Authors

Co-authored with Victoria Bowers, Ph.D. candidate, Saybrook University.

Abstract

The starting point in the wellbeing research of this chapter is that life is full of sufferings, just as the living environment is full of bacteria, viruses, and toxins. Therefore, a realistic strategy to research sustainable happiness needs to include at least two components: (1) the capacity to overcome or live with suffering and stress, as measured by a comprehensive misery index, and (2) the process to achieve mature happiness and flourishing despite the dark side of human existence. This two-pronged approach is based on the second wave of positive psychology (PP 2.0; Wong, 2011). At the broadest level, wellbeing research needs to be situated in the context of universal human suffering, while a middle level of theorizing needs to specify the special circumstances and people. Furthermore, a complete theory needs to integrate the best evidence and wisdom from both the East and West. Mature or noetic happiness is characterized by a sense of acceptance, inner serenity, harmony, contentment, and being at peace with self, others, and the world.

Keywords: suffering; adversity; wellbeing; spirituality; existential psychology; second wave positive psychology; flourish; mature happiness

We appreciate the critical feedback from Dr. Marié Wissing to an earlier draft.

“The wound is the place where light enters you.” — Rumi

There are numerous human experiences that are outside the scope of current wellbeing research. Here are two examples of the first author Paul Wong’s own hospital experiences in the past. The first is from his posting on his Facebook

What kind of good life can one experience while confined in a hospital bed, suffering from all sorts of discomfort and pain? I am sorry that it is not the kind of good life described by Marty Seligman & Co. It is not based on positive feelings, engagement, achievement, or any creature comfort. I feel that the world has abandoned me in a dark pit with people who are moaning and groaning.

While alone, surrounded by darkness, anxiety, and fear, I have discovered a spiritual or transcendent kind of good life, based on the wisdom of understanding the finitude of life, the humility of letting go, the spirit of repentance and forgiveness, the attitude of loving-kindness to all, and bearing the fruit of righteousness.

I am surprised that positive psychology knows so little about the kind of good life described in James 3:13-17 and experienced by those who have to cope with suffering and dying 24/7.

In another painful experience of emergency hospitalization, Wong (2008) documented his struggle of finding happiness in a “noxious” world, describing in detail a different kind of happiness:

On really bad days—which will come to all of us sooner or later—we need something higher and something deeper to get us through; we need a different kind of happiness in extremely trying circumstances. Happiness in the noxious world is predicated on the human capacity to transcend and transform negative experiences

Unfortunately, scientific research on happiness has primarily focused on the pleasant life (hedonic

The Need for Research on Mature Happiness

There are reasons to believe that there is a third type of happiness, which has been variably described as deep happiness (Delle Fave et al., 2016), charismatic happiness (Wong, 2011), mature happiness (Wong, 2017a), and attunement-based happiness (Haybron, 2013; Wong, 2014). According to Wong (2014), attunement is a positive mental state, characterized by a sense of contentment with life and being at peace with oneself and the world. It is similar to Haybron’s concept of attunement, Siegel’s (2007) mindfulness-based attunement, and Wong’s (2012) resting mental state characterized by mindful awareness.

This type of happiness can be best described as “mature” or “noetic” happiness because it is a positive mental state of inner serenity, harmony, and

Research on mindfulness has shown that attunement-based happiness is less affected by fleeting moods or circumstances. Take, for example, when one has developed the skills of mindful meditation through Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (see Lehrhaupt & Meibert, 2017) or Itai Ivtzan’s Mindfulness-Based Flourishing Programme (see School of Positive Transformation, 2017). Mindfulness programs such as these can train people to maintain a calm mental state, less affected by fleeting emotions or situational stress.

In this chapter, we argue that research on mature happiness is needed for two main reasons. Firstly, while science has demonstrated the value of happiness, our obsession with the pursuit of happiness as the end goal may actually result in our unhappiness (David, 2016) and even make us anxious nervous wrecks (Schumaker, 2007; Whippman, 2016). Frankl (1985) long recognized that one should pursue meaning rather than happiness because true happiness is a byproduct of seeking meaning; the same argument has also been made by Emily Smith (2017). Mature happiness comes from learning how to live a meaningful life and maintain inner harmony regardless of the circumstances.

Secondly, we argue that contemporary society can be described by the opening line of Dicken’s A Tale of Two Cities:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.

On one hand, we have positive psychologists living in affluence and singing the happy song that life is good (Fredrickson, 2009; Seligman, 2011) and the future looks bright (Norberg, 2017). On the other hand, life is hard for many people, especially in certain parts of the world, like those devastated by armed conflicts and the massive exodus of refugees. Shocking images of the Rohingya (Thompson, 2017) and Syrian refugees (Bixler & Martinez, 2016) make us wonder how people can be so cruel to fellow human beings and how those deeply wounded by war and persecution think about life.

Recently, Graham (2017) has documented that happiness is not equally available to all Americans, due to increasing income inequality and widening gaps in hopes and aspirations. Graham draws on cutting-edge research linking income inequality with

In addition, we also need to consider additional objective indexes that indicate the human costs of progress and the general malaise in contemporary society. First of all, climate change is threatening human existence (Johnson, 2017), and pollution poses serious health risks and claims millions of lives in China (Yan, 2017) and India (Ani, 2016). In North America, there is a crisis of drug addiction, and deaths due to opioid overdose have increased dramatically in recent years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). In addition, depression has increased by 18% in the last decade (Thompson Reuters, 2017) and the suicide rate has reached a 30-year high in the U.S. (Tavernise, 2016). Finally, the current “political climate” in America is stressful; many in the country are stressed by the economy (44%), gun violence (31%), and terrorism (34%) (Shamus, 2017).

