Introduction

The present paper continues my earlier presentation on self-transcendence (ST) as a pathway to meaning, virtue, and happiness (Wong, 2016), in which I introduced Viktor Frankl’s (1985) two-factor theory of ST. Here, the same topic of ST is expanded by first providing the basic assumptions of logotherapy, then arguing the need for objective standards for meaning, and finally elaborating the defining characteristics of ST.

To begin, here is a common-sense observation—no one can remain at the same spot for life for a variety of reasons, such as developmental and environmental changes, but most importantly because people dream of a better life and want to move to a preferred destination where they can find happiness and fulfillment.

As a psychologist, I am interested in finding out (a) which destination people choose and (b) how they plan to get there successfully. In a free society that offers many opportunities for individuals, there are almost endless options regarding both (a) and (b).

The reality is that not all purposes in life are equal. Some life goals are misguided, such as wanting to get rich by any means, including unethical and illegal ones, because ultimately, such choices could be self-defeating—these end values might not only fail to fill their hearts with happiness, but might also ruin their relationships and careers.

The question, then, is: What kind of choices will have the greatest likelihood of resulting in a good life that not only benefits the individual but also society? My research has led me to hypothesize that the path of ST is most likely to result in such a good life. More specifically, I propose that Frankl’s two-factor theory of ST provides a promising roadmap for achieving ST.

According to Frankl, the pursuit of ST offers the most promising path to live a life of virtue, happiness, and meaning. This way of life not only develops our character strengths and virtue, but also increases our capacity for healing and flourishing. There is increasing empirical support for this hypothesis (Wong, 2012; Batthyany & Russo-Netzer, 2014).

Historical Context

The following historical context of Viktor Frankl’s work is provided for one to better understand Frankl’s account of ST, which is at the heart of logotherapy. When Frankl was developing his logotherapy, he wrestled with two urgent practical issues:

- How to restore human dignity and value amid the degradation, suffering, and death in the Nazi concentration camps.

- How to prevent another Hitler and Holocaust from happening again.

At the same time, Frankl was also waging an intellectual battle against psychoanalysis and behaviourism, the two dominant schools of psychology at that time, for their deterministic thinking. Frankl maintained that human beings always have the capacity of free will in all situations despite the environmental and genetic factors that shape their behaviour.

Therefore, both Frankl’s logotherapy and his theory of ST reflect his deep concern regarding the above issues. Without this historical footnote, it is difficult to understand why he put so much emphasis on personal responsibility.

Three Inter-Related Basic Assumptions of Logotherapy

Freedom of Will

Freedom of will is the central piece in Frankl’s conceptual framework. Freedom and responsibility go hand in hand; without responsibility, there will be anarchy, and society will disintegrate.

Frankl emphasized that freedom of will is the essence of human existence; it is the inevitable first principle. Human beings ought to act in an ethical and responsible way towards others as well as the demands of life. This “oughtness” within is similar to Kant’s moral obligation (McCormick, n.d.). Thus, no one can justify the killing of millions of innocent people for the sake of ethnic cleansing. Frankl believed that this kind of moral teaching, when widely accepted and implemented, would help prevent genocide and the perpetuation of atrocities against other human beings.

He coined the term “response-ability” in lieu of responsibility. While responsibility has the connotation of an external authority dictating that one should do this or that, “response-ability” has the connotation of an inner moral obligation that you ought to do this or that. In other words, “response-ability” sounds like a categorical imperative for all human beings as moral agents.

Thus, every person ought to tell themselves: “Don’t ask what you can get from life, but ask what life demands of you.” In struggling with the persistent question about the meaning of life, the answer does not come from inside the individual, but from something outside the individual, be it God, country, or life as a whole. To discover meaning demands a re-orientation towards the outside world, because people do not exist as individuals bound in their own skin; they are an integral part of a relational world.

