Stress is an inevitable aspect of living. In everyday parlance, stress refers to an emotional state of pressure, tension, or distress because of certain demands, actual or imagined, that threaten our psychological or physical well-being. These demands may involve a major transition in life, such as a promotion or divorce, or a traumatic event, such as a car accident or the death of a loved one. They may also involve everyday hassles, such as traffic jam or a toxic work environment.

Generally, coping represents an adaptive response to change or demands in life. Contrary to widespread belief, a life without any stress may not be good for us, because our minds need certain challenge and striving to feel alive, just as our muscles need to do work or exercise to stay healthy. Imagine a life of endless pleasures, free from work and worries. Sooner or later, boredom will set in. A pleasant life without purpose and meaningful engagement may not be much of a life.

A positive way to look at stress is to consider it a friend or someone who challenges us to stretch ourselves and grow. Stress is bad for us (distress) only when it is intense, chronic, and beyond our ability to manage. Stress is good for us (eustress) when we are able to harness it into a source of positive motivation to make creative and constructive changes, resulting in increased well-being for the self and society. This entry provides a history of the evolution of coping with a focus on effective coping and eustress.

Early Biological Theories

Stress researchers in the early and mid-20th century were biologists who focused on subcortical physiological coping responses. Sir Walter Cannon’s homeostasis thesis was based on observation of animals’ fight-or-flight instinctual response to threat. During stressful encounters, animals’ biological systems were mobilized to deal with the emergency. Such a stress reaction may be beneficial for immediate survival, but with chronic stress, it may have adverse effects on health as Hans Selye discovered later.

Selye, an endocrinologist, postulated the nonspecific general adaptation syndrome in coping with both negative stress (distress) and positive stress (eustress). The body responds to each type of stress in similar ways. At first, we go through the same alarm reaction stage, followed by the resistance stage; finally, after prolonged exposure to stress, a pathological state of exhaustion sets in. Chronic stress is not good for us because our stress hormone, corticosteroid, can compromise our immune system, making us more susceptible to infectious illness and cardiovascular disease.

According to Selye, eustress refers to a pleasant type of stress, such as a passionate kiss or a promotion. It may also refer to a positive response to the stressor, such as mobilizing our biological resources to manage the stress without reaching the state of exhaustion or burnout. Distress, on the other hand, is accompanied by negative emotional states of pressure, tension and anxiety, typically, when we find the stress overwhelming or prolonged. Ideally, we can experience stress without distress.

Cognitive-Relational Theory

The first psychologist to develop a cognitive theory of stress and coping was Richard Lazarus; he capitalized on the executive function of the neocortex. The seminal book on stress and coping Stress, Appraisal and Coping by Lazarus and Susan Folkman has dominated the field of stress research since its publication in 1984. Their theory is based on cognitive and relational processes, and is known as cognitive-relational theory. Stress is defined as a relationship between the person and the environment; stress is experienced only when it is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and as endangering his or her well-being. Coping is defined as conscious cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage the internal and/or external demands during a stressful transaction.

From this transactional perspective, eustress is not defined by the nature of the stressor, but by the nature of the cognitive response. Eustress is experienced when a stress is appraised as “challenging” and desirable rather than “threatening” and undesirable. To the extent that the stress is perceived as manageable, one may respond with a sense of vigor, meaning, and optimism.

The Ways of Coping questionnaire, developed by Folkman and Lazarus, was designed to measure two functionally different broad coping categories. Problem-focused coping consists of various instrumental strategies, whereas emotion-focused coping includes Sigmund Freud’s defense mechanisms and other types of cognitive strategies. Most of the research literature on stress and coping has been limited to these two types of coping.

Appraisal plays a key role in the coping process. According to Lazarus, primary appraisal of a threat or challenge leads to secondary appraisal of coping resources and options. Secondary appraisal processes such relevant information as, What kind of problem is it? What can be done about it? Is it within my control? Actual coping behavior depends on secondary appraisal.

In 1990, Edward Peacock and Paul T. P. Wong developed the Stress Appraisal Measures (SAM) on the basis of cognitive-relational theory. It measures three primary dimensions: threat, challenge, and centrality. Challenge reflects anticipation of personal gain or growth, while threat implies harm or loss. Whether a person experiences emotional distress depends on whether an event is appraised as a challenge or threat. Centrality refers to the perceived importance or significance of any event with respect to one’s well-being.

The three secondary appraisal measures consist of three types of controllability: controllable by self, controllable by others, and uncontrollable by anyone. SAM also includes an overall stressfulness measure. There is evidence that different appraisals lead to different patterns of coping. For example, controllable stressors lead to problem-focused coping, whereas a stressor appraised as controllable by others leads to help seeking.