If we consider all the indicators relevant to wellbeing as well as all the human tragedies around us, only the most determined Pollyannas will turn a blind eye to human miseries. Such unrealistic optimism is not only intellectually dishonest but also emotionally callous. Awareness of human suffering in no way implies sitting back and becoming helpless. On the contrary, embracing suffering most likely enables us to become courageous and disciplined in our quest for a better world.

The Imperative of Existential Courage

According to McMahon (2017), author of Happiness: A History, the prevailing view down through history in all countries was that life is hard and full of suffering. Thus, people’s primary concern was how to best survive rather

Most religions and philosophies suggested that the best way to deal with suffering was to look it in the eye. Yet what all of these traditions shared was the belief that suffering, though pervasive, could be overcome through discipline and sacrifice.

An oft-cited quote from Helen Keller (1903) is this, “Although the world is full of suffering, it is also full of the overcoming of it.” Similarly, Edwin Hubbell Chapin observed, “Out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls; the most massive characters are seamed with scars” (as quoted in Gilbert, 1895, p. 567). These quotes reinforce McMahon’s argument for “discipline and sacrifice” in order to overcome suffering and make life better.

“There is a vast difference between positive thinking and existential courage,” said Barbara Ehrenreich (2009, p. 6). Positive thinking is often based on positive bias or illusion, whereas existential courage demands that we confront the dark reality and discover a mature happiness in spite of suffering.

Maddi (2004) was the first psychologist to operationally define existential courage in terms of hardiness, which consists of the attitude of commitment (vs. alienation), control (vs. powerlessness), and challenge (vs. security). Later, he also demonstrated that hardiness can be measured and trained to increase existential courage (Maddi, 2013). May (1975) pointed out that existential courage is the courage “necessary to make being and becoming possible” (p. 4).

Life is inherently stressful and difficult. Growing up, we can all relate to the following kinds of existential courage, including the courage to grow up in the face of an uncertain future and confusing demands; the courage to live in the face of inevitable sufferings, such as sickness, loss, or death; the courage to pursue your dreams or life goals despite obstacles, risks, and failures; and the courage to do the right thing and stand up for your values in the face of threats and real dangers.

When people mature psychologically or spiritually, they will have the courage and wisdom to discover mature happiness. When they give up the illusion and expectation that the world owes them happiness, and when their mind is armed with courage to confront and overcome suffering, injustice, and death, then nothing in the world can rob them of their inner peace. Furthermore, by focusing their minds on something good and meaningful, they will be able to experience mature happiness in spite of the messy condition they are in.

This kind of happiness may be also referred to as noetic happiness because it involves an existential/spiritual dimension. An abiding sense of inner harmony, contentment, and

The Pivotal Role of Meaning

When people go through very difficult times, meaning, rather than positive

In addition to being a protective factor, meaning also serves as new grounds for hope in hopeless situations (Wong, 2009a). The pursuit of meaning is always future-oriented; it motivates people to strive towards a worthy goal. Even in extreme situations, such as the Holocaust or dying from incurable cancer, one can still discover meaning.

According to the meaning hypothesis of the good life (Wong, 2015), leading a meaning-centered life contributes to both happiness and virtue. The spiritual dimension of meaning enables us to become fully functioning ethical human beings and have the courage to transcend all the limitations of this life. This is probably due to the increasing realization of the need to embrace the dark side of human existence as the natural context for psychological wellbeing, just as medical science needs to embrace the dangerous environment of bacteria, viruses, and toxins as the context for physical health. Research on tragic optimism illustrates that the existential perspective is the way to “show how positive psychological approaches can speak to both trauma and suffering…and existential issues” (Linley, Joseph, Harrington, & Wood, 2007, p. 12).

It is deeply gratifying that, in the past few years, existential positive psychology (Wong, 2001, 2009b) has gained more recognition from both the positive psychology circle (Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2016; Tran, 2014; Wong, 2011) and the humanistic-existential community (Batthyány & Russo-Netzer, 2014; Batthyány, Russo-Netzer, & Schulenberg, 2016; Wong, 2017b).

Mature Happiness and Meaning in Suffering

Wong’s (2017a) latest thinking on the scientific research of mature happiness emphasizes the importance of the contextual principle of

When suffering is inevitable and beyond our control, we can overcome and transform it into strength and joy through cultivating our spiritual and existential capability. This line of research focuses on four major strategies: (1) effective coping (Wong, 1993, 2017e); (2) existential courage and mental toughness or grit (Wong, 2014b, 2017f); (3) the vital role of meaning in wellbeing (Wong, 2012a, 2014c; Wong & Fry, 1998); and (4) working towards a compassionate and virtuous society through life education and good work (Wong, 2017g; Wong, Ivtzan, & Lomas, 2017; Wong & Page, 2003; Wong & Reilly, 2017).

Meaning-focused coping with suffering is especially valuable. This category includes re-appraisal, reframing problems into larger meaningful situations, tragic optimism, and existentially-oriented ABCDE coping (acceptance, belief, commitment, discovery, and enjoyment/evaluation) (Wong, 2012b).

Thus, we need a new model for flourishing in suffering. This model consists of six components, each representing a different virtue or attitude: courage, acceptance, self-transcendence, meaning, appreciation, and compassion (CasMac). This model complements Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model, which posits that wellbeing depends on positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and acceptance. It is predicted that CasMac is more relevant in adversities, while PERMA is more relevant in peace and prosperity.

Finally, Wong argues that mature happiness will complement hedonic and eudaimonic

It is high time to empirically investigate this calm-oriented wellbeing experienced and sought after by millions of people in Asia. Wong believes that mature happiness is also relevant to suffering individuals in the West. Here is Wong’s Mature Happiness Scale:

Considering your life overall, please characterize your life by rating the following statements using the scale (from 1 to 5) below, with 1 being “not at all,” 3 being “often,” and 5 being “all of the time.”

- I am able to maintain inner peace.

