Introduction

This chapter focuses on the notion of good work from a meaning-centered approach (MCA). MCA views good work at three levels: the individual, the organization, and society. At the individual level, good work means that employees are empowered through intrinsic motivation to make the optimal use of their strengths, resulting in a high level of job satisfaction and productivity. At the organizational level, a virtuous servant style of leadership (Wong, 2004) unleashes the full potential of employees and provides a positive culture (Wong, 2005). At the societal level, good organizations assume their social responsibilities to contribute to the greater good beyond the bottom line. Thus, a good organization is not only a good place to work for, but also an agent of positive social change.

MCA, which is informed by existential positive psychology (EPP; Wong, 2010), is an example of an emergent branch of scholarship labeled as PP “2.0” (Wong, 2011), also referred to as the “second wave” of positive psychology (Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2015; Lomas & Ivtzan, 2015). When positive psychology (PP) first emerged in 1998, in what we could refer to as its “first wave” incarnation, its stated prerogative was to explore “positive” aspects of human functioning (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). This was in apparent contrast to “psychology as usual,” which was characterized as taking a deficit-based approach to human beings. However, as valuable as this emphasis on positive functioning was, critics suggested that this focus on positivity could potentially be problematic, in various ways. For instance, positioning ostensibly positive qualities (e.g., optimism) as desirable, and

At the heart of PP 2.0 is a focus on the centrality of meaning to human flourishing (Wong, 2011; Wong, 2012a). This is especially the case with MCA, which originates from the application of Frankl’s (1985) logotherapy paradigm to organizations. MCA has several advantages over alternative models, such as positivity, character strengths, or virtuousness, because it is capable of incorporating all these major themes of PP without the problems associated with the first wave of PP. Consistent with existential philosophy, MCA embraces human beings in their entirety, with their potentials for both goodness and “evil.” (While evil could be regarded as a somewhat metaphysically loaded term [Allison, 2002], it is used here to vividly capture the range of hateful and destructive acts that people are capable of undertaking). In practice, MCA allows individuals greater openness and readiness for positive change within the organization (Burger, Crous, & Roodt, 2008).

A Critical Review of PP and its Approach to Organizations

The first wave of PP could be characterized as the scientific study of positive emotions, positive traits, and positive institutions (Seligman & Csikszentmilahlyi, 2000). Applied

However, while PP has attracted enormous interest and enthusiasm, it has not been without its critics. For instance, Wong (2007a, 2007b) argued that the field’s emphasis on “happiness-oriented” outcomes like subjective well-being rendered PP guilty of encouraging people to pursue a futile hedonic quest instead of helping people to seek a

As a result of these types of criticisms, scholars within PP are more alert to the risks of simply focusing on the “positive,” and are engaging more critically with the very notions of positive and negative. With these developments, the field could be said to be moving into a “second wave” phase, labeled here as PP 2.0. In this, while there is still a focus on topics such as happiness, there is also a recognition of the potential challenges that are involved in such a pursuit. Moreover, from a dialectical perspective, it is seen that these challenges may actually be an integral part of eudaimonic happiness, where negative emotions, for example, could be part of the experience of happiness. While this might sound paradoxical (how could happiness and negative emotions go hand in hand?), if we shift from the understanding of happiness as simply a positive emotion, into the more complex understanding of it as a fulfilling way of being, negative emotions become an important dimension of happiness. When embraced and accepted, negative emotions can be a powerful catalyst

From the perspective of PP 2.0, Wong (2012a) has proposed the “deep-and-wide” hypothesis to highlight the positive benefits of negative emotions, thus complementing Fredrickson’s (2001) broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. According to Wong (1995, 2006), frustration and other negative experiences can motivate us to dig deeper into our inner resources and expand our horizons for new possibilities. For example, research on possible benefits of negative affect show improved memory performance, reduced judgmental errors, improved motivation, and increased effectiveness of interpersonal strategies (Forgas, 2013; Storbeck & Clore, 2005). There are indeed numerous empirical findings based on the dialectical notion of flourishing arising from the integration and transcendence of negative and positive. From Wong’s own research alone, these include the benefits of death acceptance (Wong & Tomer, 2011), transformative coping (Wong, Reker, & Peacock, 2006), and tragic optimism (Wong, 2009). Similarly, Cozzolino’s (2006) research on death awareness and acceptance shows that when individuals are exposed to the personal realization of their death, their reaction tends to be intrinsic and growth orientated. These studies indicate that direct experience with death enhances intrinsic life changes, such as renewed appreciation for life, concern for others, and higher levels of meaning.