Resource-Congruence Model

The resource-congruence model, developed by Wong and colleagues in 2006, goes beyond cognitive psychology to embrace humanistic-existential psychology and cross-cultural psychology. In many ways, it is a comprehensive model of coping because it substantially expands our understandings of stress, coping, and inner resources. It rejects the long-held notion that some coping mechanisms are inherently pathological, while some are inherently adaptive. Instead, it hypothesizes that coping effectiveness hinges on having enough appropriate coping resources and employing coping strategies that are congruent with the nature of the stress as well as the cultural context.

An Expanded Repertoire of Coping Responses

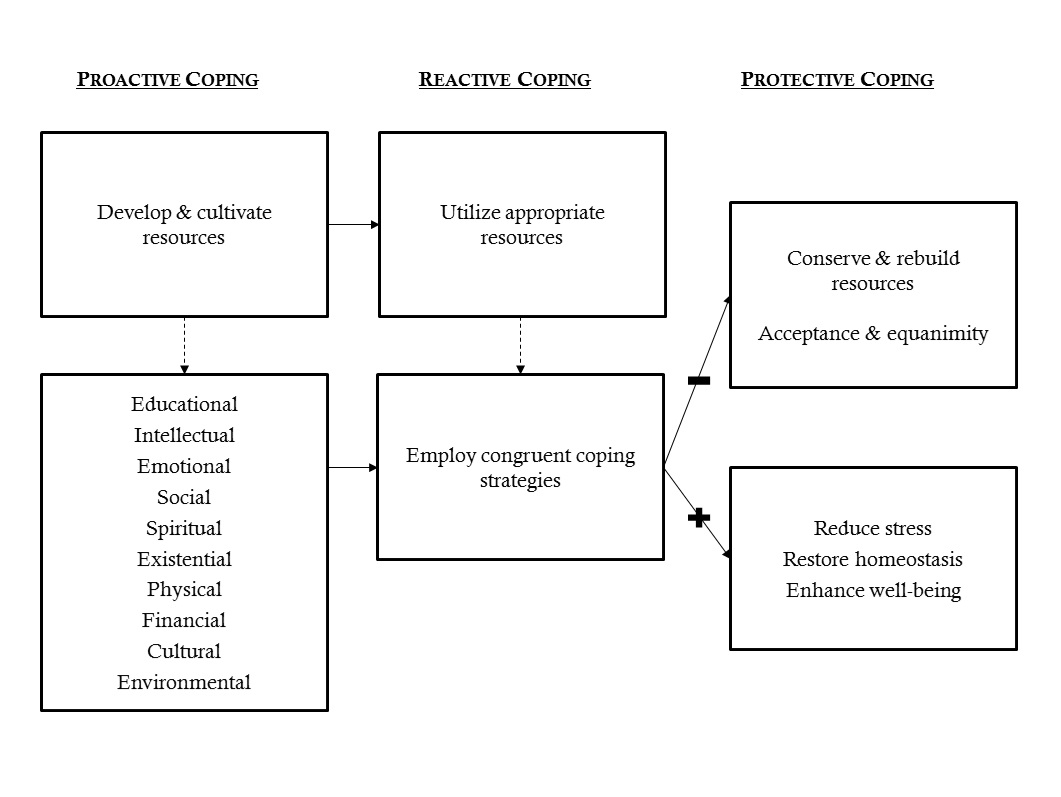

An important addition to the traditional coping repertoire is the proactive or creative coping category as shown in Figure 1. Because stress is experienced when the demand exceeds coping resources, it stands to reason that we should be engaged in developing or cultivating various kinds of coping resources if we want to reduce the likelihood or level of stress. Acquiring more education to stretch one’s intellect or acquire more marketable skills would be a proactive way to cope with the prospect of unemployment.

Figure 1. A Schematic Presentation of the Resource-Congruence Model of Effective Coping

Reactive coping begins as soon as a problematic condition is appraised. At this stage, two types of congruence are important for effective coping. First, appraisal should accurately reflect reality and be based on an objective, rational assessment of the demands and available resources. Second, the strategies selected need to be congruent with the nature of the stressor and the cultural context. For example, what works in one’s original country may no longer work in the host country.

When reactive coping is not successful because of lack of resources or congruence, one needs to switch to protective coping to conserve energy; in this stage, to accept what cannot be changed would be an effective way of coping. Acceptance as an important coping strategy has gained recognition due to the popularity of mindful meditation.

