Authors

Co-authored with Timothy Reilly, Ph.D., Dept. of Psychology, University of Notre Dame

Abstract

This presentation will conclude my research project on Viktor Frankl’s self-transcendence (ST) model as a framework of applying virtue ethics. My focus in this presentation is to explain why Frankl’s ST model provides a useful ethical framework for living and behaving well and how it is consistent with the Aristotelian and Thomistic moral theory of virtue ethics in important ways.

Virtue is an important topic for psychology, philosophy, and business management because it is concerned with moral excellence and ethical behaviours that are crucial for the well-being and flourishing of individuals and communities. The real challenge for any moral theory is whether it has the practical value of helping people live as ethical, decent human beings in daily concrete situations.

Frankl’s ST model is very practical because it was the result of wrestling with the ethical challenges of how to be a decent human being under two very difficult conditions in real life. The first challenge was how to live with a sense of human dignity and significance even when one was facing unimaginable degradation, atrocities, and a cruel death; the other challenge was how to prevent anyone in a position of power from becoming a monster like Hitler.

Frankl’s answer to the above two ethical challenges is threefold: (1) to awaken the will to meaning to search for ST (i.e., the spiritual and noble part of human nature); (2) to practice the meaning-mindset to discover the truth, beauty, and goodness in all life’s situations, no matter how bad (i.e., the need for a perspective shift); (3) and to cultivate personal responsibility to choose and do the right thing in every situation, (i.e., the good habit of following one’s innate conscience and the time-tested moral norm). I will explain how these three practices facilitate one’s character development based on practical wisdom, acquired virtues, and infused virtues, resulting in a good life that is consistent with one’s spiritual and moral nature.

Introduction

The main thesis in this presentation is that Viktor Frankl’s self-transcendence (ST) model provides a useful ethical framework for living and behaving well. We also argue that his model is consistent with the Aristotelian and Thomistic moral theory of virtue ethics in important ways (Hursthouse & Pettigrove, 2016).

Virtue is an important topic for psychology, philosophy, and business management because it is concerned with moral excellence and ethical behaviours that are crucial for the well-being and flourishing of individuals and communities. The real challenge for any moral theory is whether it has the practical value of helping people live as ethical, decent human beings in daily concrete situations.

Frankl’s ST model is very practical, because it was developed and tested in wrestling with the ethical challenges of how to be a decent human being under two extremely difficult conditions in real life. The first challenge had to do with suffering—how to live with a sense of human dignity and significance even when one was facing unimaginable degradation, atrocities, and a cruel death. The second challenge had to do with power—how to prevent anyone in a position of power from its corrupting influence and becoming a monster like Hitler.

Summary of Previous Presentations

At the first Virtue Scholars meeting, I presented the meaning hypothesis of living a good life (Wong, 2015a), based on my interpretation of Frankl’s concept of meaning-seeking (Wong, 2014) and his ST model (Wong, 2016a). More specifically, the meaning hypothesis posits that our primary motivational need of seeking meaning (i.e., the will to meaning) and the meaning-mindset of finding meaning (i.e., meaning of life) constitute the motivational and cognitive factors of ST. My focus was on the importance of the perspective of the meaning-mindset.

