Abstract

This chapter describes the Meaningful Living Group as a community-based meaning-centered positive group intervention. This group work is informed by existential positive psychology (EPP; Wong, 2010a) and Positive Psychology 2.0 (PP2.0; Wong, 2011). More specifically, it consists of introducing 12 important principles of meaningful living in lay people’s terms to participants in the Meaningful Living Group.

Keywords: happiness, meaning, group, existential, logotherapy, mental health

Introduction

This chapter briefly reviews the meaning-enhancing group work in the past and focuses on the present author’s Meaningful Living Group as a promising approach to advancing positive mental health. The main premise is that meaning plays a vital role in happiness and well-being (Batthyany & Russo-Netzer, 2014; Wong, 2012a). Positive psychology (PP) research has concluded that a happy life is a meaningful life (Watkins, 2016). Furthermore, to fully understand meaning in life, we need to explore the big questions of existential positive psychology (EPP; Wong, 2010a) and embrace the dark side of human existence as called for by the second wave of positive psychology (PP2.0; Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2015; Wong, 2011). Meaning-centered positive group work has much to recommend itself for three reasons: (1) It is an effective way to give PP away (Wong, 2012b); (2) it is economic and can help many people at the same time; and (3) it is relevant to all people because it addresses universal existential concerns (Lukas, 1986/2014; Yalom, 1995). It represents an ideal marriage between PP and existential psychology (Wong, 2010a). According to Corey (2009), existential groups have the potential of helping participants be more honest with themselves, more open-minded in their perspectives, and more aware of what makes life meaningful. Such objectives can be beneficial to ordinary people. Logotherapy or meaning therapy, as a distinct school of existential therapy, is most relevant to PP and psychotherapy because it is unique in its optimistic outlook and emphasis on personal growth and spirituality (Frankl, 1986; Wong, 2014a). Most meaning-centered groups are based on logotherapy (Lantz, 1998) and designed to help individuals with addiction (Somov, 2007), cancer (Breitbart et al., 2015; Ebrahimi, Bahari, & Zare-Bahramabadi, 2014), depression (Robatmili et al., 2015) and clinical problems and personal growth (Dezelic & Ghanoum, 2015). There are a few examples of meaning-centered groups with non-clinical samples (Ghamari, 2013; Leontiev, 2015; Lukas, 2014).

Leontiev’s Life Enhancement Group Work

Leontiev’s (2015) life enhancement group work is intended for the non-clinical population. This group work represents a shift from the analysis of what is wrong to existential principles of how to grow psychologically; in other words, it is a move from therapy to coaching. It takes three full days to complete the group work. The focus is on understanding general existential principles and applying these principles to help participants think about their own long-term problems in a more adaptive way. The facilitating mental health professional does not directly teach these general principles but, through Socratic dialogue and group discussion, helps participants to induce or deduce them. The axiom of the group work is that everyone has some needs and strives towards fulfilling these needs. The main hypothesis is that many long-term problems occur because of people’s inability to process their life experiences of unmet needs in an adaptive manner. The assumptions are that they will be able to cope with their long-term problems, both solvable and unsolvable, once they achieve a deeper understanding of the world and their role in it.

Lukas’ Dereflection Groups

In contrast to Leontiev, who begins with participants sharing their long-term problems, Lukas (2014) discourages participants talking about their problems. She calls her group work “dereflection groups,” as her main focus is to redirect the members’ orientation away from their problems to positive and meaningful activities. The assumption is that such a reorientation is needed in order to achieve self-transcendence. Thus, her group work is positively-oriented and meaning-enhancing in terms of both objective and methodology. Consistent with Frankl’s (1986) logotherapy, Lukas (2014) argues that self-transcendence is the best possible positive intervention because it offers the following to her clients: (1) It broadens their values, (2) it opens the door for them to discover something worthy of self-transcendence, (3) it protects them from egocentricity, and (4) it enables them to find meaning directly, and happiness indirectly, in their pursuit of self-transcendence. At the core of Lukas’ meaning-centered group intervention is giving her clients “a picture of a human being that gives hope and courage” (p. 43). Lukas (2014) believes that the most effective way to bring about the greatest transformation in people is to begin with their basic existential assumptions and their natural capacity for spiritual understanding. Her reasoning is that if we are able to help our clients accept and embrace the noble view of a human being with a spiritual dimension, capable of creating a better and more meaningful future, we will do more good for them than merely teaching them coping skills or PP exercises. During dereflection group meetings, participants are discouraged from talking about their “unresolved problems and the depressing descriptions of [their] illnesses” (Lukas, 2014, p. 90). Instead, they are told to think about the pleasant aspects of their lives. They were encouraged to sharpen their perception of “positive moments” (Lukas, 2014, p. 91), which may include small joys in ordinary things, such as the budding of a potted plant or a pleasant memory from an old photo. One of the group participants introduced the practice of “a diary of beautiful things the day had brought” (Lukas, 2014, p. 93).

Wong’s Meaningful Living Group

Rather than leaving to the group members to bring up positive materials for group discussion, as in Lukas’ (2014) group, the present author gives a lecture before the group discussion that provides the content and conceptual tools for group members to learn important principles of meaningful living. In addition, different from all previous meaning-centered group work, the present author’s approach incorporates PP research findings as well as wisdom from both the East and the West beyond the traditional domains of existential psychology and logotherapy. Thus, it is a much broader approach. This section seeks to explain the principles of meaningful living in lay people’s language. In the first two lessons, the present author attempts to meet people at their level by not imposing any theoretical perspectives on them. He appeals to their common experiences, observations, and introduces some empirical findings to establish the important role of meaning in living a good life. The next two lessons provide the theoretical foundation of logotherapy as the basis for meaningful living. The remaining lessons focus on the important principles in meaning-centered existential positive interventions (Wong, 2010b, 2012c, Wong’s chapter in this volume). The main message is that it is never too late to become what one is meant to be—it begins with taking personal responsibility to make meaningful changes, one step at a time.

Methodology

The Meaningful Living Group meetings are first advertised on www.meetup.com and the present author’s www.inpm.org website. Each cycle consists of 12 sessions between an introduction session and a concluding celebration. The introduction familiarizes potential members with the objectives and methodology of the groups. The concluding session briefly wraps up, which is followed by a party where certificates of completion are given to individuals who have completed at least 10 out of the 12 sessions. These lessons were offered every other week free of charge. On average, there were 20 people in attendance over three cohorts. Two facilitators conducted the small group discussion after the lecture. The group discussion could last more than an hour, depending on the preferences of the group members, but never longer than one and a half hours. During orientation, potential participants are informed that the group is to be considered a guided journey to discover how to live a happy and meaningful life based on the science of PP and meaning therapy. Furthermore, they are told that there is more to life than being happy (Smith, 2013) and that meaning and purpose are necessary for living a good life (Wong, 2014b). Participants are then challenged with three basic questions about how to make life worth living:

- Everyone has only one life—how do you get it right the first time?

- Life is finite; life is short—how do you make the most of it?

- Everyone wants a better life—how do you achieve it?

Finally, participants are informed that through the lectures, group discussions, and take-home exercises, they can make progress in finding answers to these important questions. The introduction is concluded with an invitation to join the important journey of self-discovery and self-improvement.

Lesson 1: Who Am I?

Socrates’ famous quote, “Know Thyself,” is a philosophical and psychological imperative. It applies to every major area of psychology, from self-acceptance to self-esteem, from

The Importance of Self-Knowledge

Self-knowledge is the foundation for building a meaningful and fulfilling life. The journey of healing depends on recognizing our own brokenness and weaknesses; the pathway of flourishing depends on acknowledging our intrinsic value and strengths. Unfortunately, many people are afraid to find out the truth about themselves, especially in regard to their “dark side” with its problems. However, we are each unique and worthy human beings in spite of the things that we fear to face. In accepting ourselves, we will find liberation and empowerment. The negative consequences of not knowing your real

- Choosing the wrong career or mate,

- Acting inappropriately and encountering unnecessary frustration,

- Wandering in the wilderness and feeling lost,

- Going through life without feeling like you are living,

- Feeling uncomfortable in your own skin, and/or

- Experiencing mental health problems and relational issues.

