We are now living through an unprecedented time. COVID-19, the worst pandemic in modern history, has fundamentally changed life as we know it. Everyone’s life is disrupted. The virus is more contagious and deadly than anyone had expected. There seems no end to how bad things can become. In times of mortal danger, existential anxiety looms larger than our common worries. It takes nothing less than a resilience revolution to defeat the pandemic. In this special issue, I want to share with my readers a bold vision for positive change, and a few helpful road signs for moving forward with courage and hope.

A great deal of helpful information has been provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other academic resources on social distancing, self-isolation, and anxiety reduction (e.g., Goodyear & Falendar, 2020). However, what is missing from all these guidelines is the resilience factor—how we can become stronger as a result of the existential crisis that confronts all of us.

Growth in the aftermath of trauma and suffering has been much elaborated in psychology literature (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995; Tedeschi, Park, & Calhoun, 1998; Wong & Wong, 2012). The existential crisis of COVID-19 might save humanity from their mindless pursuits of pleasure and save the environment from more pollution by challenging us to reflect on how we should live and how we can become better and stronger people.

Existential positive psychology (PP 2.0) emphasizes human agency and the need for resilience to overcome obstacles and live a meaningful life (Frankl, 1985; Robbins & Friedman, 2011). From this positive perspective, the existential crisis may trigger the search for meaning. The preventive measure of self-isolation may provide much needed time to discover your true self—perhaps, even to follow your deepest yearnings to become what you were meant to be. In other words, instead of shrinking your life, you may actually expand and enrich your life through meaning, making COVID-19 a life-changing crisis (Frankl, 1985).

The Positive Transformation of the Hero’s Journey

Another way to understand this positive transformation is the hero’s journey according to Jung (1946/1983) and Campbell (1949/2008). The sudden disruption of life in an unexpected way can be viewed as part of the uncertainty and perils inherent in the human condition. The descent into the abyss actually sets the stage for the subsequent ascent and return to the upper world, with the hero regenerated and transformed. Campbell described a hero’s journey as:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man. (p. 23)

Different from mainstream psychology, which favors the reductionist cognitive-behavioural aspect, the humanistic-existential tradition is more holistic and inclusive of the spiritual, mythological account of the best aspects of humanity, commonly referred to as the soul. For example, James Hillman and colleagues (1979) emphasized that the soul naturally holds the potential for fulling our unique callings, much as an acorn is destined to become an oak tree.

Similarly, Cottinghan (2020) is explicit about soul as the spiritual aspect of personality and as the root cause of the human quest for meaning:

To say we have a soul is partly to say that we humans, despite all our flaws, are fundamentally oriented towards the good. We yearn to rise above the waste and futility that can so easily drag us down and, in the transformative human experiences and practices we call ‘spiritual’, we glimpse something of transcendent value and importance that draws us forward. In responding to this call, we aim to realise our true selves, the selves we were meant to be. This is what the search for the soul amounts to; and it is here, if there is a meaning to human life, that such meaning must be sought.

Frankl (1985) pointed out that this primary need for meaning has been buried by more earthly concerns and distractions, but our spirit or soul may be awakened by suffering. From this rich literature that celebrates the triumphant human spirit and from my own meaning research and practice (Wong, 2012a), there is sufficient reason to suggest that paradoxically, COVID-19 may be good for humanity in the long run.

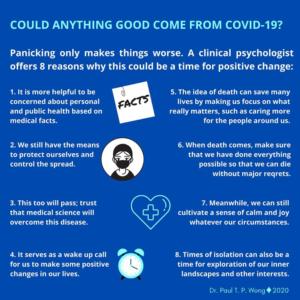

As a clinical psychologist, I can readily suggest a few practical tips on how to cope with COVID-19 in a transformative manner, as shown in Figure 1. This paper introduces Viktor Frankl’s concept of tragic optimism as the framework for resilience and positive transformation. Yes, you can do much better than just protecting your life from the virus; you can rise above it and become better and stronger, if you can apply Frankl’s wisdom to your own life.

Figure 1. Could Anything Good Come from COVID-19?

