Abstract

My long-term research interest has revolved around the central theme of the vital role of meaning in living the good life individually and collectively. The meaning hypothesis (MH) introduced here represents an overarching framework for my meaning-centered research and interventions. This paper covers five sections: (1) The empirical foundation for MH, (2) Research on the meaning mindset, (3) Self-transcendence and virtue, (4) The role of meaning in happiness and well-being, and (5) A three factor-model of MH. This summary includes some of the main findings and key hypotheses for future research.

The Empirical Basis for My Meaning Hypothesis

My first involvement in meaning research (Wong & Weiner, 1981) was to investigate spontaneous attribution. The main finding that came out from a series of studies was that people ask two kinds of attribution questions: Causal and Existential (Wong, 1991). Under negative or unexpected conditions, people more likely ask spontaneously: What is the cause of this outcome? What is the reason or purpose? This empirical research demonstrates that people have the natural capacity and tendency for meaning seeking, and initiated my meaning research from both existential and social cognition perspectives. My ground-breaking research was the large empirical research project on implicit theories of the good life (Wong, 1998). I asked hundreds of people from all walks of life to describe their own beliefs or understanding of what constituted the ideally meaningful or good life, if money were not an issue. I used the phrases “meaningful life” and “good life” interchangeably for different samples and found that the results were indistinguishable; consequently, the final analysis was based on all qualitative data. This study was important in two ways. First, it established the face validity that, at least in lay people’s minds, a meaningful life is a good life. Secondly, its finding of the eight sources of a meaningful life has been replicated by research on meaningfulness: (1) Happiness and fulfillment, (2) Achieving something worthwhile, (3) Intimacy: marriage and family, (4) Good relationship with friends and people, (5) Self-acceptance, (6) Self-transcendence or altruism, (7) Religion, and (8) Fairness or justice.

Research on the Meaning Mindset

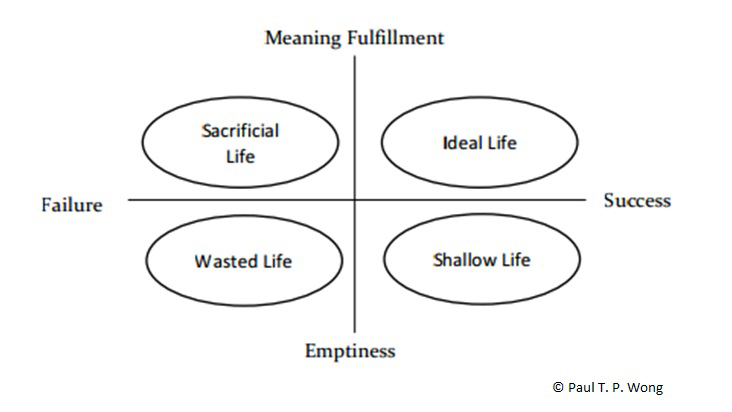

Figure 1. Meaning axis vs. Success axis.

Meaning mindset represents my second area of meaning research. Viktor Frankl (1985) emphasizes the need for a radical shift from self-focus to meaning-focus as the most promising way to lift up individuals from the dark pit of despair to a higher ground of flourishing. I have captured the relationship between Frankl’s ideas of the meaning-fulfillment and success dimensions in Figure 1. The ideal life is characterized by the successful pursuit of one’s ideals and mission. However, even in situations where one is unable to realize one’s vision—because of sickness or external circumstances—one may still feel that one has lived a worthy life because of one’s personal sacrifice for a worthy cause. All the great humanitarians, such as Albert Schweitzer, Maya Angelou, Oskar Schindler and Mahatma Gandhi, devoted their lives to a noble mission. In contrast, those who pursue fame, power and wealth can achieve only a shallow life at best; when they fail in their egotistic goals, they are more likely to become bitter, angry and depressed than those who failed in pursuing a meaningful life (Christensen, 2012; Huffington, 2013; Lyubomirsky, 2013). The practical implications for this meaning fulfillment dimension are both significant and wide-ranging. This hypothesis suggests that it is possible for individuals and society to transform meaningless strife into harmony, compassion and well-being. I have developed a Life Orientation Scale (LOS) to measure the meaning mindset. A high LOS score reflects a positive and self-transcendental mindset with strong emphasis on moral excellence and altruism. We can also predict that people who score high in LOS will be more likely to devote themselves to humanitarian relief work, social reform advocacy, or religious vocations. Such individuals are more likely to show more altruism, more eudaimonia, and more spirituality. Personally, I believe that a meaning-mindset is exactly what we need to create a culture that values social responsibility, civic virtues, and service to humanity. Ultimately, educating people with a meaning-mindset will result in a kinder and more harmonious society and more sustainable development.

