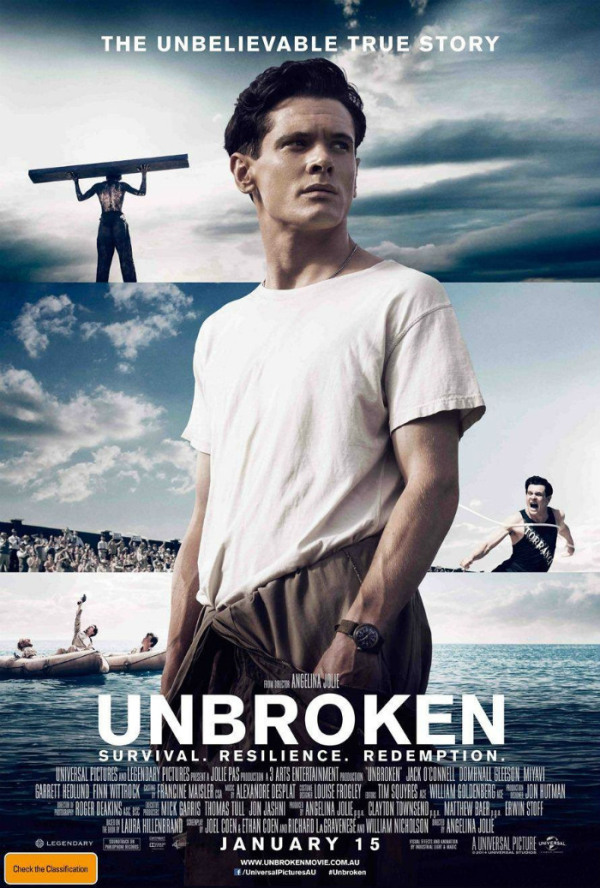

An Olympic gold runner Louie Zamperini (Jack O’Connell) enlisted and trained as a bombardier after Pearl Harbor. Most of the film revolves around how he responded to the litany of adversities after his plane was shut down. After spending 47 days adrift on a raft, he was captured by the Japanese military and interned as a POW for 27 months.

The plot is straightforward and simple: Louie suffered all kinds of traumas, but he survived through incredible fortitude and grit. Most of the footage chronicles blow by blow the various kinds of vile abuse from his antagonist Watanabe The Bird (Miyavi). The cinematic version of Louie’s ordeals is more graphic, hence more offensive to one’s sensitivity than the original book. Some of the bloody scenes of torture are very painful to watch.

What Kind of Movie is Unbroken?

This film is not the typical Hollywood products that provide entertainment and a temporary escape from reality. On the contrary, it takes you to the abyss of darkness of the human condition. The only consolation is that after suffering through many bloody scenes, one gains some insight into the deeper meaning of fortitude and grit in hellish circumstances. Angelina Jolie has succeeded in producing and directing a film that will inspire many people in their personal struggles.

A Psychobiographic Study of Grit

Another value of this biopic is that it raises many questions that stay with you long after viewing the film. What are the factors that have created an evil monster like The Bird, who delights in inflicting pain on others? Why did he single out Louie as the target for indulging his sadistic desires? What kind of moral teaching made Louie decline the Japanese offer to serve as a propaganda tool, knowing full well that the consequence was more brutal punishment? Finally, what sustains Louie’s inner fortitude?

With its realistic fighting scenes, both in the air and on the ground, and the heroism of soldiers and POWs, this film may also be remembered as one of the great wartime dramas during World War II as the classic epic The Bridge on the River Kwai.

However, to me, the greatest value of this film is that it is a psychobiographic study of grit. In its fullest sense, “grit” means the behavioral manifestation of the defiant power of the human spirit against fate, against all the natural and man-made traumas, and against all evil forces to defend what really matters. In Unbroken, what really matters is self-respect and human dignity, without which, one would be less of a human being, and life would not be worth living.