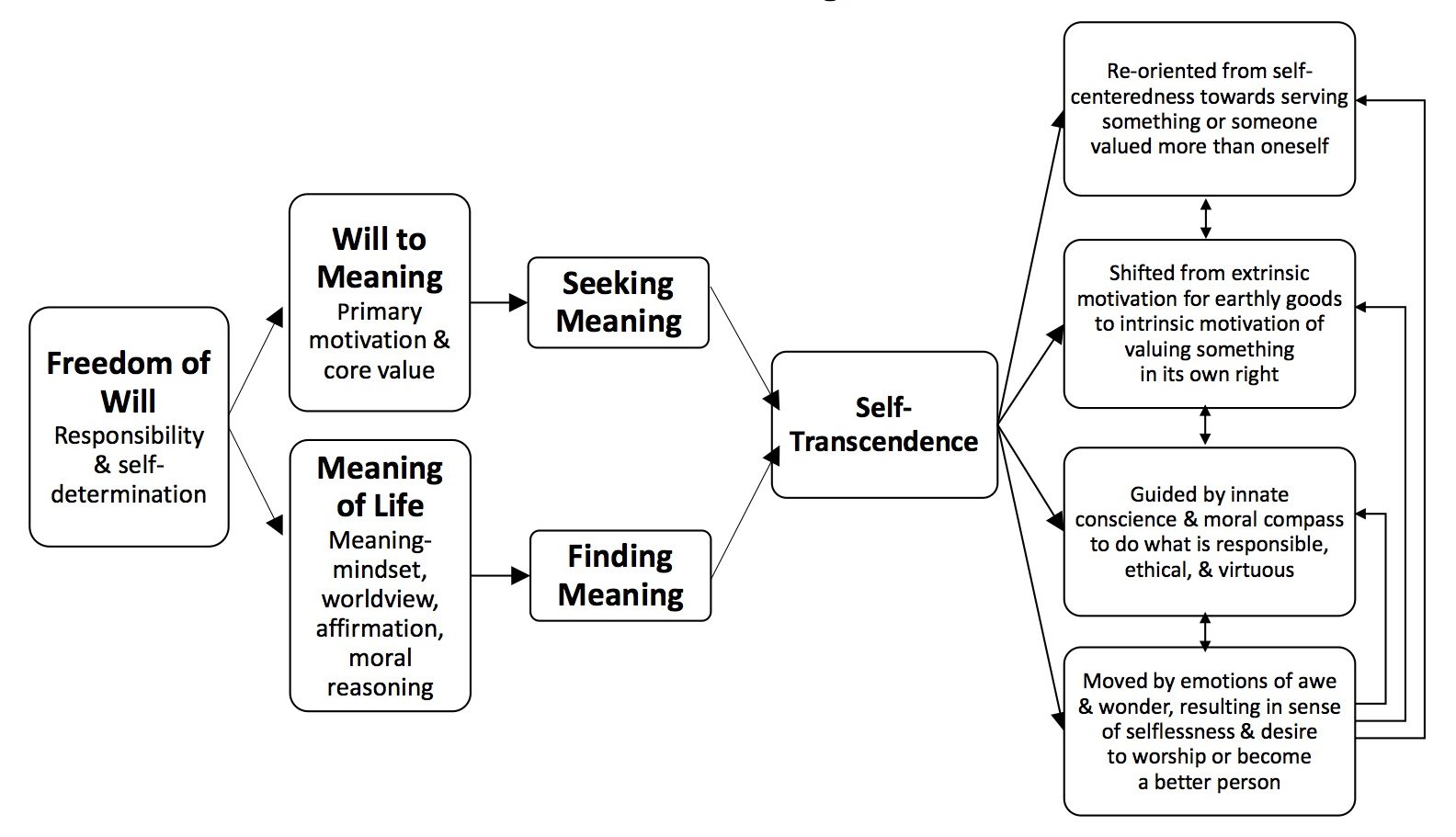

Given the central role of freedom and responsibility, this point should be the source of two other points: the will to meaning and meaning of life in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Frankl’s two-factor theory and characteristics of self-transcendence.

Will to Meaning

All people have the capacity to exercise their volition. They can either choose to orient themselves towards the will to pleasure, the will to power, or the will to meaning.

The will to meaning represents a noble motivation, rooted in the spiritual or noetic dimension of human nature. It motivates us to pursue meaning, or more precisely, ST. We are naturally inclined towards ST because we are either created or hardwired to love God and love others. It is only in fulfilling these two spiritual needs for connecting with and serving something greater than ourselves that we can experience meaning, virtue, and happiness.