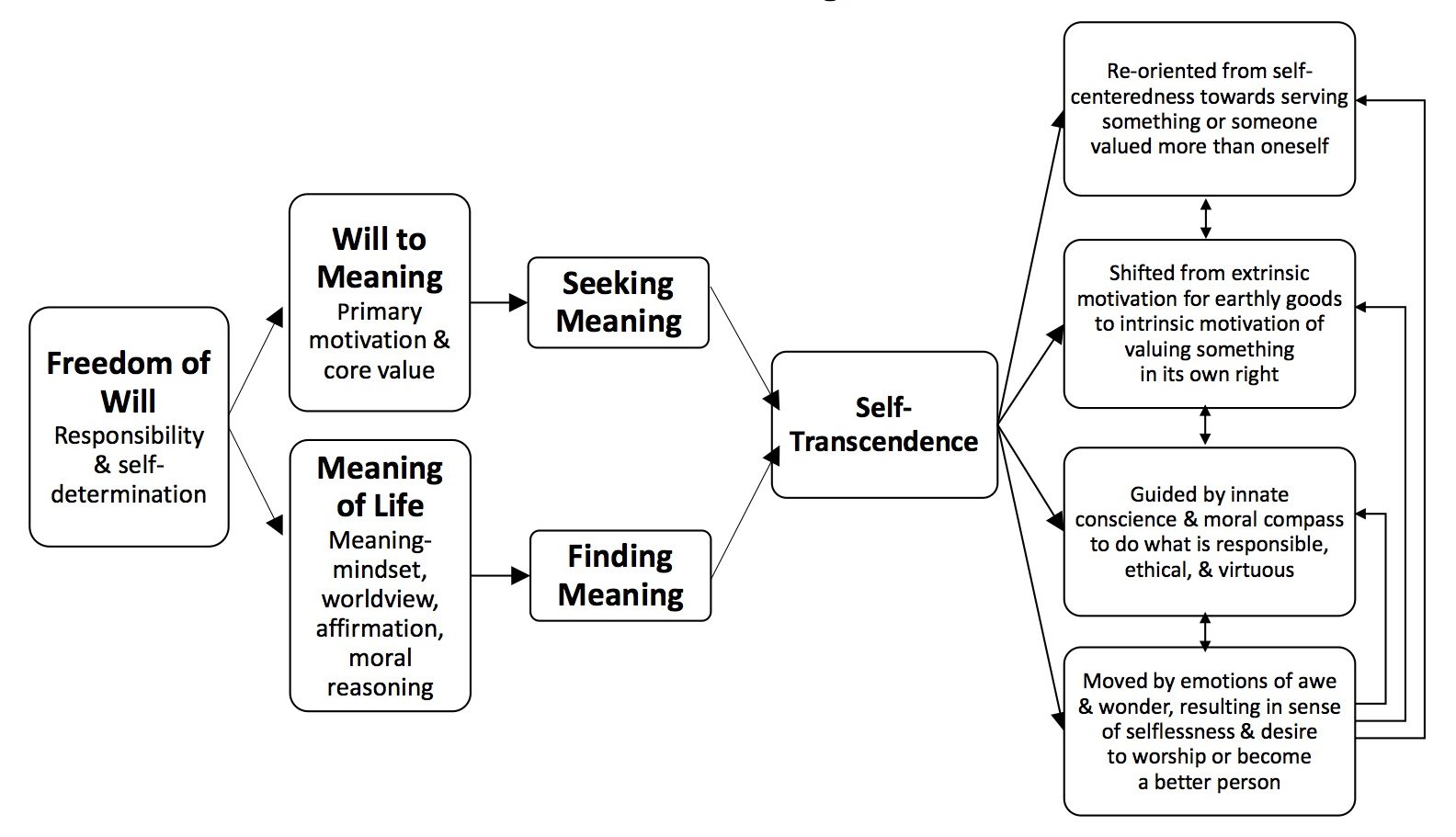

Figure 1. Frankl’s two-factor theory and characteristics of self-transcendence.

My second presentation elaborated on the meaning hypothesis by explaining how the striving towards some goals of ST is a promising pathway to live a good life of virtue, happiness, and meaning (Wong, 2016b). My focus was on the motivational aspect of seeking meaning. After reviewing various conceptions and models of ST, I concluded that Frankl’s two-factor model of ST (cognitive and motivational factors) represents the most comprehensive ST model for research and intervention.

At the last Virtue Scholars meeting, I sketched the various components of Frankl’s ST model and their inter-relationships as shown in Figure 1. I also introduced the four defining characteristics of ST as measured by the Self-Transcendence Measure (STM) (Wong, 2016c). I proposed that these four dimensions could differentiate the virtuous type of genuine ST from the evil type of pseudo-ST because of their inherent moral orientation (Wong, 2017).

In this present paper, the focus is on the basic tenets of Frankl’s ST model and their moral implications for living a virtuous life. We attempt to integrate Frankl’s work with moral philosophy.

Basic Assumptions of Frankl’s Self-Transcendence Model and Virtue Ethics

Frankl’s answer to the two ethical challenges identified in the introduction is fourfold: (1) the defiant power of the human spirit; (2) the capacity for freedom and responsibility; (3) the primary motivation for ST; and (4) the power of the meaning-mindset.

Defiant Power of the Human Spirit

Viktor Frankl (1985) described the defiant power of the human spirit as the freedom to take a courageous stance towards fate and the human capacity to transform a tragedy into a triumph. He defined courage in terms of the noetic or spiritual dimension; thus, moral courage had a spiritual origin.

Recently, Wong (2015b) interpreted the defiant power as the moral courage to maintain one’s cherished values and human dignity in the face of suffering and death; this courage is the key to true grit in surviving constant and unimaginable assaults on one’s physical and psychological integrity.

Without such moral fortitude in the face of danger, we would not be able to have the character strength to preserve and realize the moral values that make us decent human beings. This is essentially an existential courage that enables us to take a defiant stand against a harsh fate and do what is morally right despite personal dangers.