- I feel comfortable in my own skin.

- I have learned to accept life as it is.

- I am troubled by inner conflict.

- I am at peace with myself.

- I have learned to remain calm, whatever comes.

- My conscience bothers me.

- I have learned to be content in every situation.

- I am able to give thanks at all times.

- I am able to live in harmony with people that matter to me.

- I am worried about my future.

- I have learned to let go of all my cares and burdens.

(Note that the following items are scored negatively: 4, 7, 11)

Conceptions of Mature Happiness According to Eastern Philosophy

Philosophies of the East and West together lead to a greater understanding of happiness. While eudaimonic happiness is primarily based on Aristotle’s philosophy, mature happiness is primarily based on Eastern philosophy and transpersonal psychological theory, which focus on attunement.

Buddhist Psychology

Buddhist psychology emphasizes the importance of cultivating wisdom and compassion in order to be free from suffering and enjoy peace and contentment (Kornfield, 2008). Mature happiness allows a person to have a comfortable intimacy with themselves, a confident openness to new experiences, feelings of competence, and even mastery of their own mind (Hanson, 2013). Even in hard times, peace, contentment, love, and happiness can be found through appreciating the good elements of life and engaging life’s challenges with wisdom, courage, and compassion. Happiness can be cultivated by activating positive states of mind such as strength, peace, calm, love, or gladness even in the midst of hardships.

Although we all seek happiness and try to avoid pain and suffering, Buddhism points out that suffering comes from craving happiness and the aversion of pain; both of these psychological mechanisms are rooted in primordial ignorance and delusion about life (Chen, 2006). Having a clear vision of reality allows us not to be attached to transient things for happiness and illuminates the good times from the bad times.

Buddhism emphasizes that the pursuit of happiness involves the two-pronged approach, which includes both efforts to be liberated from suffering and efforts to cultivate happiness; these two efforts are intertwined (Dhiman, 2008; Kwee, 2012; Rahula, 1974). Awakening involves the daily spiritual practice of Dharma. His Holiness the Dalai Lama said, “The practice of Dharma is a constant battle within, replacing previous negative conditioning or habituation with new positive conditioning” (Dalai Lama & Cutler, 1998, p. 43).

The Buddha conceptualized that our minds are the main source of our own fulfillment and happiness as well as our unhappiness and despair (Gilbert, 2009; Gilbert & Choden, 2014). Therefore, learning to find the meaning in suffering can be achieved through cultivating mindfulness, meaningfulness, and integrating compassion towards self and others. From the day of our birth until we die, relationships play the most vital role in our happiness and wellbeing because they give us access to affiliation and loving-kindness. Mature happiness can be found through mindful compassion, where we learn to balance our minds and relate well to ourselves and others.

Sustained happiness from the Buddhist perspective demands sustained spiritual discipline. Matthieu Ricard, recognized by scientists as the happiest man on earth, has revealed that his secret is to reorient away from self-interest to cultivating compassion towards others (Shontell, 2016). Ricard (2007) has also described meditative exercises that result in a deep state of

Chinese Philosophies

The flourishing of classic Chinese philosophy began during the Spring and Autumn Period (722-481 BC) of the breakdown of the Zhou dynasty and annexations by

Taoism was founded by Lao Tze and elaborated by Zhung Tze. The word Tao literally means “the way”—the ultimate creative principle that gives birth to the universe and nourishes everything in the cosmos. Taoism advocates the

One of the profound insights of Lao Tze is that all things in nature exist in duality or polarity. The two opposites complement each other and make the existence of each other possible. Goodness does not exist without evil. Happiness does not exist without unhappiness. Lao Tze observed, “Fortune owes its existence to misfortune, and misfortune is hidden in fortune” (as quoted in Chen, 2006, p. 92).

Related to duality is the ubiquitous pattern of change. Things in nature are cyclical—day and night, change of seasons, life and death, and so on. Everything reverses to its opposite; reversals of fortune are the way of nature. Therefore, we should not be overjoyed when times are good or be depressed when times are bad. To know the principles of duality and change is the key to adapting effectively to the vicissitudes of life. The wisdom of being flexible and accepting setbacks enables one to takes things in stride.

Taoism teaches contentment as a natural way of life. Craving for happiness and success leads to moral depravity and personal destruction, while contentment leads to happiness and health. Contentment involves overcoming cravings when times are good and overcoming worries when times are bad; thus, contentment is always there regardless of reversals of fortune. Contentment leads to humble, selfless devotion to the wellbeing of humanity.

Following the natural way of life also means learning the wisdom of “wu

If we learn to let go of our striving and craving, things will take care of themselves. We must surrender our own impulse to strive and control and allow nature to take its course, learning acceptance and stopping our own interference. The art of “do nothing” comes from meditation and learning the wisdom of the way. Learning the way is the ultimate guarantee of happiness and contentment.

In sum, Taoism teaches us that, in truth, action and passivity are one and the same, and life and yourself are one and the same being (Watts, 1940). Watts highlights that mature happiness comes from becoming what we are; “the discovery of this kind of happiness is perhaps the chief desire of man, though it is not always expressed quite in that way” (p. 17). From a Taoist perspective, the universe is viewed as an organism with continuity that is whole, dynamic, and open to change and development. In this self-generating process, the universe also has incredible unity of both matter and spirit. The two realms of matter and spirit will always exist as one, known as chi.

Confucianism is most responsible for shaping Chinese culture. Witnessing the decay of social order and the escalation of wars, Confucius sought to realize the ideal of social stability and world peace through the cultivation of individual virtues. Confucius taught that educated gentlemen should practice the following five virtues in order to live a happy and harmonious life: Ren (benevolence), Yi (righteousness), Li (propriety), Zhi (wisdom), and Xin (integrity). In sum, the good life consists of finding one’s proper place in society and dutifully performing one’s role according to the above five cardinal virtues. Such emphasis on collectivism may have been responsible for holding the country together throughout its long history.