Perhaps because first wave PP has tended toward a rather binary and restricted notion of happiness (one centered around ostensibly “positive” topics, as explored above), applications of PP to the workplace have been similarly limited. For instance, Ko and Donaldson (2011) conducted an extensive review of the literature in PP in relation to

An Existential Paradigm Shift

According to Kuhn (1962), a paradigm shift occurs when there are enough problems that question the basic assumptions of a dominant conceptual framework. The first wave of PP represented a paradigm shift from the deficit model of “psychology as usual,” with its preoccupation with disorder and dysfunction, to a focus on happiness and strengths, driven by a recognition that the deficit model failed to adequately cover human potentialities (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Similarly, the more recent shift to a second wave paradigm has been prompted by the recognition that “first wave” PP tended to overlook the “dialectical” nature of flourishing, including a focus on inescapable existential aspects of human existence and the central role of meaning in surviving and thriving. It acknowledges that the world is full of hardships and yet full of meaning potentials (Frankl, 1985). When we discover the hidden opportunities for meaningful engagement and act with responsibility and ethics, we will find our lives more fulfilling.

The important insight of PP 2.0 – and indeed of EPP (Wong, 2010), as PP 2.0 is thoroughly existential in character – is that suffering is both inevitable and potentially beneficial; it is through engaging with painful situations that we dig deeper into ourselves and become open to new possibilities which will enrich our lives, as per Wong’s (2012b) “deep-and-wide” hypothesis. PP 2.0 also addresses the fundamental paradoxes and dilemmas of human existence. For instance, here is one of the fundamental paradoxes of human nature: Whenever we draw attention to ourselves, be it making ourselves happier or more virtuous, we end up defeating our own purpose. Whenever we direct our attention to others, be it helping others or contributing to society, we end up both happy and virtuous. This paradox is rooted in human nature, just as Viktor Frankl (1988) has said: “Self-transcendence is the essence of existence. Being human is directed to something other than itself” (p. 50).

There are encouraging signs that positive organizational psychology is beginning to take on board this existential perspective. For example, the latest publication of Positive Psychology in Practice edited by Joseph (2015) includes Bretton’s (2015) chapter on the existential dimensions of PP, and Pauwels’ (2015) chapter on the uneasy but necessary role of negativity in PP. The fact that this chapter on MCA is part of the present volume is another indication. In sum, PP 2.0 – and MCA, which is emblematic of this second wave paradigm – is meaning-oriented rather than happiness-oriented in pursuing the good life. Informed by existential psychology and philosophy, it recognizes the dark side of the human condition as well as the bright side of fulfilling human potentials. It is based on both scientific findings and time-tested wisdom on healing and flourishing.

MCA to Positive Organizations

Since a large part of adult life is work, it follows that research findings on the benefits of meaning in life are most likely applicable to work life. We have found that meaning is the foundation for well-being (Hicks & Routledge, 2013; Park, Park, & Peterson, 2010; Ryff & Keyes, 1995) and psychosocial adaptation (Reker & Wong, 2012). However, so far, this natural connection between work and meaning in life has not been widely recognized. The meaning hypothesis posits that when we value and pursue what really matters and what is intrinsically worthwhile, we will experience authentic happiness. Meaning is not only inherently virtuous and

MCA is based on the application of Frankl’s logotherapy (1985) to the workplace. MCA believes that every person is unique and has intrinsic value, but it also recognizes the dark side of human nature – greed, pride, prejudice, egotistic tendency, and the potential for destructive acts. MCA benefits from the increasing interest in integrating positive psychology with existential psychology, as per PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011). Meaning as a major source of intrinsic motivation both inspires and energizes workers (Thomas, 2000), particularly if one’s career is regarded as a “calling” (Wrzesniewski, McCauley, Rozin, & Schwartz, 1997), and good work as an achievement of excellence and ethics (Gardner, Csikszentmihalyi, & Damon, 2001). MCA capitalizes on the innate human capacity for

The PURE Way to Flourishing

PURE stands for Purpose, Understanding, Responsibility, and Enjoyment, and serves both as a complete definition of meaning and as a conceptual framework for implementing MCA in the context of work.