Viktor Frankl’s Concept of Tragic Optimism

Frankl (1985) describes his concept of tragic optimism in the following way:

I speak of tragic optimism, that is, an optimism in the face of tragedy and in view of the human potential which at its best always allows for: (1) turning suffering into a human achievement and accomplishment; (2) deriving from guilt the opportunity to change oneself for the better; and (3) deriving from life’s transitoriness an incentive to take responsible action. (p. 162)

In the above quote, he assured us that suffering could be good for you if you had the right understanding and the right attitude. I want to briefly discuss the three main points that could empower you to transform your trials and tribulations into a hero’s journey, as described earlier.

After Hong Kong went through the SARS crisis in 2003, I was invited by the hospital authority of Hong Kong in 2004 to speak on spiritual and compassionate care (Wong, 2004). My keynote was based on Viktor Frankl’s (1985) tragic optimism. It was gratifying that this address turned out to be very impactful because I was invited back several times to speak to all the major hospitals and universities in Hong Kong. Thus, it is only natural for me to return to same topic on coping with the present COVID-19 crisis, but with deeper understanding.

Frankl survived Nazi death camps and proved that tragic optimism worked even in situations much worse than what we have now. I, too, have both experienced and demonstrated the power of unrelenting optimism (Wong, 2007; Wong, 2019).

Here are the three principles of tragic optimism:

First, Accept the Present Suffering as an Opportunity for Heroic Achievement

Yes, even if you feel that you have not yet accomplished anything important in life, COVID-19 provides a rare opportunity to bring out your inner hero. Yes, even when you feel that you are in the deepest hell, you can still survive and thrive, but only if you can find some meaning in your suffering. Whether it is for your family, your mission, or your need to overcome, this simple re-orientation from self-concern to something worth suffering for will direct you from the abyss to the hilltop of heroism (Wong, 2012).

When you find your life totally disrupted, consider it as death to all that is wrong and an opportunity for rebirth and transformation. As Viktor Frankl describes in his book Man’s Search for Meaning (1985), you can choose to become your best by making some changes in your life and live as if you are living a second time. You are no longer satisfied with going about your daily business without thinking about the deeper meaning of life.

You may begin to reflect on your recurrent dreams and yearnings; you may begin to search for some value greater than yourself, such as caring for your family and serving your “neighbours.” Once your soul or healthy inner core is awakened, it will not be silenced:

There is something within us that is always reaching forward, that refuses to rest content with the utilitarian routines of our daily existence, and yearns for something not yet achieved that will bring healing and completion. (Cottinghan, 2020)

Suffering is no long painful once seen as a willing sacrifice out of love and service (Frankl, 1985). Furthermore, meaning needs to include sacrifice in the service of the common good, which also brings us an immense sense of satisfaction and gratitude, which could not be experienced in material things or physical pleasures.

Throughout the history of coping with epidemics, the Christian church has a history of sacrificial care for the people. For example, in 1527:

When the bubonic plague hit Wittenberg, Martin Luther refused calls to flee the city and protect himself. Rather, he stayed and ministered to the sick. The refusal to flee cost his daughter Elizabeth her life…it is better that we should die serving our neighbor than surrounded in a pile of masks we never got a chance to use. (Stone, 2020)

This hero’s quest for meaning is a double blessing. On the one hand, you are on an upward trajectory, as we strive towards a higher ground. On the other hand, you also feel good from helping your neighbors. In a way, you will be in a no-lose situation on the hero’s quest. Even if you live a sacrificial life and fail to achieve any earthly success, you can still have the satisfaction of living a meaningful life (Wong, 2012).

Properly understood, the meaning quest is a spiritual journey to discover and satisfy the deepest yearning of your soul. Therefore, you can experience inner peace and mature happiness (Wong & Bowers, 2018) in the midst of difficulties and suffering as you pursue meaning and self-transcendence (Wong, 2014; 2016). Here is another way to describe this transformed life:

The good life is not one that is achieved through momentary pleasures or defensive illusions, but through meeting suffering head on and transforming it into opportunities for meaning, wisdom, and growth, with the ultimate objective being the development of the person into a fully-functioning, mature being. (Emmons, 2003, p. 156)

Second, Channel Your Negative Emotions into the Motivation for Positive Change

COVID-19 deals us a double whammy: Not only does it deprive us of many usual sources of happiness and create a hole in our lives, but it also fills this hole with all kinds of fears and worries. Negative emotions can be just as contagious as the virus.