Confucius believed that human beings are individuals in a relationship with the universe whose sole purpose is to maintain harmony. This belief fosters a deeper rhythm with nature and society. For these philosophies, mature happiness entails becoming a custodian of the earth and being in conformity with the cosmic rhythms of the universe.

In relation to mature happiness, Confucius ranks delight first, loving second, and knowing third (Pinto, 2014). The psyche experiences these

Chinese Indigenous Psychology

In Chinese indigenous psychology, group harmony is considered more important than individual success, and contentment is the key to lasting happiness. The ideal life, according to the average Chinese person down through the years, is to live simply, in peace and harmony with family members and neighbors (Wong, 2016a).

K. Yang (1988) and Ho (1996, 1998) identified the Confucius value of filial piety as the foundation for virtue, well-being, and social harmony in China. Hwang’s (2012) research on Confucian relationalism captures the essence of the relational self and ethical responsibility in the Chinese mentality.

Sundararajan (2014), another leader in indigenous psychology, critiques American positive psychology from a Confucian perspective. She argues that, in the Chinese cultural context, negative emotions can serve as a motivational force toward the enhancement of empathy and the pursuit of virtue. Thus, in certain situations, reflection on one’s negative emotions can result in more positive outcomes than focusing only on positive emotions.

Wong (2017c) has proposed that the framework of second wave positive psychology (PP 2.0) is better able to achieve mature happiness than positive psychology as usual (PP 1.0). Wong has also put forward that the following attitudes and values represented by the acronym CasMac are necessary to create mature happiness and a society of justice and compassion.

In this CasMac model, courage plays a key role

Dialectical Mandala Model of Mature Happiness

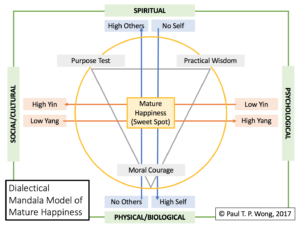

Finally, Wong presents the dialectical mandala model of mature happiness, which is based on the dialectical interactions between yin-yang and self-others. This model is more flexible than the binary model (Hwang, 2011; Shiah, 2016). The present model allows an individual to benefit self and others simultaneously, as in the case of self-transcendence, depending on the context. Self and others are viewed as two sides of the same coin. Similarly, the model also allows an individual to be both high in yin and yang, as in the case of accepting the bleak reality yet continuing to struggle towards one’s ideals.

This mature happiness depends on our ability to manage dialectical interactions and maintain a proper balance between self and others, and yin and yang tendencies, whatever the situation. This ability of flexibility can be strengthened through self-cultivation of the four dimensions of personhood and exercising the three ironclad logics (i.e., having the courage to do the right thing only when we are sure that the decision has passed three critical tests of purpose, wisdom, and conscience). According to this model, the sweet spot of optimal harmony between opposing forces is the outcome of mature happiness (安樂/安康)—an authentic, spiritual, and enduring happiness that can be sustained amid sufferings (Dambrun & Ricard, 2011; Delle Fave et al., 2016; Wong, 2017c).

Transpersonal Psychology

Transpersonal psychology may be defined as a “spiritual psychology.” It is also heavily influenced by Eastern psychology. The transpersonal is defined as “experiences in which the sense of identity or

Transpersonal psychology has a focus on the understanding of consciousness and spirituality relating to the human experience (Clements et al., 2016). From this perspective, mature happiness would be considered as having a relationship with an interconnected world as well as self-expansive states related to spirituality and other human experiences where a person can find meaning. Meaning-making includes self-transcendence, relational wholeness, and transformation. Other aspects of transpersonal psychology focus on the depth approach, where a person extends themselves outwardly through spirituality and morality to help other people. Finding meaning, from this view, emphasizes upward ego expansion such as transcendence and having spiritual experiences.

The transpersonal stance sees becoming whole or coming into “Being” as a transformation in the spiritual sense (Cortright, 1997). An individual’s movement into Being has been described by transcendence through nature, in the company of others, or by infusion of a higher power or Divine existence. This movement into Being can instill mature happiness by allowing for more inner peace, calmness, self-awareness, and

Through spiritual transformation, the conscious grows, becomes more defined, and accesses more wisdom, compassion, empathy, and sensitivity towards the self and others (Cortright, 1997). People enter this spiritual and transpersonal realm by three different spiritual means that occur: through the body, the mind, or into consciousness. According to Cortright (1997), the person who experiences this kind of transformation becomes more centered on their own spiritual consciousness. This way of being and spiritual consciousness is intrinsically more joyous and not dependent on extrinsic rewards for happiness.

Maslow (1964) advocated for love, creativity, self-growth, self-actualization, and higher values as the pre-condition for psychological health and mature happiness. All transpersonal psychology approaches focus on fostering higher human development and deal extensively with concerns related to human values and spiritual experiences (Kasprow & Scotton, 1999); these spiritual experiences are characterized by altruism, creativity, and feelings of human connectedness that are universal in life. Such human experiences have been reported across cultures and play a major role in understanding mature happiness. William James (1987) suggested that spiritual experiences should not be judged based on a particular cultural or religious orientation but should instead be judged based on their effect on people. Carl Jung was one of the first to include a spiritual approach in depth psychology. Jung (1967) introduced the concept that consciousness has within itself strong tendencies towards personal growth and evolution and that higher states of consciousness continue throughout our lives.