The Imperative of Purpose

A sense of purpose within an organization can be assessed on five key dimensions, and

Thus, in practical terms, purpose can be assessed using Table 14.1, in which each of the seven dimensions of organizational functioning can be rated from 1 to 10 on the five key dimensions of purpose. The total score, aggregated from all 70 individual scores on the matrix, reflects the strength and scope of the organization’s purposefulness. We can predict that the higher the score, the greater the morale and productivity.

| Absent or present? | Clear? | Compelling? | Consistent? | Collaborative? | |

| 1. Vision/mission | |||||

| 2. Societal concerns | |||||

| 3. Organization | |||||

| 4. Human resources | |||||

| 5. Service/product | |||||

| 6. Efficiency | |||||

| 7. Quality |

Table 14.1 Assessment of different levels of purpose in five dimensions across seven areas of organizational functioning.

Bridges of Understanding

Understanding is the key to assessing the real situation in order to find solutions to an organizational problem. Facing up to the challenge requires that we understand and accept the seriousness of an existing problem. Understanding also involves making sense of what happens and knowing oneself. Having a sense of coherence and a clear concept of self-identity are essential for meaningful employment and optimal functioning. All kinds of barriers can prevent effective teamwork and slow down the production process. These gulfs can come from cultural differences, miscommunication, personal biases, and the built-in walls in a highly hierarchical organization. Territorial instincts, tribal mentalities, and power struggles can further cripple an organization. No organization can survive and flourish without building bridges of understanding that connect people.

The Power of Responsible Action

Responsibility has always been considered as an important area in leadership and management (Bass & Bass, 2008). More recently, Cameron (2011) defines responsible leadership as virtuous leadership. Responsible action will include making the right decision, hiring the right people, developing the right product, and eliminating wasteful practices. Sometimes, it takes courage to do restructuring and retooling in order to survive turbulent times. Recent years have seen an emerging literature on the value of responsible leadership, not only to the success of organizations themselves (see, e.g., Berger, Choi, & Kim,

Enjoyment

Enjoying refers to the intrinsic and deep satisfaction from both active

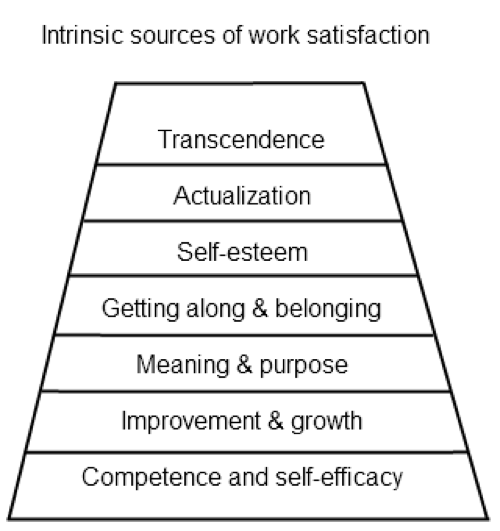

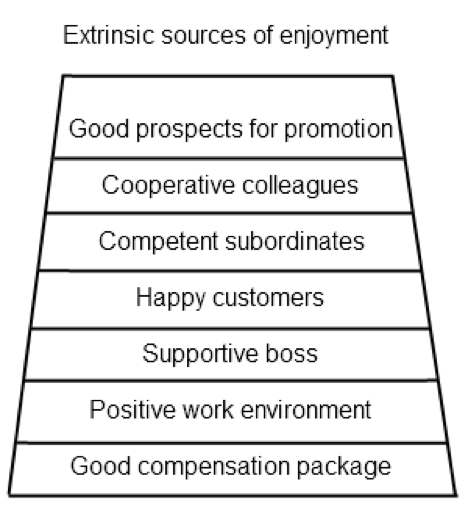

The PURE model predicts that both extrinsic and intrinsic sources of satisfaction are important for well-being and productivity. However, at both the low end and high end of salary scales, intrinsic motivation becomes most important. Figure 14.1 and Figure 14.2 describe both intrinsic and extrinsic sources of work satisfaction at the workplace. We could give a score of 1 to 10 for each level of intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction. These scores provide important information about areas for continuous improvement. A low level of enjoyment is sufficient ground for

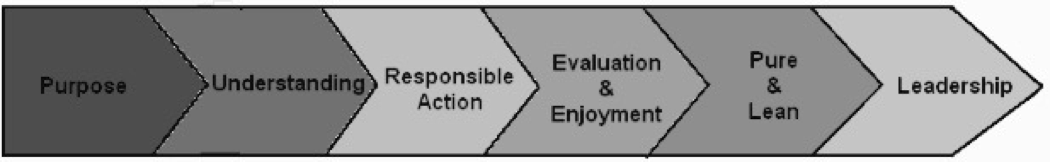

Applications of the PURE Strategy

The four components of PURE can be taught through workshops, modeling, and coaching. They can also be measured qualitatively and quantitatively. More importantly, the benefits of MCA can be measured by increased profit, productivity, and morale as well as decreased waste and absenteeism. Figure 14.3 shows how the PURE model moves an organization forward in good times and bad. As mentioned earlier, leadership is a key to organizational excellence. Effective leaders set the standard of competence and integrity. Effective leaders are also able to inspire and motivate others, and develop the right strategies to move the company forward (Griffin & Hu, 2013).