The positive benefits of knowing your real

- Assuming personal responsibility,

- Discovering your true or authentic self,

- Creating your unique path and future,

- Finding your passion and your mission, and/or

- Living a life of purpose, productivity, and happiness.

Beware the Dangers of Self-Deception

Many people have some kind of self-deception, as most of the contents of our minds are unconscious. For instance, ego defense mechanisms are unconscious. Pride and fear are often the reasons for most of these unconscious contents (Jung, 1962). Very few people will dare to tell us the naked truth about our dark sides; even if they do, we won’t accept what they say unless we are ready and willing to face ourselves. Recognizing that our defense mechanisms and self-serving biases are universal tendencies will help us no longer insist on our own righteousness and begin to consider and understand other people’s points of view. Furthermore, understanding the duality of our personality will help us manage the negative aspects of ourselves in a way that serves the positive side.

Self-Acceptance as Pre-Condition for Positive Change and Personal Growth

The antidote of self-deception is self-acceptance. Self-acceptance enables us to honestly and realistically conduct self-assessment in order to make necessary changes. Self-acceptance means embracing yourself as you are, both your potentials and limitations. Inner pain often serves as a warning sign that something is wrong in your life and changes are urgently needed. In fact, a healthy self-concept depends on self-acceptance. Accepting one’s inherent value and worth as a human being provides an unshakable foundation for personal growth. This positive affirmation also includes acknowledging one’s capability of making positive changes and pursuing what really matters. This sense of self-worth and self-confidence comes when you face and accept yourself as you really are rather than as what you think other people expect you to be. True self-esteem does not depend on superficial characteristics, but on accepting your uniqueness and intrinsic value. You can make your life better when you become a better person, and the best way to be your best self is to improve from the inside out. Many people erroneously equate a better life and future with a better living standard, but the so-called “American Dream” has become a nightmare for many people. Have more money can improve our living conditions, but it does not necessarily lead to a meaningful and fulfilling life. Thus, I propose that each of us can live a better life by becoming a better person, regardless of our current conditions and life circumstances, if we continue on the journey of self-discovery and meaning-seeking.

Who Are You? What is Your True Self?

Your true self is bigger than your occupation, your performance, and even your problems. You have more potential than you realize, so do yourself a

How to Develop a Healthy Self-Concept

We will cover all these points in the future lessons:

- Belief in one’s inherent value and worth,

- Belief in one’s capacity for growth,

- Making constant self-improvement,

- Embracing both one’s strengths and weaknesses,

- Exercising one’s freedom and responsibility to pursue what really matters, and

- Engaging in relationships that matter.

Take-Home Message

Knowing yourself is the best investment you will ever make. Happy people know and accept themselves; they are attuned

Discussion Questions

- How would you answer the question “Who am I?”

- How would you answer the question “What kind of person do I want to become?”

- If money were not an issue, what would you want to do with your life?

- What would be the mission statement or motto of your life?

- What are you going to work on over the next few days to help you feel more comfortable being yourself?

Exercises

- Describe the “real you” in one sentence.

- Ask your best friend to describe the “real you” in one sentence.

- What kind of person do you want to be five years down the road?

- What might be some of your blind spots?

- What aspects of yourself do you have the most difficulty facing?

Resources

- Saul McLeod’s article on Carl Rogers (simplypsychology.org/carl-rogers.html)

- Clayton Christensen’s book, How Will You Measure Your Life?

- Rollo May’s book, Man’s Search for Himself

- George Vaillant’s book, Wisdom of the Ego

- Jordan Peterson’s TVO talk, “The Nature of Evil” (tvo.org/video/163167/big-ideas-jordan-peterson)

Lesson 2: What Really Matters in Life?

The next step of self-discovery is exploring your values and discovering what matters to you and makes your life worthwhile. Although your life goals may evolve over time, changing across different life stages, you always need a clear sense of purpose or direction in order to move forward. All of us only have one life which will soon pass away, but what is done for a higher purpose will last. If you have the right mindset and are willing to bring your best effort and creativity to your work, you can turn what is the most mundane into a sacred mission.

Three Big Lies

In order to do this, we first need to expose the following lies, which have been responsible for ruining many lives. There’s Nothing I Can Do. The first big lie is that you do not matter because you lack the right opportunities, intelligence, or abilities. You may see yourself as a victim to circumstance, fate, or karma, and may not believe that you are capable of making life better. Thus, you defeat yourself even before you try to do something positive. However, the truth is that every life has value and yours is no exception. Everyone has much to offer to society; everyone has much to achieve. Even if you think you do not possess a great intellect, a good education, or special talents, there is still so much you can do with your life by cultivating your human capacity for qualities such as compassion, love, and service. Life is About Being Happy. The second big lie is that you have to be happy in order to live a worthy life. Life is more than just about being happy. To live a life without frustration or fear is to live a life without growth. The common saying “No pain; no gain” also applies to you. Worse still, the mentality of pleasure-seeking may open one to all kinds of temptations and regrets. The pursuit of hedonism and self-illusion, without any regard for consequences, may lead to decadence and even the demise of civilization. All promises of hedonic happiness will eventually destroy you. If you just blindly pursue hedonic happiness as your primary life goal, you will be like a moth flying into a flame. Money Can Buy Everything. The third big lie is that you have to be rich in order to be somebody. This lie says you need to have money to enjoy life, gain respect, and do whatever you want. No wonder so many people have sold their souls in order to be rich. They betray their friends, step on other people, and resort to unethical means in order to get rich. No wonder the Bible says that the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil (1 Tim. 6:10). While wealth is a useful instrument that can advance the well-being of individuals and society, greed or the love of money can destroy many lives.

What Really Matters to You

On the other hand, there are two pillars to a meaningful life: self-transcendence and authenticity. Self-transcendence means living for a higher purpose or the greater good; the cornerstone of living a meaningful life is stepping out of ourselves and serving something or someone greater than us. Authenticity means being true to yourself and taking care of your own well-being holistically, as mentioned in the previous lesson. These two pillars are interdependent. You must be true to your calling and develop your full potential in order to give your best in serving others.

Self-Determination and Goal-Setting

We are born, we live, and then we die. However, while some live happy and productive lives, others waste away in misery. What makes the difference? You may be surprised to learn that it is not so much due to different circumstances as much as due to difference choices. More than anything else, the basic assumptions, worldviews, and core values we choose can determine how we spend our lives on earth. Our free will can either be our greatest blessing or our greatest curse. Our capacity for self-determination enables us to transcend any and all the determining forces in life. The biggest tragedy in life is people allowing their fears, society, or even parents dictate how they live their lives. You can start setting new goals right where you are at this moment. Think of the kind of projects you have always wanted to do. Select one that reflects your interests and values the most, such as reconciliation with your loved ones or going back to school to complete your education. It is important that you start engaging in an activity that has intrinsic value—worth doing in its own right—such as volunteering or learning a new skill or subject. The more intrinsic your core values, the less dependent you will be on contingencies or external circumstances. The more self-transcending your life goals are, the more meaningfulness you will experience.

Take-Home Message

What really matters in life is not money or fame, but active engagement in pursuing life goals according to our core values and calling.

Discussion Questions

- What would you love to do most, if you were free to pursue anything you want?

- What do you really care about? What matters to you?

- What are the things you are passionate about?

- What dreams did you cherish when you were young?

Exercises

- How much is your life worth? $1 million or more?

- Does the value of your life depend on your career or profession?

- When is the pursuit of meaning a more promising approach to achieving a worthy life than the pursuit of happiness or wealth?

Resources

- Kevin Anderson’s article, “Suffering and the Quest for Wisdom” (psychotherapynetworker.org/magazine/currentissue/item/2094-dark-passage)

- Chip Conley’s TED talk, “Measuring What Makes Life Worthwhile” (youtube.com/watch?v=UROCz70tlMY)

- Michael Steger’s TEDxCSU talk, “What Makes Life Meaningful” (youtube.com/watch?v=RLFVoEF2RI0)

- Marvin McDonald, Paul T. P. Wong, and Daniel Gingras’ chapter on the brief version of the Personal Meaning Profile (drpaulwong.com/documents/HQM2-chapter17.pdf)

Lesson 3: What is the Meaning-Mindset and its Benefits?