In fact, according to Frankl, we become truly human beings only when we exercise volition and choose to orient ourselves to the will to meaning. This is in contrast to the baser motivations of the will to pleasure and the will to power, which are based on instincts shared by all sub-human animals.

Meaning of Life

If we all have the innate need for meaning, and meaning is essential for our soul just as oxygen is essential for our body, it follows that we should be able to find and experience meaning everywhere. That is why we need the third tenet.

This tenet represents the cognitive factor and can be broken into three components. I have used the term meaning-mindset (MM) to encompass all the above cognitive or rational capacities that enable us to discover meaning and do the right thing in every situation.

Firstly, the MM means the worldview of global belief that there is ultimate meaning in human existence. William James, in his Harvard address said, “Believe that life is worth living, and your belief will help create the fact” (as quoted in Bridges, 1916, p. 425). Recent research has supported the hypothesis that our beliefs shape our perceptions and actions (Braaten & Huta, 2016).

Secondly, the MM is the belief or affirmation that every life has inherent meaning and that meaning can be discovered in any situation, even in Nazi death camps.

Thirdly, it entails the belief that we can be guided by our rational capacity or moral reasoning to discern what constitutes a responsible or moral response in any given situation. In other words, meaning of life entails the need to assume that we have both the personal responsibility and rational capacity to do the right thing that not only makes us feel good and but is also honorable and praiseworthy by others.

In the final analysis, meaning is not just an idea but, more importantly, the right action—it is not what you think, but what you do with your life and whether you behave in an ethical and responsible way. That is why responsibility is an essential component in Frankl’s concept of meaning of life.

Subjective vs. Objective Meaning

While admitting that it is up to each individual to discover that is meaningful, Frankl hastened to add that it also cannot be arbitrary or totally subjective. If it is completely subjective, then people like Hitler can claim to have lived a meaningful life—such argument would be adding insult to injury for the Jewish people.

Therefore, what is meaningful needs to be based on some objective and enduring values and consistent with one’s innate conscience and some normative moral standards.

- Normative ethics, like the golden rule.

- Moral principles, such as justice, truthfulness, and kindness.

- Reasonableness, whether the goal or action is reasonable or morally justifiable; it is reasonable to repel an intruder to protect one’s own family, it would not be reasonable or morally right to wipe out a whole race in order to protect the purity of one’s own race.

Frankl’s Three Sources of Objective Values

These three objective values teach us how to live a life of ST in everyday situations. These values not only make sense but can also be implemented by every person in every culture.’

Creative Value: Giving Something Back to the World. The creative value involves being purposefully engaged in productive work in a creative way. It means bringing one’s unique talent and creative ideas to any work we do in order to produce some value or good to society or makes a difference in the world.

It does not matter whether your work is associated with a role you play or a project you pursue; it also does not matter whether your work is paid or unpaid. It is a categorical imperative that you ought to be engaged in some kind of worthwhile work in order to experience some meaning in life. Even the Bible says that those who do not work should not eat. In other words, no one should occupy the land without producing any fruit.

Purpose matters more than the nature of work; if your attitude of work is to serve others or some worthy cause, you will find work more meaningful than merely working for money.

Experiential Value: Receiving Something from the World with Gratitude. The experiential value involves appreciating the loving relationships and the beauty all around us. It sensitizes us to the rainbow after a storm or the beautiful sunset after a hard day’s work.

There is plenty of empirical findings indicating that the experience of receiving love and kindness from people or the encounter of the beauty and wonders of nature and the arts is also an objective and empirically proven source of meaning and joy (Kellert, 2012; Krause, 2007; Solomon, 1976; Wong, 1998).

Attitudinal Value: Taking a Stand Towards Fate. The attitudinal value involves the defiant power of the human spirit in facing adversity with courage or moral fortitude. It is the essential component of true grit (Wong, 2014a). The stoic attitude of maintaining one’s dignity and integrity in the face of danger and hardships is the last line of defense to extract some sense of freedom and meaning.

The above three basic tenets are rooted in the spiritual or noetic dimension of human nature. They represent the better angels of human nature in contrast to the inner demons of satisfying one’s greed and need for domination through violent means.

