A Historical Overview

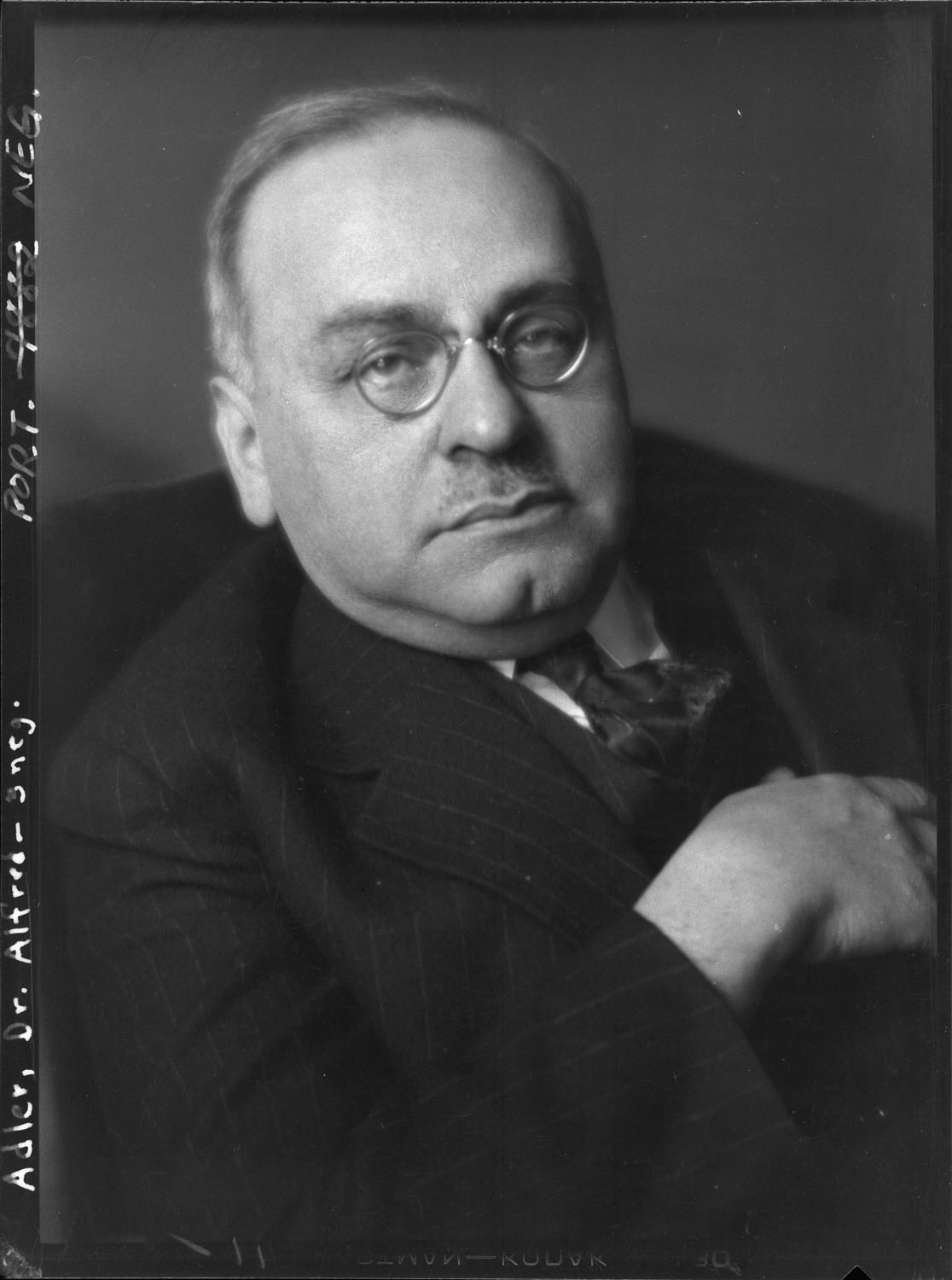

After leaving Freud’s Society of Psychoanalysis as a young, 18-year-old medical student, Frankl joined Adler’s Society for Individual Psychology from 1923 to 1927. During these four years, he was influenced by Adler, but was especially attracted to the anthropological wing led by Rudolf Allers and Oswald Schwarz within Adler’s circle. This faction was critical of Adler’s attempt to attribute mental disturbances almost exclusively to the lack of social interests. This group also felt that Adler failed to recognize the anthropological epistemology values towards community and one’s own innate conscience. In 1927, shortly after Allers and Schwarz announced their withdrawal from the Society for Individual Psychology, Frankl was also expelled from the Society because of his “unorthodox views” (Costello, 2014). According to O’Connell (1972), Frankl complemented Adler’s emphasis on courage and social interests, but also criticised the limitations of Adler’s individual psychology. Therefore, he justified his own work as the “Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy” because of his contribution to the meaning of suffering. In this paper, I will examine the similarities and differences between these two iconic giants in psychotherapy.

