MEETUP 2018

Decoding Peterson’s

12 Rules for Life

This is the first of four Meetups on “Decoding Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules of Life,” hosted by Dr. Paul Wong for the INPM’s Meaningful Living Project. For an overview of this Meetup series, see below.

“Life is suffering.

Love is the desire to see unnecessary suffering ameliorated.

Truth is the handmaiden of love.

Dialogue is the pathway to truth.

Humility is recognition of personal insufficiency and the willingness to learn.

To learn is to die voluntarily and be born again, in great ways and small.

So, speech must be untrammeled, so that dialogue can take place,

so that we can all humbly learn,

so that truth can serve love,

so that suffering can be ameliorated,

so that we can all stumble forward to the Kingdom of God.”— Jordan Peterson, Banned lecture at Linfield College: Ethics and Free Speech

Just imagine driving in a city without any traffic regulations or living in a country without state-enforced laws. Likewise, you cannot go through life without getting into trouble if you do not follow some rules of life; the alternative is nihilism, chaos, bondage to our desires, or slavery to totalitarianism. The question is: “What kind of rules do you choose to follow?”

Given our distaste for rules and the prevailing mentality of moral relativism, many people believe that social science or positive psychology can provide the answer we need on how to live a good life and flourish. Professor Jordan Peterson makes the case that science deals with objective facts and is inadequate in providing answers to the metaphysical questions of human existence and the moral compass and core values for individual lives. He prefers to have his rules be based on ancient wisdom, particularly the wisdom of the Bible.

What makes Peterson appealing to the Christian community is that he is able to rephrase their beliefs into metaphors and evolutionary biology, thus making them more respectable and acceptable to the larger academic community. “Existence at that cross is suffering and transformation—and that fact, above all, needed to be voluntarily accepted” (Peterson, 2018, xxxiii). The crucifixion of Christ simultaneously reveals sin-related suffering and God’s gracious love for our rebirth. Death and transformation are simultaneous connected. His insight about the significance of crucifixion is both Biblically correct and theologically profound.

You may not agree with him, but Peterson does have some provocative insights and helpful advice for individuals confused or defeated by life. He argues that, by their very nature, human beings need moral rules and a system of values in order to survive and thrive in a world full of evil and suffering; we ignore these rules at our own peril. “We require rules, standards, values—alone and together… We need to stay on the straight and narrow path” (Peterson, 2018, p. xxxiv). His 12 rules tell us how we can follow the narrow line between chaos and order, or yin and yang.

“It can be tough to parse the Peterson phenomenon. For one thing, it seems as if there are multiple Petersons, each appealing to, or in some cases alienating, separate audiences.” (Bartlett, 2018). For example, it can be very frustrating to understand Peterson if you do not have the necessary biblical background, because he likes to do biblical exegesis to support his thesis, and his book represents his attempt at a synthesis of psychology, biology, mythology, and religion, especially Christianity.

“It can be tough to parse the Peterson phenomenon. For one thing, it seems as if there are multiple Petersons, each appealing to, or in some cases alienating, separate audiences.” (Bartlett, 2018). For example, it can be very frustrating to understand Peterson if you do not have the necessary biblical background, because he likes to do biblical exegesis to support his thesis, and his book represents his attempt at a synthesis of psychology, biology, mythology, and religion, especially Christianity.

This book is a difficult and frustrating yet rewarding read. It is equally frustrating to go through his book if you are trained in linear writing with Earnest Hemingway’s economy of words, because Peterson’s narrative style is both recursive and verbose, more like the Ulysses by James Joyce. He prefers a roundabout and convoluted way of arriving at an answer and likes to use metaphors, analogies, and Christian code words. My quote of Peterson’s banned lecture at the beginning of this chapter illustrates his writing style. I hope that my effort in decoding the text of 12 Rules of Life makes this book more understandable to readers frustrated by the above barriers.

The Unique Contributions of this Book

In the first two chapters, Peterson lays down the two pillars of his beliefs: first, that science is a description of the laws of things in nature, and second, that religion is the narrative of the laws of moral action in human life. God or some sort of higher power is operating in both spheres of reality. We need both domains to provide an adequate account of human existence. Like many of the past luminaries in science (e.g., Francis Bacon, Isaac Newtown, Albert Einstein) and many scientists at present (Quester, 2018), Peterson believes in the existence of God as the grounds for moral laws, because science by virtue of its nature is not capable for providing a moral foundation or answering the ultimate question about God’s existence; in fact, even modern science itself faces a moral challenge (Levin, 2006). At a time when religions are being dismissed as irrational and irrelevant because of the dominance of scientism and materialism, Peterson sounds a much-needed warning of the dangers facing civilization when nihilism and totalitarianism replace religious beliefs and spiritual values.