According to this model, both failure and success in reactive coping can lead to beneficial outcomes for the individual. In the case of coping failure, individuals learn the lesson of acceptance with equanimity. In the case of coping success, they are able to reduce the stress, restore a sense of well-being and move on with renewed confidence and energy.

After years of research, Wong and associates developed a reliable and valid Revised Coping Schema Inventory (Revised CSI), consisting of nine coping categories:

- Situational—similar to problem-focused coping

- Passive emotional—similar to emotion-focused coping

- Social support—seeking tangible help from friend and experts

- Active emotional—similar to seeking emotional support

- Self-restructuring—changing attitude or behavior to suit the situation

- Meaning—similar to meaning-focused coping

- Tension reduction—practicing relaxation and medication

- Acceptance—accepting what cannot be changed

- Religious—seeking help from God or a higher power

The first four categories are similar to but broader than Folkman and Lazarus’s Ways of Coping. The additional five categories have received the least research attention, but they form the basis for the last stage of the evolution of coping—personal development and transformation.

Sources of Stress

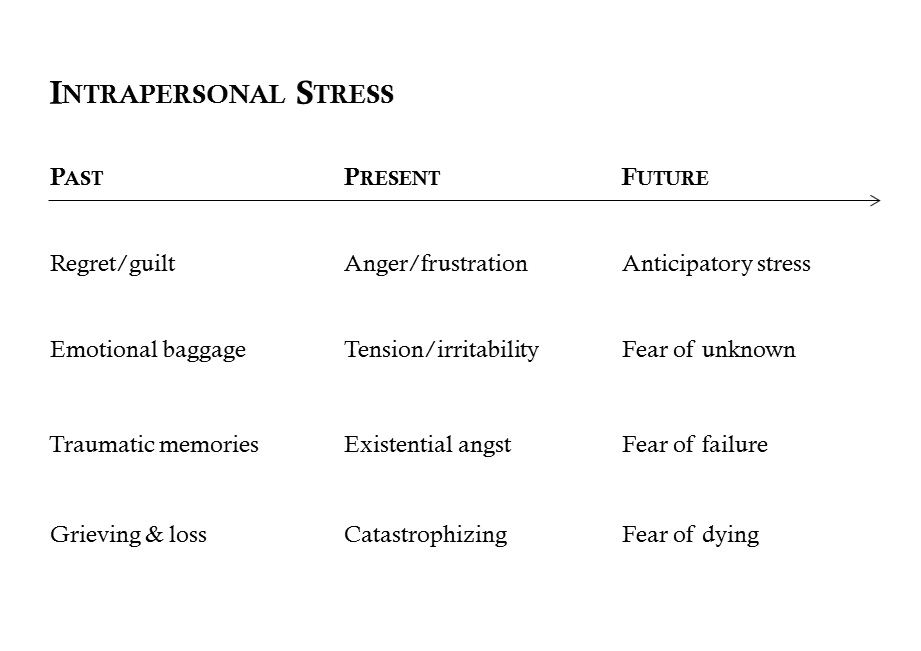

A stressor is often thought of as something external happening to a person. However, one can experience internally generated stress, as shown in Figure 2. When a person regrets his or her past, complains about the present, and fears the future, such a person would be under a great deal of stress even without any external stressor. In a very negative frame of mind, a person may react to a trivial negative event as if it were a crisis.

Figure 2. Types of Intrapersonal Stressors Along the Temporal Dimension

Figure 2. Types of Intrapersonal Stressors Along the Temporal Dimension

What would be the appropriate coping responses to various kinds of intrapersonal stress? From the perspective of the resource-congruence model, problem-focused coping would not be appropriate, and emotion-focused coping would not be adequate because the distress is self-inflicted. Cultivating an appreciative attitude toward life may be a good start to reduce a lot of distress. Similarly, meaning-based coping and acceptance would be helpful, because whatever the problem, it would be more bearable if the person is able to discover the meaning in suffering and accept what cannot be changed. There is now a growing literature on the adaptive benefits of meaning reconstruction, acceptance, and religious faith in coping with stressors beyond human control.

The model also recognizes societal stressors, which are defined as stressful living conditions that affect large segments of the population. Such stress may be caused by natural disasters, terrorism, war, pandemics, famine, or a brutal, oppressive government. Recent examples include the 2004 Asian tsunami and the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa. However, both the resource-congruence model and common sense dictate that collective coping would be of primary importance in dealing with large-scale disasters. Community services offered by nongovernmental organizations, such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army, government emergency relief efforts, and international aid are needed to ensure personal safety and meet basic survival needs of the victims. It stands to reason that when there is a societal problem that requires collective wisdom and resources, people need to find a way to work together to resolve it.

