Dr. Paul T. P. Wong’s autobiography, A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith, is published in weekly installments. Stay updated here.

The Many Faces of Poverty

One does not really understand poverty unless one has lived through it; it is a world which has its own rules and logic. I am grateful for the privilege of having experienced poverty—and survived. Both the darkest and the noblest aspects of human nature manifest themselves in dire poverty. For some, poverty justifies their worst brutality to exact revenge against an unfair world; for others, it inspires their bold idealism to treat all people as members of the human family.

This is a strange chapter of my life—thrown from a life of privilege to one of dire poverty. There was a surreal dreamlike quality to my life during that period; I managed to exist in two dimensions simultaneously and did not really know where I was at any time, but I knew that these two opposing forces shaped me to be the person I have become.

Living in a World of Two Realities

On one hand, there was the reality of the bitter struggle to stay alive—to find ways of making money and fending off the creditors for a few more days. It was a dark world in which the walls around you were closing in each day, threatening to crush or suffocate you unless you found some money. It was a dog-eat-dog world of loan sharks, gangsters, and prostitutes, a cesspool of degradation, corruption, and miseries.

Money was the only language that everyone understood and respected. Human decency, morality, and loyalty meant nothing. You survived on your wits and your guts. You had to get used to being treated as a piece of garbage. The real world was only for the rich, and it didn’t matter how they got their money. The problem with me was that poverty did not inspire me to strive to become rich. Somehow, I had experienced the precariousness of riches and seen firsthand the shallow and meaningless existence of rich people.

On the other hand, there was the idealism of striving to pursue the ideals of truth, beauty, and goodness. It was the struggle to hide myself in a sanctuary, unperturbed by the real word, where I could play my favourite violin pieces, such as Jules Massenet’s Meditation, Franz Schubert’s Serenade or Ave Maria. It was also a secret place where I could listen to the cassette tapes of my favourite music, such as Chopin’s Nocturnes, Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, and Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 16 in C major; these tapes were provided by my artistic classmate, whom I had defended against bullies (see Chapter 15). He also gave me free tickets to watch the Magic Bow three times because I so loved the violin song Romance by N. Paganini.

Classical music had the magical power of transporting me instantly from the abyss of suffering to a heavenly realm, where I experienced the trance-like state of being cleansed of all the pollutions and worries of the world and filled with ecstasy, as if I was climbing to the top of the staircase to heaven. How grateful I was to those great musicians that they had captured the language of heaven and translated it into musical notes for us mortals to enjoy for generations. In those moments of rapture, I discovered meaning and happiness despite the horrible circumstances I was in. Years later, I learned that this was what Viktor Frankl (1985) called the experiential value.

The Power of Great Literature

Just as classical musical expanded my soul and opened my eyes to pure beauty, great literature expanded my mind and opened my eyes to truth and goodness that enlightened. The pure arts sustained my ideal world in spite of the crushing burden of reality.

Just as classical musical expanded my soul and opened my eyes to pure beauty, great literature expanded my mind and opened my eyes to truth and goodness that enlightened. The pure arts sustained my ideal world in spite of the crushing burden of reality.

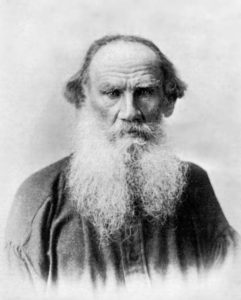

Apart from reading Chinese and British poems and Alexander Pushkin’s love poems, I devoted most of my time reading the great novels of Russian writers. The main reason why I was attracted to Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky was that they not only painted the human story on such a gigantic, all-encompassing canvas, they were also able to both plummet the dark depths of human existence and reveal the mysteries of human spiritual yearnings and divine love.

I devoured Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Anna Karenina, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, and A Confession with great hunger. I was deeply moved by A Confession. Although his conversion was a gradual process, when it was completed, his moral and spiritual transformation was evidenced in every aspect of his life, from giving up his possessions to pursuing the Gospel truth of loving God and one’s neighbours. His theology could be summed up in one word—love—as illustrated by a familiar quote from War and Peace:

Love hinders death. Love is life. All, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists, only because I love. Everything is united by it alone. Love is God, and to die means that I, a particle of love, shall return to the general and eternal source. (Tolstoy, 1869/1998, p. 1051).