The Life Orientation Scale or Meaning-Mindset Measure

The present author has developed a Life Orientation Scale (LOS; Wong, 2012d) to measure the meaning-mindset. Here are several sample items:

- I can find something meaningful or significant in everyday events.

- No matter how painful the situation, life is still worth living.

- What really matters to me is pursuing a higher purpose or calling regardless of personal cost.

- I am willing to sacrifice personal interests for the greater good.

There is face validity that individuals who score high on the LOS are more likely to devote themselves to humanitarian relief work, social reform advocacy, religious work, or the life of an artist. One line of research is showing whether a high score on LOS is related to pursuing such vocations that require personal sacrifice. Another line is showing whether a high score on the LOS is related to various virtues such as altruism, compassion, and self-transcendence. One can also develop a simple behavioural test: Those who are willing to deny themselves small comforts, such a fasting for a day for a good cause or another person, are more likely to pursue and achieve great things that involve self-sacrifice. LOS predicates who will pass this behavioural test. The two orientations of the meaning-mindset and success-mindset exert pervasive influences on our lives and society, from career choices and character strengths to civic virtues and community development. It is difficult to develop a harmonious, compassionate, and virtuous society without a significant number of people subscribing to the meaning-mindset. In fact, the present author believes that a meaning-mindset is exactly what is needed to create a culture that values social responsibility and service to humanity. Ultimately, a meaning-mindset will result in a kinder and more harmonious society with more sustainable development than a success-mindset. I invite all mental health professionals to prove me wrong.

The Meaning-Mindset and the Spiritual Dimension

According to Frankl (1985), the meaning-mindset involves a shift of basic orientation from ego to logos. This shift of perspective enables us to see clearly the meaning advantages listed in the last lesson. We cannot see clearly the value of meaning and virtue if we are consumed by misguided ambitions for power, wealth, and fame; nor can we appreciate the joy of serving others if we are obsessed with pursuing physical pleasures and cheap thrills. Once we are spiritually awakened, we will begin to see things differently and perceive meaningful moments of beauty and goodness even in ordinary events, as Lukas (2014) has described. The activation and cultivation of a meaning-mindset involve affirmation of the intrinsic meaning and value of life as well as the human capacity of freedom of will—the will to pursue meaning and spirituality. In the next lessons, we will explain these foundational assumptions necessary for living a meaningful life in the face of suffering and death. Suffice to say that the entire meaning enterprise is based on the belief that we are spiritual beings. Our uniquely human capacities for meaning, self-transcendence, and self-determination are rooted in our spiritual nature. The meaning-mindset is simply the capstone of our spirituality. Spiritual activation plays a big part in shifting our attention from everyday busyness to meaningful living. There are three stages in spiritual activation: (1) exploring one’s core values and assumptions, as discussed in the last lesson; (2) awakening one’s insight into the benefits of meaning-orientation, as discussed in this lesson, and (3) implementing one’s insight, as will be discussed in the next lesson.

Take-Home Message

Perspective is everything. If we look at life with a meaning-mindset, all trivial concerns will fade away and we will be open to discover more meaning in our lives.

Discussion Questions

- Suppose you are allowed to take only three things with you to a distant place—what would they be? Why do these three things matter to you the most?

- What is something that matters more to you than happiness and success?

- What is the major difference between Frankl’s concept of the pursuit of meaning and the contemporary concept of the pursuit of success and growth?

Exercises

- Complete the Life Orientation Scale (LOS) (drpaulwong.com/documents/wong-scales/life-orentation-scale.pdf)

- Write a brief paragraph entitled, “This I Believe.” Describe what you believe to be most valuable and important in life.

Lesson 4: What is the Foundation for a Meaningful Life? Three Basic Tenets of Logotherapy

The genius of Viktor Frankl is that his logotherapy is directly linked to his deep understanding of the noble and spiritual aspect of human nature. Logotherapy or meaning therapy is effective to the extent it is able to help clients reorient themselves away from their egotistic concerns and assume their responsibility to pursue spiritual meaning, which is to serve someone or something beyond oneself (i.e., self-transcendence). In this lesson, we will focus on the three inter-connected basic tenets of logotherapy (Frankl, 1985, 1986): (1) the freedom of will, (2) the will to meaning, and (3) the meaning of life. One cannot just accept only one or two of these three tenets; they have to be embraced as an integrated package for a good reason as follows.

Freedom of Will

The freedom of will is not about being free to do or say whatever one wants. What Frankl has in mind is the radical spiritual freedom we have against all the deterministic forces of the environment, genes, and fate. Freedom of will is possible because of the human capacity for self-distancing: “By virtue of this capacity [people] are capable of detaching [themselves] not only from a situation but also from [themselves]” (Frankl, 1988, p.17). Such a capacity enables us to be free in all circumstances, for “everything can be taken from a [person] but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way” (Frankl, 1985, p. 86). Therefore, we always have the freedom to take a stand towards restrictive conditions and transcend our fate. Such freedom is also made possible by our capacity of self-transcendence—to transcend the constraints of time and space as well as our own inherent limitations and finiteness. We always have the freedom to make the right choices, no matter how oppressive the circumstances are. We can always exercise the freedom of will to say “Yes” to life. Frankl also differentiates between responsibility and responsibleness. The former comes from possessing the freedom of will. The later refers to exercising our freedom to make the right decisions in meeting the demands of each situation: “Existential analysis aims at nothing more and nothing less than leading [people] to consciousness of their responsibility” (Frankl, 1986, p. 275). To be able to transcend our situations and assume responsibility to do the right thing is the most liberating and empowering message. To all those who say that they cannot change their lives because of depression, poverty, or other limiting factors, we can always choose to adopt a positive attitude or make some small change that is under our control. The power of self-transcendence as a result of the exercise of the freedom of will can be summarized as follows, based on Lukas (1991/2015):

- Changing from blaming others for problems to assuming responsibility to find solutions.

- Switching from selfish pursuit (ego) to serving others or a worthy cause (logos).

- Getting motivated by the fulfillment of spiritual longings rather than immediate need gratification.

- Being willing to suffer and sacrifice for the greater good or a higher purpose.

- Being willing to let go of what cannot be changed and transcend unavoidable suffering and loss.

- Being open to the meaning potentials of every situations and life as a whole.

- Activating one’s spiritual dimension to discover what really matters.

Will to Meaning

Once we exercise our spiritual freedom of will, we will be able to make very different choices. We will be able to choose to pursue meaning and self-transcendence by doing what is right and responsible. The will to meaning is “the basic striving of [people] to find and fulfill meaning and purpose” (Frankl, 1988, p. 35). The will to meaning is possible because of the human capacity to transcend one’s immediate circumstances. Self-transcendence is essential for finding happiness, which is not the end, but the by-product of trying to forget oneself. “Only to the extent to which [people] fulfill a meaning out there in the world, do [those people] fulfill [themselves]” (Frankl, 1988, p. 38). The will to meaning represents a universal spiritual longing, a noble desire to be truly human. It provides an innate motive to serve a higher purpose and an innate sense of moral responsibility to do what is right. The implementation of self-transcendence represents the last stage of spiritual activation—doing something for the good of others out of a sense of ethical responsibility. This could be a small gesture of offering a cup of water to a thirsty person, or going out of one’s way to help a friend in need. Any practice of the will to meaning and self-transcendence will grant us a deep sense of satisfaction. The litmus test of meaning is not subjective feelings, but the objective criterion of making some sacrifice for the greater good. The more we exercise in this area, the more sensitive and responsive our will to meaning.

