Abstract

This chapter first argues the need for second wave positive psychology (PP2.0), which is informed by Frankl’s logotherapy as well as existential psychology. The main thesis of PP2.0 is that in order to attain healing and authentic happiness, one needs to confront the dark side of human existence and pursue self-transcendence—going beyond oneself to serve something greater. The chapter then introduces integrative meaning therapy and its existential positive interventions, representing the applications of PP2.0. The main contributions of this chapter are that it brings out the positive aspects of existential therapy and adds a new dimension of existential concerns to positive psychology as usual.

Keywords: Viktor E. Frankl, logotherapy, self-transcendence, existential psychology, positive interventions, meaning therapy

Introduction

This chapter focuses on meaning-enhancing positive interventions from both positive psychology (PP) and existential psychology perspectives. It is a continuation of the same endeavour found in the current author’s previous chapter on Frankl’s meaning-seeking model (Wong, 2014). This earlier chapter focused on the intersection and integration of Frankl’s concepts and PP research on meaning. The present chapter goes one step further by focusing on the underlying paradigm that facilitates such integration for both research and interventions.

More specifically, the current chapter makes the case that integration between PP and existential psychology results in existential positive psychology (EPP) (Wong, 2010), which is largely inspired by Frankl’s theme of positive meaning potentials in sufferings. This logical progression can be referred to as Second Wave Positive Psychology (PP2.0) because it represents a synthesis of thesis (negative existential focus) and antithesis (PP1.0). Thus, the emerging PP2.0 is an inevitable scientific progression and provides the proper paradigm for meaning-oriented research and interventions.

Given the mounting evidence regarding the vital role of meaning in well-being and healing (Batthyány & Russo-Netzer, 2014; Steger, Sheline, Merriman, & Kashdan, 2013; Wong, 2012a), it is expected that meaning-enhancing interventions are important in applied PP. Unfortunately, meaning-oriented interventions remain underdeveloped, as compared to happiness-inducing interventions and strengths-enhancing interventions. In contrast, both logotherapy (Frankl) and meaning therapy (Wong) focus almost exclusively on meaning-enhancing interventions.

Part of the reason for the lack of development in meaning-enhancing interventions in PP may be due to the assumption that when people are happy and successful, meaning is superfluous—there seems to be no need for meaning. Therefore, PP has devoted most of its energy to happiness research and happiness-inducing interventions.

From both personal experiences and research, it is known that people are more likely to engage in a quest for meaning when things go wrong (Wong & Weiner, 1981). Furthermore, meaning makes suffering more bearable and enables people to be more resilient (Frankl, 1985; Wong & Wong, 2012). In fact, most of the profound insights into meaning in life have been discovered by those who have gone through extreme suffering (Frankl, 1985; Guttman, 2008).

This chapter proposes PP2.0 (Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2015; Wong, 2011) as the necessary paradigm for meaning-oriented interventions. The main differences between the beginning stage of PP and PP2.0 will be discussed in detail later in this paper. Suffice to say that PP2.0 has become necessary for two main reasons:

- The simple-minded focus on only the positive is no longer defensible because positives and negatives are often connected—there is a bright side to the negatives and dark side to the positives. Therefore, the dialectic rather than binary principle is more applicable to the reality of human experiences.

- Life is hard and full of suffering for most people. One cannot focus on the pursuit of happiness and assume that the problem of suffering will simply go away. PP2.0 emphasizes that one needs to confront and embrace the dark side of human existence in order to achieve authentic happiness and resilience.

Since PP2.0 is informed by existential psychology and based on the insights of Frankl, it is also known as existential positive psychology (EPP) (Wong, 2009, 2010). Thus, the unique contribution of PP2.0 or EPP is that it maintains the importance of confronting the dark side of human existence in order to achieve meaning, authentic happiness, and resilience.

From the perspective of PP2.0, this chapter will first introduce logotherapy and classical logotherapy interventions. Then, it will introduce integrative meaning therapy, which extends logotherapy by incorporating existential positive interventions. In other words, integrative meaning therapy is broader than logotherapy and includes other positive interventions (e.g., the gratitude exercise) that are informed by PP2.0 and have meaning as their underlying integral construct.

Research has consistently demonstrated that our behaviour is a function of person-situation interactions (Mischel, 1996). However, PP2.0 or EPP proposes that, at a deeper level, our behaviour is also a function of the interaction between personal beliefs and the universal condition of human existence. For example, according to a well-known saying from William James, “Believe that life is worth living, and your very belief will help create the fact” (James, 2000, p. 240). Thus, if we believe that there is inherent meaning in the human condition regardless of circumstances, such affirmation will have an overall adaptive influence on a person’s behaviour in various situations. The adaptive benefits of functioning beliefs are a fruitful area of PP research.

Meaning Enhancing Positive Interventions from PP1.0

The most commonly recommended positive interventions include enhancing positive emotions, expressing gratitude, and identifying character strengths followed by finding new opportunities to use them (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). There are actually very few meaning-enhancing interventions in the PP literature. Most of the publications in this area are written by Parks and Rashid, the two co-authors of Seligman’s initial article on positive psychotherapy (Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006).

In a recent review article, Parks and Biswas-Diener (2013) ask the rhetorical question whether positive interventions are just “selling old wine in a new bottle” (p. 140). In fact, most of the positive interventions reported predate Seligman’s launching of the PP movement in 1998. What makes the current research on positive interventions unique is its experimental rigor.