Transpersonal psychology identifies a construct of self-transcendence where the ego, the self, and its needs are transcended (Koltko-Rivera, 2006). When an individual self-actualizes at this level, the individual’s own needs are set aside in favor of serving others and, to some, a higher power. Recognizing the concepts of self-transcendence may lead to a deeper understanding of mature happiness. Some aspects of self-transcendence research that are important to recognize include a knowledge of worldviews regarding the meaning of life, understanding wisdom, and integrating religion and spirituality into conceptualizing the human condition. According to Maslow (1964), self-transcendence is a doorway to complete happiness. Wong (2016b) has recently expanded Maslow’s view by integrating it with Frankl’s concept of self-transcendence.

Contributions from Eastern Psychology

Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and transpersonal psychology all contribute to a deeper understanding of happiness that emphasizes attunement with self, others, and the world (Clements et al., 2016). The recognition of spirituality as an ally to personal development and mature happiness in these perspectives is vital to understanding the positive states of mind available to us when we are able to find deeper meaning and satisfaction. The conceptions of mature happiness according to transpersonal psychological theory and Eastern traditions are that finding meaning in life, contentment, inner peace, harmony, and connectedness to other people and a higher power bring about a positive state of mind and a spiritual attunement that is less dependent on circumstances. This spiritual perspective allows for the understanding of what mature happiness is and why this state of happiness can endure suffering, hardships, and problems.

Positive psychology, transpersonal psychology, and Eastern philosophy together allow for greater knowledge of the functioning of the mind and higher states of consciousness leading to mature happiness (Clements et al., 2016). These traditions illuminate a shift from unwholesome and unhealthy mental attitudes to wholesome and healthy mental properties. The transformative process is a journey in which the positive and negative aspects of living become an energy force that can be felt and channeled personally and universally. Gaining happiness in the world happens in the small and big moments of life. According to Clements et al. (2016), states of joy and happiness can be found through spiritual means in the forms of prayer, meditation, listening, learning about other people’s experiences and cultures, and meaning pursuits.

Mature happiness is a complete kind of happiness (Watts, 1940). This kind of happiness belongs to the individual and remains strong even in the face of suffering. Mature happiness persists through joy and sorrow. It is a spiritual undertone resulting from the positive and whole-hearted acceptance of the ups and downs of the tides in life. This kind of happiness comes when a person depends absolutely on their inner being and soul in connection

The motive of mature happiness is neither the activity itself, nor the positive emotion associated with it, but a sense of being characterized by serenity, harmony, attunement, being connected with the transcendental, and a deep appreciation of life itself.

Contextual Factors

The starting point in the

Various researchers have suggested the need to include contextual factors that may hinder

A comprehensive objective misery index should include current observable external conditions, such as pollution, poverty, inequality, toxic workplace, discrimination, oppression, violence incidents, accidents, natural disasters, disability, illness, lack of freedom of speech, lack of employment opportunities, and lack of community involvement (e.g., Graham, 2017; Helliwell, Huang & Wang, 2014; Ott, 2010; Putnam, 2000; Sen, 1992). The Happy Planet Index (HPI) (Jeffrey, Wheatley, & Abdallah, 2016) provides an alternative measure of wellbeing—it measures what matters for sustainable wellbeing for all by factoring in ecological footprint, which is important for achieving long, happy, and sustainable lives. According to this measure, poorer developing countries rank higher than rich developed countries. For example, in 2016, Costa Rica ranked highest in spite of its poverty because 99% of its electricity came from renewable sources. In other words, rich and developed nations with much larger ecological footprints rank lower in sustainable

A comprehensive subjective misery index should include loneliness, guilt, regret, fear of failure, fear of exposure of past transgressions,

In the context of high levels in both objective and subjective misery indexes, sufficient spiritual existential resources are a part of the inner resources in

Therefore, a comprehensive account of wellbeing needs to take into account (1) contextual factors, (2) inner resources, and (3) happiness measures. Any statement about wellbeing needs to be based on the complex interactions of these factors.

Methodologically, we can incorporate contextual factors in two ways. First, we can experimentally compare people who score high on the misery index (both subjective and objective) with people who score low on the misery index and different amounts of resources in different measures of happiness. We believe that CasMac predicts the presence of mature happiness under the high misery condition, because it not only reduces and transform

We can also study the effect of contextual factors statistically, either by covarying out the contextual factors or doing

In sum, the recognition of contextual factors, spiritual-existential resources, and mature happiness represents a new frontier of research on global

Concluding Discussion

There are semantic difficulties in defining happiness and wellbeing; however, most researchers consider these two words as the umbrella terms (Delle Fave, 2016). Hedonic happiness is related to subjective

In contrast, the motive of mature (noetic) happiness is neither positive emotion nor virtuous activity, but a positive mental state or sense of being that is characterized by inner harmony, tranquility, and

Mature happiness encompasses psychological

This chapter has provided evidence for both the need for mature happiness and its unique nature of being able to survive all the hardships and adversities life may throw at us. We have also provided the theoretical and methodological framework for research on mature happiness as the new frontier for global wellbeing research.

Traditional measures of wellbeing have neglected the concept of balance and harmony as emphasized by Eastern philosophies. What is missing in these models is the spiritual-existential dimension in dealing with internal turmoil. It is worth quoting that,

The attainment of a balanced life (Sirgy and Wu, 2009), in which negative aspects are counterbalanced by positive ones, appears a much more realistic aspiration than the pursuit of a steady condition of high satisfaction and positive affect, at both the individual and social levels (Wong, 2011). (Delle Fave, 2016, p. 85)

After a thorough critique of the current misguided happiness craze, John Schumaker (2007) provides the following ten happiness keys, which capture the spiritual and relational aspects of noetic happiness:

- Achieving something useful and challenging by doing what one does best;

- Living in harmonious relationship with others and being accepted as a significant group member;

- Enjoying intimate relationships with family and friends;

- Helping others and taking part in something that transcends self-interest;

- Accepting the limitations and realities imposed by life and nature;

- Embracing religion and spirituality as a significant aspect of life;

- Treating each other with fairness and justice;

- Enjoying the gifts of nature in everyday life;

- Learning new things so that we can grow continually; and

- Appreciating each moment of life.