Frankl’s Two-Factor Theory of ST

Will to Meaning as the Motivational Factor

The will to meaning is the motivational factor that moves people from point “A” towards a certain destination where ST is experienced. It was considered by Frankl as a primary motivation for meaning or ST. From the perspective of end values, ST was one of the universal values, according to Schwartz (1992, 1994). Thus, the will to meaning consists of both push and pull motivations in one’s striving towards a meaningful goal.

Meaning of Life or Meaning-Mindset (MM) as the Cognitive Factor

We can discern and discover the meaning of life through the MM; as the cognitive factor, the MM consists of one’s worldviews or assumptions affirming that life has inherent meaning and value.

If mindfulness adds clarity by regulating or reducing one’s emotional reactivity, the MM provides the lens that adds depths to one’s perception. Thus, food is more than mere a substance that satisfies one’s hunger, but the product of other people’s labour and provision from nature. The detection of meaning and significance will fill one’s heart with gratitude and humility. Similarly, the news or images of victims of war are no longer just statistics or tragic events in remote places, but the presence of evil that needs to recognized and overcome. Thus, such images of victims will trigger a sense of empathy and compassion, and may even motivate one to take actions against war and violence.

In short, the MM enables people to see things from the deeper spiritual perspective; it enables one to see the connectivity of all people and all living things, and enables people to discover the significance of ordinary events. In short, the MM facilitates the discovery of meaning and significance, and the selection of worthy life goals to pursue. The two factors work together to contribute to the discovery of ST at all three levels.

A MM opens one’s perception to all the hidden meanings in ordinary life experiences—sunsets to sunrises, the starry skies and snow-capped mountains, the spontaneous play of little children and the wrinkled smiling faces of old people—these experiences can move us with a sense of wonder and appreciation of life.

According to King and Hicks’ research (2009), one’s worldview or assumption facilitates the detection of meaning. Similarly, research also indicates that one’s worldview that life has inherent meaning facilitates goal-striving towards sacred emotions (Emmons, 2005) or eudaimonic happiness (Braaten & Huta, 2016). In addition, Haidt (2000, 2003) provides evidence that being open to the possibilities of discovering meaning and connecting with something larger increases the likelihood of awe and positive emotion of elation.

Together, these two factors contributing to the pursuit and discovery of ST, which has four defining characteristics. This two-factor theory of ST is schematized in Figure 1.

The Four Defining Characteristics of ST

However, some ST can be harmful to both individuals and humanity, such as Hitler’s grand vision of the Third Reich or a drug lord’s ambition of being the most powerful drug trafficker. Therefore, an authentic or genuine pursuit of ST needs to have the following defining characteristics.

A Shift in Focus from Self to Others

This involves a re-orientation from egotistic concerns or selfishness towards something greater or someone more valued than oneself. There is a new sense of selflessness in being connected with something vast or grand or someone more important than one’s own life. While the will to meaning provides the necessary motivation to actively engage in searching for ST, the MM provides the worldview and openness to discover something that transcends selfishness and personal limitations.

This re-orientation may happen at three levels: the transpersonal, life as a whole, and situational. At the transpersonal level, there is a perceived connection with God, nature, or all living things. There is a new openness to the spiritual/transcendental realm and the possibilities of meaning, beauty, and goodness all around us facilitates our discovery of all these ideals. At the level of life as a whole, there is an awareness of one’s worthy life purpose or the unconditional self-acceptance and affirmation that one’s life has inherent meaning and value, independent of one’s possessions or achievements. At the situational level, MM and mindful observation of life as it is happening enables us to detect the hidden meaning and significance in ordinary situations, thus, surprising us with joy and a sense of awe (Vasalou, 2015).

Awareness of major life transitions and one own mortality can shift one’s focus from preoccupation with earthly concerns to the larger schemes of things and the transcendental realm. Spiritual conversion may also shift the focus from the city of the earth of the city of heaven (Augustine, 2009; Tolstoy, 1882/1921).

A Shift in Values

This involves a shift in emphasis from extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to doing something in its own right, such as playing, doing good deeds, or caring for friends and loved ones. Such activities are not only inherently rewarding and worthwhile, but also beneficial to others and make the world a better place. One engages in ST for its own sake, rather than as an instrument to serve some other extrinsic motive. It also entails the willingness to sacrifice self-interest for serving the greater good or higher purpose.