Frankl’s view of courage is consistent with both the classic and Catholic conceptions of courage as a virtue. Plato (1894/2000) considers courage as one of the four cardinal values. Aristotle (Nicomachean Ethics, 3.6-9) defines courage as have the right “amount” of fear (“the mean”); thus, a courageous person still fears things that all human beings are afraid of, yet has the courage to face these fears as one should for some good and worthy goal, such as facing death in a battle to protect one’s country. Thomas Aquinas considers fortitude or courage primarily in terms of endurance with firmness. He says, “The principal act of courage is to endure and withstand dangers doggedly rather than to attack” (Summa Theologica, IIb, 123.8). Courage is expressed when an individual is pursuing a difficult or dangerous goal that is sufficiently valuable to be worth the difficulty or danger.

In sum, having moral courage is a prerequisite for doing the right thing or making the right choice. It is easy to do what is expedient, but it takes courage to do what is right. It is an easy way out to compromise or surrender in the face of great danger, but it takes great courage to stand up for one’s core values and beliefs. Thus, moral fortitude is just the starting point; there are additional conditions one must fulfill in order to be a fully functioning decent human being.

Capacity for Freedom and Responsibility

“Freedom of will” figures prominently in Frankl’s ST model. His model hinges on the responsible use of freedom in all situations. In Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl, 1985), he declares:

Man is not fully conditioned and determined but rather he determines himself whether he give in to conditions or stands up to them. In other words, man is self-determining. Man does not simply exist but always decides what his existence will be, what he will become in the next moment. By the same token, every human being has the freedom to change at any instant. (p. 154)

Every person has the freedom and responsibility to choose their own pathway and life goals. Their choices determine their character, well-being, and destiny, even when we factor in fate or luck. Every situation presents us with the choice between good and evil, between acting on the bright side or the dark side of our nature; we can choose between spiritual joy and carnal pleasures, between practicing kindness and abusing our powers.

Shantall’s (2004) research on Holocaust survivors supports Frankl’s thesis on moral responsibility. Here are some important lessons from Holocaust survivors:

Their active efforts to maintain moral values in the face of the onslaught against them, made their lives take on greater spiritual content and meaning. Living with a profound value-directedness and moral responsibility, they experienced a sense of true destiny (something or someone to live or survive for) with peak moments of triumph and even joy. (p. 3)

The human capacity for freedom of will allows us to deliberate and choose between good and evil, between desires and values. Our awareness of the moral implications of our choices makes us morally responsible for our decisions and actions. Aquinas attributes this freedom to our rational or volitional abilities. Even though our nature may predispose us to certain ends, we have the freedom to choose between the ends, as well as the pathway to achieve a certain end. Aquinas conception of freedom, however, does not entail that all choices are equal, but rather a teleological notion of freedom- the more free one is the more able one is to pursue the good (Titus & Moncher, 2009). Another way to phrase this is that the virtuous individual is free to be just, and so to fulfill their obligations and responsibilities, choosing the proper actions for the proper reasons (Titus, 2016).

Frankl’s ST model represents an agent-centered moral theory which emphasizes the human being as a moral agent (Harris, 1999; Slote, 2001). For Slote (2001), a virtuous life depends on both a particular agent’s inner dispositions and actual motives. Therefore, the virtuous kind of ST needs to stem from a good inner disposition and a good motive.

Frankl’s model recognizes human beings as both moral and instrumental agents. It is consistent with the psychological literature of self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1977), which are predicated on the human capacity for freedom and responsibility. In moral psychology, research on moral identity (Colby & Damon, 1992) and moral education (Bebeau, Rest, & Narvaez, 1999) emphasizes that individuals whose moral goals and values are central to their self-concept feel responsible for acting in consistently moral ways.

Motivation of Searching for Self-Transcendence

The will to meaning represents the primary motivation to seek for meaning, defined as something that is greater than oneself and that is worthy of one one’s commitment to pursue. Frankl took pains to emphasize that this something cannot be totally subjective and arbitrary, because it may lead to a misguided ambition and the abuse of power. Thus, what is good and worthy must be consistent with our higher purpose and based on some objective standard of values and norms, such as not harming others and contributing to the well-being of others.

Frankl’s will to meaning represents the noble or spiritual side of human nature. It is similar to Aquinas’ (1925) description of people’s noble innate desire for what is good and choice-worthy as an end value (ST Ia 82.1; QDV 3.22.12). According to Aquinas, a virtuous person develops a virtuous disposition of living ethically through both the acquired virtue of practicing good habits and infused virtues through an awakening of one’s spiritual virtue of faith, hope, and love.