Self-Transcendence and Virtue

Virtue is an indispensable dimension of the good life for individuals and society because virtue is not only good in its own right, but also benefits others. Frankl’s (1985) concept of ethical responsibility is the foundation for acting well morally and imbuing life with meaning.

Virtue as an Essential Value for the Good Life

While subjective well-being is up to each individual to decide, virtue requires a relational and objective criterion, as proposed by Aristotle. Whether a certain behaviour or certain individual is deemed virtuous is always based on some kind of social norm regarding one’s impact on other people and society. That is why virtue exists primarily in the social realm. Acting badly would not make anyone’s life worthy of living and admiration, even when one is hugely successful as a drug dealer or gangster. Aristotle’s theory of virtue ethics stands in sharp contrast to the value-neutral stance of positive psychology (Seligman, 2002). Haybron (2013) says very well, “One should not be an asshole in the pursuit of happiness” (p. 97). It is worth noting that like Aristotle, Viktor Frankl (1985) also emphasizes the need for objective values as the basis for the subjective experience of meaningfulness.

The Central Importance of Self-Transcendence

Frankl’s self-transcendence hypothesis (Wong, 2016a) is that the will to meaning is a spiritual and primary motivation for self-transcendence; thus, it predicts that spiritual pathways (e.g., spiritual care, self-transcendence) will enhance meaning in life and well-being, even when other pathways to well-being are not available. This hypothesis simply predicts that only when we redirect our focus from self-interest to something bigger than and beyond ourselves can we experience meaning in life. Frankl is unique in pinpointing self-transcendence as the hallmark of the spiritual nature and as the end state of becoming fully human, “Only when we lift ourselves into the dimension of spirit do we become fully human” (Fabry, 1994, p. 19). Thus, Frankl elevates commitment to the spiritual act of serving a higher purpose for the greater good. Self-transcendence is, by definition, intrinsically relational. Vertically, self-transcendence reaches beyond the limits of time and space, to connect with the transcendental realm or to worship and serve the Creator. Throughout his writing, Frankl has made it very clear that his concept of self-transcendence or the supra-meaning transcends specific religious views and resides in the spiritual nature of being human. Horizontally, self-transcendence transcends ego-concerns and self-interest to serve others. It is intrinsically compassionate and altruistic, given its spiritual nature. In self-transcendence, other people matter in their own right because of their intrinsic value. Loving our neighbours is its own reward. Showing kindness to strangers is its own reward. We engage in deeds of compassion and kindness because we are simply expressing our spiritual nature. This is fundamentally different from using other people as instruments for our own advancement and happiness.

The Role of Meaning in Well-Being

Snyder and Lopez (2007) are correct in proposing the formula: Happiness + Meaning = Well-being. A eudaimonic perspective of subjective well-being focuses on meaning and virtue (Ryan & Huta, 2009; Waterman, 1993). According to Ryff and Keyes (1995), psychological well-being is based on several dimensions: self-acceptance, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery, autonomy, and positive relationships with others. These dimensions cover much of the same domain as sources of meaning (Wong, 1998). I propose that meaning serves at least three important functions in maintaining positive mental health.

(1) Sources of Meaning as Contributors to Well-Being

The Personal Meaning Profile (PMP) (Wong, 1998) is related to both presence of wellbeing and absence of mental illness. Mascaro (2006) found that PMP was negatively related to depressive symptoms, depression and hopelessness, and positively related to meaning fulfillment, hope, and internal locus of control. Although all these studies are correlational, there are some perspectives and longitudinal studies which show that meaning can predict future well-being (Mascaro, 2014; Mascaro & Rosen, 2008).