Ultimately, all human problems can be solved by loving God and loving one’s neighbour. This made perfect sense to me as a young idealist. If this fundamental principle of love for all humans was not implemented, the world would continue to be torn apart by injustices and wars.

Ultimately, all human problems can be solved by loving God and loving one’s neighbour. This made perfect sense to me as a young idealist. If this fundamental principle of love for all humans was not implemented, the world would continue to be torn apart by injustices and wars.

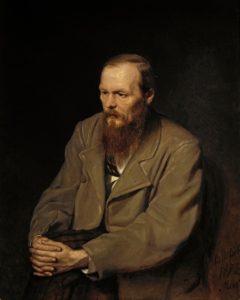

Similarly, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment had a strong impact on me. I was really encouraged to learn that a meaningful life was not dependent on possessions but on being engaged in meaningful relationships and meaningful work. The following Dostoevsky quote predated Frankl’s logotherapy, recognizing that people can suffer from mental illness if they neither have any reason for their survival nor any goal worthwhile to pursue.

The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for. (Dostoevsky, 1880/2003, p. 339).

The Power of Creative Writing

The third pillar that sustained me was creative writing. My lack of writing talents did not prevent me from writing my way out of darkness into light. At that time, I had no idea about the adaptive benefits of expressive writing; nor did I know about Viktor Frankl’s (1985) creative value as a pathway to meaning. To me, writing was just as natural as composing for a musician or painting for an artist.

However, I was not so much motivated to express my creative ideas as to relieve my inner pain. I wrote incessantly simply because I had to unload what weighed heavy on my heart. It could be a poem, or a reflective thought on life, or an aphorism inspired by my readings. The very act of writing granted me at least momentary solace.

This was the beginning of a lifelong habit of writing, especially writing daily inspirational statements designed to lift my own spirit and drive away the black dog of depression. Since then, I have in fact filled up hundreds of notebooks with such writings. Now, many of my inspirational statements have found their way online, such as on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and WordPress.

The Power of Learning

It was drilled in our heads since childhood that if we did not study hard, we would regret in our old age. The value of education was never questioned in our family, and learning to the best of our abilities was simply accepted as a fundamental human responsibility.

For me, another motivation to work was the desire to improve myself. For example, when I entered Grade 3 or 4, I was so concerned whether my intellectual capacity had grown that I often got out of my bed and quietly snuck into the dining room to test myself with the new textbooks.

After graduating from high school, I was worried that I would fall further and further behind if I did not study on my own, since most of my classmates had gone abroad for further studies. Such self- and peer-reference provided a strong motivation to improve myself continuously.

However, the biggest motivation came from the joy of learning. Since I did not have a definite career plan right after high school, I just wanted to study what interested me. I was able to borrow books on Chinese history, philosophy, and literature from Cao Ju-Ren (曹聚仁) and discussed with him any questions I might have (see Chapter 8 about my relationship with Mr. Cao).

In the 50s, the USA Information Center in Hong Kong provided a good library for a general liberal education. I was able to borrow English books on a variety of topics, from literature to philosophy. There was indeed an inexplicable joy in learning a new concept or developing a critical analysis of another issue. Such intrinsic motivation for learning has endured even into my old age.

Together, the above four pillars sustained my sanity through my darkest hours and gave meaning and substance to my difficult life. They expanded my horizon and enriched my mind; they provided a solid foundation for my future life.

The Downward Spiral of Poverty

Throughout those difficult days, each passing week became more desperate than the last, and there was no relief in sight. I could literally see our resources dwindle day by day, because there were only daily expenses, but no steady income.

You know you are poor when your parents’ fair-weather friends begin to avoid you. You used to call them Uncle or Auntie when they came to your house for dinner or to play Mah-jong. But now, they pretend that they do not know you, even to the point of walking on the other side of the street when they see you coming.

You know that you are poor, when you have to use cheap, coarse toilet paper, finally resorting to discarded old newspaper to clean yourself. I can assure you that it was neither comfortable nor hygienic, but what else can one do when one has no money to take care of this daily necessity?

You know that you are poor when your daily major worry is how to bring food to the table. One of my mother’s recipes was to break up a piece of dough into small pieces, cooking them in a bowl of hot water with a bit of oil and soy sauce. Another common dish in those days was boiled turnip or cabbage soup with a little soy sauce. Such meals did not have much nutritional value, but at least they temporarily removed our hunger pangs.

