his career, he was warned that the scientific study of happiness was both impossible and not worthy of study. Now, many years later, it is his research on subjective well-being for which he is most highly regarded, not his other research on the “approved” list of topics.

Diener has worked consistently to make his research and other work relevant to the needs of not only the privileged, but to others as well. For example, Diener collaborated on a book (Diener, Lucas, Schimmak, & Helliwell, 2009) describing ideas for applying research findings to develop social policy that could improve well-being for millions of people. In related work, he also argued that governments should consistently survey the psychological well-being of their populace to measure the impact of their policies and also to identify subgroups with the greatest needs (Diener & Diener, 2011).

Diener has also drawn attention to cultural differences in causes of well-being and even in the nature of well-being (e.g., Diener et al., in press), and he has also at least occasionally given credit to humanistic psychologists for the relevance of their ideas to modern explorations of well-being (Diener, 1984, 2008; Tay & Diener, 2011), though we could argue that the humanist psychologists deserve even more credit.

One concern with Diener’s work has been his emphasis on mostly hedonic indicators of well-being (frequent positive affect, infrequent negative affect, and life satisfaction; Diener, 1984, 2000). Though these are important indicators of well-being, this approach over-represents hedonic indicators of well-being (Proctor, Tweed, & Morris, 2015) even though eudaimonic orientations seem particularly important for longer lasting well-being (Huta & Ryan, 2010; Steger, Kashdan, & Oishi, 2008). More recently, Diener (Su, Tay, & Diener, 2014), like Seligman (2011), has broadened his focus to a wider set of indicators of well-being. In spite of this concern, Diener’s research is highly valued and has relevance beyond the academy. These, and his courageous perseverance in the face of potential career harm, deserve to be remembered.

Sonja Lyubomirsky

Sonja Lyubomirsky began her PP work with a paper describing a measure of happiness (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999). Then, for the rest of her career, she has focused mainly on exploring the causes of happiness. One of the most significant contributions from Lyubomirsky has been her work popularizing the nature of PP interventions. She has written popular books on strategies for increasing happiness (Lyubomirsky, 2008, 2013). In this way, she has become a significant face of PP for many people who lack training in the topic. In some ways, though, in spite of the benefits she has provided to the populace, her prominent role may have exacerbated the tendency for people to attend to mainly the hedonic-oriented values of PP rather than the work on eudaimonia.

Another very significant contribution has been Lyubomirsky’s early (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999) and ongoing (Lyubomirsky, Dickerhoof, Boehm, & Sheldon, 2011) awareness that people may differ in terms of activities and achievements that produce hedonic well-being. In recent years, she has had an unusual sensitivity to the fact that PP interventions may be ineffective if implemented with the wrong population at the wrong time (Lyubomirsky et al., 2011; Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013).

Barbara L. Fredrickson

Fredrickson is most noted for her broaden and build theory (Fredrickson, 1998). That theory suggests that positive emotions help overcome tendencies toward a narrow focus of attention and thereby help people see a broader range of possible thoughts and actions available to them. The theory also suggests that this broadening then helps people build resources and move toward emotional well-being (Fredrickson, 1998). She has been successful in spreading this message beyond the community of PP scholars to a wider scientific audience (e.g., Fredrickson, 2003).

Fredrickson’s work has not been without controversy. Some work on the relation between positive emotion and health has been criticized (Heathers, Brown, Coyne, & Friedman, 2015; Kok & Fredrickson, 2015), as has her claim that a critical ratio of at least 2.9 positive emotions to negative emotion demarks a flourishing individual (Brown, Sokal, & Friedman, 2013; Fredrickson & Losada, 2005) and also some work on well-being and genomics (Brown, MacDonald, Samanta, Friedman, & Coyne, 2014; Fredrickson et al., 2013). In spite of these controversies, she remains one of the most creative and influential positive psychologists.

In more recent work, like many of the other positive psychologists mentioned here, Fredrickson seems to have reduced her focus on hedonia and taken more interest in eudaimonia including work on meditation (van Cappellen, May, Isgett, & Fredrickson, 2016), mindfulness, and even meaning (Garland, Farb, Goldin, & Fredrickson, 2015). In this sense, her trajectory within PP is somewhat like that of Seligman and Diener, with an early focus on hedonia and a later transition toward attention on a broader set of indicators of well-being.

Richard M. Ryan

Richard Ryan is Professor at the Institute for Positive Psychology and Education at the Australian Catholic University and Research Professor in Psychology at the University of Rochester in New York. He is co-developer (with Edward Deci) of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), a theory of human motivation that has generated a great deal of research and has been applied to many areas, including education, clinical practice, sports psychology, and eudaimonia (Ryan, Curren, & Deci, 2013; Taubes, 2010).

Self-determination is based on intrinsic motivation, such as feelings of autonomy and competence. Patterson and Joseph (2007) were correct in seeing a connection between SDT and Rogers’ person-centered theory because they provide similar perspectives and meta-theoretical assumptions. There is a great deal of cross-cultural data supporting the universality of the human needs for autonomy, agency, and freedom (Chirkov, Ryan, & Sheldon, 2011). When these basic needs are frustrated or thwarted, people will become more vulnerable to mental illnesses (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

SDT was around in the 1980s, well before Seligman launched his brand of PP in 1998. Ryan and Deci were not included in the group that Seligman called the “Senior Scholars” in Seligman’s original network of PP (Seligman, 1999b). Yet, SDT remains the only general theory of human motivation that has received considerable empirical support and provided a very helpful conceptual framework to enhance eudemonic happiness, well-being, and personal growth and, at the same time, reduce vulnerability. The strength of SDT lies in its recognition of the positive potentials of human nature and people’s basic needs for freedom, autonomy, and relationships.