The success of Peterson’s book can be considered a publishing miracle at a time when the positive psychology of happiness dominates the popular culture and publication business. Without making any reference to positive psychology or Martin Seligman, Peterson has succeeded in effectively advocating an alternative vision of the good life that is much more robust, substantial, and realistic and succeeds in attracting millions of readers, in spite of the fact that it is a difficult book to read. I am so glad that he has accomplished with one book what I have not been achieved with two decades of research and publications.

I believe that Viktor Frankl’s (1985) Man’s Search for Meaning, Rick Warren’s (2012) The Purpose Driven Life, and Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life have one thing in common for their extraordinary appeal: they all proceed from a spiritual worldview that recognizes the existence of God and a transcendental reality. From this perspective, they emphasize that the good life is not about what you can get from life, but what life demands from you—your responsibility to make a special contribution for the glory of God and for the wellbeing of humanity.

I believe that Viktor Frankl’s (1985) Man’s Search for Meaning, Rick Warren’s (2012) The Purpose Driven Life, and Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life have one thing in common for their extraordinary appeal: they all proceed from a spiritual worldview that recognizes the existence of God and a transcendental reality. From this perspective, they emphasize that the good life is not about what you can get from life, but what life demands from you—your responsibility to make a special contribution for the glory of God and for the wellbeing of humanity.

Another commonality among these three bestsellers is that they all begin with a realistic assessment of a world that is broken and in need of redemption. Everyone I know, including myself, struggles with their personal demons and the problems of living in a scary, cruel, and unfair world. The only people who deny these problems are those die-hard positive psychology believers. By their denial, they have brought not only unnecessary discredit to positive psychology, but also unintentional harm by minimizing the suffering of people wounded by life.

The paradoxical self-transcendental view of personal growth (Wong, 2016c) shows up the shallowness of a positive psychology that focuses on personal happiness and success with meaning and character strengths serving only as tools for self-aggrandizement. Peterson is able to provide a vision of existential positive psychology where meaning, tragic optimism, and mature happiness come from overcoming the dark side of human existence.

Jordan Peterson has become the most successful and influential spokesperson for the humanistic-existential-transpersonal school of psychology since Carl Roger, Rollo May, and Abraham Maslow; unfortunately, they do not embrace him as their own because of his political views against transgender pronouns and postmodern Marxism. Personally, I feel that one should not let his political views obscure the importance of his contribution to the psychology of the good life.

The Importance of Moral Rules

Peterson’s rules are based on ancient wisdom (especially the Bible). By their very nature, human beings need to be guided by moral rules and values in order to survive and thrive in a world full of temptations and evils; we ignore these rules only at our own peril. “We require rules, standards, values—alone and together… We need to stay on the straight and narrow path” (Peterson, xxxiv). He challenges us to follow the narrow line between chaos and order or between yin and yang; it requires us to restore our beliefs in God as the source and foundation of our morality and stay away from nihilism and all kinds of totalitarian ideologies such as Marxism, postmodernism, rationalism, and scientism.

“Look, why don’t you make yourself into an individual and get the hell away from the ideology? … A lot of these kids are lost in the underworld, let’s say, in nihilism, and they turn to these ideological solutions because they don’t know what else to do. And they’re angry. It’s like, I have something better for them to do. Grow the hell up. And sort yourself out as an individual.” — Jordan Peterson

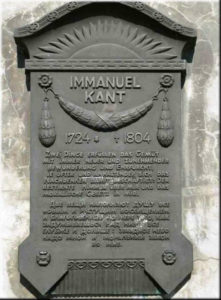

Philosophically, Peterson can identify with elements of theistic existentialism (Soren Kierkegaard) and deontological moral philosophy (Immanuel Kant). Kierkegaard (1941) stated that since God cannot be objectively studied, he needed to believe: “If I am capable of grasping God objectively, I do not believe, but precisely because I cannot do this I must believe” (p. 182). This is similar to a Biblical view of faith: “Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see” (Heb. 11:1). In order to live a hopeful life in a chaotic and uncertain world, we need a leap of faith.