Differences in Emphasis and Orientation

Both schools are holistic, but Adler focuses on the social self, whereas Frankl focuses on the uniqueness of the spiritual/existential self. Adler favours a psycho-social approach and sees the self as a socially-embedded entity, a part of the whole. Thus, his approach to psychotherapy focuses on making sense of life and making contributions through interpersonal relationships. Adler seeks to awaken people’s social concerns and encourages cooperation, social equality, and democracy. In contrast, Frankl favours an existential-spiritual approach. He is more interested in how individuals relate to the existential givens, and how they find meaning through self-reflection and self-transcendence. Frankl’s approach to psychotherapy emphasizes Socratic dialogues and the courage to confront one’s existential concerns to discover meaning in all of life’s situations, beyond the relational realm. He seeks to awaken people’s awareness of their needs for meaning and personal responsibility to fulfill these spiritual needs.

Similar Concepts but Different Terms

Both Adler and Frankl emphasize self-transcendence. Adler frames it in terms of making a useful contribution to others and society. Such contributions represent the vertical meaning dimension. Although Adler recognizes the importance of how one relates to nature, he does not stress the spiritual nature of personhood. For Frankl, self-transcendence means something beyond oneself, something greater and more important (Frankl, 1985; Wong, 2014). This something can be others, a worthy cause, God, or nature. The pursuit of self-transcendence represents the vertical meaning dimension, which consists of both spiritual and relational components. Both share a common ground regarding the importance of courage. Adler has a more comprehensive account of courage throughout one’s lifespan in all three life tasks (work, love, and social relations), but courage is always through social interests and making useful contributions to others. To Adler,

the will to power is a process of creative energy or a psychological force desiring to exact one’s will in overwhelming life problems. It leads us to either normal self-enhancement in the interest of others, or a safeguarding tendency endlessly striving for perfection. This goal of self-ideal is also understood as superiority. (Yang, Milliren, & Blagen, 2010, p. 12)

For Frankl, courage is described as “the defiant power of the human spirit.” Courage is an emotional, volitional, and spiritual strength that empowers us to take a defiant stand for what is right and to pursue a worthy goal consistent with our core values and ethical responsibility despite dangers, adversities, and external pressures to surrender. Courage is especially associated with the attitudinal value as a way to wrest meaning out of a desperate situation, such as imprisonment in a Nazi death camp.

Different Approaches to Meaning in Life

Both Adler and Frankl emphasize meaning in life, but they differ in the scope they include and in their conceptualizations. Adler limits his discussion of meaning in life to the demands of three life tasks: work, love, and society, focusing on their relational aspects. In contrast, Frankl’s life tasks include work, love, suffering, and life/death issues, thus, following a broader, more existential orientation. For Adler, meaning comes primarily from social interests, which include a sense of belonging, feeling wanted, and striving for superiority through making a significant contribution to others. An individual’s social interest is key to his or her success in solving the problems of life and experiencing mean through relationships (Adler, 2009). His treatment of meaning covers the courage to address various relational issues, such as feelings of superiority and inferiority, the importance of cooperation, work, friendship, love, marriage, and progeny (Adler, 1931/2010). For Frankl, meaning is more than creative values through relational means. Meaning is based on creative, experiential, and attitudinal values. For Frankl, meaning stems from a spiritual rather than relational source; it stems from the spiritual needs of our hidden logos to follow our conscience and seek self-transcendence. For Frankl, meaning comes from the creative value (making a unique contribution), the experiential value (receiving good things in life), and the attitudinal value (taking a defiant stand towards adversity, with or without social support). As long as one is conscious, he has the responsibility to realize at least one of these values. Frankl also emphasizes the uniqueness of each individual as the basis for meaning. According to him, “we have seen how the meaningfulness of human existence is based upon the uniqueness and singularity of the human person… Love is living the experience of another person in all his uniqueness and singularity” (Frankl, 1986, p. 132).