Sin and Lyubomirsky (2009) define positive interventions as those aimed at cultivating positive feelings, positive behaviours, or positive cognitions. Parks and Biswas-Diener (2013) define positive interventions in terms of their focus on positive topics; positive mechanisms or positive outcome variables; and promoting wellness rather than fixing weaknesses. Most PP interventions are designed to help the non-distressed improve themselves rather than to provide therapy for the clinical population (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013).

More recently, Foody, Barnes-Holmes, and Barnes-Holmes (2013) provide a more complete statement regarding positive psychology interventions:

The primary goal of positive psychology is to identify the positive aspects of an individual’s personality and to harness these in the service of achieving optimum human functioning. In other words, strategies for promoting well-being lie at the heart of this psychological movement. (p. 178-179)

Thus, the domain of positive psychology and positive interventions is clearly oriented towards happiness. In recent years, meaning has emerged as a hot research area for positive psychology (Batthyány & Russo-Netzer, 2014; Hicks & Routledge, 2013; Wong, 2012b). However, both the PP literature and the current author’s personal conversations with leading positive psychologists indicate that there has been less research on meaning-enhancing interventions as compared to happiness-inducing or strengths-based interventions.

Empirical Support for Positive Meaning Interventions

Parks and Biswas-Diener (2013) provide a balanced review of positive interventions, pointing out both their successes and limitations. Surprisingly, the only meaning intervention they covered was expressive writing. They are correct in pointing out that most meaning interventions involve personal narratives to make sense of traumatic or stressful events (e.g., Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999). In contrast, the benefits of expressive writing on positive experiences are less clear-cut. Lyubomirsky, Sousa, and Dickerhoof (2006) found that participants who wrote about a past positive event reported lower life satisfaction as compared to a control group. Writing about one’s positive future was beneficial (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006), but Parks and Biswas-Diener point out that even this approach did not work with some individuals.

Parks and Biswas-Diener’s (2013) coverage of interventions related to social connections is relevant to meaning intervention, since meaning is generally defined as service to others (Frankl, 1985; Seligman, 2004). This area of research is primarily related to altruistic behaviours towards others. Dunn, Aknin, and Norton (2008) report that spending money on others results in enhanced happiness, and this finding has been replicated in many other countries (Aknin et al., 2013).

Parks and Biswas-Diener (2013) conclude that manipulations that increase social connections can enhance personal happiness. From a meaning perspective, such manipulations result in happiness precisely because it is a natural by-product of serving others or self-transcendence, as Frankl (1985) has maintained. Consistent with the enduring spiritual teaching that it is more blessed to give than to receive, Frankl nails down the biggest spiritual secret of living a meaningful and fulfilling life—we do not ask what we can get from life, but ask what life demands of us. Such self-transcendence is the key to meaning and happiness, because it is at the heart of our spiritual nature. Unfortunately, obsessed with personal happiness, most first wave positive mental health professionals do not understand the meaning and significance of Dunn et al.’s (2008) finding.

The simple-minded focus on happiness leads to some experiments that are of questionable value from a meaning perspective. For example, Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, and Schkade (2005) investigated whether engaging in an act of kindness per day for a week or five acts of kindness in a single day leads to increases in well-being. This is an interesting study with respect to personal happiness, but from the standpoint of meaning, it has dubious value. To translate this finding to practice, does it mean that one should refrain from doing a kind deed, even when the situation demands it, so that one can “cash in” more happiness by doing all kind deeds in one day? In other words, does this study encourage callous calculation devoid of compassion? Wouldn’t we rather encourage people to perform random acts of kindness everyday, because this is good for both those who practice it and their society?

The same can be said about gratitude exercises. Parks and Biswas-Diener (2013) point out that sometimes such exercises may actually result in negative feelings rather than increased happiness. For example, Parks recognizes that the Gratitude Visit exercise does not work or even backfires for some individuals from Asian-American backgrounds (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013). Does this mean that gratitude is desirable only in certain situations, simply because it does not increase one’s happiness? Shouldn’t one rather maintain an attitude of gratitude for the overall benefit of improving one’s relationships and spiritual maturity at a deeper level?

In Buddhist psychology, as well as in traditional cultures, there is a consistent teaching that people should be grateful. Take, for instance, the popular Chinese saying, “Whenever you drink, remember its source.” This means that when you eat, be grateful to the farmers who grew the crops and the cook who prepared the dish for you. When you are aware of your existence, be grateful to your parents who gave birth to you and raised you. Such teachings on attitude change can avoid the problem of doing contrived gratitude exercises inappropriately, whether it is sending a gratitude letter or paying a gratitude visit.

A positive attitude of gratitude has more to do with virtue rather than personal feelings of happiness. One may express such gratitude in the appropriate manner that is called for by each situation. Frankl (1985) consistently emphasizes the importance of situational demands and the need to be sensitive to their meaning potential. This contextual approach is clearly more realistic and flexible than the prescription of any specific gratitude exercise.

Recently, Foody, Barnes-Holmes, and Barnes-Holmes (2013) emphasized that “gratitude exercises should avoid a focus on what is felt over what is valued in order to encourage self as process” (p. 188). Similar, in meaning therapy, gratitude interventions focus on the virtue and process of becoming a better and more grateful person, because such an appreciative and grateful attitude may have more pervasive benefits on well-being and meaning.