You know that you are poor when you have to pawn your possessions, beginning with the valuable items, such as jewelry, watches, and clothing.

Pawnshops can be easily recognized by their universal symbol, consisting of a bat holding a coin, signifying “fortune.” Pawnshops can be seen in every district; they represent poor people’s banks.

The universal sign in Hong Kong for pawn shops.

I visited many pawnshops in Kowloon and knew which ones offered a fair price for your belongings. The common rule of pawning is that if we did not redeem our belongings within a specified time with capital plus interest, the pawnshop was free to sell our belongings in second-hand markets.

Another universal feature of pawnshops is that once you got inside, you would face a high counter. You had to raise your item for pawning above your head in order for the pawnbroker or his assistant to receive it and assess its value.

The most humiliating situation was to take a suitcase of woolen sweaters and winter coats just to get 50HKD (or 10CAD). I acquired the habit of looking around to make sure that no one was watching me before I slipped in and out of the pawnshop. Well, someone had to do this unpleasant task to bring food to the table. Since I was the oldest son still at home, going to pawnshops became my job.

Finally, you know you are poor when you have to borrow from the poor. In those days, it was common for poor people to form a mutual help society, known as a wui (會). Based on my limited understanding, this was the poor people’s way of getting financial help. The members of a wui would meet several times a year and subscribe a share of certain dollar values; this is called gung wui (供會). Then, those who were in need of money would bid to collect the sum from all its members, which is called biu wui (標會). The one who had the greatest need for money would bid with the highest interest in order to collect the sum. This person then became a debtor to the society or wui, and had to repay his loan plus interest. The problem occurred when you were not able to meet your financial obligations after collecting the money from all the poor people in the wui. It broke my heart to hear so many poor people knocking on our door demanding repayments after we failed to pay back towards our loan for several months.

Although we were not poor to the point of becoming homeless, we had to rent out the entire front part of our condo; as a result, the whole family was squeezed into two little rooms at the back. Eventually, we had to move to a much smaller flat in a poor district.

The Adaptive Benefits of Poverty

It is no fun to be poor, but it can be good for your soul.

As I have mentioned earlier, the harsh reality of poverty made my ideal world of beauty, truth, and goodness all the more precious and real. I discovered this spiritual principle through my personal experience, that my need for meaning was much greater when my existence was full of pain. These two opposing realities complement each other in a strange, dialectical way.

The second unexpected benefit was health. In order to save the bus fee, I began to go to Pui Ching on foot, which was about two miles away from my Chatham Road home. At first, I alternated walking with running. Later, I built enough stamina to run all the way to school. Years later, my family physician in Peterborough commented that I had the heart of an athlete. I knew that this had to be the result of my daily running.

The third benefit was training in frustration toleration or the ability to endure failures and setbacks. When one is desperate for a job, one will be willing to try anything, even attempting to work that you are not prepared for. I did not mind being fired as an illustrator for a children’s magazine only after one week because I just did not have the talent or training. I did not mind being fired as a teacher at Mary Knoll Girls’ school only after one month, because I did not have the training and did not know how to maintain classroom discipline. I also accepted repeated rejections when I tried to make money as a freelancer, because I did not have Benedict’s talent, who was able to support himself through freelance writing right after high school (see Chapter 7).

However, it was hurtful when I was fired for no legitimate reason. For example, I got a job tutoring a 10-year-old boy in a very wealthy family. He was the only boy; he looked very pale and anxious. I was hired to supervise his homework. I never met his father, and his mother occasionally came home after shopping. The boy was dying for emotional security and relationship. He became attached to me very quickly to the point that he did not want me to go home. I was successful in getting him motivated to do his homework and improved his grades.

After he had learnt to do his homework without coaxing and close supervision, I was able to do some of my own reading while keeping an eye on his progress. His mother happened to come home one day and found me reading. The next day, I was fired. The boy was crying and pleading with his mother, who remained cold and unmoved. Even today, I could not understand why she would harm her own child for something so trivial. Actually, all she could have done was to tell me not to bring any of my own books to work.

I came to realize that the world was very unfair and one could get fired any time, even for doing good work. I received a heavy dosage of frustration training during my youth, and it prepared me well for the many trials and tribulations awaiting me in Canada. From the depth of my despair and frustration, I discovered the three essential ingredients of true grit: the capacity for tolerating frustration and hardships, the courage to face dangers and failures, and the ability to persist, come hell or high water. I discovered the important truth that failing, especially during the early years, is good for you. It is no accident that many years later, I chose frustration as my main area of research and have published extensively on the topic (e.g., Wong, 1979, 1995).