Carol D. Ryff

Carol Ryff is Director of the Institute on Aging and Hilldale Professor of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ryff has never been part of the PP community and has been critical of PP (Ryff, 2003). Yet, her research on psychological well-being, and positive health has been widely cited because of its broad scholarship, solid empirical foundation, and cross-cultural contribution. Although she is mostly known from her theory and research on well-being, she has also been impactful in intervention strategies and educational programs (Ryff, 2014a, b; Ryff et al., 2014; Ruini & Ryff, 2016).

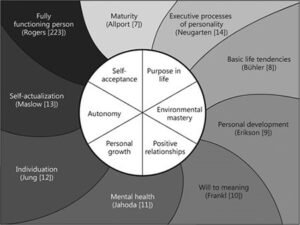

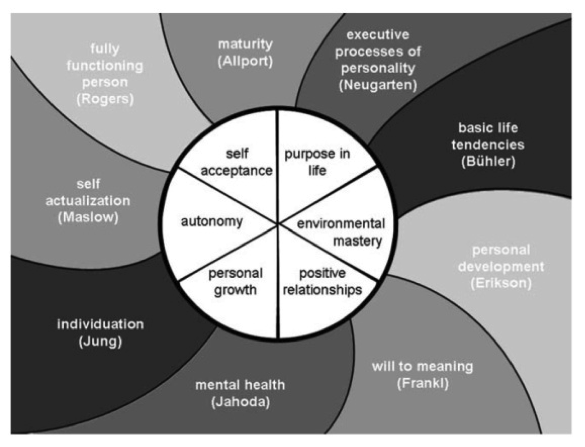

Multidimensional Assessment of Psychological Well-Being

Ryff’s (1989, 2014a) research on the six domains of psychological well-being was both ground-breaking and seminal. Her model was based on integrating ideas from existential, humanistic, developmental, and clinical psychology. She benefited from their deep insights of the bright side of human nature, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The six main components of psychological well-being (Ryff, 2014a)

Different from most PP assessment tools, which are based on short and simple self-reports (for a critique, see Wong & Roy, 2018), Ryff’s well-being scale is multidimensional and lengthy; the long form of the scale consists of 84 questions and the medium form 54 questions (Seifert, 2005). It has been translated to more than 30 different languages and generated more than 500 publications because of its theoretical rootedness and universal appeal.

Consistent with Aristotle (1908) and existential positive psychology (Frankl, 1985; Wong, 2009a), Ryff emphasized “know thyself and become what you are” as the key to her eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being (Ryff & Singer, 2008). Ryff also provided biological correlates (cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, immune) of a eudaimonic well-being that is rich in meaning and purpose, quality relationships, and continued growth (Ryff, 2012; Ryff & Singer, 1998).

Holistic Multidisciplinary Approach to Human Resilience

Another theme in Ryff’s research has been human resilience—the human capacity to maintain or regain well-being in the face of cumulative adversity and underlying neurobiology. Her holistic multidimensional research integrates several levels of analysis: sociodemographic characteristics, psychosocial resources, life stresses, health behaviors and practices, neurobiological risk and protective factors, and health outcomes with extensive psychosocial and biomarker assessments (Ryff, 2014b). The main findings from longitudinal studies of aging have shown that those who remain purposefully engaged with life experience numerous health benefits. Such findings demonstrate the importance of promoting eudaimonic well-being and resilience across a broad segment of the population, including the socioeconomically disadvantaged and those suffering from cancer and child abuse (Ryff, 2014a, 2016; Ruini & Ryff, 2016).

Cross-Cultural Sensitivity

Since 1995, Ryff and her team have researched factors that influence health and well-being from middle age through old age via a study called MIDUS (Mid-Life in the U.S. National Study of Americans). She has also been involved in a parallel study in Japan. She has directly compared well-being, resilience, and adult development in Japan and the U.S. (Ryff et al., 2015). Thus, her third major contribution to PP is that she is keenly aware that well-being is rooted in culture, and hence interventions need to be sensitive to cultural contexts (Ryff et al., 2014). For example, she and her associates (Curhan et al., 2014) discovered that Japanese people were less affected by negative emotions than their American counterparts. This difference can be easily understood in terms of yin and yang differences in coping. Eastern cultures are more attuned to the tragedies and hardships of life and have learned to cope with patience and endurance—the yin aspects of adaptation and are less likely to expect to immediately eradicate every life problem (Lin, 1935; Tweed, White, & Lehman, 2004).

Robert A. Emmons

Robert Emmons is a Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Davis and the founding editor-in-chief of The Journal of Positive Psychology. He is the world’s leading scientific expert on gratitude (Emmons, 2007, 2013). However, to him, gratitude is more than just a valid instrument to enhance happiness, because “gratitude heals, energizes, and transforms lives” (Emmons, 2016) and the nature of gratitude is spiritual (Emmons, 2010; Emmons & Hill, 2001). The PP literature often ignores Emmons’s major contributions to spirituality and meaning. In this chapter, we want to highlight these larger contributions that pave the way for PP 2.0.

Spiritual Beliefs and Strivings Hold the Key to Well-Being

Like Viktor Frankl (1985), Emmons recognizes that spirituality is a core dimension of being human. This deeper understanding of human nature elevates the academic discourse from the simple empirical question of what exercises may enhance well-being and happiness to the fundamental theoretical question of how to be becoming fully functioning human beings with spiritual strivings towards the sacred (Emmons, 2005).

Consistent with humanistic-existential thinking, Emmons (2005) emphasizes the vital role of religion and spirituality in human existence by “establishing goals and value systems that potentially pertain to all aspects of a person’s life” (p. 731). By framing religion and spirituality in terms of goal-directed behavior, he makes a compelling case that meaning is not a matter of subjective feeling or thinking, but a matter of goal-directed actions towards ultimate concerns (Emmons, 1986, 1999).

Ultimate concerns are “concerns over ultimate questions of meaning and existence, purpose and values” (Emmons, 2005, p. 737), which express themselves in personal goals. These spiritual goals are characterized by striving to transcend the self and serving something greater than the self, by seeking a relationship with a higher power, and by integrating the individual with “larger and more complex units” (Emmons, 2005, p. 736); these characteristic are highly similar to Wong’s conceptualization of self-transcendence (Wong, 2016b).