Different Contributions

Adler’s main contributions are in education, social activism, and democracy. “According to Adler, social interest is salvation to human community, just as the gift of grace is to the faith community… Adler was concerned about the interconnectedness of the brotherly love and the commonwealth, the man-earth relationships” (Yang et al., 2010, p. 221). Frankl’s main contribution is to restore human dignity and spirituality to psychotherapy and individual lives, emphasizing individuals’ spiritual quests and struggles with sufferings. We find courage when we feel at home, when we do not consider merely the acceptable parts of life as belonging to us, but also the unacceptable things—when we accept the difficulties in our culture as a task at which we must work to improve the situation for all. According to Adler (1931) meaning is primarily achieved through contributions to others: “Those who have contributed are immortal, they have been in the stream of history, they have accomplished something for mankind, probably without giving it much thought.” I am grateful to those whose ideas and writing have contributed to my development, but I am also realistic, in that my success has been primarily due to my courage and faith in spite of all those who actively seek to marginalize or destroy me because they see me as a threat to their empire.

My Own Experience with Frankl and Adler

I have worked with ideas from both Frankl and Adler, but I have found Frankl’s ideas more resonant with my experiences. For example, Adler sees courage as a social function and essential for participating in relationships and community activities. Frankl prefers to see courage as coming from our spiritual or noetic core. Courage is evident when people dare to stand alone for their convictions to blaze a new trail. I have been a lone ranger, fighting by myself and feeling like a lone voice in the wilderness. My courage to be true to myself did not come from others, but from my conviction that I am on the right path and from my faith that God is my help and strength. Two beliefs keep me going, even when I am very tired: (1) I must complete my mission to make life better for millions of suffering people; and (2) God will give me the needed strength and complete his purpose in me. The first point of social interest is related to Adler and Buddhist teaching; the second of having God as a resource comes from Frankl and my Christian belief. From my experience in running Meaningful Living Meetups (Wong, 2016) and Neighbours Together Community meetings (for which I received the VanCity Cultural Harmony Award), I have found that it is harder to foster community interest than to awaken people’s interest in meaning. People are so pre-occupied with material gains and self-interests, it is hard to shift their attention from self to others. Most people have had bad experiences with people. There is so much cut-throat competition and back-stabbing at the workplace and so much conflict in our families that it is difficult to trust other people and place others’ interests above our own. Also, in a highly competitive and polarized world, it is difficult to treat others as our equals and care for them as brothers and sisters. For many people, those who do not agree with their values or views are denigrated as inferior or even evil, and are, thus, undeserving of respect and acceptance. Much needs to be done to introduce Adler and Frankl to the present generation. Together, their ideas can transform individuals and society and lead to a better future for all.

References

- Adler, A. (1931). The meaning of life. Adler Institute. Retrieved from http://www.adlerian.us/tp-7b.htm

- Adler, A. (2009). Social interest: Adler’s key to the meaning of life (Reprint ed.). C. Brett (Ed.). London, UK: Oneworld.

- Adler, A. (2010). What life should mean to you. Eastford, CT: Martino Fine Books. (Original published 1931)

- Costello, S. J. (2014, February 17). 1923-1927: From individual psychology to logotherapy (Frankl, Viktor) – Prof Alexander Batthyany. Dr. Stephen Costello. Retrieved from https://drstephenjcostello.wordpress.com/2014/02/17/1923-1927-from-individual-psychology-to-logotherapy-frankl-viktor-dr-stephen-costello/

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning (Revised & updated ed.). New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy (Revised & expanded ed.). New York, NY: Random House.

- O’Connell, W. E. (1972). Frankl, Adler, and spirituality. Journal of Religion and Health, 11(2), 134-138. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/27505115?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). Viktor Frankl’s meaning seeking model and positive psychology. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in existential and positive psychology (pp. 149-184). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Meaning centered positive group intervention. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 423-445). New York, NY: Springer.

- Yang, J., Milliren, A., & Blagen, M. (2010). The psychology of courage: An Adlerian manual of healthy social living. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2017, October 14). Ader versus Frankl: Similarities and differences. Invited talk presented at the Taiwan Society of Adlerian Psychology at the National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.