The Old Paradigm is No Longer Working

The WHO World Mental Health Survey (WMH) shows that trauma exposure is common; about 70% of people experience lifetime traumas. If untreated, trauma leads to depression, PTSD, and suicide.

Suicide rates in the U.S. have increased nearly 30 percent in less than 20 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and prevention. Suicide among ages 10-24 was the second leading cause of death (2016 CDC WISQARS). These heart-wrenching statistics have received intense media coverage and national debates regarding the causes and solutions.

Although depression is a major cause of suicide, CDC pointed out in its report that more than half of the suicide related deaths in the U.S. were not previously diagnosed with a mental disorder. The medical model of having more psychiatrists, more diagnoses, and more medications has not stopped the rising rates in suicide, drug overdoses, and depression. Therefore, we need to search more broadly for the underlying cultural and social factors that contribute to suicide, overdoses, and depression.

Culture’s Role in Mental Illness

The National Academic Press (2002) on Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative has this to say: “Society and culture play an enormous role in dictating how people respond to and view mental health and suicide…Cultural variables have a far-ranging impact on suicide. They shape risk and protective factors as well as the availability and types of treatment that might intervene to lessen suicide.”

Given the importance of culture, we need to ask ourselves: Why is addiction primarily a problem with Western affluent societies? My hypothesis is that the pursuit of personal happiness and success may have contributed to our existential crisis of inner emptiness, loneliness and anxiety – the common factors underlying the current epidemic of addiction, depression, and suicide.

Our cultural obsession with happiness has unwittingly resulted in the “unhappiness epidemic” because of spending too much time on social media and smartphones, according to research by Twenge. In a national study, she found that “teens who spent more than five hours a day online were twice as likely to be unhappy as those who spent less than an hour a day.”

In her book iGen (2016), Twenge shows that those born in the mid-1990s up to the mid-2000s spend their entire adolescence on smartphone and social media, contributing to their unprecedented levels of anxiety, depression, and loneliness.

In a similar vein, Brock Bastian’s (2018) book, The Other Side of Happiness: Embracing a More Fearless Approach to Living provides considerable evidence that conforming to the social pressure of pursuing happiness and avoiding pain has created a cuddled generation, vulnerable to hardships and mental illness.

Available research indicates that several cultural-social factors have contributed to the rise in drug overdose and suicide:

- Loss of protective factors, such as religion, faith community, or a stable home,

- Increase in the use of smart-phones and social media results in a decrease in genuine face-to-face relationships.

- Lack of psychological preparedness and coping skills for life’s inevitable problems.

- Unrealistic expectations of happiness, beauty, and success.

The resulting alienation (loneliness), helplessness, anxiety, hopelessness, and meaninglessness contribute to the epidemic of depression, addiction, and suicide, as predicted by Viktor Frankl (1985).

Therefore, at both the societal and individual levels, to avoid the happiness trap, we need to develop a more realistic life orientation and focus on what really matters in life, such as developing loving relationships, making personal sacrifices for something bigger than oneself, and having faith in a higher power or transcendental values, all protective factors against depression and suicide

A New Narrative is Needed to Combat Mental Illness

In contrast to the dominant message of American positive psychology that emphasizes what is good and right in life, the message of existential positive psychology (PP 2.0) (Wong, 2011, 2016) and meaning therapy is that life is full of suffering and injustice. We need to give up our unrealistic expectations of only good things and confront life with a sense of tragic optimism and struggle for a better future with courage. Paradoxically, more recent research has shown that such a realistic life orientation actually increases our capacity for resilience and happiness.

Contrary to the popular belief that we should avoid painful emotions, all our efforts to protect ourselves against suffering actually make us more vulnerable to life’s problems and mental illness. That is why I advocate the radical acceptance of personal responsibility to face suffering with courage.

My recent book on Inspirations for Difficult Times (2019) was designed to change the national conversation from hedonic pursuits, to a less travelled road of mature happiness, based on embracing tragic optimism, a meaning-mindset, courage, self-transcendence, and life intelligence in overcoming life’s many problems. The book also describes the basic steps to returning to the core values of faith, love, and meaning, the positive triad which has powered human beings to survive and flourish since the age of antiquity in spite of adversities.

Another book that supports the new narrative is Kelly McGonigal’s (2015) book on The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It. McGonigal highlights new research indicating that stress can, in fact, make us stronger, smarter, and happier, if we learn how to cultivate the power of beliefs and embrace stress as source of energy.

The Meaning Therapy Solution

We have a serious mental health crisis, because we are like the fish out of water, living in a materialistic consumer society and a digital world without paying much attention to our spiritual needs. Technological progress contributes to our physical wellbeing, but it also destroys the soul if we do not make an intentional effort to care for our soul.

Meaning Therapy helps people get back into water—to meet people’s basic psychological needs for loving relationships, meaningful work, faith in God, and some transcendental values.

In times of life crisis, collective madness and an uncertain future, we need to get back to the basics of:

- Faith in God or spiritual core values

- Love for people and develop relationships

- Meaning in one’s work and pursuits.

This positive triad has enabled humanity to survive since the beginning of time; it is still essential in overcoming depression, addiction and suffering and creating a better future.

Paradoxically, meaning therapy teaches the basics of positive mental health — radical acceptance of suffering with courage, a return to the core values of faith, love and meaning and the life intelligence of coping with the adversities and vicissitude of life.

The Meaning Therapy Innovation

Meaning therapy is innovative in many ways. The most important departure from traditional practices of psychology is that meaning therapy advocates a pluralistic and integrative approach. It is opposed to the prevailing tribal or silo mentality; it believes that the more we collaborate and work together, the faster we can resolve the mental health crisis.