Emmons’ meaning-centered approach to personality and well-being is evident in his definition of self-identity in terms of the “pursuit of personally significant goals in general, and goals of a religious and spiritual nature in particular” (Emmons, 2005, p. 732). His research has demonstrated that people with spiritual goals “tend to experience their lives as worthwhile, unified and meaningful” (Emmons, 1999, p. 104).

Finally, consistent with PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011b), Emmons has recognized that implicit worldviews and values systems—which give rise to spiritual strivings—are essential not only to human flourishing, but also to resilience in coping with adversity and traumas. For instance, Emmons’ (2005) research with persons with neuromuscular disease showed that when their strivings were centered on the sacred, “they [were] likely to experience life as fulfilling, meaningful, and purposeful, even in the face of a deteriorating and disabling physical condition” (p. 742).

Gratitude is an Expression of Spirituality

Gratitude is a natural expression of a spiritual life—a life that is fully aware of God or a Higher Power as the source of life and all its blessings. When gratitude is employed as an instrument to enhance personal happiness, such as paying a gratitude visit or writing a gratitude letter, it does not always work because such exercise depends on each individual’s personal and cultural context (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013). Furthermore, a life focused merely on pursuing happiness, whether through gratitude or other means, can undermine the very happiness that is being sought (Martin, 2008). However, when gratitude is cultivated as a spiritual practice, it works in every culture, because it has been an ancient spiritual discipline practiced in every religion. The simplest form of such practice is to count our blessings on a daily basis, not just for being alive, but also for the many blessings we have received (Wong, 2016c).

Emmons (2010) was especially correct in pointing out that the nature of gratitude has two components: “[1] It’s an affirmation of goodness. We affirm that there are good things in the world, gifts and benefits we’ve received. … [2] We recognize the sources of this goodness as being outside of ourselves. … I think true gratitude involves a humble dependence on others: We acknowledge that other people—or even higher powers, if you’re of a spiritual mindset—gave us many gifts, big and small, to help us achieve the goodness in our lives” (para. 9-10).

Contributions to PP 2.0

Emmons (2005) is fully aware that “what contributes to the self-perceived well-being of an individual might be detrimental to the well-being of others” (p. 742). Thus, a truly meaningful and fulfilling life is not just about the individual, but also about others and future generations. Emmons is also cognizant that spiritual striving towards the sacred may entail guilt and shame, but “dissatisfaction can be desirable if it is used as fuel for constructive life change. Even usually positive characteristics can have harmful consequences” (p. 742).

Finally, in agreement with Viktor Frankl (1985), Emmons (2005) believes that direct pursuit of happiness can be counterproductive, because “research indicates that happiness is often a by-product of participating in worthwhile projects and activities that do not have as their primary focus the attainment of happiness” (p. 733). Like Carol Ryff, he is an important researcher responsible for the transition from PP “as usual” to PP 2.0.

Notable Positive Psychologists in Canada

Canada is not short of positive psychologists influential in research and/or teaching. Tayyab Rashid (www.tayyabrashid.com) is well known for his research on positive psychotherapy (Rashid & Howes, 2016). Robert J. Vallerand (www.lrcs.uqam.ca/rjvaller_en.htm), Professor and the Director of the Research Laboratory on Social Behavior at the Université du Québec à Montréal, is known for his research on the psychology of passion (Vallerand, 2015). Chris Davis of Carlton University is known for his research on meaning-making in tragic situations (Davis, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Larson, 1998). Another major player in meaning research is Gary Reker (Reker, Peacock, & Wong, 1987). Finally, Kenneth Hart is known for being the first Canadian professor to develop a university course on PP (Hart & Sasso, 2011). However, we decided to focus on Paul Wong for his influence on the PP 2.0 movement and Veronika Huta for her systematic study on eudaimonic happiness because of their potential impact on the future of PP in Canada.

Paul T. P. Wong

Suffering is both the source and inspiration of PP for Paul Wong, because of his experience in poverty and adversities (Wong, 2016d). In his long and varied research over four decades, the leitmotif has been the same: How to overcome the dark side of life in order to be a fully functioning human being. Thus, PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011, 2019, 2020), also known as existential positive psychology, has always been his approach to PP. Although he is mainly known for his research on meaning, he has made significant contributions to research, theory, assessment, and interventions across several domains.

Effective Coping with Frustration and Pain

In his first 10 years of research, Wong’s main interest was in persistence. Through a variety of intermittent reinforcement and punishment schedules, he was able to teach animals persistence and flexibility in overcoming prolonged frustration and pain (Wong, 1977, 1995). This line of research provided an animal model of the PP of optimism and persistence (Wong, 1979, 2006a). Wong’s research on persistence has also led to Rosenbaum’s (1990) development of learned resourcefulness in human beings. These research findings provide the empirical basis for his deep-and-wide hypothesis of negative emotions (Wong, 2012a, Wong & Worth, 2017)).

Effective Coping with Stress, Aging, and Dying

Wong’s main contribution to stress and coping research is the resource-congruence model (Wong, 1993; Wong, Reker, & Peacock, 2006) and the Stress Appraisal Measure (Peacock & Wong, 1990). Wong also made the case that effective coping needs to be a part of PP 2.0, because stress is an ever present reality in human existence (Wong, Wong, & Scott, 2006).

In the area of positive aging and dying, Wong’s main contribution was to reorient successful aging from biological factors to psychological and spiritual factors (Reker & Wong, 1988, 2012; Wong, 1989; Wong & Watt, 1991). Wong and associates developed the Death Attitude Profile-Revised, which includes three kinds of death acceptance as positive ways to face death (Wong, Reker, & Gesser, 1994).