Positive Psychotherapy

Another area of applied PP is positive psychotherapy (PPT) (Seligman, Rashid & Parks, 2006). Recently, Rashid et al. (2014) have provided a detailed description of PPT:

PPT, unlike traditional therapeutic paradigms, purports that problems do not necessarily reside entirely inside participants. Hence, it is not in favor of the New Age mantra: To Change Life, Change Your Attitude. Instead, PPT acknowledges that well-being and depression are engendered and maintained by complex interactions between individuals and their environments. PPT doesn’t purport to oversimplify this complexity. It weighs symptoms and strengths, vulnerabilities and opportunities, skills and deficits realistically—without minimizing or ignoring either. In this regard, Positive Psychotherapy is a misnomer; we would prefer to call it a balanced therapy—but it is far less appetizing than PPT. In striking the balance, PPT equally considers positive emotions and strengths and negative symptoms and disorders. (p. 162)

Clearly, the description emphasizes the need to strike a balance between “symptoms and strengths, vulnerabilities and opportunities, skills and deficits realistically” (Rashid et al., 2014, p. 162). However, in a careful examination of the actual session-by-session description, the present author has found little evidence of a balanced approach that pays equal attention to symptoms, weaknesses, and negative emotions. Most of the sessions cover the typical PP variables, such as positive emotions, character strengths, and gratitude.

Their only reference to the dark side is about “bad memories.” Consistent with their positive bias, bad memories are interpreted as being bad for you: “the role of bad memories is discussed in terms of how they undermine one’s resilience” (Rashid et al., 2014, p. 164). In contrast, from a meaning perspective, bad memories can be good if one learns to confront, transcend, and make a coherent narrative out of them.

Moreover, there is no evidence that meaning is included in the program, even though they claim that PPT is designed to build “positive emotions, strengths, and meaning, in addition to undoing symptoms” (Rashid et al., 2014, p. 161; emphasis mine).

Another limitation of PPT is that it attempts to dismiss the importance of attitude change in transforming one’s life. Attitude change is not simply a “New Age mantra.” There is substantial literature on the psychology of attitude change. An attitude is “a relatively enduring organization of beliefs, feelings, and behavioural tendencies towards socially significant objects, groups, events or symbols” (Hogg & Vaughan, 2005, p. 150). As such, interventions designed to change one’s attitude may have more pervasive and enduring effects than interventions focused on behavioural or cognitive change. Attitude modification is an essential part of logotherapy and meaning therapy. Future research is needed to determine the relative efficacy of meaning-oriented attitude modification as compare to happiness-oriented positive interventions.

Mainstream mental health professionals have also recognized the importance of meaning in life in psychotherapy (Hill, Kline, et al., 2015; Ryff et al., 2014).

The cure is thus not defined by the alleviation of emotional discomfort, or the attainment of some ideal feeling state, but by being able to take constructive action in one’s life—i.e., being able to live a full and meaningful existence, rather than be ruled by passing emotions. (Ryff et al., 2014, p. 12)

Recent attempts to integrate PP and action and commitment therapy (ACT) (Kashdan & Ciarrochi, 2013) have significantly expanded meaning-oriented interventions and moved closer to logotherapy and meaning therapy in terms of placing more emphasis on values and actions rather than the feeling good and hedonic outcome measures. In doing so, they provide a “framework for sustaining fulfillment even in the face of pain and setbacks” (Steger et al., 2013, p. 243).

Steger et al.’s (2013) chapter is exceptionally helpful in introducing meaning-oriented interventions from this new framework. This approach offers “‘larger and larger patterns.’ Meaning in life research directly addresses how behaviours and values, as a holistic unit, bring one’s life into harmony by serving a greater purpose” (Steger et al., 2013, p. 262). They recognize the following main themes that are closely related to logotherapy and meaning therapy.

- Mobilizing values. The aim of this intervention is to identify and explore the values that clients can act on. For example, one can ask clients to talk about “what they stand for, what they believe in, what makes them proud about their own conduct, and so on” (Steger et al., 2013, p. 255). This line of questioning serves to push clients to discuss their values that benefit both them and the world.

- What the World Needs Now. This intervention strategy approaches the value issue from what the world demands of the client. “Continued dialogue can help clients find the most magnetic need in the world. When paired with the ‘mobilizing values’ intervention, people can be helped to find a purpose they care about and articulate some rough ideas about how they would like to pursue it” (Steger et al., 2013, p. 256).

Importantly, Steger et al. (2013) recognize that meaning is inherently related to self-transcendental value:

Although most meaning in life theorists are agnostic about what kinds of meaning are ‘best,’ several have argued that as people mature, their meaning in life becomes increasingly directed at a greater good that transcends their momentary, individualistic desires. This notion of self-transcendence is often a descriptor used of people experiencing a mindful mindset (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). (p. 261)

However, while they acknowledge the importance of values and self-transcendence, their epistemological assumptions are still similar to those of the earlier stages of PP.

It should also be noted that in the larger literature on trauma and its treatment (Janoff-Bulman, 2006, 2010) as well as post-traumatic growth (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2012), the concept of meaning indeed plays an important role, but such interventions are not generally considered as PP interventions, as PP interventions are generally considered as those based on variables and mechanisms in PP research (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013).

The Need for PP2.0

As stated in the introduction, PP2.0 takes a larger view of recognizing both the infinite human potentials for good and for evil. In other words, it adds an additional existential dimension to provide greater depth for the human phenomena of meaning, happiness, and virtue (Wong, 2015).

Focusing on a person’s strengths does not mean ignoring the dark side of human existence, which includes personal problems and illnesses (Saleebey, 2011). Similarly, Simmons and Lehmann (2013) believe that the most promising positive approach is to simultaneously increase one’s strengths and remediate one’s deficiency. They strongly argue for a balanced approach:

The argument for balance in addressing the human experience in assessment and evaluation is quite the opposite of what has been referred to as the “happiology” construct in which all that matters is a focus on human happiness and well-being (Peterson, 2006, p. 7). As Snyder, Lopez, and Pedrotti (2011) note, “it is very tempting to focus on just the good (or the bad) in the world, but it is not good science and we must not make this mistake in advancing positive psychology” (p. 8). (Simmons & Lehmann, 2013, p. 21)

They also recognize the importance of contributions prior to Seligman’s PP movement. These include transcendent experiences (James, 1902/1958), Frankl’s (1985) concept of self-transcendence, Maslow’s (1943, 1968) self-actualization, Rogers’ (1961) ideas about the fully functioning person, and Antonovsky’s (1979) concept of salutogenesis.