Although meaning plays an important role in mature or noetic happiness, it is different from eudaimonic happiness because the emphasis is on the spiritual and existential capability in enduring adversities and maintaining a sense of inner peace at all times. Furthermore, these two types of happiness include different

To develop a comprehensive and valid measure of spiritually-oriented mature happiness, more research needs to be done on the seven key constituents of mature happiness and develop operational definitions:

- Inner serenity or tranquility;

- Being at peace with one’s conscience and thoughts;

- Being at peace with the world and a Higher Power;

- Staying composed in good or bad times, avoiding mood fluctuations;

- Being attuned to changing circumstances;

- Feeling connected with all people, including those who are difficult; and

- Maintaining a positive frame of mind, even in the darkest hour.

According to Alexandrova (2017), it is more helpful to develop good scientific measures of contextual wellbeing at the mid-level about happiness or mental health in specific circumstances. In this chapter, we focused on the noetic happiness of people who are in difficult circumstances or have a high misery index. This kind of research is more likely to yield results helpful to the suffering masses.

We began the chapter by describing the search for happiness in times of suffering. As long as the capacity for evil is a part of human nature, as long as self-centered ignorance and greed hold sway, there will always be human struggles and suffering. However, we believe that if we pursue mature happiness as a result of life education (Wong, 2017d) or spiritual awakening, and if we embrace the dark side of life and cultivate compassion, good will prevail over evil, and love will overcome hate. Therefore, we want to end this chapter with a speech given at the National Book Awards by this year’s lifetime achievement award winner Annie Proulx (National Book Foundation, 2017; see bit.ly/AnnieProulxNBF), a moving reminder to hope for happy endings, even though we live in Kafkaesque times.

References

- Alexandrova, A. (2017). A philosophy for the science of well-being. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Ani. (2016, February 15). Air pollution claims 5.5m lives annually. DNA India. Retrieved from http://www.dnaindia.com/scitech/report-air-pollution-claims-55m-lives-annually-2177930

- Batthyány, A., & Russo-Netzer, P. (Eds.). (2014). Meaning in positive and existential psychology. New York, NY: Springer.

- Batthyány, A., Russo-Netzer, P., & Schulenberg, S. (Eds.). (2016). Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy. New York, NY: Springer.

- Bixler, M., & Martinez, M. (2016, April 18). War forced half of all Syrians from home. Here’s where they went. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2015/09/11/world/syria-refugee-crisis-when-war-displaces-half-a-country/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, August 1). Prescription opioid overdose data. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html

- Chen, Y. H. (2006). Coping with suffering: The Buddhist perspective. In P. T. P. Wong & L. C. J. Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping. Langley, BC: Springer.

- Clements, C. J., Kaklauskas, F. J., Hocoy, D. & Hoffman, L. (2016). History, development, and contemporary perspectives of transpersonal psychology. In, C. J. Clements, F. J. Kaklauskas, D. Hocoy, & L. Hoffman (Eds.), Shadows and light: Theory, research

and practice in transpersonal psychology (Volume 1: Principles and practices) (Section 1). Colorado Springs, CO: University Professors Press. - Cortright, B. (1997). Psychotherapy and

spirit : Theory and practice in transpersonal psychotherapy. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. - Dalai Lama & Cutler, H. C. (1998). The art of happiness: A handbook for living. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

- Dambrun, M., & Ricard, M. (2011). Self-centeredness and selflessness: A theory of self-based psychological functioning and its consequences for happiness. Review of General Psychology, 15(2), 138-157. doi:10.1037/a0023059

- David, S. (2016). Emotional agility: Get unstuck, embrace change, and thrive in work and life. New York, NY: Avery.

- Delle Fave, A. (2016). Subjective indicators of well-being: Conceptual background and applications in social sciences. In L. Bruni & P L. Porta (Eds.), Handbook of research methods and applications in happiness and quality of life (pp. 71-89). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Wissing, M. P., Araujo, U., Solano, A. C., Freire, T., … & Nakamura, J. (2016). Lay definitions of happiness across nations: The primacy of inner harmony and relational connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(3), doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00030.

- Dhiman, S. (2008). Cultivating mindfulness: The Buddhist art of paying attention to attention. Interbeing, 2(2), 35-52.

- Disabato, D. J., Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L., & Jarden, A. (2016). Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychological assessment, 28(5), 471.

- Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-sided: How the relentless promotion of positive thinking has undermined America. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positive: Top-notch research reveals the 3-to-1 ratio that will change your life. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

- Gilbert, J. H. (1895). Dictionary of burning words of brilliant writers. New York, NY: Ketcham.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind: A new approach to life’s challenges. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

- Gilbert, P., & Choden. (2014). Mindful compassion: How the science of compassion can help you understand your emotions, live in the

present, and connect deeply with others. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger. - Graham, C. (2017). Happiness for all? Unequal hopes and lives in pursuit of the American dream. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hanke, S. (2017, February 9). Misery Index: The world’s saddest (and happiest) countries. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevehanke/2017/02/09/misery-index-ranking-the-worlds-saddest-and-happiest-countries/#6683ec204448

- Hanson, R. (2013). Hardwiring happiness: The new brain science of contentment, calm, and confidence. New York, NY: Harmony Books.

- Haybron, D. M. (2013). Happiness: A very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2014). Social capital and well-being in times of crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 145-162.

- Heppner, P. P., Heppner, M. J., Lee, D.-G., Wang, Y.-W., Park, H.-J., & Wang, L.-F. (2006). Development and validation of a collectivistic coping styles inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 107-125.

- Ho, D. Y. F. (1996). Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 155-165). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Ho, D. Y. F. (1998). Indigenous psychologies: Asian perspectives. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 88-103.