Intrinsic motivation also means pursuing some goal that has intrinsic or inherent value—the value that is good in itself and for its own sake, such as the goal of helping others, saving lives or saving planet earth. William Frankena’s (1973) list of intrinsic value includes life, consciousness, love, virtue, justice, and all things that are morally good inherently.

These shifts in focus and values may result from a personal encounter with a life-changing event, such as surviving 9/11 or a serious illness, but also from a shift in perspective from the success orientation to the spiritual or meaning orientation as a result of reading Frankl’s books or seeing a meaning therapist.

These shifts emphasize that all people are hardwired for connecting with each other and with a higher power or cosmos; therefore, relational pursuits motivated by love and compassion are deeply satisfying to the extent they meet one’s deepest spiritual needs.

An Increase in Moral Concern

There is an increase in attention to the moral dimension in one’s goal pursuit and action. The above shifts are aligned with one’s moral compass, which includes one’s innate conscience (natural moral law), religiously- or theologically-based moral law, and some culturally-based normative vision of moral values and virtues. The cardinal virtues according to Plato and Confucius, or the normative ethics of the golden rule, are part of the moral compass that differentiates true ST from pseudo-ST, such as terrorist suicide bombers.

In addition, we are endowed with the capacity for moral reasoning. We evaluate some goals and actions as moral, when they are consistent with moral compass. Moral responsibility is important to ensure that we are sensitive to the well-being and rights of other people in our goal strivings and decision makings.

Emotions of Elevation

All the above three characteristics may trigger emotions of elevation. These emotions include awe, ecstasy, or amazement because of something extraordinary in its vastness (God or nature), ability (exceptional accomplishment), or goodness (special kindness of one person towards another). This feeling of awe is part of life-transforming experiences because it moves people towards worship or becoming a better and more responsible person.

Haidt (2000, 2003) describes the emotion of elevation as a warm, uplifting feeling that people experience when they see unexpected acts of human goodness, kindness, and compassion (Haidt, Algoe, Meijer, Tam, & Chandler, 2000). Awe, in turn, triggers in people a desire to create new mental schemas or new ways of looking at the world (Haidt & Keltner, 2004), such as changing one’s views about humanity in a more optimistic way.

Cova and Deonna (2014) consider awe as a distinct type of emotion of being moved by the experience of something related to one’s global beliefs ore core values. Schneider (2004, 2009) refers to awe as a moment of awareness and appreciation of the wonder and mysteries of life.

According to Haidt & Keltner (2004), we experience awe when we encounter a situation that is uncommonly vast in time, scope, complexity, and ability, in contrast with the known and familiar. Peak experiences (Maslow, 1964) and the experience of timelessness in flow (Csikszentmihalyi & Hunter, 2003) often involve the emotion of awe. Watching sunsets, listening to classic music, or worshipping God in a church or temple can all contribute to the emotion of awe.

Dobson (2015) provides a thorough review of the literature of awe and concluded that awe is related to a diminished sense of the self. For example, Shiota, Keltner, & Mossman (2007) found that research participants who were instructed to write about a time when they had encountered a beautiful natural setting were more likely than participants who were instructed to write about a time when they felt pride were more likely to report feelings of awe, and agree with the statements: “I felt small or insignificant” and “I felt the presence of something greater than myself” (p. 954). Shiota and colleagues suggested that the function of awe may be to re-oriented attention away from daily concerns and toward the complex or novel environment.

In a qualitative study, Bonner and Friedman (2011) also identified similar themes in their analysis of participants’ accounts of experiencing awe. Specifically, they found that when participants experienced awe, they described that they were part of something larger than themselves. In addition, the experience of awe was associated with decreased attention to the self. Generally, the emotion of awe contributes to a shift in focus and well-being (Rudd, Vohs, & Aaker, 2012) and ST goals (Seaton & Beaumont, 2015). Furthermore, Kristján Kristjánsson (2015) has also examined how awe is related to humility and virtue.

In view of this finer differentiation of four defining characteristics, I have revised the Self-Transcendence Measure initially presented in Wong (2016). The current revised version consists of items pertaining to each dimension, as shown in Appendix A.