Meaning of Life

If oxygen is necessary for physical health, we have to assume that it is available everywhere on planet earth. Similarly, if meaning is necessary for our spiritual and mental health, we can assume that meaning is available everywhere in this world. Frankl (1985) makes a compelling case that meaning is even available in Nazi death camps. However, while meaning potentials are available in every situation, it is up to us to discover it. “According to logotherapy, we can discover this meaning in life in three different ways: (1) by creating a work or doing a deed; (2) by experiencing something or encountering someone; and (3) by the attitude we take towards unavoidable suffering” (Frankl, 1985, p. 133). Attitudinal values are especially important in situations of unavoidable suffering. Frankl (1988) claims, “This is why life never ceases to hold a meaning, for even a person who is deprived of both creative and experiential values is still challenged by a meaning to fulfill, that is, by the meaning inherent in the right, in an upright way of suffering” (p. 70). Creative values are available whenever we use our unique talents to do something creative and to add value to this world through our work, both paid and volunteer. Meaning can be experienced when we approach work with the right attitude of taking it as an opportunity to contribute to the common good or a higher purpose. Experiential values also come from having a positive attitude towards what life offers, whether it be an attitude of gratitude and appreciation or an attitude of savoring something good or learning something helpful. In other words, we can discover something beautiful and meaningful in ordinary situations provided we have a meaning-mindset. By making use of the meaning triangle of attitude, creativity, and experience, we can overcome both the tragic triad and the neurotic triad. The tragic triad consists of pain, guilt and death (Frankl, 1985). These negative experiences make us more aware of our needs for meaning and spiritual aspiration. Frankl (1985, 1986) has observed that people are willing to endure any suffering if they are convinced that this suffering has meaning. Thus, suffering without meaning leads to despair. The neurotic triad comprises depression, addiction, and aggression (Frankl, 1985). These emotional disorders stem from our feelings of meaninglessness or existential vacuum. Any attempts to increase a sense of meaning will help us transcend the neurotic and tragic triads.

Take-Home Message

The human capacities of freedom, responsibility, and the pursuit of meaning provide the foundation for meaningful living.

Discussion Questions

- Give a personal example of practicing the creative, experiential, or attitudinal values.

- Do you understand the paradox that we have to step out of ourselves in order to fulfill ourselves?

- What is holding you back from pursuing your dreams and ideals?

Exercises

- How would you encourage a friend who has lost his job and is in despair?

- If you believe that there is purpose in life and there is a reason for your existence, how would that make you more resilient?

- What kind of freedom can you have in very oppressive situations?

Lesson 5: What are the Sources and Ingredients of Meaning? The PURE Model

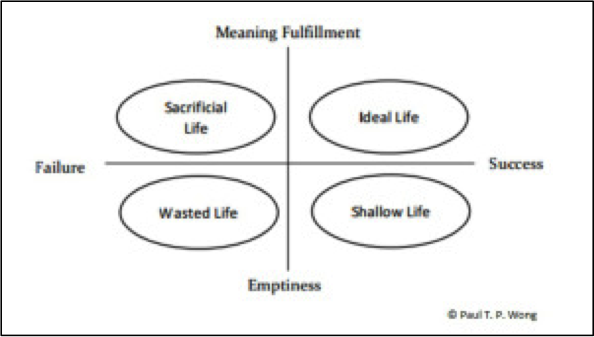

In a ground-breaking research on sources of meaning (Wong, 1998a), the present author asked hundreds of people from all walks of life what contributes to an ideal meaningful life, if money were not an essential. It was found that there are eight sources of meaning and the good life: achievement, acceptance, transcendence, intimacy, relationship, religion, fairness, and positive affect (emotions). It is understandable why relationships are rated as the most important. We are social beings; it is only normal that we will feel that life is empty and meaningless if we are isolated and without friends. Positive affect is also expected because scientific research has repeatedly demonstrated a close connection between meaning and happiness. What is most instructive in these findings is that society plays an important role. We feel that it is important that society provides fair treatment or equal opportunities. Another instructional aspect is the balanced nature of these sources of meaning, as seen in Figure 2 below. Achievement is balanced by the acceptance of our limitations, intimate relationships with family members and good friends are balanced by relationships with broader social circles, and self-transcendence or self-sacrifice is balanced by social justice and fairness. Balancing is an important exercise to avoid extremes and achieve the golden mean or middle way. It represents a humble and wise way of living the good life. Internal balance naturally leads to external harmony because one’s hubris or extreme ambition often leads to interpersonal conflict. Religion and spirituality offer an overarching global meaning for some people.

Figure 2. The balance between the sources of personal meaning, which leads to healing and flourishing.

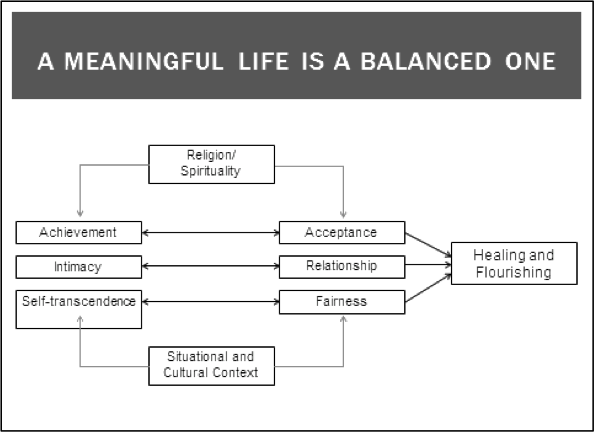

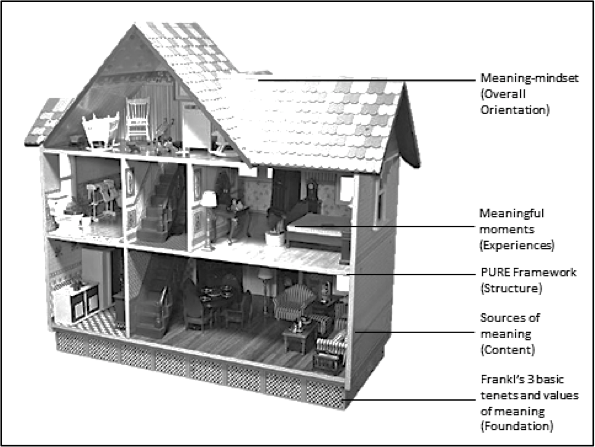

Wong’s PURE Model of Meaning

What are the basic components of meaning? Based on PP research on meaning (Batthyany & Russo-Netzer, 2014; Hicks & Routledge, 2013; Wong, 2012a), Wong has identified Purpose, Understanding, Responsibility, and Enjoyment/Evaluation or PURE as the constituents of meaning. Purpose refers to both the direction and priorities of one’s life. Understanding has to do with making sense not only of ourselves but also our role in the world. Responsibility reminds us that we are accountable to others and a higher authority. A clear sense of personal responsibility is a prerequisite for a civil society and ethical decisions. Finally, enjoyment/evaluation sums up the joy and self-regulation of a life well lived. Together, the PURE unit functions as the scaffold to build a better future for the self and society. The meaning research literature has provided ample support regarding the importance of purpose, understanding, responsibility, and positive emotions (please see Wong’s Positive Existential Therapy chapter in this volume for research support for these four components). The overall picture of a meaningful life can be represented in Figure 3 below. The image summarizes this and all the previous lessons. If your life is anything like what is depicted in this picture, you will enjoy happiness even in stormy days.

Figure 3. A metaphorical representation of a fully meaningful life.

Take-Home Message

Meaning means purpose, understanding, responsibility and enjoyment (PURE). We can achieve meaningfulness through a balanced approach in several key domains in life, such as relationships, achievement, acceptance, and self-transcendence.

Discussion Questions

- What are your core values? Where do they come from?

- How does your worldview (beliefs and assumptions about the world and people) affect your life?

- In what ways does meaning makes your life more enjoyable and your suffering more bearable?

Exercises

- Complete at least one of the three measurements of meaning below and indicate which area of your life is the most meaningful and which area is the least meaningful:

- Wong’s (2013) PURE test (org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/ Meaningful-Living-Project-Exercise-6-PUREtest.pdf)

- Wong’s (1998b) Personal Meaning Profile (PMP) (drpaulwong.com/documents/wong-scales/personal-meaning-profile.pdf)

- Steger, Frazier, Oishi, and Kaler’s (2006) “The Meaning in Life Questionnaire” (org/sites/default/files/images/stories/pdf/selfmeasures/PURPOSE_MEANING-MeaninginLife.pdf)

- Describe the one thing you have done in your life that is most meaningful to you.

- Examine your beliefs and reflect on which are not functional or adaptive and need modification.

- Ask yourself whether the assumption or belief that life has intrinsic meaning and value is functional or dysfunctional.

Lesson 6: How Do I Find Happiness in Difficult Times?