- Hwang, K. K. (2011). The Mandala model of self. Psychological Studies, 56, 329-334. doi:10.1007/s12646-011-0110-1

- Hwang, K. K. (2012). Foundations of Chinese psychology: Confucian social relations. New York, NY: Springer.

- Ingraham, C. (2017, December 6). Not only are Americans becoming less happy—we’re experiencing more pain too. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/12/06/not-only-are-americans-becoming-less-happy-were-experiencing-more-pain-too/?utm_term=.5c5e0692e809

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2016). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- James, W. (1987). Writings, 1902-1910 (No. 38, Library of America Series). New York, NY: Library of America.

- Jeffrey, J., Wheatley, H., & Abdallah, S. (2016). Happy Planet Index. New Economics Foundation. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5735c421e321402778ee0ce9/t/57e0052d440243730fdf03f3/1474299185121/Briefing+paper+-+HPI+2016.pdf/

- Johnson, S. (2017, November 13). More than 15,000 scientists issue a “warning to humanity.” Big Think. Retrieved from http://bigthink.com/stephen-johnson/15000-scientists-from-around-the-world-issue-warning-to-humanity

- Jung, C. G. (1967). The transformation of libido (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al. (Series Eds.), The collected works of C.G. Jung (vol. 5, 2nd ed., pp. 142-170). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kapala, M. (2015). Existential/spiritual resources and the subjective quality of life experiences among elderly adults. Polish Journal of Applied Psychology, 13(4), 123-168. doi:10.1515/pjap-2015-0046

- Kasprow, M. C., & Scotton, B. W. (1999). A review of transpersonal theory and its application to the practice of psychotherapy. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 8(1), 12-23.

- Keller, H. (1903). Optimism: An

essay . New York, NY: Crowell. - Koltko-Rivera, M. (2006). Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology, 10(4), 302-317. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.10.4.302

- Kornfield, J. (2008). The wise heart: A guide to the universal teachings of Buddhist psychology. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

- Kwee, M. G. T. (2012). Relational Buddhism: A psychological quest for meaning and sustainable happiness. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.; pp. 249-273). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lehrhaupt, L., & Meibert, P. (2017). Mindfulness-based stress reduction: The MBSR program for enhancing health and vitality. Novato, CA: New World Library.

- Linley, P. A., Joseph, S., Harrington, S., & Wood, A. M. (2007). Positive psychology: Past, present, and (possible) future. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 3-16. doi:10.1080/17439760500372796

- Maddi, S. R. (2004). Hardiness: An operationalization of existential courage. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44(3), 279-298. doi:10.1177/0022167804266101

- Maddi, S. R. (2013). Hardiness as the existential courage to grow through searching for meaning. In J. Hicks & C. Routledge (Eds.), The experience of meaning in life (pp. 227-239). Dordrecht, Switzerland: Springer.

- Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak-experiences. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

- May, R. (1975). The courage to create. New York, NY: Norton.

- McMahon, D. M. (2017, April 18). For most of history, people didn’t assume they deserved to be happy. What changed? Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/958677/happiness-a-history-author-darrin-m-mcmahon-explains-when-the-idea-of-happiness-was-invented/

- National Book Foundation. (2017).

Distinguished contribution to American letters, 2017. Retrieved from http://www.nationalbook.org/amerletters_2017_aproulx.html#.Wi7PgrQ-dTZ - Norberg, J. (2017). Progress: Ten reasons to look forward to the future. London, UK: Oneworld.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). Women and human development: The capabilities approach (Vol. 3). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2014). Residents of poor nations have a greater sense of meaning in life than residents of wealthy nations. Psychological Science, 25(2), 422-430.

- Ott, J. (2010). Greater happiness for a greater number: Some non-controversial options for government. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 631-647.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Pinto, M. (2014). Confucius on psychological peace and joy. San Francisco, CA: Blurb Creative.

- Powell, S. J. (1989). Happiness is an inside job. Allen, Texas: Tabor Publishing.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Rahula, W. (1974). What the Buddha taught: Revised and expanded edition with texts from Suttas and Dhammapada. New York, NY: Grove Press.

- Ricard, M. (2007). Happiness: A guide to developing life’s most important skill (Trans. J. Browner). New York, NY: Little, Brown, & Co.

- Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 139-170.

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069-1081.

- School of Positive Transformation. (2017).

Mindfulness based flourishing (positive mindfulness). Retrieved from https://courses.schoolofpositivetransformation.com/courses/positive-mindfulness-program - Schumaker, J. F. (2007). In search of happiness: Understanding an endangered state of mind. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011).

Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press. - Selvaraj, J. (2015). Human development and economics of happiness utility

enters through back door. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 5(11), 73-78. - Sen, A. (1992). Inequality

reexamined . Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. - Shamus, K. J. (2017, February 16). Poll: ‘Political climate’ is freaking most of us out. USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2017/02/16/poll-two-thirds-americans-stressed-future-us-politics/97986834/

- Shiah, Y.-J. (2016). From self to nonself: The nonself theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 124. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00124

- Shontell, A. (2016, January 27). A 69-year-old monk who scientists call the ‘world’s happiest man’ says the secret to being happy takes just 15 minutes a day. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-be-happier-according-to-matthieu-ricard-the-worlds-happiest-man-2016-1/

- Smith, E. E. (2017). The power of meaning: Crafting a life that matters. New York, NY: Crown.