How to Solve the Problem of Poverty

During those difficult days, it was only natural for me to wrestle with the societal problem of poverty. Why should there be such a huge income gap between the haves and have-nots? What should the government do to address this problem of inequality and injustice?

I saw the ugly face of capitalism up front and personal; I saw their greed, selfishness, and moral corruption. I knew very well the evils of unbridled capitalism. In my idealist mind, the communist slogan of “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” seemed to describe a fairer economic system.

However, as I explored socialism and communism deeper, I was increasingly convinced that Karl Marx’s utopia of a classless society could not be implemented because of human greed and the corrupting power of a new communist ruling class. Stalin’s and Mao Zedong’s terror tactics to ensure their grip on power told me that the Marx-Lenin-Mao Zedong thought was nothing but a smoke screen to cover up a self-serving brutal dictatorship. On a personal level, I also experienced vicariously through family, friends and the countless Chinese refugees in Hong Kong the horrors of Mao’s reign.

Thus, I concluded that a socialist state that had the absolute power to control all the resources and redistribute wealth also had the power to take away people’s freedoms, rights, and even their lives. I was also convinced that it was impossible for any government to force all people into the same tight ideological box; such a totalitarian state was doomed to fail because history has shown that no tyrant has ever succeeded in turning all its citizens into satisfied “caged animals” content to live without freedom and self-determination.

As I have described earlier, during my teen years, I was poor but free to explore my interests and pursue my dreams. Even in my poorest moments, I would never have traded my freedom for “an iron bowl of rice,” because such an existence would be devoid of meaning and human dignity, and at the end I would lose both liberty and security, according to Benjamin Franklin.

Recently, after reading Madeline Thien’s novel Do Not Say We Have Nothing, I am even more convinced now than 60 years ago that any country willing to sacrifice millions of its innocent citizens in order to stay in power will not last long, even it was able to lift many people from poverty. That is because by nature “man shall not live by bread alone” (Matt. 4:4).

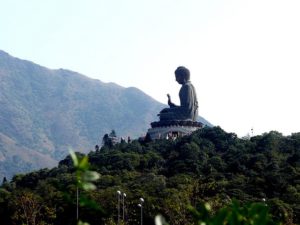

After many years of intellectual struggle, I am no closer to finding a solution to the problem of poverty. In the 50s, I was disappointed in both capitalism and socialism; therefore, I briefly entertained the idea of escaping from mainstream society to Lantau Island to live as a hermit. It did not take long before I realized that escapism would not solve the poverty problem, and that both capitalism and communism would one day descend on this pristine fishing village.

The Buddha on Lantau Island.

At present, my thinking is leaning toward “conscious capitalism” and meaning-centered good work (Wong, Ivtzan, & Lomas, 2016). Our best chance of creating a kinder and gentler society is through humanistic positive education which emphasizes meaning, compassion, and ethical responsibility. I can envisage an enlightened and voluntary classless society through such education efforts.

When we cultivate people’s personal responsibility, virtue ethics, and civic duty, they will be able to practice the paradoxical truth of becoming their best through self-transcendence (Wong, 2016). Such an educated people would also have the wisdom to elect a government that both protect people’s inalienable rights for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and take care of those who are vulnerable.

References

- Dostoevsky, F. (2003). The brothers Karamazov. New York, NY: Bantam Books. Original published 1880.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Tolstoy, L. (1998). War and peace (L. & A. Maude, trans.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Original published 1869.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1979). Frustration, exploration, and learning. Canadian Psychological Review, 20, 133-144.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1995). A stage model of coping with frustrative stress. In R. Wong (Ed.), Biological perspectives on motivated activities (pp. 339-378). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Self-Transcendence_A-Paradoxical-Way-to-Become-Your-Best-2016-Aug-15.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P., Ivtzan, I., & Lomas, T. (2016). Good work: A meaning-centred approach. In L. G. Oades, M. F. Steger, A. Delle Fave, & J. Passmore (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of the psychology of positivity and strengths-based approaches at work (pp. 0-0). West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2017). The many faces of poverty. A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith (ch. 16).