Figure 14.3 The PURE way to move forward.

Positive Corporate Culture

MCA entails creating a positive culture because of its emphasis on human resources development and meaning at work. Schein (1990) defines corporate culture as “the unique and essential function of management” (p. 317). Organizations need a positive culture in order to keep their best workers, motivate their workforce, and grow their business. When you walk into a positive and successful organization, you can feel the difference the moment you step inside the door. The atmosphere is inviting, and there is a distinct sense of dedication and energy about the people working there. Ultimately, a positive cooperative culture is essential for sustainable growth. MCA has been applied to transforming culture (Wong, 2002, 2005; Wong & Gupta, 2004), restoring integrity (Wong, 2002, 2004), and improving teamwork and cooperation (Wong, 2005, 2006). It would be difficult to transform a corporate culture without a leadership totally committed to positive change.

Wong and Gupta (2004) identify four types of positive cultures: (1) progressive–adaptive culture, (2) purpose-driven culture, (3) community-oriented culture, and (4) people-centered culture. The above cultures contribute to intrinsically motivated high performance, because they meet people’s deepest needs for meaning, community, spirituality, and agency. The ideal company should possess the attributes of all four types of healthy corporate cultures. Wong and Gupta (2004) also identify five negative cultures: (1) authoritarian–hierarchical culture, (2) competing–conflictive culture, (3) laissez-faire culture, (4) dishonest–corrupt culture, and (5) rigid–traditional culture. The above five negative cultures are not mutually exclusive. Negative cultures can be transformed through MCA. But the most urgent task is to weed out toxic elements and transform negative cultures through the PURE strategy.

The PURE Way to Reduce Wasteful Spending

The fastest ship will not go very far if there is a leak in the hull. The PURE model not only improves the speed, but also repairs the leakage. A systematic implementation of the PURE strategy will greatly reduce toxic elements, such as nepotism, cronyism, fraud, and mismanagement, while increasing efficiency, productivity, innovation, and job satisfaction. The PURE model provides a strategic and systematic way to reduce waste in financial and human resources in connection with the pruning of toxic elements. Here is a brief guideline of a meaningful way of cutting costs.

Firstly, every organizational department could be asked to come up with a clear mission statement. The purpose assessment tool (Table 14.1) can be used to prioritize the purpose, objectives, and projects of each operational unit. Anything not essential to the stated mission would warrant closer scrutiny. Of course, no organization can survive on purpose alone; a sound business model is also essential. Thus, both purposefulness and profitability need to be included in the equation. The challenge is to develop a workable formula to reduce waste and enhance productivity of each unit. This formula will yield a Value Index involving appropriate weightings of Mission Value and Financial Value. Some departments may load heavily in Mission Value because of its contribution to the mission and purpose of the organization, but contribute little financially. The reverse may be true for some other departments. Any unit with an overall negative Value Index does not deserve to exist.

The second step is to consult and communicate with all stakeholders to ensure that everyone in the organization understands the need to cut spending and the due process of reducing waste. It will take negotiation and compromise to develop fair, transparent procedures to eliminate non-essential operational processes and potentially reduce the contribution of non-productive members. The third step is that all levels of the organization, from the CEO to the most junior employees, take personal responsibility to ensure that due process is being carried out fairly and effectively. Great care is taken so that people who may face a reduction in their working hours or even lose their job entirely will be fairly compensated and given the opportunity for career counseling and assistance to secure another job. Finally, the benefits of reducing waste and reviving a struggling organization will be enjoyed by all stakeholders. More importantly, the result of reducing wasteful spending may have a positive rippling effect on society. In developing this type of positive culture, in which a model like PURE can flourish, effective leadership is needed. One such model of good leadership in this regard is that of servant leadership, as the next section explores.

Servant Leadership

Servant leadership is an ideal model for implementing MCA generally, and the PURE approach specifically, because it emphasizes such qualities as integrity, humility, serving a higher purpose, fulfilling a mission, and the need to develop and release the creative potential of all workers. Servant leadership is of ultimate importance in the PURE way of organizational transformation (Wong, 2004). The leader sets the tone and provides a role model. Only the leader can ensure that the PURE principles are being implemented systematically at all levels of the organization.