CONCLUSION

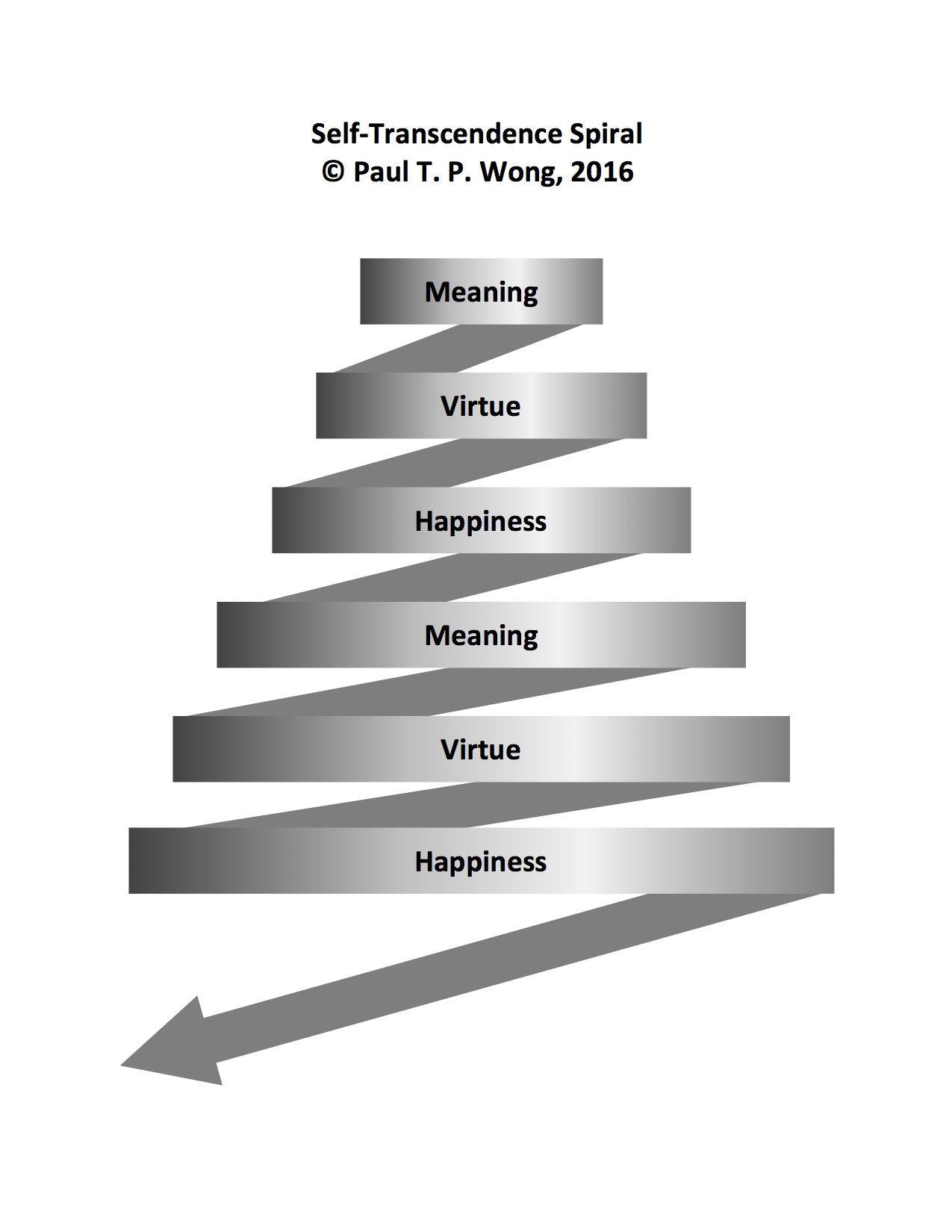

Together, these four characteristics produce the ST spiral, consisting of meaning-virtue-happiness cycles, which has a way of reinforcing each dimension of ST in each cycle of experiencing ST. Thus, the pursuit of ST has a way of contributing to spiritual growth.