Everybody wants happiness. It is easy to be happy when everything goes your way and when your every dream is fulfilled. Unfortunately, for most people, life is not a smooth path, nor is it a joy ride. The challenge is how to find happiness in the midst of uncertainty and adversity. Lyubomirsky (2007) argues that 40% of our happiness is under our intentional control, regardless of circumstances and genes. She introduced several happiness-enhancing techniques, such as practicing gratitude, forgiveness, goal setting, and mindfulness. She has extended Seligman’s (2004) Authentic Happiness based on additional research findings. Other research in PP has also shown that happy people are more likely to be open to see the good in their lives (Fredrickson, 2001), have meaning in their lives (Emmons, 2003; Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006), and enjoy loving relationships (Peterson, 2013). Thus, our happiness depends not only on skills, but also on who we are—our mindset, meaningfulness, and relationships. In addition to happiness, we also need meaning in our lives (Smith, 2013; Wong, 2014b). Most of the PP of happiness is based on the assumption that happiness is the final good, and that we can live a happy life by directly pursuing it. In contrast, Frankl (1985) and Wong (2011) propose that if we pursue meaning instead, happiness will become a by-product of meaning, as explained in the last few lessons. We have already shown that Wong’s (1998a) eight sources of meaning are connected with happiness and made the case that the process of pursuing meaning and self-transcendence is sufficient to endow life with meaning and deep satisfaction (Wong, 2014a), even in difficulty times. King, Hicks, Krull, and Del Gaiso (2006) have found that positive affect and meaning in life are related, and that the former may have more effect on the latter. However, we hypothesize that longitudinal research will show that meaning as measured by active engagement with what really matters and relating well to significant people in our lives will predict positive affect more than the reverse. Pattakos and Dundon’s (2015) The OPA Way lends support to this meaning hypothesis.

Five Myths of Happiness

- You can have instant happiness.

- You can have lasting happiness.

- Everyone has a fixed set point for happiness.

- Money can buy happiness.

- The happiness formula is a scientific equation.

Recently, Robert Biswas-Diener (2013) has debunked the above myths: “If you think about it, it is nonsensical to speak about 40% of your happiness being the result of personal choices. Further, within an individual it does not make sense to separate genetics from circumstances and personal choices. All three interact and mutually influence one another. In the end, it is the spirit of the pie chart that people warm to: the notion that you have some control over your own happiness. Rest assured, that sentiment is correct.” According to the meaning hypothesis, you can still have authentic happiness even when you go through trying times, because such happiness is not dependent on external circumstances but on living a meaningful life of self-transcendence. Meaning-based authentic happiness needs to be virtuous and balanced. Here are eight simple rules for happiness based on the meaning perspective.

- Freedom of choice: You have the power to choose happiness and not to let anyone disturb your happiness.

- Faith: Beliefs can open up many unexpected blessings.

- Perspective: The right perspective can make all the difference.

- Acceptance: Enjoy who you are and what life offers.

- Values: Devote time to what really matters (relationships and calling).

- Process: The journey is more enjoyable than the destination.

- Contentment: This is the key to wealth and happiness.

- Gratitude: Thankfulness will bring joy to you and others.

Ryff and Singer (2008) provide a comprehensive picture of happiness that is consistent with Frankl’s (1985) meaning orientation. They recognize that the natural way is the best way to achieve well-being based on taking personal responsibility for meaningful living and positive relationships. These components of well-being fall under a broad umbrella of eudaimonic well-being, described above as a sense of fulfillment or flourishing from the pursuit of meaning and virtue, which comes from a term used by Aristotle to describe the highest of all human good. Thus, authentic happiness is consistent with the noble aspects of human nature. Such happiness is intrinsic and less dependent on external circumstances.

Take-Home Message

Authentic happiness is primarily based on fulfilling the good and noble aspects of human nature (e.g., spiritual yearnings for meaning, connectiveness, and virtue) or humanistic values rather than practicing happiness-enhancing activities.

Discussion Questions

- Is it possible for you to find authentic happiness without being true to yourself?

- Do you think that who you are is more important than what you do? Why?

- How can we find happiness amidst suffering?

Exercises

- Try to help someone who is less fortunate than you. Describe how you feel afterwards.

- If you are bored with pleasurable activities, try something that challenges your intellect, skills, or courage.

- Discover the joy of letting go of something that has been bothering you.

Resources

- Wong’s (2011) “Four Types of Happiness” (wordpress.com/2011/12/12/4-types-of-happiness/)

- Robert Biswas-Diener’s article, “Five Myths of Positive Psychology” (http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/significant-results/201304/5-myths-positive-psychology)

- Emily E. Smith’s article, “There’s More to Life than Being Happy” (theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/01/theres-more-to-life-than-being-happy/266805/)

Lesson 7: How Do I Maintain Hope in Desperate Situations? Tragic Optimism

Chance and fate intervenes. Bad things happen. The best-planned project goes wrong. In this world, nothing is certain and nothing can be guaranteed—macro forces can defeat even our best and most careful efforts. The challenge is this: How can we maintain a sense of hope in a meaningful future in desperate or seemingly hopeless situations? It took the horror of Nazi death camps for Dr. Viktor Frankl (1985) to discover the power of tragic optimism (TO). He defined TO as “an optimism in the face of tragedy” (p. 162). His chapter on the case for TO “addresses present day concerns and how it is possible to ‘say yes to life’ in spite of all the tragic aspects of human existence. … It is hoped that an ‘optimism’ for our future may flow from the lesson learned from our ‘tragic’ past” (Frankl, 1985, p. 17). All the horrors of atrocities, all the dehumanizing deprivation and degradation, and all the pains inflicted on him by his tormentors could not strip him of his human dignity and his abiding hope in the meaning and value of life. His own defiant spirit and courage in the most hopeless, helpless situation bears witness to the power of TO. In addition to the defiant attitudinal value, he also enjoyed the experiential value of watching a beautiful sunset and the creative value of working on his book with scraps of paper. Thus, he demonstrated that by meditating on the meaning triangle, we can experience meaning and optimism. As Frankl (1985) puts it, [People] can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress. We who lived in concentration camps can remember the [people] who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a [person] but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. (p. 86) Unlike other kinds of hopes, TO cannot be crushed by adversities or catastrophes because, like true gold, it is purified in the crucible of suffering and rooted in an abiding inner value. Frankl (1985) aptly states, “The consciousness of one’s inner value is anchored in higher, more spiritual things, and cannot be shaken by camp life” (p. 83).

Wong’s Five Ingredients of Tragic Optimism

Wong (2005) has developed a psychological model of TO and proposed that it comprises the following components:

- Acceptance of what cannot be changed. By definition, TO depends on confronting and accepting the bleak reality as experienced. Unless and until one fully accepts the dark sides of life and a pessimistic assessment of grim reality, without delusional or defensive attributions, one cannot discover TO.

- Affirmation of the inherent meaning and value of life. This is the turning point. The affirmation of life is the cornerstone of TO. Without firmly believing in the possibility of meaning in all aspects of human existence, in the intrinsic value and dignity of human life, it would be difficult to experience optimism in the face of tragedy.

- Self-transcendence. This represents an action dimension of stepping out of oneself and becoming re-oriented towards helping others or serving a greater purpose.

- Faith in a higher being and/or in others. Faith is crucial to tragic optimism. Faith in a higher being and prayer has been a source of strength and optimism to countless individuals in practically hopeless situations. Faith represents a flickering light at the end of the tunnel. Often, it is the only positive expectation in an otherwise dark and hopeless world. For those who do not believe in a higher being, the best thing they can do is to place their faith in others.

- Courage to face and overcome adversity. Courage may be considered the master virtue, because all the other components hinge on courage—the heroic and defiant human spirit. Acceptance requires courage; so does affirmation. Stepping out of our comfort zone to help others or to serve a greater purpose also requires the courage to be vulnerable. One cannot be optimistic without the courage to face an unknown and uncertain future. One cannot be optimistic about one’s own competency without the courage to take on a challenging task and risk failure.

Take-Home Message

Happy people are optimistic; you can maintain hope in desperate situations if you exercise the meaning triangle and practice the five elements of tragic optimism.

Discussion Questions

- Is it possible to maintain hope in desperate situations without faith?