Are you sick and tired of feeling hopeless and helpless? Are you troubled by shame and guilt for wasted time and past mistakes? Are you tired of trying to stay optimistic in the midst of doom and gloom? Frankl suggests that you can channel these negative emotions into determination for positive change.

The first principle spells out how the search for meaning and the creative work of serving the common good can transform the decent to hell into a hero’s triumph. The second principle spells out how you can harness the negative motivation to make your life better by appreciating whatever life offers and learn to improve yourself in whatever way you can.

Instead of worrying about all the things beyond your control, why not enjoy all the small delights that life freely offers? Why not be grateful for the fresh air you breathe? Why not be filled with awe and joy as you savor the glorious sunset or look up at the starry sky? Why not immerse yourself with beautiful music?

Instead of wasting your time fretting in restless boredom, why not make optimal use of your time to improve yourself? The internet offers resources for you to learn mindful meditation, yoga, and all kinds of exercises to improve your health; it also offers resources to increase your knowledge, skills, and inner resources. Maybe now is the time for you to pursue what you have always dreamed of.

Instead of complaining about isolation and loneliness, why not spend time renewing relationships with your friends and spending more quality time with your family (e.g., over Skype)? One clear benefit of a prolonged lockdown or self-isolation is that we begin to appreciate the truth that other people matter, as Chris Peterson used to emphasize (Park, Oates, & Schwarzer, 2013). More importantly, the age of COVID-19 teaches us that we are part of the ecology (Lewis, 2012).

Be grateful for the opportunity provided by COVID-19. Don’t procrastinate. Today is the time for you to start making baby steps to become your best self. Solitude can open up new vistas of life. Whether you go for a walk in the park, read a spiritual book, or listen to music, you may rediscover the joy that you seldom experience during the usual hectic pace of life.

Third, Recognize that Being Aware of Life’s Finiteness Makes You Take Responsibility for Your Life

Yalom (2008) used to say that the idea of death can save many lives. A key concept of existential psychology is that death anxiety can fuel our motivation to take responsible action to live and die well.

As a free agent, you can either choose to remain a miserable victim, or to choose to aim high and make the world a better place for you and others.

Neither the government nor any other person can make that decision; only you and you alone can decide what to do with your life, especially at a critical junction of your journey. Life is short and fragile, but as long as you can breathe, you have the capacity to implement the first two principles of tragic optimism to make life better.

Many of life’s problems can also attribute to the failure to accept responsibility at both the personal level and government level. Peck (1978/2012) had this to say in his bestselling book The Road Less Travelled:

Most people who come to see a psychiatrist are suffering from what is called either a neurosis or a character disorder. Put most simply, these two conditions are disorders of responsibility…. The reason for this is that the problem of distinguishing what we are and what we are not responsible for in this life is one of the greatest problems of human existence.

COVID-19 has helped people, who used to be divided on political, religious, or racial grounds, come together. We are now facing a common enemy, which may devour all of us unless we are united in combating this invisible monster, which could be lurking anywhere. In a well-connected global village, we are all our neighbor’s keepers, and one person’s unhealthy behavior can adversely affect countless others.

That is why the responsible use of freedom is essential for survival and wellbeing at both the individual and societal level. The rising global death toll and the deepening economic crisis may make us feel like we are living in an apocalypse. But hopefully, it may also mean the end of our ignorance, complacency, and pride and the beginning of a new era of humble soul-searching and accepting responsibilities to make the world a better place for all.

Conclusion

From a positive perspective, the worst of times can also be the best of times. COVID-19 may indeed be a time of grace for us to change our attitudes and behaviors for the greater good: “People need to have a sense of urgent optimism. The future can inspire wonder, awe, and hope” (Gorbis, 2016). The disintegration of the old ways of life, coupled with the challenge of facing an uncertain and gloomy future, should provide the needed impetus to create new values and rise from the ashes like a phoenix. The above three principles of Frankl’s tragic optimism can equip us with the true grit and wisdom to reaffirm inherent human dignity and value and pursue the ideal of living a meaningful and resilient life.