A Case Study of the Defiant Power of the Human Spirit

In many ways, this film reminds me of Viktor Frankl’s (1959/1984) classic: Man’s Search for Meaning. Both Louie and Frankl have one thing in common: when they were subjected to unimaginable horrors of sufferings and degradation, they demonstrate the defiant power of the human spirit, which enables them to transcended extreme traumas.

Based on his observations of inmates in concentration camps and patients in hospitals, Frankl (2000) concluded that the will to meaning and self-transcendence are essential for survival: “Under the same conditions, those who were oriented toward the future, toward a meaning that waited to be fulfilled—these persons were more likely to survive” (p. 97).

The defiant attitude is an essential way to maintain meaning and dignity in extreme situations. In a similar vein, Shantall (1999) reported that many holocaust survivors found relief in dwelling on such themes as religious faith and meaning to maintain their sense of human dignity and self-decency.

While Frankl drew on the principles of his logotherapy, Louie intuitively defended his pride and dignity as if he was protecting something more valuable than his own life. Louie did not have Frankl’s intellectual sophistication nor his spiritual depth to draw on. All Louie had was his defiant nature and experiences of getting out of troubles that made him what he was—a man of steel. Defiance was his second nature. Therefore, Frankl’s principle of the defiant power of the human spirit seems a plausible explanation of Louie’s extraordinary grit.

Contributing Factors of the Defiant Power of the Human Spirit

Both the biopic and the biography suggest at least four sources of his courageous stoicism and gritty fortitude.

Resilience Training in the School of Hard Knocks

Louis had a troubled childhood—an untamable wild boy, an incorrigible delinquent, a troublemaker who fought back bullies, out-maneuvered the police, and ran away from home on free train rides.

In street bawls, he was bruised, bloodied, and outnumbered, but he never backed down, never cried for mercy. In today’s educational climate, he could easily be diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder. But his strong will to defy authority, his resourcefulness to get out of any predicament, and his experience of surviving the school of hard knocks had made defiance his second nature.

His boyhood success in overcoming difficulties has bred in him an indomitable spirit and a sense of optimistic invincibility that served him well in athletic competitions and during those horrific days of captivity.

In resilience research, Ungar (2004) recognized the hidden resilience in such antisocial behaviors, Wong and Wong (2012) also emphasized the essential of behavioral resilience, which can only be learned from the actual experience of having overcome adversities. Thus, the essentials of resilience and grit were already developed in Louie’s childhood.

When he was a teenager, with the guidance and encouragement of his older brother Pete (Alex Russell), he was able to channel his willpower and passion into running and become a high school track star and an Olympic athlete. His natural ability to run as a gazelle provided a perfect opportunity to gain respect in this competitive sport. The same characteristics of grit in the sports context earned him the much-needed recognition to heal his damaged ego.

Faith in an Ultimate Rescuer

Faith in God is a recurrent theme. Looking at the clouds outside the window of his airplane, staring at the vast ocean and sky, these scenes inspired a sense of awe even without uttering a word about God.

Brought up in the Catholic faith, not exactly a practicing Catholic, his faith still sustained him in his darkest hours. His flashback of the homily of the Catholic priest “Accept the darkness, live through the night, and love thine enemies” was a source of strength and support.

While adrift on the ocean, he said to his two fellow crewmen, “Pray at night. Pray in the morning. That’s how you survive.” Under the blazing sun, tossed around in a raging sea, dying of thirst, and attacked by killing sharks, he dedicated his whole life to serving God, if he saved them. Years later, after liberation, he indeed fulfilled his vow.

To Louie, faith was more than a source of comfort and strength; it was the only glimmer of light in an otherwise menacing endless darkness. Faith in God is a key ingredient of tragic optimism, the kind of hopeless and helpless hope after devastating trauma (Wong, 2009).

Sources of Meaning in Suffering

Frankl’s concept of the defiant power of human spirit is part of his theory of meaning making. Therefore, sources of meaning make suffering more bearable and more life more livable.