Servant leadership emphasizes such qualities as integrity, humility, virtue, higher purpose, responsibility and the need to develop the potentials of all workers. In terms of the identification and assessment of the construct of servant leadership, Wong and colleagues have developed two relevant instruments: a self-assessment of servant leadership (Page & Wong, 2000); and the 360-degree assessment of leadership (Rude, 2004). From a more practical perspective, Page (2009) has provided a detailed hands-on guide to transforming management to servant leadership. In terms of empirical validation of the concept, Searle and Barbuto (2010) reported that servant leadership could impact organizational virtuousness at all three levels of good work and increase productivity.

In sum, the PURE way is humane and virtuous. PURE provides a conceptual framework and procedures to eliminate waste and toxic elements, and build up the full potentials of both individuals and the organization. Before looking at future directions for research and implementation of the PURE model, we shall examine a case study of organizational excellence that fully embodies this approach.

A Case Study in Organizational Excellence

Synovus Financial Corporation (www.synovus.com), listed as one of the best companies to work for by Fortune magazine for many years, is a good example of the benefits of MCA and servant leadership. Synovus employees find meaning and satisfaction through serving customers, fulfilling their potentials, and working under caring servant-leaders. The PURE principles are clearly at work throughout this organization.

Synovus’ culture of “people first” is a key to its success. The value inherited from the early pioneers of the company and forged down through the years remains unchanged. It emphasizes the imperative of treating each worker, stakeholder, and customer with kindness and respect because every person matters. Such unwavering commitment to serving others generates stability, loyalty and enduring success.

Its relationship-based philosophy dictates its values and defines its future. Its culture of service over self is clearly reflected in its customer covenant. The same philosophy is also applied to each team member. It wants each employee to feel that they have an opportunity to contribute, to grow and to benefit from the company’s success. It aspires to “become the employer of choice in every market we serve. Creating a great workplace is the foundation of every Synovus strategy. Team member enthusiasm yields higher productivity and profitability” (Page, 2000, p. 1).

It does not take much stretch of imagination to understand why servant leadership is the best model for a corporation devoted to serving others. “I am convinced,” writes William Turner, as chairman of the Executive Committee of Synovus Financial Corporation, “that servant leadership will be the way to manage in the future, not only because it brings personal fulfillment to everyone in the organization, including the boss, but also because it can deal with change quickly and effectively” (Turner, 2000). “The vision must have meaning,” Turner continues, “because man cannot live without meaning. The vision must be holistic and congruent, encompassing the church, the family, the community, and the institution. If it doesn’t, values and priorities will conflict” (p. 83).

Given Synovus’ meaning-centered vision, one can readily detect the PURE principles in their policies and operations. The purpose of serving customers with enthusiasm and excellence is so ingrained in all workers that it has become a habitual practice. Likewise, the company’s interest in the professional and personal growth of its team members has led to a variety of career development programs. The focus on facilitating individual development and coaching for optimum performance further enhances the meaning of work, because employees feel that they are able to grow and fulfill their potential within the organization.

In addition to taking care of its customers and employees, Synovus is also unabashedly dedicated to the higher purpose of improving the quality of life in the communities it serves. Community service is entrenched as an integral part of the company. In 1996, it formally codified its community outreach projects under an umbrella effort called REACH: Recognizing and Encouraging an Atmosphere of Community and of Hope. REACH encourages and enables team members to give back to the communities. “The creation of the foundations [for community service] was the beginning of servant-leadership in our company,” writes Turner (2000), “I believe a servant leader should meet the needs of the people who work with him – at work, at home, and in the community” (p. 139).

It is hard not to value the principles of serving when the culture of the heart permeates everything the company does, from the top management to each and every employee. All the policies and decisions convey the same message of “people first.” Explicit understanding of the values and purpose of Synovus is reinforced by its customer covenant which reads in part:

We pledge to serve every customer with the highest levels of sincerity, fairness, courtesy, respect and gratitude, delivered with unparalleled responsiveness, expertise, efficiency and accuracy. We are in the business to create lasting relationships, and we will treat our customers like we want to be treated.

The consistent message is to treat people right, to do the right thing, and to give your best in everything you do. There is no exception, no excuse. The ethos of Synovus is conducive to responsible actions. When the work is intrinsically motivating and meaningful, people are more likely to be engaged and passionate about what they do.