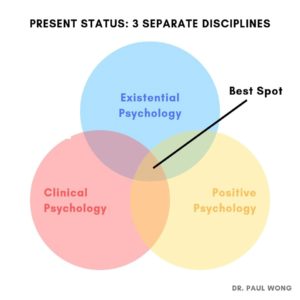

This figure on the left represents the current situation. There is only limited cooperation and overlaps in the three discipline. One may substitute existential psychology with religion, or replace clinical psychology with psychiatry, but the situation remains the same – they all operate as separate disciplines.

I propose the best spot for effective psychotherapy is the small common core, where the therapist is able to address a client’s existential crisis, psychological disorders, and basic need for happiness and meaning in the same clinical session.

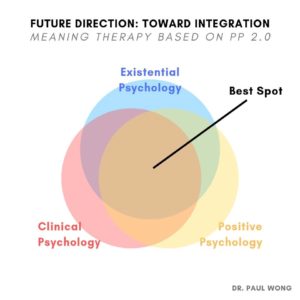

In contrast to the current practice, I have attempted to increase the common core as shown in the next figure below.

There are at least three reasons for this movement towards integration:

- Clinical psychology and positive psychology are inadequate in and by themselves; they really need each other to be complete. It is like the synthesis that emerges from both the thesis and antithesis, as I have argued for PP 2.0.

- Existential psychology has to do with the condition of human existence, relevant to all people. Therefore, it is impossible for any psychotherapist to totally ignore the client’s existential concerns. I have argued that all psychotherapists need to have existential competency.

- The existential givens include both the basic primitive emotions of shame, guilt, and fear, and the basic emotional needs for faith in something stronger than oneself, relational support. and meaning (both symbolic meaning and objective values for the human community to survive).

In the first part of my meaning therapy workshop at Ottawa’s Royal Health Centre, I will explain how these disciplines can be integrated in service of clients’ well-being. In the second part of meaning therapy workshop in Toronto during July, I will focus on how integration can help transform traumas into strengths and resilience.

The Impact of Meaning Therapy

My meaning-focused research and therapy has been cited more than 14,000 times. My Personal Meaning Profile has been widely used. The implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the personal meaning profile have been cited more than 500 times. My first journal article on “Meaning Therapy: An Integrative and Positive Existential Psychotherapy” (2010) has also been widely cited. Here is a list of most recent citations of this paper alone; this small sample indicates meaning therapy’s broad impact on different approaches to psychology:

- Leontiev, D. (in press). The dialectics of aloneness: Positive vs. negative meaning and differential assessment. Counselling Psychology Quarterly.

- Leung, M. M. (2019). Tragic optimism: an integrative meaning-centred approach to trauma treatment. Counselling Psychology Quarterly.

- Zhang, R. (2019). Quest for a pathway to human’s good life in the Chinese cultural context. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1634002

- Lincoln, J., & Hoffman, L. (2019). Toward an integration of constructivism and existential psychotherapy. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 32(2), 108-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2018.1461719

- Niemiec, R. M. (2019). Six functions of character strengths for thriving at times of adversity and opportunity: A theoretical perspective. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 14(53), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9692-2

- Flora, K. (2019). Second wave of positive psychology: Beyond the dichotomy of positive and negative and the consequences in the practice of psychotherapy. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1573165

- Dakwar, E., Nunes, E. V., Hart, C. L., Hu, M. C., Foltin, R. W., & Levin, F. R. (2018). A sub-set of psychoactive effects may be critical to the behavioral impact of ketamine on cocaine use disorder: Results from a randomized, controlled laboratory study. Neuropharmacology, 142, 270-276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1633497

- Cohen-Scali, V., Rossier, J., & Nota, L. (Eds.). (2018). New perspectives on career counseling and guidance in Europe. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

- Russo-Netzer, P. (2018). Prioritizing meaning as a pathway to meaning in life and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0031-y

- Testoni, I., Sansonetto, G., Ronconi, L., & Rodelli, M. (2018). Meaning of life, representation of death, and their association with psychological distress. Palliative and Supportive Care, 16(5), 511-519. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951517000669

- Vidon, E., & Rickly, J. (2018). Alienation and anxiety in tourism motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 69, 65-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.02.001

- Lamis, D. A., & Kapoor, S. (2018). Childhood sexual abuse and suicidal ideation among bipolar patients: Existential but not religious well-being as a protective factor. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12438

- Aviad-Wilchek, Y., Ne’eman-Haviv, V., & Michal. (2017). Connection between suicidal ideation, life meaning, and leisure time activities. Deviant Behavior, 3(6), 621-632. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2016.1197590

- Bellin, Z. J. (2017). Attending to meaning in life in the lives of marginalized individuals. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56(3), 211-227. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12054

- Hill, C. E. (2017). Therapists’ perspectives about working with meaning in life in psychotherapy: A survey. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 30(4), 373-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2016.1173014

- Rayner, M., & Vitali, D. (2016). Existential experimentation: Structure and principles for a short-term psychological therapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 58(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167816655925

I firmly believe that PP 2.0 represents the future of psychology, and meaning therapy represents the future of psychotherapy. That is why I am still working day and night in spite of my old age and ongoing battle with cancer. I sincerely invite you to join me at the INPM so that we can work together to move forward psychology forward for the benefit of humanity in this critical juncture of human history.

References

- Bastian, B. (2018). The other side of happiness: Embracing a more fearless approach to living. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

- Twenge, J. M. (2019). Generation me (Revised and updated ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9132-6

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Inspirations for difficult times. (This book could be purchased here. First presented at the Ottawa Royal Mental Health Center, Canada.)

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2019, July 16). The current mental health crisis and meaning therapy. Presented at Ottawa’s Royal Mental Health Center, Canada. Retrieved from https://www.meaning.ca/article/the-current-mental-health-crisis-and-meaning-therapy/

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.