The ever-expanding cycles of the ST spiral will grow to incorporate greater love for more people and greater loss of the self as the center of the world. Paradoxically, the expanding of the ST spiral and the loss of self liberates us from three human burdens so that we could fulfill all our potentials in order to give our best to the world. The first burden is the insatiable greed for more and more of the material world, which can never satisfy our spiritual needs for meaning and connection. The second burden is the nagging sense of meaninglessness because of the endless struggle and the fragility and brevity of life. The third burden is the unbearable boredom of the repetition of everything, no matter how stimulating it was at the beginning. The process of habituation inevitably sets in and, along with it, feelings of boredom.

Figure 2. Self-transcendence spiral.

The ST spiral offers relief and liberation from these burdens by virtue of the endless possibilities of discovering new meaning, new insights, and new ways to grow, serve, and connect. In short, ST frees us from the smallness and hollowness of a self-centered life for a full and vital life of expansion. The best part of ST is that when our opportunities in the material world dwindles because of our decline in physical health, our spiritual world can expand in terms of our love for others and for God or a Higher Power. Through the ST spiral, we can meet our deepest spiritual needs for meaning and relationships. Thus, the ST spiral is able to weave a beautiful life with three coloured threads—meaning, virtue, and happiness—in a seamless way.

The current research on ST represents part of my meaning hypothesis for the good life, consisting of meaning, virtue, and eudaimonic happiness (Wong, 2014b). The important role of meaning in achieving such a life has also been eloquently described by Steger (2012):

Meaning, by its very nature, appears to be an integrating factor in people’s lives, drawing together the threads of their efforts to achieve happiness, withstand distress, and attain transcendence beyond their solitary selves (Steger, 2009). (p. 165)

References

- Augustine. (2009). Confessions (H. Chadwick, Trans.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Batthyany, A. & Russo-Netzer, P. (2014). Meaning in positive and existential psychology. New York, NY: Springer.

- Bonner, E. T., & Friedman, H. L. (2011). A conceptual clarification of the experience of awe: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Humanistic Psychologist, 39(3), 222-235. doi:10.1080/08873267

- Braaten, A., & Huta, V. (2016). How fundamental worldviews about life and the world relate to eudaimonia, hedonia, and the experience of meaning. Paper presented at the 9th Biennial International Meaning Conference, Toronto, ON.

- Bridges, R. S. (Ed.). (1916). The spirit of man: An anthology. New York, NY: Longmans Green.

- Cova, F., & Deonna, J. A. (2014). Being moved. Philosophical Studies, 169(3), 447-466. doi:10.1007/s11098-013-0192-9

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Hunter, J. (2003). Happiness in everyday life: The uses of experience sampling. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4(2), 185-199. doi:10.1023/A:1024409732742

- Dobson, J. A. (2015). Examining the psychological consequences of experiencing awe [Unpublished PhD dissertation]. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

- Emmons, R. A. (2005). Striving for the sacred: Personal goals, life meaning, and religion. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 731–745. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00429.x

- Frankena, W. K. (1973). Ethics (2nd ed.). London, UK: Pearson.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Haidt, J. (2000). The positive emotion of elevation. Prevention & Treatment, 3(1). doi:10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.33c

- Haidt, J. (2003). Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 275-289). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Haidt, J., Algoe, S., Meijer, Z., Tam, A., & Chandler, E. C. (2000). The elevation-altruism hypothesis: Evidence for a new prosocial emotion. Unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

- Haidt, J., & Keltner, D. (2004). Appreciation of beauty and excellence: Awe, wonder, elevation. In C. Peterson & M. E. P. Seligman (Eds.), Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (pp. 537-551). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Kellert, S. R. (2012). Building for life: Designing and understanding the human-nature connection. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2009). Detecting and constructing meaning in life events. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), 317-330. doi:10.1080/17439760902992316

- Krause, N. (2007). Longitudinal study of social support and meaning in life. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 456-469. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.456

- Kristjánsson, K. (2015, December). Awe: An Aristotelian analysis of a non-Aristotelian emotion virtue. Presented at the Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Meeting in Columbia, South Carolina.

- Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak experiences. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

- McCormick, M. (n.d.). Immanel Kant: Metaphysics. Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/kantmeta/

- Rudd, M., Vohs, K. D., & Aaker, J. (2012). Awe expands people’s perception of time, alters decision making, and enhances well-being. Psychological Science, 23(1), 1130-1136. doi:10.1177/0956797612438731

- Schneider, K. J. (2004). Rediscovery of awe: Splendor, mystery, and the fluid center of life. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House.