Wong’s demonstration of spontaneous attribution, both causal and existential (Wong, 1991; Wong & Weiner, 1981), contributes to the understanding of meaning making. As well, Wong discovered that internal and external control function as two separate dimensions rather than two opposite poles on the same continuum (Wong & Sproule, 1984). Thus, positive and negative emotions and experiences can also be conceptualized as two separate interactive dimensions, which led to the dialectical framework of PP2.0 (Wong, 2009b, 2011b, 2016a).

Contribution to Assessments

In addition to those mentioned above, Wong has developed the following instruments, which can be used for both research and therapy: Personal Meaning Profile (Wong, 1998) and Personal Meaning Profile-Brief (McDonald, Wong, & Gingras, 2012); Trent Attribution Profile (Wong & Sproule, 1984); Coping Schemas Inventory (Wong, Reker, & Peacock, 2006); Meaning Mindset Measure (Wong, 2012b); Self-Transcendence Measure (Wong, 2016e); Life Orientation Scale (Wong, 2014); and Life Attitude Scale (Wong, 2009c).

Contribution to International Psychology

His contribution to international psychology is threefold: (1) his emphasis on the importance of cross-cultural perspectives in stress and coping and PP (Leong & Wong, 2003; Wong, 2013b; Wong & Ujimoto, 1998; Wong & Wong, 2006); (2) his organization of the International Biennial Meaning Conferences since 2000 (www.meaning.ca/conference), which have been attended by psychologists from over 30 countries; and (3) his research on death acceptance and the meaning of life, which has influenced Taiwan’s Life and Death Education (S. Chang, 2016) and the development of a meaning-oriented positive education (S. Chang, 2016; Wong, 2013c).

Contribution to Existential Competencies and Meaning Therapy

Aware of the prevalence of existential concerns (Frankl, 1985; Yalom, 1980), Wong (2016f) advocated the need to develop existential competencies in all mental health workers, regardless of their therapeutic modalities.

Wong’s (2010, 2015) meaning therapy represents a comprehensive approach to transforming existential anxieties to positive motivation and strategies for healing and flourishing. The main existential competences include the dual-systems model (Wong, 2012a), meaning-mindset (Wong, 2012b), and self-transcendence (Wong, 2016b). Meaning therapy is also known as existential positive interventions (Wong, 2016c). In sum, Wong is a positive psychologist shaped by humanistic and existential concerns.

Veronika Huta

Veronika Huta earned her Ph.D. in clinical psychology from McGill University, but chose to pursue research in eudaimonia. The main reason for choosing Huta over other more established positive psychologists in Canada in this chapter is to include a rising star whose research program shows promise of becoming an important part of PP 2.0 (Huta, 2016a).

Her eudaimonia research focuses on the existential-spiritual aspect of the human condition and emphasizes the active cultivation of virtue, not just the identification of signature character strengths. She is also exceptionally strong when it comes to theoretical integration, and has been working to contribute to the theoretical foundation for the eudaimonic-hedonic distinction (Huta, 2016b).

Huta (2015, 2016b, c) is mostly known for her comprehensive and systematic research on eudaimonic versus hedonic orientations. Based on a review of the literature (Huta & Waterman, 2014), she has distilled the definition to a combination of four elements: (1) pursuing virtue and excellence, (2) meaning and big picture thinking, (3) authenticity and self-honesty, and (4) growth and maturation.

When studying well-being outcomes, from the beginning she has included a more comprehensive package than mere subjective well-being—one which includes the more complex, more existential aspects of experience: meaning (feelings of significance, value, broad implications, personal resonance, and purpose), elevating experience (awe, inspiration, moral elevation, and transcendence or sense of connection with a greater whole), and self-connectedness, all of which have proven to relate more strongly to eudaimonic than hedonic pursuits (Huta, 2016d; Huta & Ryan, 2010). Her research on the eudaimonic orientation is another demonstration of the advantages of the person-centered holistic approach to PP.

She has also developed the most comprehensive measure of eudaimonic and hedonic orientations, called the HEMA (Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motives for Activities) scale. The original (Huta & Ryan, 2010) had nine items, and it was later updated to a 10-item version to include all four elements of her definition (Huta, 2016b). Research with the HEMA scale has shown that eudaimonic pursuits are associated with more positive contributions to others, society, and the environment, and more abstract thinking and future time perspective, thus consistent with the lifestyle characterized by self-transcendence (Huta, 2016b, e; Wong, 2016b).

Huta’s latest research with her student Braaten on worldviews (Braaten & Huta, 2016) is an even clearer indication that she has extended eudaimonic research to a metaphysical level of spirituality and meaning. Like Emmons, their research also demonstrates that worldviews matter. Human beings are not just creatures motivated by the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain, as proposed by those embracing a naturalist hedonic worldview, but spiritual beings struggling for meaning and purpose and exploring the moral and ethical implications of their actions and goals.

Braaten and Huta have developed (and continue refining) the most comprehensive measure of worldviews to date, based on Koltko-Rivera’s (2004) extensive literature review. They have empirically demonstrated the importance of worldviews for meaning and well-being. They have also shown that people are more likely to pursue eudaimonia—serving a greater purpose, achieving excellence in virtue and competence, fulfilling one’s unique potentials, and being true to oneself—when they embrace the existential belief that the universe and people exist for a greater purpose. Thus, two different lines of research—the search for meaning (Wong, 2012c, 2014) and the pursuit of eudaimonia (Huta, 2016a, b)—conducted independently have arrived at basically the same conclusion, adding credence to the meaning hypothesis of human flourishing.

Future of Positive Psychology in North America

Given the vibrant recent developments of PP in North American and globally, we are confident that PP will stay for the long haul as a sub-discipline of psychology, just like abnormal psychology (Wong, 2011b). From the perspective of PP 2.0, the future of PP represents the development of the new science of investigating how to bring out the best in people and society in spite of the dark side of human existence through dialectical principles. Here are some specific trends for the future.