Jordan Peterson’s rules are similar to Kant’s categorical imperative. According to Kant’s deontological moral theory, a person should treat other people as having inherent value, and not merely as a means to achieve one’s end, and a person should act that the principle of one’s act could become a universal law of human action in a world in which one would hope to live. Such a general moral law is a categorical imperative. Kant’s tombstone bears his last words: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: The starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.” Thus, the spiritual law of innate conscience that governs our behaviour is just as real and essential as the natural law that governs the movement of the stars.

Jordan Peterson’s rules are similar to Kant’s categorical imperative. According to Kant’s deontological moral theory, a person should treat other people as having inherent value, and not merely as a means to achieve one’s end, and a person should act that the principle of one’s act could become a universal law of human action in a world in which one would hope to live. Such a general moral law is a categorical imperative. Kant’s tombstone bears his last words: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: The starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.” Thus, the spiritual law of innate conscience that governs our behaviour is just as real and essential as the natural law that governs the movement of the stars.

Similarly, Peterson emphasizes that order demands rules or laws; chaos results in the absence of these rules. Therefore, to believe in God and to obey the moral law within us are the two essential rules for living the good life. Chaos often happens when we choose to disobey God’s moral rules, ignore cultural norms, and justify our bad behaviours (e.g., everybody is doing it; life is so hard, and I deserve some happiness; it won’t hurt if I just try it). Chaos also occurs when we ignore the fact that nature exists independent of our constructions; we simply cannot impose our own ideology on nature’s way of unequal distributions and dominance hierarchy. Trying to change natural categories, such as males and females or parents and children can be very unsettling to parents and society.

That is why we need to learn how to listen to God, who will reveal the mystery of the cosmos and His existence to those who seek with an open mind. We need to aim higher for a better future; we need to pursue God, who is the embodiment of the classical ideals of truth, goodness, and beauty. Such high aspirations are necessary for developing good character. Then, we need to exercise the responsibility of self-cultivation in order to achieve an ideal future through faith and a planned sequence of actions.

Rule 1: Stand up straight with your shoulders back

First and foremost, you must take responsibility for your own life and wellbeing in spite of a bleak reality. This rule sounds intuitive and is the moral imperative for a meaningful life according to Frankl (1985) and Wong (2012a). Peterson makes a compelling case that suffering is not only inevitable, but also reducible through assuming personal responsibility—to stand up straight and hold your head up to face the horrors of this world with courage, faith, the main theme of our 10th Biennial International Meaning Conference.

First and foremost, you must take responsibility for your own life and wellbeing in spite of a bleak reality. This rule sounds intuitive and is the moral imperative for a meaningful life according to Frankl (1985) and Wong (2012a). Peterson makes a compelling case that suffering is not only inevitable, but also reducible through assuming personal responsibility—to stand up straight and hold your head up to face the horrors of this world with courage, faith, the main theme of our 10th Biennial International Meaning Conference.

You need to adopt this positive posture towards life, because nature is cruel and unfair, and the dominance hierarchy will always be there. Your defiant attitude towards fate enables you to “accept the terrible responsibility of life, with eyes wide open. It means deciding to voluntarily transform the chaos of potential into the reality of habitable order. It means adopting the burden of self-conscious vulnerability… It means willingly undertaking the sacrifices necessary to generate a productive and meaningful reality (it means acting to please God, in the ancient language)” (Peterson, 2018, p. 27).

In short, Peterson is challenging you to stop hunching around and whining about your misfortunes. Instead, make a conscious decision to improve yourself by bringing order to your life, cultivating your character and learning new skills, and carrying the burden of being a human being, because life is suffering. Changing your posture is the first step towards changing your attitude towards life. This is what I used to teach my Meetup group. There is actually scientific evidence supporting the importance of positive posture on motivation and happiness (Riskind & Gotay, 1982).

Peterson is actually a good psychologist. What he says about the meaning of life is exactly what I have been saying in second wave positive psychology (PP 2.0) since Seligman’s APA Presidential address. Positive psychology as usual (PP 1.0) posits that life is good, and you can enjoy life as a joy ride (e.g., Rubin, 2009). If that is your assumption, you won’t survive the horrors of life.

On the other hand, existential positive psychology (Wong, 1999) or PP 2.0 (Wong, 2012) posits that life is suffering. It’s hard to be a teenager, it’s hard to find a good job, it’s hard to have a good marriage, it’s hard to be a good parent, it’s hard to grow old and die. It’s hard to be a human being—period. If life treats you badly, that is tough, but that is also reality. Therefore, you need to arm yourself with a tough mental attitude to endure suffering and fight like a good soldier. That is the only way to survive and thrive in this competitive and harsh world. This happens to be consistent with Biblical teaching: “You therefore, my son, be strong in the grace that is in Christ Jesus. Suffer hardship with me, as a good soldier of Christ Jesus” (2 Tim. 2:1, 3).