Consistent with logotherapy and meaning therapy, Simmons and Lehmann (2013) emphasize that effective intervention depends on the following foundational assumptions regarding humanistic and existential values:

- Individual value and dignity.

- Optimism in recovery and growth.

- Dialectic perspective of positive and negative.

- Intrinsic meaning in life.

- Personal responsibility and collaborate effects.

With respect to the promotion of meaningful instrumental activities, Proctor and Linley (2014) also advocate a balanced approach to developing both character strengths and relative character weaknesses. As well, they favour a more holistic approach:

Finally, spirituality, positive religious coping, and daily spiritual experiences have also been [shown] to be positively related to positive affect and life satisfaction among young people (Van Dyke et al., 2009). These results suggest that holistic approaches to increasing well-being should consider the use of positive religious coping strategies among youths who are religious and the role of spirituality in early adolescents’ psychological well-being. (Proctor & Linley, 2014, p. 209)

In earlier publications, such as Batthyány and Russo-Netzer (2014) and Wong (2011, 2012b), the differences and similarities between PP and existential-humanistic psychology have been discussed. Table 1 represents a summary of the differences between PP1.0 and PP2.0, which incorporates much of the prior discussions.

| PP1.0 | PP2.0 |

| Dichotomous and binary. | Dialectical and interactive. |

| Focuses on the positive only. | Focuses on both the positive and the negative. |

| Emphasizes positive emotions. | Emphasizes responsible action. |

| Avoids the topics of suffering and death. | Embraces of the topics of suffering and death as pre-condition for authentic happiness. |

| Flourishing achieved through focusing on the positive and avoiding the negative. | Flourishing achieved only through confronting the dark side of human existence. |

| Happiness oriented, self-fulfillment focused. | Meaning oriented, self-transcendence focused. |

| Direct pursuit of happiness may backfire. | Direct pursuit of meaning leads to authentic happiness. |

| Truncated understanding of well-being. | Complete understanding of well-being in the midst of suffering. |

| Focuses on elements of well-being, such as behaviour, cognition, affect, and so on. | Focuses on the whole person, taking a holistic and person-centered approach. |

| Distinct from humanistic-existential psychology. | Informed by humanistic-existential psychology. |

| Based on the positivist paradigm. | Based on the humble science perspective. |

| Based on empirical findings from psychological laboratories. | Based on empirical findings from both psychological and real-life “laboratories.” |

| Based on individualist culture. | Based on both individualist and collectivist cultures. |

Table 1. Contrast between PP1.0 and PP2.0.

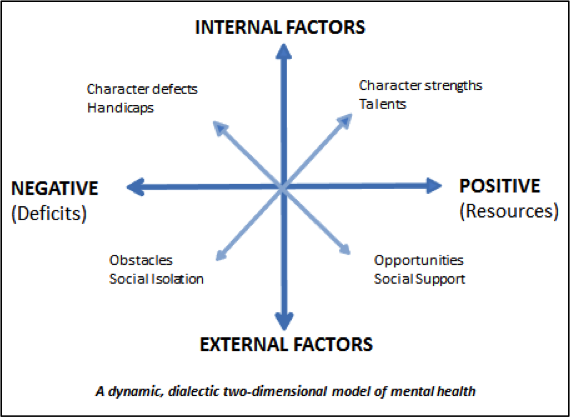

Perhaps the most significant difference is PP2.0’s conceptualization of a dialectic and interactive approach as shown in Figure 1.

According to this model, there are constant interactions between positive and negative sides and internal and external factors. Positive mental health does not only depend on positive internal and external factors; it can also benefit from overcoming character defects and external obstacles. For example, overcoming external obstacles can increase the character strength of persistence, and social support can help a person overcome their handicaps. This interactive model increases both the scope and flexibility of positive interventions.

It is encouraging that leaders in ACT have explicitly recognized the need to move towards PP2.0. Hayes (2013) provides abundant evidence to demonstrate the contextual limits of positive traits as well as the binary dichotomous approach towards human experiences and traits.

Figure 1. A dialectic and interactive model of mental health.

In this area, the acceptance and mindfulness traditions can add something useful to positive psychology as it transitions into ‘Positive Psychology 2.0’ (Wong, 2011). Contextual behavioral scientists and practitioners are well suited to this task because their focus on context affords a more dynamic and less judgmental approach to human experience. (Hayes, 2013, p. 307)

Meaning-Enhancing Interventions in Logotherapy

Lukas (2015) points out logotherapy’s unique contribution of providing positive meaning and healing in times of suffering:

No science can explain the meaning of illness, guilt, and pain in this world. Neither can psychology. But the assertion of the logotherapist is that human beings are fundamentally equipped to find meaning even in illness, guilt, and pain by lifting themselves spiritually beyond them and perhaps even finding their own destiny in the process. (p. 58)

The Objective Criteria of Meanings and Values

The key concept of logotherapy is the will to meaning (Frankl, 1988). Frankl has a unique view of equating the will to meaning with the spiritual nature of self-transcendence. Frankl (1985) recognizes that the perception of meaning is subjective, as it varies from person to person and situation to situation. However, he also points out the main objective criteria of self-transcendence—the touchstone of meaning—getting beyond oneself in the service of God, other people, or a greater cause. Furthermore, bigger is not necessarily better, because a greater purpose needs to be ethically responsible to self, others, and a Higher Authority. Such objective requirements are needed to prevent another Hitler or holocaust. This emphasis on ethical responsibility is missing in positive interventions.