Future Trends of PP in North America

From Hedonic to Eudaimonic Happiness

The happiness craze associated with the smiley face of PP 1.0 is over (Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2015). We foresee more research on eudaimonic happiness along the lines of research by Ryan (self-determination), Ryff (psychological well-being), Huta (eudaimonic well-being), and Wong (meaning and self-transcendence).

From Mindfulness to Self-Transcendence

We also do not believe that mindfulness will be the new panacea for PP, as many have suggested (Harris, 2008; Weiss & Hickman, n.d.; Williams & Penman, 2012). Although gaining peace of mind through the secular approach to the Buddhist practice of mindful meditation is helpful, it has limited benefits if it does not involve any change in core beliefs, worldviews, and way of life (Wong, 2006b). We hasten to add that Buddhism’s emphasis on no-self is only one of the several pathways to attain inner peace and self-transcendence (Wong, 2016a, b). For example, Wong (2012b) emphasizes the meaning-mindset, which will enable us to see life as potentially meaningful. He also stresses the motivation to pursue self-transcendence, which will reorient us from self-interest to caring for others in a responsible way (Wong, 2016b).

From American-Centered Approach to Indigenous Emphasis

Numerous psychologists have argued that PP is rooted in specific cultural contexts (E. Chang, Downey, Hirsch, & Lin, 2016; Kim, Yang, & Hwang, 2006; Leong & Wong, 2003; Wong, 2013b). Each ethnic/cultural group may have their own moral visions, which “inform people about what is worthy, good, and desirable, and about what constitutes the good, virtue, morality, health, and well-being” (Christopher, Wendt, Marecek, & Goodman, 2014, p. 5).

We foresee the development of indigenous PP for Chinese people (Wong, 2016a), aboriginal communities (McCormick & Wong, 2006), African Americans (Caldwell-Colbert, Parks, & Eshun, 2009), and Latina/o students (Vela, Lu, Lenz, & Hinojosa, 2015). We also encourage research on well-being and life satisfaction that is sensitive to cultural factors (Diener & Suh, 2000; Ujimoto, Nishio, Wong, & Lam, 1993; Wong & Ujimoto, 1998). Such research has a twofold objective: (a) discovering what is unique about each indigenous culture and (b) discovering what is universal or what is human nature.

From Lab Research to Real Life Experiences

The main problem with lab research is that it may not have external validity and may not be relevant to real life situations. The second limitation of lab research is that all kinds of painful human conditions cannot be studied in the lab due to ethical concerns. Therefore, for PP 2.0 research, it is essential to study real life situations. Csikszentmihalyi’s technique of sampling subjective experiences in real life is a promising approach. Biographical and historical research provides yet another fertile ground to study topics of PP 2.0.

Another argument in favor of this change in methodology is the need to honor the subjective experiences of research participants. Rating scores of well-being and meaning in life are difficult to interpret unless we know the mental state or life circumstances of participants while completing the rating scores (Wong, 2017 ). Therefore, future research based on self-reports needs to have at least a sub-sample that reports what is going through their mind while completing the self-ratings.

From Single-Minded Focus on Positive Variables to Dialectic Interactions

PP’s contribution to well-being will be limited if we continue to demonstrate empirically what we all know experientially, such as how being close to nature, listening to music, engaging in interesting activities, or being together with family and friends makes us happy. Such a pedestrian approach to documenting an endless list of activities that can make us happy without knowing the underlying conditions or cultural differences will not advance the science of PP.

It is a more challenging scientific task to investigate how positive variables interact with negative life circumstances to increase our well-being, character strengths, or group harmony, simply because there is very little research on dual-system interactions (Wong, 2012a) and we also have less personal experience in regards to dialectical outcomes.

Major Obstacles that May Prevent Positive Psychology from Growing

We can readily identify the following obstacles to future growth.

Commercialization of Positive Psychology

In the long run, the commercialization of PP beyond scientific support will weaken its credibility. We can understand why such a market is necessary because increasing numbers of positive coaches need to make a living, but, eventually, it could bring discredit to the entire field of PP (Wong & Roy, 2018).

Non-Collaboration Between Different Groups

The lack of willingness to collaborate between the PP and humanistic communities has hindered both groups from realizing their full potentials. One way to overcome this divide is to do quantitative research on humanistic constructs (e.g., Proctor, Tweed, & Morris, 2016) or to make full use of the mixed methodology (Wong, 2017). Another approach is to forge a closer tie between these two traditions by bringing them together in collaborative projects, such as the INPM’s International Biennial Meaning Conferences (www.meaning.ca/conference). Finally, a humble approach to science and a noble purpose for the greater good will facilitate collaboration between diverse groups.

Disparity Between Haves and Have-Nots

Overall, PP has catered to those who have the time and money to pursue happiness projects or benefit from positive coaches. It is hoped that PP 2.0 will develop interventions to help the homeless (Tweed, Biswas-Diener, & Lehman, 2012) and the hopeless (Wong, 2009c; Wong & McDonald, 2002), and equip people with better coping skills to grow and to become better persons through adversities (Wong, Wong, & Scott, 2006). Furthermore, PP has a responsibility to address the issue of poverty (Biswas-Diener & Patterson, 2011) and social injustice (Eidelson, Lyubansky, & Malley-Morrison, 2014).

Changes Needed to Increase Impact of PP

From the perspective of PP 2.0, the following things need to be achieved:

- We need to get across the message that PP is not just for people in neutral or positive territories, but also for the suffering masses (Wong, 2007, 2011b, 2019, 2020). It is a branch of psychology designed to bring out the best angels in our nature as a way of overcoming the dark side of life and human nature. Simply focusing on character strengths by itself is not enough, if we do not confront the evils of oppression, exploitation, and violence. It should focus on the new science of happiness and wellbeing through the gates of suffering.

- We need to give PP away to the community as Wong has done for many years (Wong, 2012d). We need to adopt a grassroots approach to educate people on the principles of meaningful living (Wong, 2016g) as a way to prevent mental illness and promote human flourishing. When more people have acquired the basic principles of meaning and practiced them, they will be able to live more positive lives and create a better society.