The philosophy of serving the community rather than maximizing short-term financial gains empowers Synovus to do what is right and what is in the best interest of the customers and communities. It should be noted that this is not at the expense of sound financial analysis: it are constantly improving its policies and procedures of risk management to reduce bad loans, and it also makes sure that it builds up sufficient capital asset in order to be prepared for the unexpected. By being proactive, it is able to protect its customers against future losses. Synovus thus provides an example of how one can create a positive and virtuous company by following the PURE principles and servant leadership.

Future Research

MCA is a case of value-centered and virtuous leadership. It offers a promising framework for positive management research with the dialectical framework of PP 2.0. However, more research is needed on how best to promote meaning at work, given that Gallup-Heatherways’ (2015) State of Global Well-Being report also indicates that 52% of all adults are struggling in purpose-related well-being, and these people are consequently less likely to be engaged in their jobs. This high rate of disengagement may be due to a variety of reasons, such as work stress, emotional disorders, mismatch between the individual and work, or a lack of meaning. Schawbel’s (2015) recent observation that “millennials” are the least engaged generation suggests that they may have difficulty finding jobs that meet their high expectations for meaningful work; thus, how to increase engagement through meaningful work remains a research challenge (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). Similarly, from an assessment perspective, while there are already valid and reliable measures of general meaning in life (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006; Wong, 2012b) and meaning in work (Steger, Dik, & Duffy, 2012), future research needs to further elucidate the substantive content of meaning in life (McDonald, Wong, & Gingras, 2012; C. Peterson & Park, 2014; Wong, 1998). Likewise, there is a need for quantitative and qualitative meaning-centered audits with respect to a sense of meaning at work.

From a critical perspective, we also need research on the potential downsides and risks of promoting meaning at work; for instance, PP 2.0 also directs our attention to the potential abuse of power by leaders. Passion and talents could be used by some ambitious individuals to manipulate and con stakeholders for personal gain; similarly, even too much of character strengths, such as confidence and optimism, could become vices (Chang & Sanna, 2003). MCA may shed new light on the role of personality factors in organizations. Likewise, it is possible that management may use dedication to mission as a way to exploit employees; leaders may justify their unkind treatment of others in the name of serving a higher purpose (McGregor et al., 1998; J. B. Peterson, 2012). PP 2.0 also provides a fertile ground for research on how to integrate both the positive and negative in creating an optimal organization. More research should be directed to increasing intrinsic motivation while reducing waste. Similarly, we need to find ways to reduce/remove toxic elements and, at the same time, transform negative emotions and experiences into positive motivation.

Conclusions

This chapter defines good work as work that is beneficial at three levels: individual, organization, and society. It then critiques the limitations of the first wave of PP and positive organization research, primarily because it generally fails to engage with the darker side of the human condition. Consequently, it argues for a paradigm shift to the existentially-toned PP 2.0 as an ideal synthesis between the thesis of “psychology as usual” (which did pay attention to this darker side) and its antithesis, the strength-based approach of “first wave” PP (such integration will greatly expand the scope of PP 2.0 research and applications).

The chapter then introduced the meaning-centered approach (MCA) to positive management and organizational excellence, and in particular the PURE approach to organizational functioning. MCA provides a deeper and richer understanding of work because it is informed by existential psychology regarding the reality of human existence. MCA incorporates management processes with servant leadership as practical ways to reduce waste and at the same time enhance virtuousness, creativity, and productivity. This chapter also introduces practical guidelines on how to implement servant leadership and capitalize on our innate capacity for meaning making.

Since no existing method has succeeded in completely liberating us from human foibles and baser aspirations, MCA represents a promising and workable framework to keep these destructive forces in check, while cultivating personal responsibility for good work and higher aspiration. The most attractive aspect of MCA is that it does not require exceptional virtue and talents; it only requires a shift in attitude and motivation from self-centeredness to self-transcendence. With an appreciative attitude, even mundane or low-paying work can become meaningful. In sum, MCA not only provides a healthy relationship with the dark side of the human condition, but also empowers us to achieve human excellence and create good work to the benefit of all stakeholders.

References

- Allison, H. E. (2002). On the very idea of a propensity to evil. The Journal of Value Inquiry, 36(2), 337–348.

- Arnold, K., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E., & McKee, M. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 193–203.

- Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Berger, R., Choi, C., & Kim, J. (2011). Responsible leadership for multinational enterprises in bottom of pyramid countries: The knowledge of local managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(4), 553–561.

- Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13, 119.