There is plenty of scientific support for Peterson’s emphasis on the imperative of personal responsibility in a world full of competition, dominancy hierarchy, and unequal distribution. It is supported by research in sociobiology (Gilbert, 1989/2016; Wilson, 2000). It is also supported by extensive psychological research on self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2002), self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982), self-regulation (Bandura, 1999), self-control (Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007), and internal locus of control (Rotter, 1966). In sum, without assuming personal responsibility, no one can survive and thrive as a healthy adult.

Rule 2: Treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping

The logical next step is that your first moral responsibility is to take good care of yourself. You must treat yourself with same care and compassion as you treat your pets. If you are not able to love and take good care of your own wellbeing, how are you going to care for your neighbours or contribute to the wellbeing of society? Self-care should be the standard by which we care for others, according Gal. 5:14)

Peterson begins with the observation that many people take more care of their pets than their own lives. People engage in unhealthy lifestyles and self-sabotaging. Some people even self-destruct because of drug overdose, alcoholism, violence, and suicide. Why are they in such a mess? Why don’t they assume the responsibility of taking proper care of themselves? Peterson suggests that the above may represent cases of “silent suicide” when people have lost interest in life because of painful and hopeless existence. Some live in private hell because they have lost their moral compass, ideals, and reasons for living.

Peterson begins with the observation that many people take more care of their pets than their own lives. People engage in unhealthy lifestyles and self-sabotaging. Some people even self-destruct because of drug overdose, alcoholism, violence, and suicide. Why are they in such a mess? Why don’t they assume the responsibility of taking proper care of themselves? Peterson suggests that the above may represent cases of “silent suicide” when people have lost interest in life because of painful and hopeless existence. Some live in private hell because they have lost their moral compass, ideals, and reasons for living.

However, it takes a long, serpentine way to arrive at an answer. Peterson first stakes out his position that science cannot provide an answer, and we need to return to the oldest story, the Bible, to understand the predicament of human existence and the subjective experience of suffering.

Peterson’s logic is that human beings are finite; they can enjoy life as long as they follow the moral rule laid down by God, to not eat the forbidden fruit. This basic law means that, as long as we recognize our limitations and honour the moral law (which is the first of the Ten Commandments), we will enjoy fellowship with God and live happily in a world of order. But when we listen to the Serpent and want to become as wise as God, order is replaced by chaos and we degenerate into hell. This hell involves the beginning of consciousness of our shame, guilt, and mortality. Such painful awareness may drive people into self-destructive behaviours.

Thus, Peterson traces the origin of human suffering to the fall of Adam and Eve. They could enjoy life as long as they followed moral rule laid down by God not to eat forbidden fruit “The worst of all possible snakes is the eternal human proclivity for evil. The worst of all possible snakes is psychological, spiritual, personal, internal” (Peterson, 2018, p. 47).

We still suffer from consequences. When we think that we know as much as God, and we think all the answers to human problems are through scientific research or authoritarian ideology, we actually become sources of evil in the world and contribute to chaos. By trying to be like God and rejecting his moral imperative, and degenerate to the dark abyss of evil, suffering, despair, and chaos.

“Evil is the force that believes its knowledge is complete.” — Jordan Peterson

In Peterson’s words, “Chaos is the despair and horror you feel when you have been profoundly betrayed. It is the place you end up when things fall apart, when your dreams die, your career collapses, or your marriage ends… Order is the place and time where the oft-invisible axioms you live by organize your experience and your actions so that what should happen does happen” (Peterson, 2018, pp. 35, 37). However, “in its positive guise, chaos is possibility itself, the source of ideas, the mysterious realm of generation and birth. As a negative force, it is the impenetrable darkness of cave and the accident by the side of the road” (p. 42). Thus, even in times of chaos, there is the opportunity of rebirth, transformation, and return to order; this will happen when we choose to accept our need for some time-tested ancient wisdom and traditional moral rules. This is the Taoist principle of yin yang.

Thus, meaning in life does not come from the straightforward pursuit of one’s ideal career and relationships as advocated by so many positive psychologists. Rather, meaning comes from wisely navigating between security and risks, success and failure, or familiar grounds of established knowledge and unproven new possibilities, as proposed by Wong’s (2012b) dual-system model of achieving meaning and wellbeing.