A virtuous or good habit comes from consistently doing the right thing based on following one’s reasoning and one’s innate conscience. However, both the virtuous character and a virtuous deed begin with a conscious choice to act responsibly and live responsibly according to a higher noble purpose. Thus, Aquinas contends that the virtuous individual is charitable, properly ordering their desires so that they can effectively pursue the most important ends, directing their lives toward human flourishing (Titus 2016). Narvaez’s (2016) Triune Ethics Metatheory, taking a similar approach, posits that moral motives emerge when individuals’ motivations stem from a communal imagination, prioritizing the common good rather than selfish or self-protective motives.

Thus, the virtuous kind of ST is based on (1) the responsible choice of the will to meaning rather than the will to pleasure or power; and (2) the responsible choice of doing the right thing in each situation. Such consistent choice will eventually result in a virtuous disposition.

Power of the Meaning-Mindset

Courage, responsibility, and the search for ST need to be guided or governed by the proper use of intellect (i.e., right thinking) in order to do the right thing and live a virtuous life. In other words, when one’s reason is misguided or distorted, one will not be able to choose according to one’s noble purpose and good end.

For Frankl, one’s proper use of intellect depends on believing that there is inherent meaning in human existence and specific situations. This belief or worldview is just as rational as the belief or presupposition held by scientists that the world is orderly and governed by scientific laws. Wong (2011) refers to such affirmation of meaning as the meaning-mindset.

More specifically, through the lens of the meaning-mindset, we discover both ultimate meaning and specific meanings. Ultimate meaning has to do with one’s commitment to spiritual and existential meaning. It is concerned with one’s global belief regarding the larger schemes of things: “This grandiose order, I believe, is what Frankl understands by logos, ultimate meaning. We can never hope to ‘find’ it in its totality, we can only pursue it to the best of our abilities” (Fabry, 1994, p. 35).

Frankl (1985) believes that it is more productive to address the specific meanings of the moment, because ultimate meanings exists in the supra-human (or supernatural) dimension and is “hidden” from us. However, ultimate meaning is important in shaping our perceptions and actions; specific meanings of the moment cannot be separable from our assumptions about ultimate meaning, just as figures are perceived as part of the ground. William James said, “Believe that life is worth living, and your belief will help create the fact” (as quoted in Bridges, 1916, p. 425). Therefore, the belief in ultimate meaning facilitates the discovery of specific meanings.

The other aspect of the meaning-mindset is to assess each situation in terms of its meaning potentials. In each situation, cognitive meaning refers to causal attribution and stress appraisal; existential meaning refers to its reason or purpose for a responsible action. Such reasoning is guided by knowledge and logic, but, equally important, it is also guided by one’s innate conscience and moral norms. There is the challenge to make the right decision without complete information; but responsibleness demands that our action be helpful to others and fit into larger patterns of ultimate meaning. Although Frankl is aware that different cultures may have different moral norms and emphasize different virtues (MacIntyre, 1985), he believes in the inner voice of “oughtness,” similar to Kant’s (1785/1993) concept of “categorical imperatives”—we ought to care for others and contribute to the common good, consistent with our higher calling.

Frankl’s understanding of reason is similar to Aquinas’ concept of reason as a species-defining characteristic and his thesis that the proper exercise of will results in human goodness to the extent that one’s action is consistent with our worthy end and infused virtues. Frankl’s situational meaning is also consistent with Aristotle’s practical wisdom, because our action is appropriate to the demand characteristic of the situation.

Practical wisdom means that, in addition to responsible choice (willing to do what is right), the virtuous person also knows how to do what is right in a particular situation for a person such as themselves (Titus, 2016). Knowing how to do what is right includes prioritizing various choices one has made properly. For instance, while eating is important, it is generally more important to help someone experiencing a medical emergency than to eat. Further, if one doesn’t have the opportunity to eat, as in a situation of deprivation, a practically wise individual will respond appropriately rather than being distracted excessively by hunger. Practical wisdom also generally entails that an individual will seek to develop capacities relevant to their situation and that they will choose means in which they are competent to achieve the good (e.g., not attempting risky medical procedures without training). Practical wisdom serves to integrate, develop, and enact an individual’s virtues.

Conclusion

We have explained why Frankl’s four basic tenets—courage, responsibility, meaning-seeking, and meaning-finding—have moral implications similar to the Aristotelian and Thomistic moral theory of virtue ethics in important ways.