- Stanton, E. A. (2007). The human development index: A history. Political Economy Research Institute, Working Paper Series, no. 127. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Sundararajan, L. (2014). The function of negative emotions in the Confucian tradition. In W. G. Parrott (Ed.), The positive side of negative emotions (pp. 179-197). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Tavernise, S. (2016, April 22). U.S. suicide rate surges to a 30-year high. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/22/health/us-suicide-rate-surges-to-a-30-year-high.html?_r=0

- Thin, N., Tarragona, M., Wong, P. T. P., Jarden, R., Bartholomaeus, J., & Jarden, A. (2017). Book review for International Journal of Wellbeing. Estes, Richard J., and M. Joseph Sirgy [eds] (2017) The Pursuit of Human Well-Being: The Untold Global History. Dordrecht: Springer. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7(1), 84-92. doi:10.5502/ijw.v7i1.636

- Thompson, N. A. (2017, July 16). The unwanted: Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2017/07/16/asia/bangladesh-

myanmar –rohingya -refugees/index.html - Thomson Reuters. (2017, March 30). ‘Let’s talk,’ WHO says, as depression rates rise 18% in a decade. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/health/depression-who-1.4047509

- Tran, N. (2014, November 29). Existential positive psychology: Big questions, big answers. Positive Psychology Program. Retrieved from https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/existential-positive-psychology/

- Veenhoven, R. (2014). World Database of Happiness.

Happiness of Nations. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Erasmus University. Retrieved from http://worlddarabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/ - Walsh, R. & Vaughan, F. (1993). On transpersonal definitions. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 25(2), 125-182.

- Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 271-360.

- Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Williams, M. K., Bede Agocha, V., … & Brent Donnellan, M. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41-61.

- Watts, A. W. (1940). The meaning of happiness: The quest for freedom of the spirit in modern psychology and the wisdom of the East. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Whippman, R. (2016). America the anxious: How our pursuit of happiness is creating a nation of nervous wrecks. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1993). Effective management of life stress: The resource-congruence model. Stress Medicine, 9(1), 51-60.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Spirituality, meaning, and successful aging. In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 359-394). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2001, October). Tragic optimism, realistic pessimism, and mature happiness. Paper presented at the Positive Psychology Summit, Washington, DC.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2008). To hell and back and what I have learned about happiness. International Network on Personal Meaning. Retrieved from http://www.meaning.ca/archives/archive/art_hell_and_back_P_Wong.html

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009a). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany, & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009b). Existential positive psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 361-368). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009c). Chinese positive psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 148-156). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012a). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). From logotherapy to meaning-centered counseling and therapy. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 619-647). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). From attunement to a

meaning-centred good life: Book review of Daniel Haybron’s Happiness: A very short introduction. International Journal of Wellbeing, 4(2), 100-105. doi:10.5502/ijw.v4i2.5 - Wong, P. T. P. (2014b). The positive psychology of grit: The defiant power of the human spirit [Review of the film Unbroken]. PsycCRITIQUES, 60(25). doi:10.1037/a0039390

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014c). Meaning in life. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 3894-3898). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015, December). The meaning hypothesis of living a good life: Virtue, happiness, and meaning. Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina. (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Chinese positive psychology revisited. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/174/157

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178/141

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016c, October 18). The good life through polarity and transcendence (Part 1 of 2). The Virtue Blog. Retrieved from https://thevirtueblog.com/2016/10/18/the-good-life-through-polarity-and-transcendence-part-1/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017a, October 5). Meaning and flourishing in suffering. Invited talk presented at Fo Guang University, Yilan, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017b). Meaning-centered approach to research and therapy, second wave positive psychology, and the future of humanistic psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/hum0000062

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017c, October 14). Chinese indigenous psychology and PP 2.0. Invited talk presented at the National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017d, October 3). Lessons of life intelligence through life education. Invited talk presented at Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017e). Coping and stress. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 886-890). New York, NY: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017f, September 29). The courage to live well and die well. Keynote presented at the 2017 Life Education International Academic Conference at the National Taipei University of Nursing and Health Science, Taipei, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017g, October 14). Adler versus Frankl: Similarities and differences. Invited talk presented at the Taiwan Society of Adlerian Psychology at the National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017h). Existential theoretical framework. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 1375-1378). New York, NY: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017i, May 16). Courage, faith, meaning, and mature happiness. Positive Living Newsletter. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/inpm-presidents-report-may-2017

- Wong, P. T. P., Carreno, D. F., & Gongora Oliver, B. (in press). Death acceptance and the meaning-centered approach to end-of-life care. In R. E. Menzies, R. G. Menzies, & L. Iverach (Eds.), Curing the dread of death: Theory, research, and practice. Brisbane, Queensland: Australian Academic Press.

- Wong, P. T. P., Ivtzan, I., & Lomas, T. (2017). Good work: A

meaning-centred approach. In L. G. Oades, M. F. Steger, A. Delle Fave, & J. Passmore (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of the psychology of positivity and strengths-based approaches at work (pp. 233-247). West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell. - Wong, P. T. P., & Fry, P. S. (Eds.). (1998). The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Page, D. (2003, October). Servant leadership: An Opponent-Process Model and the Revised Servant Leadership Profile. Address presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, School of Global Leadership & Entrepreneurship, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Reilly, T. (2017, August 15). Frankl’s self-transcendence model and virtue ethics (Part 1 of 2). The Virtue Blog. Retrieved from https://thevirtueblog.com/2017/08/15/frankls-self-transcendence-model-and-virtue-ethics-part-1-of-2/

- Wong, P. T. P., Reker, G. T. & Peacock, E. (2006). The resource-congruence model of coping and the development of the Coping Schema Inventory. In P. T. P. Wong, & L. C. J., Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 223-283). New York, NY: Springer.

- World Health Organization. (2001). Mental health: New understanding, new hope. The world health report 2001. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/

- Yan, A. (2017). Pollution claims 1.8 million lives in China, latest research says. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from http://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2116342/pollution-claims-18-million-lives-china-latest-research-says

- Yang, K. S. (1988). Chinese filial piety: A conceptual analysis. In K. S. Yang (Ed.), The Chinese mind (pp. 39-73). Taipei, Taiwan: Guigan Book. (In Chinese)

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.