I totally agree with Peterson, when he writes, “We eternally inhabit order, surrounded by chaos. We eternally occupy known territory, surrounded by the unknowns. We experience meaningful engagement when we mediate appropriately between them… Chaos and order make up the eternal, transcendent environment of the living” (Peterson, 2018, p. 43). This is the world of transcendence and polarity, as described by Wong (2016a).

We mess up our lives when we yield to nihilism and chaos. We experience meaning and mature happiness “from our deepest being” (Peterson, 2018, p. 44), when we return to God’s moral rules and take personal responsibility for our wellbeing in spite of the surrounding chaos.

Therefore, there is hope. No matter how broken your life is, there is still redeeming value because (a) you were made in God’s image, (b) you are unique, (c) you are important to others, and (d) you have something unique to contribute to the world. Therefore, you have to make a decision, whether you want to stay at the bottom of the abyss of despair, self-loathing, and self-destruction, or make your life better by assuming the responsibility to restore your self-respect, take care of yourself, and get professional help if necessary. This is also the message of Chapter 2 of Peterson’s book. This is also the message of meaning therapy (Wong, 2016b).

The following represents steps towards restoration. You can atone for your sins and walk with God again (without the grace of Christ) by:

- Know yourself — Know “where you are, so you can start to chart your course” (p. 65)

- Deserve respect — “You have a vital role to play in the unfolding destiny of the world” (p. 62)

- Restore order to your life — “Bring the divine force of Hope to bear on the world” (p. 63)

- Discipline yourself — Have the willpower to refine your personality, redirect your destination, and endure hardship. “He who has a why can bear almost any how”

- Aim at a more spiritual future — “You could help direct the world, on its careening trajectory, a bit more toward Heaven and a bit more away from Hell” (p. 63)

- Devote your life to something higher and bigger than yourself — “That would give you a Meaning, with a capital M. That would justify your miserable existence” (pp. 63-64)

- Navigate between Chaos and Order — You can recreate order in the midst of chaos, experience happiness in the midst of miseries.

Scientific Support

The message of restoration through pursuit of meaning and spirituality has much empirical research:

- Wong, P. T. P., Wong, L. C. J., McDonald, M. J., & Klaassen, D. W. (Eds.). (2012). The positive psychology of meaning and spirituality: Selected papers from Meaning Conferences. Birmingham, AL: Purpose Research.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Fry, P. S. (Eds.). (1998). The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Next Meetup: June 17, 2018

Decoding Peterson’s

12 Rules for life

References

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122-147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248-287.

- Bartlett, T. (2018, January 17). What’s so dangerous about Jordan Peterson? The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/What-s-So-Dangerous-About/242256

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351-355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Gilbert, P. (2016). Human nature and suffering. New York, NY: Routledge. (Original published in 1989)

- Kierkegaard, S. (1941). Concluding unscientific postscript (D. F. Swenson, Trans). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Levin, Y. (2006). The moral challenge of modern science. The New Atlantis: A Journal of Technology & Society, 14, 32-46. Retrieved from https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-moral-challenge-of-modern-science

- Peterson, J. B. (2018). 12 rules for life: An antidote to chaos. Toronto, ON: Random House.

- Quester, J. P. (2018, March 5). What did Newton, Darwin, and Einstein think about God’s existence? Owlcation. Retrieved from https://owlcation.com/humanities/Newton_Darwin_and_Einstein_on_God

- Riskind, J. H., & Gotay, C. C. (1982). Physical posture: Could it have regulatory or feedback effects on motivation and emotion? Motivation and Emotion, 6(3), 273-298. doi:10.1007/BF00992249

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General & Applied, 80(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

- Rubin, G. (2009). The happiness project: Or, why I spent a year trying to sing in the morning, clean my closets, fight right, read Aristotle, and generally have more fun. New York, NY: Harper.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Warren, R. (2012). The purpose-driven life: What on earth am I here for? Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Wilson, E. O. (2000). Sociobiology: The new synthesis (25th anniv. ed.). New York, NY: Harvard University Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012a). From logotherapy to meaning-centered counseling and therapy. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 619-647). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a, October 18). The good life through polarity and transcendence (Part 1 of 2). The Virtue Blog. Retrieved from https://thevirtueblog.com/2016/10/18/the-good-life-through-polarity-and-transcendence-part-1/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016c). Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178/141

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2018, April 22). You can’t go through life without a set of rules (Lesson 1). INPM. Retrieved from http://www.inpm.org/course-materials/course-materials-2018/

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.