- Bretton, R. (2015). The existential dimensions of positive psychology. In S. Joseph (Ed.), Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education and everyday life (2nd ed.; pp. 47–60). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Burger, D. H., Crous, F., & Roodt, G. (2008). Logo-OD: The application of logotherapy as an organization development intervention. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 34(3), 68–80.

- Cameron, K. (2011). Responsible leadership as virtuous leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 25–35.

- Cartwright, S., & Holmes, N. (2006). The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Human Resource Management Review, 16(2), 199–208.

- Chang, E. C., & Sanna, L. J. (Eds.) (2003). Virtue, vice, and personality: The complexity of behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Cooperative, The (2012). Ethical Consumer Markets Report 2012. London, UK: Author.

- Cozzolino, P. J. (2006). Death contemplation, growth, and defense: Converging evidence of dual-existential systems? Psychological Inquiry, 17(4), 278–287.

- Donaldson, S. I. (2011). Determining what works, if anything, in applied positive psychology. In S. I. Donaldson, M. Csikszentmihalyi, & J. Nakamura (Eds.), Applied positive psychology: Improving everyday life, health, schools, work, and society (pp. 3–11). London, UK: Routledge.

- Forgas, J. P. (2013). Don’t worry, be sad! On the cognitive, motivational and interpersonal benefits of negative mood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 225–232.

- Frankl, V. (1985). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

- Frankl, V. (1988). The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of logotherapy. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

- Gallup-Healthways (2015, October 14). Gallup-Healthways state of global well-being final report. Retrieved from http://info.healthways.com/hs-fs/hub/162029/file-1634508606-pdf/WBI2013/Gallup-Healthways_State_of_Global_Well-Being_vFINAL.pdf?t=1427897436886Page

- Gardner, H., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Damon, W. (2001). Good work: How excellence and ethics meet. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Gruber, J., Mauss, I. B., & Tamir, M. (2011). A dark side of happiness? How, when, and why happiness is not always good. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(3), 222–233.

- Held, B. S. (2002). The tyranny of the positive attitude in America: Observation and speculation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(9), 965–991.

- Held, B. S. (2004). The negative side of positive psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44(1), 9–46.

- Hicks, J. A., & Routledge, C. (Eds.) (2013). The experience of meaning in life: Classical perspectives, emerging themes, and controversies. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Hitlin, S. (2007). Doing good, feeling good: Values and the self’s moral center. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(4), 249a–259.

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. London, UK: Routledge.

- Joseph, S. (Ed.). (2015). Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education and everyday life (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Kamdron, T. (2005). Work motivation and job satisfaction of Estonian higher officials. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(13/14), 1211–1240.

- Ko, I., & Donaldson, S. I. (2011). Applied positive organizational psychology: The state of the science and practice. In S. I. Donaldson, M. Csikszentmihalyi, & J. Nakamura (Eds.) Applied positive psychology: Improving everyday life, health, schools, work, and society (pp. 137–154). London, UK: Routledge.

- Kuhn, T. (1962). The Structure of scientific revolutions (50th anniversary ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lomas, T., & Ivtzan, I. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Exploring the positive-negative dialectics of wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9668-y

- Mauss, I. B., Tamir, M., Anderson, C. L., & Savino, N. S. (2011). Can seeking happiness make people unhappy? Paradoxical effects of valuing happiness. Emotion, 11, 807–815.

- McDonald, M. J., Wong, P. T. P., & Gingras, D. T. (2012). Meaning-in-life measures and development of a brief version of the Personal Meaning Profile. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 357-382). New York, NY: Routledge.

- McGregor, H. A., Lieberman, J. D., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Arndt, J., Simon, L., & Pyszczynski, T. (1998). Terror management and aggression: Evidence that mortality salience motivates aggression against worldview-threatening others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 590–605.

- McNulty, J. K., & Fincham, F. D. (2011). Beyond positive psychology? Toward a contextual view of psychological process and well-being. American Psychologist, 67(2), 101–110.

- Nord, W. R., Brief, A. P., Atieh, J. M., & Doherty, E. M. (1990). Studying meanings of work: The case of work values. In A. Brief, & W. Nord (Eds.), Meanings of occupational work: A collection of essays (pp. 99-100). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Page, D. (2000). Finding meaning through servant leadership in the workplace. Paper presented at the International Conference on Searching for Meaning in the New Millennium, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

- Page, D. (2009). Servant empowered leadership: A hands-on guide to transforming you and your organization. Langley, Canada: Power to Change.