His past was an important source of meaning. Meaningful moments in the past were preserved as monuments in the corridor of memories. His older brother’s advice “If you can take it, you can make it” continued to ring in his ear to reinforce his fortitude during his futile struggle in the POW camp.

When sending him off for training for the Olympics at Berlin, his brother again planted this thought: “A moment of pain is worth a lifetime of glory.” In his most painful moments, again and again, he remembered how he endured incredible pain to come from behind and win the race.

His future meaning came from dreams of running through an Olympic stadium and climbing up to the podium for a medal or thinking of seeing his mother and brother. His longing for a future meaning reminds me of Frankl’s concentration fantasy of giving lectures in an American university or being reunited with his beloved wife.

His present meaning comes from his “creative value” of creating stealing from the enemy to stay alive and creating sabotaging the enemy to restore a sense of agency. His “experiential value” of camaraderie and secret sharing of war progress with other POWs also gave him some sense of meaning in the midst of unbearable suffering. However, most of his meaning was derived from “attitudinal value” of taking a heroic defiant posture towards his tormentors. Such an attitude prevented the enemy from taking away his self-respect and dignity that enabled him to survive like a human being.

The Defiant Power of the Human Spirit

In essence, this defiant spirit is an attitude of defiance. The best example of this attitude can be found in a memorable scene, in which Louie was ordered by The Bird to hold a six-foot-long beam over his head on pain of being shot to death. With a shout and a burst of energy, he was able to hoist the heavy beam over his head. Emaciated, sickened, starved, his frail body was more like a skeleton wrapped in a yellow skin; yet, he was able to muster enough strength to stand tall, unbent, unbroken, holding a huge beam over his head for 37 minutes! In a wide-angle shot, against the sky, Louie and his shadow conjure up the image of Christ crucified.

It was a battle of the will, and the duel between two individuals, and the deadly clash between human dignity and evil monstrosity. On the one side, Louie held the beam with his angry eyes fixed on The Bird. There was something extraordinary going on inside him and sustaining him. We could almost hear him say, “You can destroy me, but you cannot defeat me. You cannot break me. You will not break me.” On the other site, we see The Bird, sitting up there, taunting and mocking Louie. We can see his face distorted with anger and surprise as Louie stared him down and defied his expectation.

Conclusion

In the psychology literature, “grit” is defined as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals.” (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007). In normal achievement-related contexts, this dual-component model works quite well, but in extreme situations, such as POW camps or concentration camps, and the pressing concern was survival rather than achievement, a third factor—the defiant power of the human spirit becomes necessary. According to Frankl (1959/1984), this defiant power refers to the human capacity to tap into the spiritual dimension in order to transcend unbearable suffering.

At the deepest level, perseverance and passion are fuelled by defiant power of the human spirit, which may be characterized by a ferocious will, an indomitable fortitude, and an exceptional capability for enduring suffering. Such a defiant attitude is at the heart of the human phenomenon of grit.

Unbroken shows that prior experience of overcoming adversity, faith in a Higher Power, the human capacity of meaning making, and the defiant attitude are main contributors to grit. In particular, this film offers valuable insight on the defiant power of the human spirit—an important principle that deserves more research attention from positive psychologists.

References

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087-1101. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

- Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (2000). Recollections: An autobiography. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Hillenbrand, L. (2010). Unbroken: A World War II story of survival, resilience, and redemption. New York, NY: Random House.

- Shantall, T. (1999). The experience of meaning in suffering among Holocaust survivors. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 39, 96-124. doi:10.1177 /0022167899393009

- Ungar, M. (2004). Nurturing hidden resilience in troubled youth. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany, & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen. (Early version available here.)

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (2012). A meaning-centered approach to building youth resilience. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 585-617). New York, NY: Routledge.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2015). The positive psychology of grit: The defiant power of the human spirit. [Review of the movie Unbroken, 2014]. PsycCRITIQUES, 60(25). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039390

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.