- We need to develop an alternative approach to positive education—positive education 2.0—as advocated by Wong (2013d) and S. Chang (2016). In a way that is different from the first wave of positive education, which emphasizes the science of happiness and signature strengths (Seligman, Ernst, Gillham, Reivich, & Linkins, 2009), positive education 2.0 seeks to cultivate a sense of personal and social responsibility (Linley & Maltby, 2009); affirm the inherent value, meaning, and dignity of individual life (Frankl, 1985); and emphasize the practical wisdom of living well (Schwartz & Sharpe, 2010) in light of the brevity of life. In Taiwan, this kind of positive education is called “life education”; it has become a national policy for all levels of public schools to include life education as part of their academic curriculum (S. Chang, 2016; Huang, Wang, & Lin, 2011). Thus, positive education 2.0 not only teaches students important life skills and moral values, but also imparts in students a sense of civic virtue and social responsibility necessary for a robust democracy.

- We need to secure funding for research based on a humble and holistic approach to science (Templeton, 1998) to carry out systematic research within the framework of PP 2.0.

Different from most PP assessment tools, which are based on short and simple self-reports of undefined psychological constructs (for a critique, see Wong & Roy, in press), Ryff’s well-being scale is multidimensional and lengthy; the long form of the scale consists of 84 questions and the medium form 54 questions (Seifert, 2005). This scale is much longer than the typical PP measure, yet it has been translated to more than 30 different languages and generated more than 500 publications because of its theoretical rootedness and universal appeal.

Consistent with Aristotle (1908) and existential positive human functioning (Frankl, 1985; Wong, 2009a), Ryff emphasized “know thyself and become what you are” as the key to her eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being (Ryff & Singer, 2008). Ryff also provided biological correlates (cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, immune) of a eudaimonic well-being that is rich in meaning and purpose, quality relationships, and continued growth (Ryff, 2012; Ryff & Singer, 1998).

Holistic Multidisciplinary Approach to Human Resilience. Another theme in Ryff’s research has been human resilience—the human capacity to maintain or regain well-being in the face of cumulative adversity and underlying neurobiology. Her holistic multidimensional research integrates several levels of analysis: sociodemographic characteristics, psychosocial resources, life stresses, health behaviors and practices, neurobiological risk and protective factors, and health outcomes with extensive psychosocial and biomarker assessments (Ryff, 2014b).

The main findings from longitudinal studies of aging have shown that those who remain purposefully engaged with life experience numerous health benefits. Such findings demonstrate the importance of promoting eudaimonic well-being and resilience across a broad segment of the population, including the socioeconomically disadvantaged and those suffering from cancer and child abuse (Ryff, 2014a, 2016; Ruini & Ryff, 2016).

Cross-Cultural Sensitivity. Since 1995, Ryff and her team have researched factors that influence health and well-being from middle age through old age via a study called MIDUS (Mid-Life in the U.S. National Study of Americans). She has also been involved in a parallel study in Japan. She has directly compared well-being, resilience, and adult development in Japan and the U.S. (Ryff et al., 2015). Thus, her third major contribution to PP is that she is keenly aware that well-being is rooted in culture, and hence interventions need to be sensitive to cultural contexts (Ryff et al., 2014). For example, she and her associates (Curhan et al., 2014) discovered that Japanese people were less affected by negative emotions than their American counterparts. This difference can be easily understood in terms of yin and yang differences in coping. Eastern cultures are more attuned to the tragedies and hardships of life and have learned to cope with patience and endurance—the yin aspects of adaptation and are less likely to expect to immediately eradicate every life problem (Lin, 1935; Tweed, White, & Lehman, 2002).

Ryff stands out as a model researcher on well-being and has avoided the many mistakes of American PP (Wong & Roy, in press). The above three areas of her contributions to PP happen to be among the defining characteristics of existential PP (Wong, 2009a) and PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011c). That is why she was introduced as the “Mother of PP 2.0” at the 2016 International Meaning Conference when she was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Robert A. Emmons

Robert Emmons is a Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Davis and the founding editor-in-chief of The Journal of Positive Psychology. He is the world’s leading scientific expert on gratitude (Emmons, 2007, 2013). However, to him, gratitude is more than just a valid instrument to enhance happiness, because “gratitude heals, energizes, and transforms lives” (Emmons, 2016) and the nature of gratitude is spiritual (Emmons, 2010; Emmons & Hill, 2001). The PP literature often ignores Emmons’s major contributions to spirituality and meaning. In this chapter, we want to highlight these larger contributions that pave the way for PP 2.0.

Spiritual Beliefs and Strivings Hold the Key to Well-Being. Like Viktor Frankl (1985), Emmons recognizes that spirituality is a core dimension of being human. Thus, people are viewed as bio-psycho-social-spiritual beings rather than mere animals. This high and noble view of who we are should fundamentally influence PP research regarding how we should live our lives. This deeper understanding of human nature elevates the academic discourse from the simple empirical question of what exercises may enhance well-being and happiness to the fundamental theoretical question of how to be becoming fully functioning human beings with spiritual strivings.

Consistent with humanistic-existential thinking, Emmons (2005) emphasizes the vital role of religion and spirituality in human existence by “establishing goals and value systems that potentially pertain to all aspects of a person’s life” (p. 731). By framing religion and spirituality in terms of goal-directed behavior, he makes a compelling case that meaning is not a matter of subjective feeling or thinking, but a matter of goal-directed actions towards ultimate concerns (Emmons, 1986, 1999).

Ultimate concerns are “concerns over ultimate questions of meaning and existence, purpose and values” (Emmons, 2005, p. 737), which express themselves in personal goals. These spiritual goals are characterized by striving to transcend the self and serving something greater than the self, by seeking a relationship with a higher power, and by integrating the individual with “larger and more complex units” (Emmons, 2005, p. 736); these characteristic are highly similar to Wong’s conceptualization of self-transcendence (Wong, 2016b).