- Page, D., & Wong, P. T. P. (2000). A conceptual framework for measuring servant leadership. In S. Adjibolooso (Ed.), The human factor in shaping the course of history and development (pp. 69-110). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Park, N., Park, M., & Peterson, C. (2010). When is the search for meaning related to life satisfaction? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2(1), 1–13.

- Pauwels, B. G. (2015). The uneasy – and necessary – role of negative in positive psychology. In S. Joseph (Ed.), Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education and everyday life (2nd ed.; pp. 807–822). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Peterson, C., & Park, N. (2014). Meaning and positive psychology. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 5, 2–8.

- Peterson, J. B., (2012). The meaning of meaning. In P. T. P. Wong, L. C. J. Wong, M. J. McDonald, & D. W. Klaassen (Eds.), The positive psychology of meaning and spirituality. (pp. 11–32). Birmingham, AL: Purpose Research.

- Reker, G. T., & Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Personal meaning in life and psychosocial adaptation in the later years. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 433-456). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rude, W. (2004). The connection between servant leadership and job burnout. Unpublished master’s thesis, Trinity Western University, Langley, Canada.

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. I. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727.

- Schawbel, D. (2015, October 14). The 4 things millennials want most from employers may surprise you. Business Insider. Retrieved from: http://www.businessinsider.com/what-millennials-want-most-from-employers-2015-4

- Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Searle, T. P. & Barbuto, J. E. (2010). Servant leadership, hope, and organizational virtuousness: A framework exploring positive micro and macro behaviors and performance impact. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. doi:10.1177/1548051810383863

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

- Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well‐being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice‐friendly meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487.

- Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20, 322–337.

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93.

- Storbeck, J., & Clore, G. L. (2005). With sadness comes accuracy; with happiness, false memory. Psychological Science, 16(10), 785–791.

- Szekely, F., & Knirsch, M. (2005). Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility: Metrics for sustainable performance. European Management Journal, 23(6), 628–647.

- Turner, W. B. (2000). Learning of love: A journey toward servant leadership. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1995). A stage model of coping with frustrative stress. In R. Wong (Ed.), Biological perspectives on motivated activities (pp. 339-378). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2002). Creating a positive, meaningful work climate: A new challenge for management and leadership. In B. Pattanayak & V. Gupta (Eds.), Creating performing organizations: International perspectives for Indian management. New Delhi, India: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2004, Spring). The paradox of servant leadership. Leadership Link, 3-5. Ohio State University, Leadership Research Center.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2005). Creating a positive participatory climate: A meaning-centered counselling perspective. In S. Schuman (Ed.), The IAF Facilitation Handbook (pp. 171-190). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2006). Is your organization an obstacle course or a relay team? A meaning-centered approach to creating a collaborative culture. In S. Schuman (Ed.), Creating a culture of collaboration: The International Association of Facilitators handbook (pp. 229-256). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2007a). Positive psychology: A quiet revolution. In P. T. P. Wong, L. C. J. Wong, M. J. McDonald, & D. W. Klaassen (Eds.), The positive psychology of meaning and spirituality (pp. 17–27). Abbotsford, Canada: INPM Press.

- (2007). Perils and promises in the pursuit of happiness [Review of the book In search of happiness: Understanding an endangered state of mind]. PsycCRITIQUES, 52(49). doi:10.1037/a0010040

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). An existential vision of the good life: Toward an international psychology and psychotherapy based on meaning[Review of the book Existential psychology east-west] PsycCRITIQUES, 54(51). doi:10.1037/a0018290

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). What is existential positive psychology? International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 3(1), 1-10.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012a). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). What is the meaning mindset? International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 4(1), 1-3.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Gupta, V. (2004). The positive psychology of transformative organizations: A fresh perspective and evidence from the Anglo context. In V. Gupta (Ed.), Transformative organizations (pp. 341–360). New Delhi, India: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P., Reker, G. T., & Peacock, E. (2006). The resource-congruence model of coping and the development of the Coping Schema Inventory. In P. T. P. Wong, & L. C. J., Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 223-283). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Tomer, A. (2011). Beyond terror and denial: The positive psychology of death acceptance. Death Studies, 35(2), 99-106.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Weiner, B. (1981). When people ask “Why” questions and the heuristic of attributional search. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 650-663.

- Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C. R., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(1), 21–33.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., Ivtzan, I., & Lomas, T. (2017). Good work: A meaning-centred approach. In L. G. Oades, M. F. Steger, A. Delle Fave, & J. Passmore (Eds.), The

This publication was partially supported by the research grant on Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life from the John Templeton Foundation.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.