(2) Meaning as a Protective/Preventive Factor

However, when people are going through very difficult times, meaning, rather than positive emotions, becomes more important in maintaining some level of well-being (Frankl, 1985; Wong, 2010; Wong, 2011). According to the meaning-centered approach to well-being, the ABCDE strategy serves the function of transforming negatives into positives, as well as making suffering more bearable. The ABCDE acronym stands for acceptance, belief, commitment, discovery, and evaluation/enjoyment. I have given a detailed account on how these components contribute to resilience and well-being in adverse situations (Wong, 2010; Wong & Wong, 2012).

(3) Meaning as the Basis for Hope in Extreme Situations

The important role of hope in maintaining one’s well-being and health has been well documented (Snyder, 2000). Hope provides the motivation to strive and improve one’s life. However, in extreme situations, such as the Holocaust or dying from incurable cancer, one needs a different kind of hope that is not based on confidence in one’s own competence or positive expectations of a good outcome. Viktor Frankl (1985) developed the concept of tragic optimism, which enabled him to survive the Nazi death camps. I have identified the key components of tragic optimism as consisting of acceptance, affirmation, faith in God, self-transcendence, and courage. Only meaning-oriented hope can survive unimaginable horrors and sufferings.

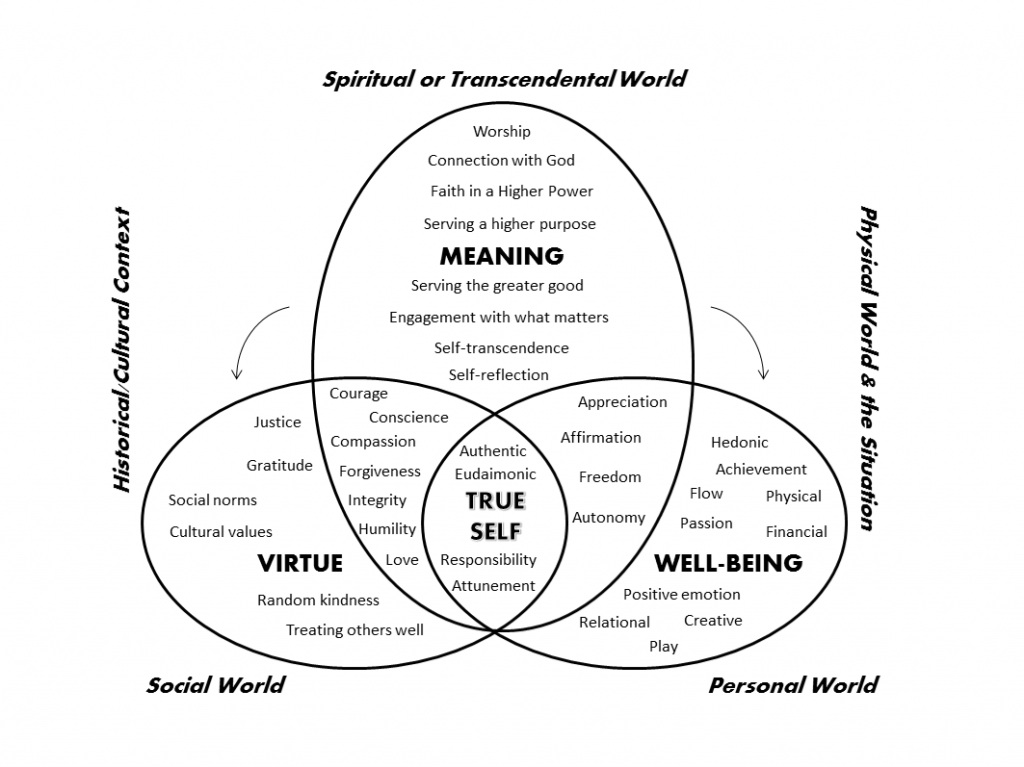

An Integrative Meaning-Hypothesis of the Good Life: Linking Meaning to Well-Being and Virtue

I have developed a three-factor model of my meaning-centered approach to a good life, as shown in Figure 2. This model clearly reflects Haybron’s (2013) influence. The main difference between Haybron and me is that I include the supernatural component as an essential part of my conceptualization of meaning. It is worth noting that Haybron started his analysis with a focus on happiness and I started my search for a good life focusing on meaning, but both of us came to the same conclusion: we accept Aristotle’s teleological view of eudaimonia and emphasize the cultivation of virtue and meaning as the foundation of happiness and well-being. Such a view recognizes both nature-fulfillment of human excellences as well as self-fulfillment of individual potentials. In this model, meaning is the key because it influences well-being and virtue. Thus, leading a meaningful life contributes both to well-being and to virtue. Well-being is broader than happiness as most people understand it, because it is concerned with what ultimately benefits a person rather than how positive one feels at any moment.