Emmons’ meaning-centered approach to personality and well-being is evident in his definition of self-identity in terms of the “pursuit of personally significant goals in general, and goals of a religious and spiritual nature in particular” (Emmons, 2005, p. 732). His research has demonstrated that people with spiritual goals “tend to experience their lives as worthwhile, unified and meaningful” (Emmons, 1999, p. 104).

Finally, consistent with PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011c), Emmons has recognized that implicit worldviews and values systems—which give rise to spiritual strivings—are essential not only to human flourishing, but also to resilience in coping with adversity and traumas. For instance, Emmons’ (2005) research with persons with neuromuscular disease showed that when their strivings were centered on the sacred, “they [were] likely to experience life as fulfilling, meaningful, and purposeful, even in the face of a deteriorating and disabling physical condition” (p. 742).

Gratitude is an Expression of Spirituality. Gratitude is a natural expression of a spiritual life—a life that is fully aware of God or a Higher Power as the source of life and all its blessings. When gratitude is employed as an instrument to enhance personal happiness, such as paying a gratitude visit or writing a gratitude letter, it does not always work because it depends on each individual’s personal and cultural context (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013). Furthermore, a life focused merely on pursuing happiness whether through gratitude or other means, can undermine the very happiness that is being sought (Martin, 2008). However, when gratitude is cultivated as a spiritual practice, it works in every culture, because it has been an ancient spiritual discipline practiced in every religion. The simplest form of such practice is to count our blessings on a daily basis, not just for being alive, but also for the many benefits we have received (Wong, 2016c).

Emmons (2010) was especially correct in pointing out that the nature of gratitude has two components:

(1) It’s an affirmation of goodness. We affirm that there are good things in the world, gifts and benefits we’ve received. … (2) We recognize the sources of this goodness as being outside of ourselves. … I think true gratitude involves a humble dependence on others: We acknowledge that other people—or even higher powers, if you’re of a spiritual mindset—gave us many gifts, big and small, to help us achieve the goodness in our lives. (para. 9-10).

Contributions to PP 2.0. Emmons (2005) is fully aware that “what contributes to the self-perceived well-being of an individual might be detrimental to the well-being of others” (p. 742). Thus, a truly meaningful and fulfilling life is not just about the individual, but also about others and future generations. Emmons is also cognizant that spiritual striving towards the sacred may entail guilt and shame, but “dissatisfaction can be desirable if it is used as fuel for constructive life change. Even usually positive characteristics can have harmful consequences” (p. 742).

Finally, in agreement with Viktor Frankl (1985), Emmons (2005) believes that direct pursuit of happiness can be counterproductive, because “research indicates that happiness is often a by-product of participating in worthwhile projects and activities that do not have as their primary focus the attainment of happiness” (p. 733).

When we consider the totality of Emmons’ research on spirituality and meaning, we would agree that gratitude is not just an instrument to enhance happiness, but an overflow of a heart full of thanksgiving for the blessings of serving something greater than oneself. A great deal is owed to Emmons’ research and insights for the development of PP 2.0 (Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2015; Wong, 2011c). Like Carol Ryff, he is an important researcher responsible for the transition from PP “as usual” to PP 2.0.

Notable Positive Psychologists in Canada

Canada is not short of positive psychologists influential in research and/or teaching. Tayyab Rashid (www.tayyabrashid.com) is well known for his research on positive psychotherapy (Rashid & Howes, 2016). Robert J. Vallerand (www.lrcs.uqam.ca/rjvaller_en.htm), Professor and the Director of the Research Laboratory on Social Behavior at the Université du Québec à Montréal, is known for his research on the psychology of passion (Vallerand, 2015). Chris Davis of Carlton University is known for his research on meaning-making in tragic situations (Davis, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Larson, 1998). Another major player in meaning research is Gary Reker (Reker, Peacock, & Wong, 1987). Finally, Kenneth Hart is known for being the first Canadian professor to develop a university course on PP (Hart & Sasso, 2011).

However, we decided to focus on Paul Wong for his influence on the PP 2.0 movement and Veronika Huta for her systematic study on eudaimonic happiness, because of their potential impact on the future of PP in Canada.

Paul T. P. Wong

Suffering is both the source and inspiration of PP for Paul Wong, because of his experience in poverty and adversities (Wong, 2016d). In his long and varied research over four decades, the leitmotif has been the same: How to overcome the dark side of life in order to be a fully functioning human being. Thus, PP 2.0 has always been his approach to PP. Although he is mainly known for his research on meaning, he has made significant contributions to research, theory, assessment, and interventions across several domains.

Effective Coping with Frustration and Pain. In his first 10 years of research, Wong’s main interest was in persistence. Through a variety of intermittent reinforcement and punishment schedules, he was able to teach animals persistence and flexibility in overcoming prolonged frustration and pain (Wong, 1977, 1995). This line of research provided an animal model of the PP of optimism and persistence (Wong, 1979, 2006a). Wong’s research on persistence has also led to Rosenbaum’s (1990) development of learned resourcefulness in human beings. These research findings provide the empirical basis for his deep-and-wide hypothesis of negative emotions (Wong, 2012a, in press-a).

Effective Coping with Stress, Aging, and Dying. Wong’s main contribution to stress and coping research is the resource-congruence model (Wong, 1993; Wong, Reker, & Peacock, 2006) and the Stress Appraisal Measure (Peacock & Wong, 1990). Wong also made the case that effective coping needs to be a part of PP 2.0 (Wong, Wong, & Scott, 2006).

In the area of positive aging and dying, Wong’s main contribution was to reorient successful aging from biological factors to psychological and spiritual factors (Reker & Wong, 1988, 2012; Wong, 1989; Wong & Watt, 1991). Wong and associates developed the Death Attitude Profile-Revised, which includes three kinds of death acceptance as positive ways to face death (Wong, Reker, & Gesser, 1994).