- Schneider, K. J. (2009). Awakening to awe: Personal stories of profound transformation. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Psychology, 25(1), 1-65. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the content and structure of values? Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 19-45. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x

- Seaton, C. L., & Beaumont, S. L. (2015). Pursuing the good life: A short-term follow-up study of the role of positive/negative emotions and ego-resilience in personal goal striving and eudaimonic well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 39(5), 813-826. doi:10.1007/s11031-015-9493-y

- Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2006). Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with Big Five personality and attachment style. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 61-71. doi: 10.1080/17439760500510833

- Solomon, R. C. (1976). The passions: Emotions and the meaning of life. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

- Steger, M. F. (2012). Experiencing meaning in life: Optimal functioning at the nexus of well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.; pp. 165-184). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Tolstoy, L. (1921). A confession (A. Maude, Trans.). London, UK: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1882)

- Vasalou, S. (2015). Wonder: A grammar. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014a). The positive psychology of grit: The defiant power of the human spirit [Review of the film Unbroken]. PsycCRITIQUES, 60(25). doi:10.1037/a0039390

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014b). From attunement to a meaning-centred good life: Book review of Daniel Haybron’s Happiness: A very short introduction. International Journal of Wellbeing, 4(2), 100-105. doi:10.5502/ijw.v4i2.5

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016, June). Self-transcendence as the path to virtue, happiness and meaning Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

Appendix A: Self-Transcendence Measure-Revised

© P. T. P. Wong, I. Ivtzan, T. Lomas, O. Kjell, & E. Peacock, 2017

See first version, Self-Transcendence Measure (Wong, Ivtzan, Lomas, & Kjell, 2016)

See third version, Self-Transcendence Measure-Brief (Wong, Ivtzan, Lomas, Kjell, & Peacock, 2017)

Please respond to the following statements by circling the most appropriate response to the scale, from 0 (not at all characteristic of me or my beliefs) to 4 (a great deal characteristic of me or my beliefs).

| 1. | I enjoy the process of striving towards excellence in what matters. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 2. | A worthy lifelong pursuit ought to have some intrinsic value—something that is good in its own right. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 3. | My life is meaningful because I live for something greater than myself. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 4. | I focus on discovering the potential meaning in every situation. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 5. | I never intentionally harm others in striving to achieve my goals. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 6. | I devote my life to pursuing the ideals of beauty, goodness, and truth. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 7. | I find satisfaction in helping others, without expecting anything in return. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 8. | I feel that, at a deeper level, I am connected with all other human beings. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 9. | My suffering is more bearable when I believe that it is for my family, friends, and/or for a higher purpose. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 10. | Caring for my loved ones makes life worth living. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 11. | Paradoxically, one often experiences ecstasy and joy from “losing oneself” in moments of wonder and awe. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 12. | What matters most to me in life is the contribution I make to society. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 13. | It is categorically wrong to harm or kill innocent people in order to advance one’s own agenda. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 14. | In every situation, I am responsible to do what is right rather than what is convenient. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 15. | I have experienced deep satisfaction from serving a higher purpose or the common good. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 16. | I am amazed and inspired by extraordinary human achievements. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 17. | I sometimes feel a temporary loss of self when I am immersed in a wonderful experience. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 18. | At my funeral, I want to be remembered as a decent human being who cared about others. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 19. | I would rather be known as a good human being than a successful person. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 20. | I am often moved by the majesty and beauty of nature. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 21. | I make sure that whatever I do is consistent with my conscience and ethical/legal standards. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 22. | To live a meaningful life, one needs to value something or someone more than oneself. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 23. | I develop my full potential in order to give my best to benefit society. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

| 24. | I am more motivated by doing something meaningful than by the prospect of receiving external rewards. | 0 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 |

Scoring Key

- From Self-Centeredness to Serving Something/one Greater than Self: 3, 9, 10, 12, 22, 23

- From Extrinsic to Intrinsic Motivation: 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 24

- Guided by a Moral Compass: 5, 13, 14, 18, 19, 21

- Moved by Feelings of Awe and Deep Satisfaction: 8, 11, 15, 16, 17, 20

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2016, December). From Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy to the four defining characteristics of self-transcendence. Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, Columbia, SC. (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation).

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.