In addition, Frankl (1985) has also identified the following three objectives or enduring values as the pathways of meaning:

- Creative value. Devote your life to do something creative and unique for the well-being of others. Everybody can make a unique contribution; everyone is at least good for something. Remember that it is not the nature of the work or career but the attitude you bring that matters the most.

- Experiential value. Be mindful of what is happening around you rather than always thinking about yourself. Paying attention to what is around you will leave you less time to feel miserable. If you have an appreciative attitude, you will find beauty and meaning even in the most mundane experiences. The idea is getting the focus away from yourself towards what is happening around you here and now.

- Attitudinal value. You can always take the stand of maintaining a defiant attitude. This is the last freedom that no one can take it away from you. This type of spirit says, “You can destroy me, but you cannot defeat me.” It helps maintain human dignity. Being able to exaggerate and laugh at your problems (as in the case of paradoxical intention) reflects this value.

In contrast to the behavioural focus in positive intervention, logotherapy emphasizes the following five attitudes as essential for living a meaningful life (Frankl, 1985):

- An affirmative attitude towards life and human potentials (believing in the intrinsic meaning in life and the human capacity for freedom and self-transcendence).

- A responsible attitude towards life as a whole and the demands of concrete situations.

- A creative attitude towards any kind of work we do (the creative value).

- An appreciative attitude towards life as a whole and daily experiences (the experiential value).

- A defiant attitude towards sufferings that are beyond our control (the attitudinal value).

Furthermore, there are at least five ways to modify one’s attitude according to logotherapy:

- Identify one’s spiritual need for meaning and self-transcendence through Socratic dialogue.

- Distance oneself from the situation and habitual ways of responding.

- Decide to take a positive and defiant stance towards fate and adversity.

- Consult one’s innate conscience and core values.

- Implement an attitude that is consistent with one’s most cherished meaning and beliefs.

The Value of Self-Transcendence

With respect to cultivating an attitude of self-transcendence, Lukas (2015) proposes the following elements in logotherapy:

- Switching from blaming others for problems to assuming responsibility to find solutions.

- Switching from selfish pursuits (ego) to serving others or a worthy cause (logos) as in the case of dereflection.

- Becoming motivated by the fulfillment of spiritual longings rather than immediate need gratification.

- Being willing to suffer and sacrifice for the greater good or a higher purpose.

- Being willing to let go of what cannot be changed and transcend unavoidable suffering and losses.

- Being open to the meaning potentials of every situation and life as a whole.

- Activating one’s spiritual dimension to discover what really matters.

It is particularly worth noting that logotherapy emphasizes the spirit of self-sacrifice, which is missing in other meaning-enhancing interventions. This is the spirit of willingly and intentionally enduring suffering in order to achieve a meaningful goal. Consistent with the thinking of PP2.0, suffering is not only a reality to be accepted, but also a necessity to be embraced in order to survive and thrive. The present author hypothesizes that those who are willing to accept a small self-sacrifice for a worthy cause are more likely to live a meaningful life and achieve some measure of greatness in public or humanitarian services.

According to Lukas (2015),

Frankl wrote about “giving meaning” (Sinn geben) as a form of “sacrificing something” (preisgeben), which must be done for the sake of the meaning to be actualized. Nevertheless, it is extremely difficult for a person spoiled by the affluence of the present Western culture to make a sacrifice, even when it would be meaningful and the value gained would be great. (p. 210)

One of the many profound insights from Frankl is this: sacrifice is a beneficial spiritual exercise in pursuing self-transcendence and meaning.

The present author has recently developed a Self-Transcendence Measure as part of his research related to the Templeton Grant on Virtue, Meaning and Happiness (Wong, 2015). This scale was designed to provide a reliable and valid measure of Frankl’s conceptualization of self-transcendence (Wong, in press).

- I assume full responsibility for my life and my behaviour.

- I consider it a privilege and joy to suffer for my family and friends.

- I take good care of myself so that I can take good care for those who depend on me.

- I contribute money and effort to uplift society and humanity.

- I care about other people’s well-being, even when they are unrelated to me.

- My purpose in life is to serve others, even when it entails personal sacrifice.

- I practice civic responsibility in order to create a better society.

- I experience deep satisfaction from serving God or a great worthy cause.

- I feel spiritually connected with God or the cosmos.

- My faith or hope extends beyond my external situations and physical existence.

- I am responsible to develop my full potential in order to give my best to society.

- I am willing to take risks and accept challenging responsibilities.

Individuals are asked to rate how each statement is characteristic of them on a five-point rating scale, ranging from “Not At All” to “A Great Extent.” This scale can be used for meaning therapy to monitor people’s progress in the pursuit of self-transcendence.

The unique key to healing in logotherapy and meaning therapy is to activate clients’ spiritual will to meaning in a creative way that suits clients’ unique predicaments, personal history, and personality. Such spiritual activation may be summed up as three meaning-enhancing interventions:

- This first step usually involves exploration in past instances or current situations in which clients show some inkling or trace of self-transcendence. That is, times in which they express selfless interest in another person or a worthy cause and some urge or personal responsibility to do what is right or what really matters.