To summarize the above, here is my song of life in the face of death:

Don’t waste your time waiting for a break;

Value your present and live fully right NOW;

There are always exciting things to do;

Whatever your present condition;

Be grateful for whatever you have;

Appreciate life as it is;

Improve yourself,

Build relationships,

Knock on doors,

Take the risk to seize the moment;

Move forward no matter how many times you’ve failed;

Keeping moving forward, even if you have to crawl;

Believe in your vision and don’t lose sight of your goal;

Pray for strength no matter how weak you feel;

That is how you can create a better future;

That is how you live a meaningful life with no regret;

Sing with me and let’s celebrate life together!

References

- Campbell, J. (1949/2008) The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Cottinghan, J. (2020). What is the soul if not a better version of ourselves? Aeon. Retrieved from https://aeon.co/ideas/what-is-the-soul-if-not-a-better-version-of-ourselves?fbclid=IwAR1nxJL1VLgsfH0a_dTqMGGG41CytQRFjMx1ZOVbLz7S5J20p2cKb0K1cZA

- Emmons, R. A. (2003). Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 105–128). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. New York: Washington Square Press.

- Goodyear, R., & Falendar, C. (2020). Resources for mental health practice during the current pandemic. University of Redlands. Retrieved from https://www.redlands.edu/study/schools-and-centers/cape/telehealth/

- Gorbis, M. (2016). The Future as a way of life: Alvin Toffler’s unfinished business. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@mgorbis/the-future-as-a-way-of-life-4bc314ec97de

- Hillman, J., Ritsema, R., Guggenbuhl-Craig, A., Kugler, P., & Rasula, J. (1979). Spring 1979 (An Annual of Archetypal Psychology and Jungian Thought). Washington, DC: Spring Publishing.

- Jung, C. G. (1946/1983). The Psychology of the Transference. New York: Bollingen Foundation Inc.

- Lewis, R. E. (2012). Ecohumanism: Integrating humanism and resilience theory. In M. B. Scholl, A. S. McGowan, & J. T. Hansen (Eds.), Humanistic perspectives on contemporary counseling issues (p. 191–214). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Park, N., Oates, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2013). Obituaries: Christopher Peterson “Other People Matter”: 1950–2012. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 5 (1), 1–4. doi:10.1111/aphw.12007

- Peck, M. S. (1978/2012). The Road Less Travelled. London: Rider.

- Robbins, B. D., & Friedman, H. (2011). Resiliency as a virtue: Contributions from humanistic and positive psychology. In M. J. Celinski & K. M. Gow (Eds.), Psychology of emotions, motivations and actions. Continuity versus creative response to challenge: The primacy of resilience and resourcefulness in life and therapy (p. 93–104). Nova Science Publishers

- Stone, L. (2020). Christianity Has Been Handling Epidemics for 2000 Years. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/13/christianity-epidemics-2000-years-should-i-still-go-to-church-coronavirus/?fbclid=IwAR0ZKQYgMXNIEe7XCHTLUsBmoy2YWLBykyq–s6lhl47qlFJJZmwLu0ieig

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1995). Trauma & transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Tedeschi, R. G., Park, C. L., & Calhoun, L. G. (Eds.). (1998). The LEA series in personality and clinical psychology. Posttraumatic growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2004). Compassionate and spiritual care: A vision of positive holistic medicine. International Network on Personal Meaning. Retrieved from http://www.meaning.ca/archives/archive/pdfs/wong-spiritual-care.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2007). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Anthology of Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen Inc.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). The meaning mindset: Measurement and implications. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 4(1), 1–3.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012a). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). Viktor Frankl’s meaning seeking model and positive psychology. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in existential and positive psychology (pp. 149–184). New York: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178/141

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Why and How I Developed the Positive Psychology of Suffering. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/why-and-how-i-developed-the-positive-psychology-of-suffering/

- Wong, P. T. P., & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (2012). A meaning-centered approach to building youth resilience. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 585–617). New York: Routledge.

- Yalom, I. D. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. The Humanistic Psychologist, 36(3-4), 283-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873260802350006\

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2020). Coping with the Mental Health Crisis of COVID-19: A Resilience Perspective. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/coping-with-the-mental-health-crisis-of-covid-19-a-resilience-perspective/?et_fb=1&PageSpeed=off

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.