Advantages of the Resource-Congruence Model

The resource-congruence model provides a comprehensive approach to stress management. It goes beyond traditional concerns with reactive coping and emphasizes proactive measures. This new emphasis on the cultivation of coping resources can reduce the likelihood of feeling overtaxed and stressed out.

Another contribution of the model is that it recognizes the role of cultural knowledge. Acculturation stress is a distinct source of stress for new immigrants and foreign students. Thus, cultural knowledge of both the stressors and appropriate coping responses is necessary to improve coping efficacy.

Finally, this model capitalizes on the human capacities of rational thinking, meaning making, and spirituality/religiosity. It takes rational thinking to realistically appraise the situation and select appropriate strategies. The capacity of meaning making can transform tragedies into triumphs, as emphasized by Viktor Frankl and Wong. The adaptive values of spirituality and religion have been well documented by Kenneth Pargament and others.

Coping as Personal Transformation

The last stage of the evolution of coping may be called personal transformation. This stage reflects the influence of humanistic-existential psychology, as characterized by the work of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, who emphasize human beings’ growth potential and self-actualization. This holistic focus on personal development also reflects Frankl’s teaching on self-transcendence through the will to meaning. This latest development is built on the last five coping strategies of the Revised CSI, but reframed as a holistic and meaning-centered approach to personal development. Viewed this way, coping is no longer an attempt to develop specific resources and to employ appropriate coping responses; coping becomes a way of life, a lifelong process of learning and personal development. This amounts to constantly developing one’s psychological immune system so that it becomes increasingly more resistant to stress or more tolerant of stress.

Personal growth and transformation are more effective than specific coping because when one is highly transformed, one has achieved such a high level of wisdom and emotional maturity so that one is at peace with oneself, with others, and with the world. Such a fully functioning person would be attuned to the totality of life and immune to most kinds of stress that would trouble others. Examples of such individuals include Lao Tze, the founder of Taoism; the current Dalai Lama, Buddhist monk and spiritual leader of Tibet, and Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The pathways may differ for these individuals, but in essence, they all involve the same processes of spiritual awakening, self-awareness of their true nature, cultivating inner goodness and compassion, and the constant discipline and practice of noble ideals and wisdoms.

The process of personal development is a lifelong process of personal discovery and improvement, because there is no end to higher learning and no limit to such personal growth. In other words, the highest form of coping is personal development and transformation, which results in becoming our best selves in order to benefit and uplift those around us.

Milestones in Our Understanding of Coping With Stress

Coping with stress is a universal process, because human survival depends on successful adaptation to stress. A brief history of coping, as presented in this entry, indicates three significant milestones in our understanding of coping with stress.

From Reactive to Proactive Coping

Proactive coping involves developing resources through the process of (1) learning from experience; (2) making friends, networking, developing love relationship, and building communities; and (3) increasing psychological capitals, such as education, emotional intelligence, and faith. Proactive coping is creative, is constructive, and serves multiple purposes.

From Instrumental to Transformational Coping

The most widely used coping strategy is instrumental coping. However, when problems are chronic, pervasive, overwhelming and uncontrollable, we need to transform ourselves in order to transcend the adverse circumstances and develop a high level of stress tolerance. As a result, we no longer fear stress, but embrace it as a necessary companion of life to challenge us along the way.

From Individual to Collective Coping

Focusing only on the solo coping efforts of individuals will not make much progress in understanding the coping patterns of collectivistic cultures, nor in effectively addressing societal problems. The history of human survival attests to the importance and power of collective coping. Individuals and groups working together in harmony to improve the human condition may be the highest form of evolution of adaptation.

See also Acceptance; Anxiety Sensitivity; Stress Appraisal; Stress; Spirituality/Religion and Health; Anxiety and Stress

Further Readings

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Kabat-Zinn, J., & Hanh, T. N. (2009). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Random House.

- Lazarus, R. S. & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Pargament, K. I. (2001). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1990). The Stress Appraisal Measure (SAM): A multidimensional approach to cognitive appraisal. Stress Medicine, 6, 227-236.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P., Reker, G. T. & Peacock, E. (2006). The resource-congruence model of coping and the development of the Coping Schema Inventory. In P. T. P. Wong, & L. C. J., Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 223-283). New York, NY: Springer.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2017). Coping and stress. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 886-890). New York, NY: Sage.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.