- The second step involves helping clients gain some insight of the noble, spiritual side of themselves that is so different from their culturally-conditioned egotistic, materialistic thinking. It is like a ray of light breaking through the darkness and ignorance of their mind regarding the spiritual virtue of self-transcendence.

- The third step involves awakening the clients’ willingness to implement their insights, knowing that people are not only good and life is not like living in Disneyland. Only through a bold and realistic view that people are capable of both good and evil and the world is full of potential for meaning and goodness in the midst of suffering, violence, and death can we develop a positive psychology robust enough to be relevant to the suffering masses.

Wong’s Existential Positive Interventions

The present author’s integrative meaning therapy (MT) is an intervention that evolves from Frankl’s logotherapy (Wong, 2012a). Different from Frankl’s classic logotherapy, MT is pluralistic and emphasizes the application of contemporary meaning research findings, such as in the sources of meaning (Wong, 1998), the meaning-mindset (Wong, 2012c), and components of meaning (Wong, 2011). A good example of such integration can be found in the current author’s chapter on Frankl’s meaning-seeking model (Wong, 2014).

The Practice of Integrative Meaning Therapy

MT is actually a pluralistic approach (Cooper & McLeod, 2010), open to incorporating cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), narrative therapy, and so on. For example, there are at least five ways to overcome irrational anxiety according to MT. The following shows a combination of CBT, MT, and logotherapy:

- Recognize that the anxiety is irrational (Rational thinking).

- Exaggerate it to the point of laughing at it (Paradoxical intention).

- Stop rumination and switch attention to a worthy task (Dereflection).

- Recognize it is of no consequence in the larger scheme of things (Double vision).

- Believe that everything will work out at the end (Affirming faith).

The main difference between Cooper & McLeod’s (2010) approach and Wong’s is that the latter’s pluralistic outlook is integrative with meaning as the central organizing construct. Thus, the commonality between different approaches of psychotherapy has to do with the basic human capacity for meaning-seeking and meaning-making.

Existential Positive Interventions of Pursing Meaning

On the basis of all available research, Wong (2012a) has concluded that meaning consists of four fundamental components: Purpose, Understanding, Responsibility, and Enjoyment/Evaluation (PURE). The empirical support on the adaptive benefits of purpose, understanding (coherence), enjoyment (positive affect) is enormous (Batthyány & Russo-Netzer. 2014; Wong, 1998, 2012b).

Consistent with Frankl (1985), responsibility is recognized as a fundamental ingredient of meaning, which is often missing in meaning research and meaning-oriented PP interventions. However, there is a large literature in social-personality research bearing on the importance of responsibility in mental health and well-being. For example, responsibility is related to research on locus of control (Lefcourt, 2014), attribution of responsibility (Weiner, 1993) and self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000). In psychotherapy, there is also the emphasis on helping clients shift from blaming others and situations to assuming personal responsibility for one’s well-being and future based on the aforementioned literature on responsibility.

PURE, as a comprehensive definition of meaning, also provides a flexible framework of existential positive interventions and encourages the pursuit of meaning along any of these pathways according to the unique need of each client. Here is a typical example of how one can use the PURE framework in meaning therapy:

- Explore clients’ stated purpose and motivations for change and their preferred future without their problems,

- Help clients gain new understanding and insight of their own difficulties and stuck-ness,

- Lead clients to embrace their freedom and responsibility to implement actions based on their self-efficacy beliefs, personal strengths, and available resources, and

- Guide clients to experiment with whether their actions would bring about positive change; if not, then, they need to either modify their goals or their actions.

The exploration, insight, and implementation elements of MT are similar to what Hill, Kanazawa, et al. (2015) identify as basic skills in working with meaning in life issues as reported by experienced psychotherapists. The last point regarding behavioural experimentation is similar to what is commonly used in CBT.

From a slightly difference perspective, PURE is similar to ACT’s intervention of enhancing committed action (McCracken, 2013). Existential positive interventions cover the following steps after spiritual activation as described earlier:

- Work with the client to develop a realistic and measurable action plan.

- Empower and contract the client to carry out their commitment, one step at a time.

- Use the double-system strategy to identify and resolve difficulties (through ABCDE; see section below, “Existential Positive Interventions of Resilience”) and return to their original goal (through PURE).

- Use the double-vision strategy to link their life goal to larger life goals or some higher purposes.

Existential Positive Interventions of Resilience

On the basis of empirical research regarding meaning and resilience (Wong & Wong, 2012), the present author has identified five elements as essential in coping with adversity: Acceptance, Belief, Commitment, Discovery, and Evaluation/Enjoyment (ABCDE). Wong (2012a) explains how these functions work together to achieve resilience. Basically, this involves a journey of self-discovery, self-reflection, and self-acceptance, along with the journey of overcoming and transcending adversities and suffering.

In the ABCDE process, acceptance is an essential existential component. Acceptance of a painful emotion is never an end in its own right, but rather an overall life attitude of accepting life as it is. Unless people confront and accept the dark side of human existence, they will have difficulty experiencing healing and flourishing. Six main reasons why acceptance is an important intervention are it

- Increases our tendency to accept life in its totality,

- Increases self-compassion in spite of our limitations,

- Increases our acceptance of other imperfect human beings,

- Reduces harsh self-judgement,

- Reduces complaints about our own misfortunes, and

- Reduces fear of uncertainties and misfortunes.

An existential gratitude exercise is perhaps the best example of existential positive intervention, in contrast with gratitude exercises as usual. The emphasis is placed on cultivating gratitude by internalizing it as an essential virtue rather than practicing the gratitude exercise as a way of increasing personal hedonic feelings. For example, instead of writing about three good things, three daily blessings can be emphasized:

- Be thankful for being alive with all its opportunities for creative contributions.