- Why is it that people are more likely willing to help each other in desperate times?

- What makes TO stronger than other types of hope that are simply based on positive thinking and confidence in one’s own competence?

Exercises

- How does meaning make tragic optimism stronger than other types of hope that are simply based on positive thinking and confidence in one’s own competence?

- Think of a task that you have been avoiding because of its difficulty and high risk of failure. How would the concept of tragic optimism empower you to complete this task?

Resources

- Paul T. P. Wong’s article, “Viktor Frankl: Prophet of Hope for the 21st Century” (meaning.ca/archives/archive/art_frankl_prophet_P_Wong.htm)

Lesson 8: What are the Practical Steps to Build Resilience? The ABCDE Model

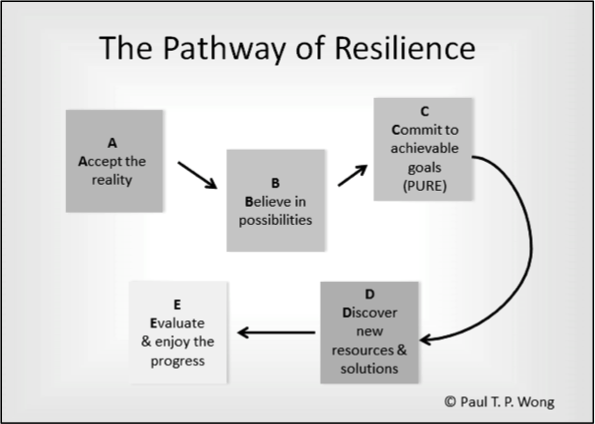

It takes resilience to bounce back after failure and setback. The defiant human spirit and the human capacity for meaning-making are very powerful tools at our disposal. Wong’s ABCDE model (Wong, 2012c) incorporates both the meaning triangle and Wong’s (2005) tragic optimism (TO) as a framework to overcome and transcend all kinds of adversities. There are two possibilities after a tragic or traumatic event. Some become bitter and experience depression or post-traumatic stress disorder, while some become better and experience post-traumatic growth. The vastly different outcomes depend on how one copes with the trauma. The ABCDE strategy, as shown in Figure 4, incorporates Frankl’s teaching on how to cope with suffering (Lukas, 2014) as well as research on stress and coping (Wong, 1993).

Figure 4. The ABCDE model is a meaning-centered pathway of resilience.

The ABCDE Model

The following are the components of the pathway of resilience.

- Acceptance: the reality principle. Acceptance does not mean giving up or resignation; it simply means accepting what cannot be changed—the trauma, the loss, and the dark side of the human condition. It means accepting areas of “fate” which are beyond our control with courage and hope.

- Belief: the faith principle. Belief primarily means affirming the three basic tenets of logotherapy. It means that there is always some area of freedom in which we can act responsibly and courageously. In the worst-case scenario, we still have the freedom of taking a stand, adopting a defiant attitude, or maintaining faith in a higher being or others. Finally, it also involves affirming one’s ideals, core values, worthwhileness, and competence.

- Commitment: the action principle. Commitment simply means moving forward and carrying out one’s responsibility with resolve, regardless of feelings or circumstances. This brings us back to the PURE strategy of striving to fulfill one’s responsibility no matter what, because it is the right thing to do and it is part of one’s life mission. Real change is possible only when one takes the first concrete step in a new direction.

- Discovery: the ‘Aha!’ principle. Discovery involves learning something new about the self and life. It means that as we dig deeper into our resources and explore further, we discover hidden strengths and resources. This is consistent with Wong’s (2012e) deep-and-wide hypothesis of the adaptive benefits of adversity and negative emotions.

- Evaluation: the self-regulation principle. Evaluation means continuing to monitor and make the necessary adjustments to ensure some progress. If nothing seems to work and there is no reduction of symptoms and no improvement in the pursuit of positive life goals, then some adjustments will be necessary. This involves reflecting on one’s life and assessing the opportunities and risks.

Take-Home Message

Resilience depends on your ability to tolerate and transform adversity. No matter how bad things are, you can always turn adversity into achievement if you practice ABCDE.

Discussion Questions

- What are some things about yourself or your life that you find difficult to accept? What are the barriers to acceptance? Discover what happens when you fully accept those aspects of yourself or your life.

- What are some of the beliefs that sustain you and give you hope during difficult times?

- Recall a situation in which your belief or faith was the only thing you could hang onto in order to survive.

Exercises

- Currently, what is the most stressful thing in your life? Apply the ABCDE Strategy and find out whether it works for you.

- Discover an area of freedom in which you can exercise any of the three values of Frankl’s meaning triangle, and discover whether it affects your life in a positive way.

Resources

- Paul T. P. Wong and Lilian C. J. Wong’s (2012) chapter, “A Meaning-Centered Approach to Building Youth Resilience.” (drpaulwong.com/documents/HQM2-chapter27.pdf)

Lesson 9: How Do I Live Life to the Fullest? The Yin-Yang Way.

Take-Home Message

Just remember that what seems like a misfortune may turn out to be a blessing in disguise.

Discussion Questions

- In what ways does the dual-systems model give you a sense of freedom or hope when you feel overwhelmed by your problems?

- Can you name some of the dangers or risks when everything is going your way?

- Try to apply the dual-systems model to solve a current life problem.

Exercises

- Count your blessings in a negative situation you are currently experiencing.

- Consider the hidden dangers of success when all your dreams are realized.

- In everyday situations, how do you balance the positives and the negatives so that you feel good at the end of each day?

Resources

- Jeanne Segal’s Emotional Intelligence Toolkit (helpguide.org/emotional-intelligence-toolkit/index.htm)

- Nany Schlossberg’s article, “Happiness is a Balancing Act” (psychologytoday.com/blog/transitions-through-life/201111/happiness-is-balancing-act)

- Jon Gordon’s article, “Working for a Bigger Purpose” (com/working-for-a-bigger-purpose.html)

- The story of the Taoist Farmer (noogenesis.com/pineapple/Taoist_Farmer.html)

Lesson 10: Why Do Other People Matter? The Practical Spirituality of Self-Transcendence

We are all inter-connected in some way. That is both a blessing as well as a curse. We cannot live without other people. We are hardwired for each other—from babies’ attachment to their parents to adults’ bonding with their lovers, intimate relationships are the main source of our security, happiness, and well-being. In addition, a healthy family, community, and society are all built on good interpersonal relationships. One of the challenges before us, as individuals and as a society, is how to strike a balance between self-interest and the welfare of others. Other people matter (Peterson, 2013), because relationships matter a great deal for the good life. To transform an inhumane society into a kinder and gentler community, we need to value people more than self-gain. We all gain at the end when we place other people’s well-being above self-centered concerns. This brings us back to Frankl’s central theme of will to meaning and self-transcendence—the reason as well as the motivation to treat other people in an ethical way as we want to be treated by others. Every time we are activated spiritually by our conscience and sense of responsibility, every time we treat others with dignity and seek to do something for their well-being, we naturally bring happiness not only others but also to ourselves. The golden rule works in every culture, because it honours our spiritual nature for self-transcendence.

Self-Transcendence

Self-transcendence simply means that only when we redirect our focus from self-interest to something bigger than ourselves can we experience meaning in life. Both Abraham Maslow (1993) and Viktor Frankl (1985) have come to the conclusion that self-transcendence represents the highest level of personal development. Frankl is more explicit in pointing out that self-transcendence represents our spiritual nature as well as our deepest yearning. We can discover lasting happiness and deep satisfaction only when we step out of ourselves and serve a higher purpose or greater good. Our spiritual core consists of our innate quest for meaning and self-transcendence. It is our spiritual dimension that separates us from all other creatures and makes us truly human. Frankl’s three levels of self-transcendence are as follows (Wong, 2015):

- Seeking ultimate meaning. To reach beyond our physical and intellectual limitations and gain a glimpse of the invisible wonders of the transcendental realm.

- Seeking situational meaning. To be mindful of the meaning potential of the present moment with an attitude of openness, curiosity, and compassion.

- Seeking one’s calling. To reach beyond self-actualization and pursue a higher purpose for the greater good. This involves engagement and striving to achieve a concrete meaning in life, that is, a life goal of contributing something of value to others.