Wong’s demonstration of spontaneous attribution, both causal and existential (Wong, 1991; Wong & Weiner, 1981), contributes to the understanding of meaning making. As well, Wong discovered that internal and external control are two separate dimensions rather than two opposite poles on the same continuum (Wong & Sproule, 1984). Thus, positive and negative emotions and experiences can also be conceptualized as two separate interactive dimensions, which led to the dialectical framework of PP2.0 (Wong, 2009b, 2011c, 2016a).

Contribution to Assessments. In addition to those mentioned above, Wong has developed the following instruments, which can be used for both research and therapy: Personal Meaning Profile (Wong, 1998a) and Personal Meaning Profile-Brief (McDonald, Wong, & Gingras, 2012); Trent Attribution Profile (Wong & Sproule, 1984); Coping Schemas Inventory (Wong, Reker, & Peacock, 2006); Meaning Mindset Measure (Wong, 2012b); Self-Transcendence Measure (Wong, 2016e); Life Orientation Scale (Wong, 2014); and Life Attitude Scale (Wong, 2009c).

Contribution to International Psychology. His contribution to international psychology is threefold: (1) his emphasis on the importance of cross-cultural perspectives in stress and coping and PP (Leong & Wong, 2003; Wong, 2013b; Wong & Ujimoto, 1998; Wong & Wong, 2006); (2) his organization of the International Biennial Meaning Conferences since 2000 (www.meaning.ca/conference), which have been attended by psychologists from over 30 countries; and (3) his research on death acceptance and the meaning of life, which has influenced Taiwan’s Life and Death Education (S. Chang, 2016) and the development of a meaning-oriented positive education (S. Chang, 2016; Wong, 2013c), and which was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award in Life Education by the National Taipei University of Nursing and Health.

Contribution to Existential Competencies and Meaning Therapy. Aware of the prevalence of existential concerns (Frankl, 1985; Yalom, 1980), Wong (2016f) advocated the need to develop existential competencies in all mental health workers, regardless of their therapeutic modalities.

Wong’s (2010, 2015) meaning therapy represents a comprehensive approach to transforming existential anxieties to positive motivation and strategies for healing and flourishing. The main existential competences include the dual-systems model (Wong, 2012a), meaning-mindset (Wong, 2012b), and self-transcendence (Wong, 2016b). Meaning therapy is also known as existential positive interventions (Wong, 2016c). Wong’s book, entitled Human Quest for Meaning (Wong, 2012c), also succeeded in bringing together an impressive list of international scholars who contributed a number of accessible chapters explicating of the role of meaning in research and therapy.

In sum, Wong is a positive psychologist shaped by humanistic and existential concerns, because of his own suffering.

Veronika Huta

Veronika Huta earned her Ph.D. in clinical psychology from McGill University, but chose to pursue research in eudaimonia. The main reason for choosing Huta over other more established positive psychologists in Canada in this chapter is to include a rising star whose research program shows promise of becoming an important part of PP 2.0 (Huta, 2016a).

Her eudaimonia research focuses on the existential-spiritual aspect of the human condition and emphasizes the active cultivation of virtue, not just the identification of signature character strengths. She is also exceptionally strong when it comes to theoretical integration, and has been working to contribute to the theoretical foundation for the eudaimonic-hedonic distinction (Huta, 2016b).

Huta (2015, 2016b, c) is mostly known for her comprehensive and systematic research on eudaimonic versus hedonic orientations, which represent differences in meanings, values, priorities, motives, ideals, and goals that guide the person’s chosen behaviors. In her definition of eudaimonia, she does not shy away from including virtue and meaning as explicit components. Based on a review of the literature (Huta & Waterman, 2014), she has distilled the definition to a combination of four elements: (1) pursuing virtue and excellence, (2) meaning and big picture thinking, (3) authenticity and self-honesty, and (4) growth and maturation.

When studying well-being outcomes, from the beginning she has included a more comprehensive package than subjective well-being, one which includes the higher, more complex, more existential aspects of experience: meaning (feelings of significance, value, broad implications, personal resonance, and purpose), elevating experience (awe, inspiration, moral elevation, and transcendence or sense of connection with a greater whole), and self-connectedness, all of which have proven to relate more strongly to eudaimonic than hedonic pursuits (Huta, 2016d; Huta & Ryan, 2010). Her research on the eudaimonic orientation is another demonstration of the advantages of the person-centered holistic approach to PP.

She has also developed the most comprehensive measure of eudaimonic and hedonic orientations, called the HEMA (Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motives for Activities) scale. The original (Huta & Ryan, 2010) had nine items, and it was later updated to a 10-item version to include all four elements of her definition (Huta, 2016b). Research with the HEMA scale has shown that eudaimonic pursuits are associated with more positive contributions to others, society, and the environment, and more abstract thinking and future time perspective, thus consistent with the lifestyle characterized by self-transcendence (Huta, 2016b, e; Wong, 2016b).

Wong and Roy (in press) have argued that ultimately a componential approach of emphasizing thinking, feeling, and behavior will not advance PP without a comprehensive theory about human nature and the individual as a holistic unity. Therefore, they have advocated PP 2.0 by emphasizing the humanistic values or noble aspects of human nature, such as the meaning mindset as a spiritually-oriented worldview (Frankl, 1985; Wong, 2011c) and the primary motivation of pursuing self-transcendence as the end value. We have always maintained that eudaimonic well-being results from such worldview and value (Wong, 2014, 2016b).

Huta’s latest research with her student Braaten on worldviews (Braaten & Huta, 2016) is an even clearer indication that she has extended eudaimonic research to a metaphysical level of spirituality and meaning. Their research supports our contention that worldviews matter. Human beings are not just creatures motivated by the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain, as proposed by those embracing a naturalist hedonic worldview, but spiritual beings struggling for meaning and purpose and exploring the moral and ethical implications of their actions and goals.