- Be thankful for family members, friends, and all those who have contributed to your life.

- Be thankful for our home, the beautiful planet earth.

Such an existential gratitude exercise is not only deeper and broader than the Three Good Things Exercise or Gratitude Visit of mainstream positive intervention, but is also more relevant to people in all life circumstances and ethnic-cultural contexts. If one meditates on the above three areas daily, it will make one a better and happier person. The current author invites positive mental health professionals to compare this existential gratitude exercise of Three Blessings with any other gratitude exercise.

Further Research

Thus, a research agenda inspired by PURE and ABCDE includes the following:

- The adaptive benefits of self-transcendence based on the above Self-Transcendence Scale as well as experimental manipulations of preferring some self-sacrifice for others.

- The adaptive benefits of beliefs in the intrinsic values and meaning of life as compared to those who do not share such beliefs.

- The adaptive benefits of training grit or commitment in pursuing a worthy goal.

Over the past twenty years, the current author has given workshops on integrative meaning therapy to all kinds of mental health workers—from psychologists, mental health therapists, and counsellors, to GP psychotherapists and clinical nurses. According to their feedback, they find the general frameworks of PURE and ABCDE, as well as the evidence-based components of these frameworks, provide considerable flexibility and confidence in their clinical practices. In other words, they find these frameworks cover additional areas of classic logotherapy due to the recent progress in PP research on meaning and positive interventions.

Perspective is Everything

As Thomas Aquinas’ treatment of the will has been succinctly summarized, “The things that we love tell us what we are” (Kreeft, 2012, p. 183). In other words, the things we love and pursue reveal our true nature. According to Aquinas and Frankl, we are physical, psychological, and spiritual beings, and our truest selves, free from earthly concerns and egotistic interests, are spiritual selves, interested in the ideals of meaning, authenticity, and compassion.

Beyond one’s physical needs for pleasure and comfort (Freud) and beyond your psychological needs for power and fame (Adler), what one loves and cares deeply about reveals the hidden aspects of one’s spiritual need for meaning (Frankl). The task of logotherapy and meaning therapy is to activate the spiritual virtue of self-transcendence as the pathway to meaning.

A simple perspective change can transform one’s life for the better. Perspective change is a powerful tool for psychotherapists and coaches. What is unique in logotherapy or MT is that perspective change is fundamental to re-orienting clients from egotistic concerns of pleasure and success to the meaning-mindset of being responsible for the well-being of others and its resulting deep satisfaction.

Like ACT, meaning therapists also ask clients questions like, “What do you care about (values, personal strivings)?” “What do you really want in life?” and “What really matters?” However, existential positive interventions go beyond values clarification and the identification of personal goals; they are also designed to awaken clients’ personal responsibility for self-transcendence as described in spiritual activation (see section above, “The Value of Self-Transcendence”).

MT also emphasizes the role of values, but it goes beyond personal strivings, because it also attempts to awaken the hidden spiritual value of longing for the “self-transcendent good.” The purpose is to help one discover life’s calling and became what one was meant to be. A slight change to the self-transcendent perspective can change how one sees life and how one lives.

Furthermore, the emphasis in MT is not on flexibility per se, but on the adaption of the responsibility to be flexible in order to change from ego to logos. The advantage of this shift away from an egotistic orientation represents a basic switch from egotistic pursuits to self-transcendence.

Existential positive interventions, based on a broad and positive explanatory system regarding human nature or the human condition, can offer people infinite possibilities of meaning and hope in the midst of unavoidable suffering. They seem more realistic and relevant to most people who are struggling with the hardship and seeming absurdity of human life. It is hoped that the second wave of positive psychology (PP2.0) will devote more research on existential positive interventions as the most promising direction to develop meaning-enhancing interventions.

Summary

- Positive interventions can become more realistic and relevant to the suffering masses if they include an existential dimension, which acknowledges that suffering and anxiety are inevitable aspects of being alive.

- Existential positive interventions are based on the assumption that one is to embrace and transform the dark side of human existence in order to find authentic happiness and resilience.

- The dialectical principle works best in existential positive interventions because it aims to bring out the bright side in negative situations and prevent the dark side in positive situations. Thus, this principle is more likely to optimize positive functioning than the binary approach of only focusing on the positives.

- The PURE and ABCDE frameworks not only provide a flexible meaning-oriented intervention, but also give therapists the confidence that all the individual components in these frameworks have considerable empirical support from both positive psychology and existential psychology.

References

- Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Burns, J., Biswas-Diener, R., Kemeza, I., Nyende, P., Ashton-James, C. E., & Norton, M. I. (2013). Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 635-652. doi:10.1037/a0031578

- Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress and coping. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Batthyány, A., & Russo-Netzer, P. (Eds.). (2014). Meaning in existential and positive psychology. New York, NY: Springer.

- Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. G. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2010). Pluralistic counselling and psychotherapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687-1688. doi:10.1126/science.1150952

- Foody, M., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2013). On making people more positive and rational: The potential downsides of positive psychology interventions. In T. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 166-193). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised and updated). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1988). The will to meaning: Foundations and applications of logotherapy (Expanded ed.). New York, NY: Meridian.