At all three levels, we are motivated by the intrinsic need for spiritual meaning. If we can cultivate these three levels of self-transcendence, we will develop a spiritual lifestyle that is good and healthy for individuals as well as society. The more we practice self-transcendence based on the meaning-mindset, the more it will be better for others and ourselves. It is a win-win strategy. Self-transcendence is, by definition, intrinsically relational. Vertically, self-transcendence reaches beyond the limits of time and space, to connect with the transcendental realm or to worship and serve a higher being. Throughout his writing, Frankl has made it very clear that his concept of self-transcendence or the supra-meaning transcends specific religious views and resides in the spiritual nature of being human. Horizontally, self-transcendence transcends ego-concerns and self-interest to serve others. It is intrinsically compassionate and altruistic, given its spiritual nature. In self-transcendence, other people matter in their own right because of their intrinsic value. Loving our neighbours is its own reward. Showing kindness to strangers is its own reward. We engage in deeds of compassion and kindness because we are simply expressing our spiritual nature. This is fundamentally different from using other people as instruments for our own advancement and happiness.

Take-Home Message

If we practice the golden rule, which is based on the principle of self-transcendence, we will enjoy better relationships with others.

Discussion Questions

- What would be the best approach to resolving differences rationally without pushing each other’s emotional buttons?

- What are the main differences between self-centered communication and meaning-centered communication?

Exercises

- Think of a relational conflict in your life. What difference would it make if you thought in terms of “we” instead of “me” in this situation?

- Have you ever made amends in order to repair a broken relationship? If not, what holds you back?

- What is your communication style? Do you think that your communication style might be part of your relational problems? Fill out the Individual Communication Style Profile below (Wong, 2013b).

| Individual Communication Style Profile | ||

| © Paul T. P. Wong, PhD | ||

| Cold | |—–1—–2—–3—–4—–5—–| | Warm |

| Laid-back | |—–1—–2—–3—–4—–5—–| | Intense |

| Indirect | |—–1—–2—–3—–4—–5—–| | Direct |

| Guarded | |—–1—–2—–3—–4—–5—–| | Open |

| Judgmental | |—–1—–2—–3—–4—–5—–| | Appreciative |

Lesson 11: What Should I Do When I Feel Stuck? The Double-Vision Strategy

Do you feel trapped in a bad relationship or stuck in a dead-end job? Do you feel discouraged by setbacks because all your struggles seem to be futile? We all have such moments and do not know how to resolve our personal predicaments. This lesson introduces the double-vision strategy, which can be very helpful in problem solving. The paradox is that sometimes the more we focus on finding a solution to these problems, the more confused and frustrated we become. However, when we step back, expand our vision, and look at the big picture, such as the universal human condition or a higher being, we begin to see our problems in a different light—this shift in perspective enables us to find new solutions.

What is Personal is Often Universal

What seems to be a personal problem may be related to a universal human condition. For example, one’s anxiety about sending off a daughter or son to another city for post-secondary education may reflect one’s existential anxiety about aging and dying. The double-vision strategy is helpful in pursuing one’s life goals if you take a larger view of life. When we keep in mind our higher purpose, we will be less likely defeated by small setbacks along the way. To use a chess game analogy, we don’t mind sacrificing a pawn in order to checkmate our opponent’s king. To use a sport analogy, we need to keep one eye on the ball and the other on the goal. The advantage of the double-vision strategy is that it not only allows sufficient space between us and our problems, but also expands our vision so that we can see things more clearly. In this lesson, we will apply this strategy to various cases and demonstrate how it works. When we strive for an ideal as our life purpose, we are more willing to overcome similarly insurmountable problems and hardships. It is by keeping our eye on the big picture that we can deal with small, everyday problems more effectively. It may take years to discover one’s reason for existence. But the difficult quest for one’s calling is both necessary and beneficial. One has the potential to be a force for good only when one dares to discover and pursue one’s higher purpose. If more people are awakened to their true calling of becoming a force for the greater good, the world will become a more harmonious and humane place.

The Double-Vision Strategy

The double-vision strategy simply means you keep one eye on your situational problem and another on your future meaning to be fulfilled. The bigger your vision of the future, the more effective your double-vision strategy. The biggest vision will involve not only the future generations of humanity, but also involve the transcendental realm or a higher being. If you are convicted that you have received a calling from above and are thus striving for the greater good of future generations, then you will not be defeated by opposition, setbacks, or personal problems. The problem with most people is that they never look beyond their self-imposed prison. They never have the courage to venture out of their cave. Therefore, they will only live in a shadowy land without any idea of what life is like under the sun. A person with a double-vision is no longer preoccupied with everyday busyness and personal problems; such people are able to live on a higher plane and at a deeper level, because they know that their transient earthly life is only an instrument for accomplishing something far greater than they are. As one of the most popular Chinese sayings goes, “If you step back from your immediate problem, the horizon will broaden and the sky will open up.” The double-vision strategy represents a change in perspective as well as a change of value from ego to logos.

Take-Home Message

Don’t just look at the tree and forget the forest. Looking at the big picture can broaden your outlook on life.

Discussion Questions

- Can you see why “stuckness” is an inevitable part of the human condition?

- Why is that without a vision, we don’t go very far?

- What is a current problem in which you feel stuck? How would you see this problem differently if you used the double-vision strategy?

Exercises

- How does the double-vision strategy make your life happier and more productive?

- Learn to pause and reflect. This exercise of self-reflection is an effective way to ponder the big picture. For example, reflect on the questions, “Who am I?” “What is my place in the universe?” “What is my life mission?” or “What is God’s purpose for my life?”

- Is it worthwhile to devote one’s life to pursuing one’s calling, even when it does not yield any monetary reward or recognition?

Resources

- Robert Emmons’ chapter, “Personal Goals, Life Meaning, and Virtue: Wellsprings of a Positive Life (psychology.hku.hk/ftbcstudies/refbase/docs/emmons/2003/53_ Emmons2003.pdf)

- Douglas LaBier’s article, “Why It’s Hard to Find Your ‘Life Purpose’ in Today’s World” (psychologytoday.com/blog/the-new-resilience/201105/why-its-hard-find-your-life-purpose-in-todays-world)

Lesson 12: Learn The Meaning-Centered Pathways to Well-Being

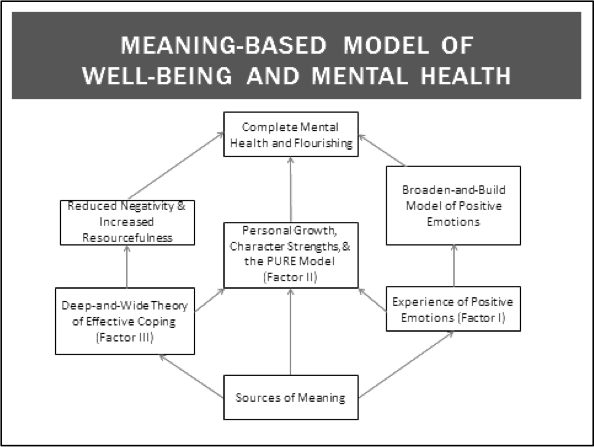

We have now come to the end of our journey of self-discovery. We are now able to pull all the lessons together and have an overview of how meaning plays a central role in living the good life. Meaning not only leads to well-being, but also protects us against distress. Snyder and Lopez (2007) are correct in proposing the formula: Happiness + Meaning = Mental Health. Wong (1998a) has found that the sources of meaning predict both the presence of well-being and absence of mental illness. This has been replicated and extended to prospective studies (Mascaro, 2014; Mascaro & Rosen, 2008). However, when people are going through very difficult times, meaning, rather than positive emotions, becomes more important in maintaining some level of well-being (Frankl, 1985; Wong, 2011). According to the meaning-centered approach to well-being, the ABCDE strategy serves the function of transforming negatives into positives, as well as making suffering more bearable. The ABCDE acronym stands for acceptance, belief, commitment, discovery, and enjoyment/evaluation. A detailed account on how these components contribute to resilience and well-being in adverse situations have been given by the present author (Wong, 2010b; Wong & Wong, 2012). In addition, the important role of hope in maintaining one’s well-being and health has been well documented (Snyder, 2000). Hope provides the motivation to strive and improve one’s life. However, in extreme situations, such as the Holocaust or dying from incurable cancer, one needs a different kind of hope, which is found in Frankl’s (1985) concept of tragic optimism. Therefore, meaning provides at least three pathways towards a healthier and happier life that is both resilient and optimistic. When we cultivate the meaning-mindset and practice self-transcendence, we are on a very promising path towards healing and wholeness. More recently, Wong (2014c) has provided a more detailed integrative model indicating how meaning contributes to our well-being, as seen in Figure 6.