(1) Well-Being

Well-being is a broader concept than happiness. “Well-being…is ultimately a matter of value: what is good for us?” (Haybron, 2013, pp. 77-78). What ultimately benefits a person is “displaying the excellences characteristic of human beings…rooted in universals of human nature” (p. 82). Haybron’s neo-Aristotle position proposes that eudaimonia results not only from nature-fulfillment (Aristotle) but also from self-fulfillment (John Stuart Mill). The latter refers to fully developing one’s unique potential or true self.

(2) Virtue

This is another end value of a good life. A good life is not only good for the person (wellbeing), but also intrinsically good. It is a life that will pass the “death bed test” of having no regrets for one’s life. It will also pass the “eulogy test” because others can rightly praise the deceased as a good and decent human being who has treated others in a kind and admirable way. A life devoted to the pursuit of virtue represents the deepest, fullest happiness because it fulfills its unique human nature.

(3) Meaning

A good life is not just living well by acting well, but also by connecting with people and things that matter. Meaning impacts well-being not only through the route of virtue, but also through the activities of engagement and authenticity. The good thing about the meaning hypothesis is that the essentials of a good life are accessible and available to most people. According to Haybron (2013), “the essentials of a good life are available even to people who don’t own much–and even…to those who never manage to be happy” (p. 9). His essentials are in many ways similar to Metz’s (2013) fundamentals of meaning in life. He provides a very valuable road map to all those seeking a good life.

Conclusion

My research program on MH includes empirical research, theoretical formulation, and test development. My entire research program is predicated on the need for a humble science to incorporate wisdoms from humanities and other social sciences (e.g., Wong, 2016b). Such a humble approach (Templeton, 1998) will facilitate multidisciplinary collaboration and cross-fertilization for the greater good.

References

- Christensen, C. M. (2012). How will you measure your life? New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Fabry, J. B. (1994). The pursuit of meaning (new revised ed.). Abilene, TX: Institute of Logotherapy Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Haybron, D. M. (2013). Happiness: A very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Huffington, A. (2013, May 29). Beyond money and power (and stress and burnout): In search of a new definition of success [Web log post]. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/arianna-huffington/third-metric-redefiningsuccess_b_3354525.html

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). The myths of happiness: What should make you happy, but doesn’t, what shouldn’t make you happy, but does. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

- Mascaro, N. (2006). Longitudinal analysis of the relationship of existential meaning with depression and hope. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas.

- Mascaro, N. (2014). Meaning sensitive psychotherapy: Binding clinical, existential, and positive psychological perspectives. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in positive and existential psychology (pp. 269-289). New York, NY: Springer.

- Mascaro, N., & Rosen, D. H. (2008). Assessment of existential meaning and its longitudinal relations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(6), 576-599.

- Metz, T. (2013). Meaning in life. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Huta, V. (2009). Wellness as health functioning or wellness as happiness: The importance of eudaimonic thinking. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 202-204.

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719-727.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Snyder, C. R. (Ed.). (2000). Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2007). Positive psychology: The scientific and practical explorations of human strengths. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Templeton, J. (1998). The humble approach. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press.

- Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 678-691.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1991). Existential vs. causal attributions. In S. Zelen (Ed.), New models, new extensions of attribution theory (pp. 84-125). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85-99.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Meaning-seeking, self-transcendence, and well-being. In A. Batthyany (Ed.), Logotherapy and existential analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute (Vol. 1; pp. 311-322). Cham, CH: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). A decade of meaning: Past, present, and future. Journal of Constructivist Psychology. doi:10.1080/10720537.2015.1119085

- Wong, P. T. P., & Weiner, B. (1981). When people ask “Why” questions and the heuristic of attributional search. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 650-663.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (2012). A meaning-centered approach to building youth resilience. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 585-617). New York, NY: Routledge.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2015, December). The meaning hypothesis of living a good life: Virtue, happiness, and meaning. Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina. (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)