- Guttman, D. (2008). Finding meaning in life, at midlife and beyond: Wisdom and spirit from logotherapy. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

- Hayes, S. C. (2013). The genuine conversation. In T. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 303-319). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Hicks, J. A., & Routledge, C. (2013). The experience of meaning in life: Classical perspectives, emerging themes, and controversies. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Hill, C. E., Kanazawa, Y., Knox, S., Schauerman, I., Loureiro, D., James, D., Carter, I., King, S., Razzak, S., Scarff, M., & Moore, J. (2015). Meaning in life in psychotherapy: The perspective of experienced psychotherapists. Psychotherapy Research, 1-16. doi:10.1080/10503307.2015.1110636

- Hill, C. E., Kline, K., Bauvan, V., Brent, T., Breslin, C., Calderon, M., Campos, C., Goncalves, S., Goss, D., Hamovitz, T., Kuo, P., Robinson, N., & Knox, S. (2015). What’s it all about? A qualitative study of meaning in life for counseling psychology doctoral students. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 28(1), 1-26, doi:10.1080/09515070.2014.965660

- Hogg, M., & Vaughan, G. (2005). Social Psychology (4th ed.). London, UK: Prentice-Hall.

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. London, UK: Routledge.

- James, W. (1902/1958). The varities of religious experience. New York, NY: New American Library.

- James, W. (2000). Pragmatism and other writings. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992/2010). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (2006). Schema-change perspectives on posttraumatic growth. In L. G. Calhoun & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice, (pp. 47-67). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Kashdan, T., & Ciarrochi, J. (Eds.) (2013). Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Kreeft, P. (2012). Socrates meets Kant: The father of philosophy meets his most influential modern child. South Bend, IN: St Augustine’s Press.

- Lefcourt, H. M. (2014). Locus of control: Current trends in theory & research. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Lukas, E. (2015). The therapist and the soul: From fate to freedom. Charlottesville, VA: Purpose Research.

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: the architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111-131. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sousa, L., & Dickerhoof, R. (2006). The costs and benefits of writing, talking, and thinking about life’s triumphs and defeats. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4), 692-708. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.692

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychology Review, 50, 370-396. doi:10.1037/h0054346

- Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. New York, NY: Wiley.

- McCracken, L. (2013). Committed action. In T. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 128-139). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Mischel, W. (1968/1996). Personality and assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Parks, A. C., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2013). Positive interventions: Past, present, and future. In T. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 140-165). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Pennebaker, J. W., & Seagal, J. D. (1999). Forming a story: The health benefits of narrative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(10), 1243-1254. Retrieved from http://poetryforpersonalpower.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/health-benefits-of-forming-a-story.pdf

- Proctor, C., & Linley, P. A. (2014). Life satisfaction in youth. In G. A. Fava & C. Ruini (Eds.), Increasing psychological well-being in clinical and educational settings (Vol. 8) (pp. 199-215). Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

- Rashid, T., Anjum, A., Chu, R., Stevanovski, S., Zanjani, A., & Lennox, C. (2014). Strength based resilience: Integrating risk and resources towards holistic well-being. In G. A. Fava & C. Ruini (Eds.), Increasing psychological well-being in clinical and educational settings (Vol. 8) (pp. 153-176). Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

- Rogers, C. D. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryff, C. D., Love, G. D., Miyamoto, Y., Markus, H. R., Curhan, K. B., Kitayama, S., Park, J., Kawakami, N., Kan, C., & Karasawa, M. (2014). Culture and the promotion of well-being in East and West: Understanding varieties of attunement to the surrounding context. In G. A. Fava & C. Ruini (Eds.), Increasing psychological well-being in clinical and educational settings (Vol. 8) (pp. 1-19). Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

- Saleebey, D. (Ed.) (2011). The strengths perspective in social work practice (6th ed.). New York, NY: Allyn & Bacon.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. American psychologist, 61(8), 774-788. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. American psychologist, 60(5), 410-421. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 73-82. doi:10.1080/17439760500510676

- Simmons, C. A., & Lehmann, P. (2013). Tools for strengths-based assessment and evaluation. New York, NY: Springer.

- Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 65, 467-487. doi:10.1002/jclp.20593

- Steger, M. F., Sheline, K., Merriman, L., & Kashdan, T. B. (2013). Using the science of meaning to invigorate values-congruent, purpose-driven action. In T. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 240-266). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2012). Pathways to personal transformation: Theoretical and empirical developments. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.) (pp. 559-572). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Weiner, B. (1993). On sin versus sickness: A theory of perceived responsibility and social motivation. American Psychologist, 48(9), 957. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.9.957

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Existential positive psychology. In S. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 361-368). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). What is existential positive psychology? International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 3, 1-10. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/what-is-existential-positive-psychology.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81. doi:10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012a). From logotherapy to meaning-centered counseling and therapy. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 619-647). New York, NY: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/documents/HQM2-chapter28.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.) (2012b). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NT: Routledge.

- Wong, P.T.P. (2012c). What is the Meaning Mindset? International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 4(1), 1-3. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Wong-2012-What-is-the-Meaning-Mindset.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). Viktor Frankl’s meaning seeking model and positive psychology. In A. Batthyány & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in existential and positive psychology (pp. 149-184). New York, NY: Springer. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/viktor-frankls-meaning-seeking-model-and-positive-psychology/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015). The meaning hypothesis of living a good life: Virtue, happiness, and meaning. Dr. Paul Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-meaning-hypothesis-of-living-a-good-life-virtue-happiness-and-meaning/

- Wong, P. T. P. (in press). The development of a new Self-Transcendence Measure based on Frankl’s concept. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Weiner, B. (1981). When people ask “Why” questions and the heuristic of attributional search. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 650-663. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/documents/when-people-ask-why-questions.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (2012). A meaning-centered approach to building youth resilience. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 585-617). New York, NY: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/documents/HQM2-chapter27.pdf

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). New York, NY: Springer.

This publication was partially supported by the research grant on Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life from the John Templeton Foundation.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.