Frankl’s model provides a practical framework to live a virtuous life of ST with a philosophical foundation in virtue ethics. Although Frankl avoided being identified as religious, his emphasis on faith in a level of ultimate meaning or supra-meaning acknowledged a transcendental source of our moral responsibility and virtuous behaviour: “Being human is being conscious and being responsible, culminating in a synthesis of both, namely, one’s consciousness of his responsibleness” (Frankl, 1975, p. 60).

In other words, living a virtuous life does not solely depend on cultivating the habit of doing good deeds until it leads to the development of a character of virtue; it also depends on being awakened to and cultivating our spiritual motivation to pursue ST and our consciousness of our ethical responsibleness in every situation. The pursuit of goodness, beauty, and truth can be facilitated by awakening our true spiritual nature of faith, hope, and love. Thus, Frankl’s two-factor theory of ST is similar to Aquinas’ emphasis on both acquired virtues and infused virtues.

Another advantage of Frankl’s ST model is that he has interventions designed to practice the above four virtues. For example, courage can be increased by paradoxical intention and responsibility can be enhanced through Socratic questioning. Similarly, de-reflection can be used to redirect one’s attention from self-absorption to some activity of ST. The practice of the meaning-mindset can be facilitated by self-distancing and mindfulness.

References

- Aquinas, T. (1911-1925). Summa theologica. New York, NY: Benziger Brothers.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

- Bebeau, M. J., Rest, J. R., & Narvaez, D. (1999). Beyond the promise: A perspective on research in moral education. Educational Researcher, 28(4), 18-26.

- Bridges, R. S. (Ed.). (1916). The spirit of man: An anthology. New York, NY: Longmans Green.

- Colby, A., & Damon, W. (1992). Some do care: Contemporary lives of moral commitment. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Fabry, J. B. (1994). The pursuit of meaning (Rev. ed.). Abilene, TX: Institute of Logotherapy Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1975). The unconscious God. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Harris, G. W. (1999). Agent‐centered morality: An Aristotelian alternative to Kantian internalism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hursthouse, R., & Pettigrove, G. (2016). Virtue ethics (Rev. ed.). In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/

- Kant, I. (1993). Grounding for the metaphysics of morals: On a supposed right to lie because of philanthropic concerns (J. W. Ellington, Trans.; 3rd ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett. Original published 1785.

- MacIntyre, A. (1985). After virtue: A study in moral theory (2nd ed.). London, UK: Duckworth.

- Narvaez, D. (2016). Embodied morality: Protectionism, engagement, and imagination. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Plato. (2000). The republic (J. T. Pine, Ed.; B. Jowett, Trans.). Mineola, NY: Dover. Original published 1894.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Shantall, T. (2004). The defiant power of the human spirit: Lessons from the Holocaust in addressing ideological violence and crime in contemporary society. Workshop presented at the Fourth International Conference 2004 of the International School for Holocaust Studies, Jerusalem, Israel.

- Slote, M. (2001). Morals from motives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Titus, C. S. (2016). Aquinas, Seligman, and positive psychology: A Christian approach to the use of the virtues in psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1228005

- Titus, C. S., & Moncher, F. (2009). A Catholic Christian positive psychology: A virtue approach. Edification: Journal of the Society for Christian Psychology, 3(1), 57-63.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). Viktor Frankl’s meaning seeking model and positive psychology. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in existential and positive psychology (pp. 149-184). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015a, December). The meaning hypothesis of living a good life: Virtue, happiness, and meaning. Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). The positive psychology of grit: The defiant power of the human spirit [Review of the film Unbroken]. PsycCRITIQUES, 60(25). doi:10.1037/a0039390

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Meaning-seeking, self-transcendence, and well-being. In A. Batthyany (Ed.), Logotherapy and existential analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute (Vol. 1; pp. 311-322). Cham, CH: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b, June). Self-transcendence as the path to virtue, happiness and meaning Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016c, December). From Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy to the four defining characteristics of self-transcendence. Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, Columbia, SC. (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation).

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017, January 18). The varieties of self-transcendence: The good and the bad. Positive Living Newsletter. Retrieved from www.drpaulwong.com/inpm-presidents-report-january-2017

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., & Reilly, T. (2017, August 15). Frankl’s self-transcendence model and virtue ethics — Part 1 of 2. The Virtue Blog. Retrieved from https://thevirtueblog.com/2017/08/15/frankls-self-transcendence-model-and-virtue-ethics-part-1-of-2/ (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

Wong, P. T. P., & Reilly, T. (2017, August 16). Frankl’s self-transcendence model and virtue ethics — Part 2 of 2. The Virtue Blog. Retrieved from https://thevirtueblog.com/2017/08/15/frankls-self-transcendence-model-and-virtue-ethics-part-2-of-2/ (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.