Take-Home Message

The pursuit of meaning offers us the best protection against adversity and the most promising pathway to living a happy and healthy life.

Discussion Questions

- What are the advantages of the meaning approach to positive mental health as compared to the traditional emphasis on happiness and positive emotions?

- Which is more important in mental health: Is it the cultivation of positive meaning and happiness or the transformation of negative emotions and adversity? Why is it that the ideal way is to embrace both the approach and avoidance tendencies?

Exercises

- Identify an unhappy situation in your life. Try to use meaning-seeking or meaning-making as a way to help you feel better.

- Describe an experience in which you felt good about yourself in going through a very difficult situation because of your decision to practice self-transcendence.

- How will you use the meaning approach to help a friend who is struggling with depression, anxiety, or despair?

Meaning Manifesto

Life is much more than the everyday busyness of making a living or striving for personal success. Life is much more than a constant struggle of coping with harsh realities by fighting or escaping. Life can be lived at a deeper level and on a higher plane by adopting a meaning-mindset as your basic life orientation. Your life has intrinsic meaning and value because you have a unique purpose to fulfill. You are endowed with the capacity for freedom and responsibility to choose a life of meaning and significance. Don’t settle for anything less. No matter how confusing and bleak your situation, there is always beauty, truth, and meaning to be discovered, but you need to cultivate a mindful attitude and learn to transcend self-centredness. Don’t always ask what you can get from life, but ask what life demands of you. May you be awakened to your sense of responsibility and the call to self-transcendence. You become fully human only when you devote your life to serving a higher purpose and the common good. Let your inner goodness and conscience be your guide. Let compassion be your motive and may you see the world and yourself through the lens of meaning and virtue. You will experience transformation and authentic happiness when you practice meaningful living. Now, go forward with courage and integrity and pursue your ideals against all odds with the defiant human spirit.

Conclusion

The Meaningful Living Group concludes with the above meaning manifesto, which summarizes the main points of the 12 lessons. We celebrate the conclusion of the MeetUp with a communal meal and the awarding of certificates of completion. As a result of participating in the group, several members realized that they needed professional help for their unresolved issues, but most participants were able to make use of some of the existential positive interventions to make their lives happier and more meaningful. The materials for meaningful living group have been adopted by correctional services, addiction recovery, and other meetup groups. This chapter has provided a framework to teach people the art and science of meaningful living, but it is still too early to document empirically the benefits of this meaning-centered positive group work.

Key Takeaways

- There is mounting evidence in the research literature concerning the vital role played by meaning in life in enhancing well-being and buffering against stress. Meaning-centered positive group work has much to contribute to the mental health movement because it educates participants regarding their essential need for meaning and the basic principles and skills of meaningful living.

- This group intervention is based on both the positive psychology research of meaning and the existential insights and principles of Frankl’s logotherapy and Wong’s integrative meaning-centered therapy. Therefore, it can be used for both community-based groups interested in personal development and various clinical groups that address meaning in life issues.

- For each session, the group activity consists of a mini lecture by a psychologist, followed by group discussions and take-home exercises. All activities are designed to focus on the optimistic outlook of positive changes regardless of circumstances.

- The twelve lessons cover important questions such as “Who am I?” “What really matters in life?” and “How can I find happiness in difficult situations?” These lessons draw upon scientific findings and clinical insights. The applications of the principles of meaningful living answer these universal concerns while taking into account each participant’s personal context.

- Participants learn Frankl’s concept of the meaning-mindset. When life is viewed from this perspective, life takes on more meaning; even adversities are transformed into challenges and opportunities. Participants also learn the Yin-Yang principle of existential positive psychology, which is capable of transforming all negative life experiences into ones that are positive.

References

- Anders, M. (2012). What you need to know about spiritual growth: 12 lessons that can change your life. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. Anderson, K. (2013, Mar/Apr). Suffering and the quest for wisdom.

- Anderson, K. (2013, Mar/Apr). Suffering and the quest for wisdom. Psychotherapy Networker. Retrieved from http://www.psychotherapynetworker.org/magazine/currentissue/item/ 2094-dark-passage

- Batthyany, A., & Russo-Netzer, P. (Eds.). (2014). Meaning in positive and existential psychology. New York, NY: Springer.

- Biswas-Diener, R. (2013, Apr. 1). 5 myths of positive psychology. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/significant-results/201304/5-myths-positive-psychology

- Breitbart, W., Rosenfeld, B., Pessin, H., Applebaum, A., Kulikowski, J., & Lichtenthal, W. G. (2015). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy: An effective intervention for improving psychological well-being in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(7), 749-754. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2198

- Christensen, C. M. (2012). How will you measure your life? New York, NY: Harper Business.

- Conley, C. (2010). Chip Conley: Measuring what makes life worthwhile [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UROCz70tlMY

- Corey, G. (2009). Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Dezelic, M. S., & Ghanoum, G. (2015). Meaning-centered therapy manual: Logotherapy and existential analysis brief therapy protocol for group and individual sessions. Coral Gables, FL: Dezelic & Associates.

- Ebrahimi, N., Bahari, F., & Zare-Bahramabadi, M. (2014). The effectiveness of group logotherapy on the hope among the leukemic patients. Iranian Journal of Cancer Prevention, 7(1), 9-16. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4142957/

- Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. In C. L. M. Keyes (Ed.), Flourishing: The positive person and the good life (pp. 105-128). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Frankl, V. E. (1988). The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of logotherapy (Expanded ed.). New York, NY: Meridian.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Ghamari, M. (2013). Effectiveness of group counseling with logotherapy approach on college students quality of life. Contemporary Educational Researches Journal, 3(1), 6-11. Retrieved from http://www.world-education-center.org/index.php/cerj/article/view Article/3355

- Gordon, J. (n.d.). Working for a bigger purpose. Retrieved from http://michaelhyatt.com/working-for-a-bigger-purpose.html

- Hicks, J. A., & Routledge, C. (Eds.). (2013). The experience of meaning in life: Classical perspectives, emerging themes, and controversies. Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jung, C. G. (1962). Memories, dreams, reflections. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychologist, 90(1), 179-196. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179

- LaBier, D. (2011, May 24). Why it’s hard to find your “life purpose” in today’s world. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-new-resilience/201105/why-its-hard-find-your-life-purpose-in-todays-world

- Lantz, J. (1998). Viktor Frankl and interactional group therapy. Journal of Religion and Health, 37(2), 93-104. doi:10.1023/A:1022922713843

- Leontiev, D. A. (2015). Experience processing as an aspect of existential psychotherapy: Life enhancement methodology. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 45(1), 49-58. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10879-014-9284-x#page-1

- Lukas, E. (1986/2014). Meaning in suffering: Comfort in crisis through logotherapy. Birmingham, AL: Purpose Research.

- Lukas, E. (1991/2015). The therapist and the soul: From fate to freedom. Charlottesville, VA: Purpose Research.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). The how of happiness: The scientific approach to getting the life you want. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Mascaro, N. (2014). Meaning sensitive psychotherapy: Binding clinical, existential, and positive psychological perspectives. In A. Batthyany and P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in positive and existential psychology (pp. 269-289). New York, NY: Springer.

- Mascaro, N., & Rosen, D. H. (2008). Assessment of existential meaning and its longitudinal relations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(6), 576-599. doi:10.1521/jscp.2008.27.6.576

- Maslow, A. H. (1993). The farther reaches of human nature. City of Westminster, UK: Penguin

- May, R. (2009). Man’s search for himself. New York, NY: WW Norton.

- McDonald, M. J., Wong, P. T. P., & Gingras, D. T. (2012). Meaning-in-life measures and development of a brief version of the Personal Meaning Profile. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 357-382). New York, NY: Routledge.