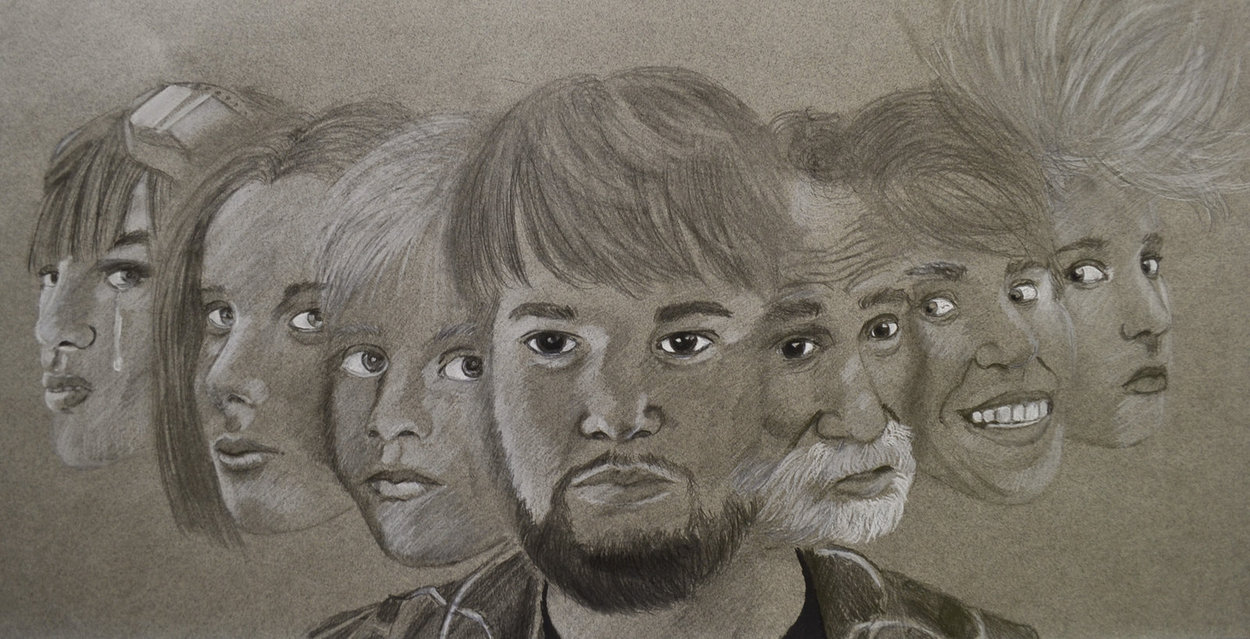

This case study focuses on one of my clients, who was a young man with disheveled long hair and unkempt clothing. His presenting problem was dissociative disorder with hypochondriac symptoms, such as pseudo-seizures after travelling by air or having a bad dream. He frequently did online searches for the meaning of his health concerns, even though his family doctor had reassured him that he was a healthy young man. He also mentioned that he was afraid of catching a cold and showed me the many layers of clothing he wore even indoors.

He had gone though several childhood traumas, although he denied that he had any. He was sent to live with his grandma when he was three, because of his parents had to move to a big city to work. He came to Canada as a 12-year child with his father 15 years ago, while his mother stayed in China working for the Chinese government. His father was always anxious and in poor health. His mother had recently joined them in Canada. He was their only child.

Shortly after migrating to Canada, his problem began when his father groped his groin area when he was sleeping. But he could not remember the details, except the repeated up and down movement of a closed hand with pounding sounds. He was scared and confused after this episode, and he attempted suicide to escape from the psychological pain.

Currently, he really wanted the pain in his groin area to go away, which had caused him erectile dysfunction problems, thus making it difficult for him to find a girlfriend and get married. He believed that when this problem is cured, all his other physical symptoms, such as pseudo-seizures and strange involuntary voices would vanish too. He never used the word sexual abuse, although I suspected that this trauma, which he tried to cover up, might been the source of many of his problems. He also complained that he had some issue with his tooth, which affected his speech. This issue also hindered his speaking at job interviews, thus, preventing from getting a job. But he did not see the need to see a dentist, because he did not have any toothache.

One phrase he frequently used was “Not really, but…” in response to any of my questions and suggestions. He denied that he ever had any nightmares, that he had been abused by his parents, that he was overthinking like his father, that he was worried about not having a girlfriend or a steady job; only to contradict himself a few minutes later. When I pointed out that these phrases were indicative of his denial as a defense mechanism, automatically he said, “Not really, but…” At this point, I confronted him that all people used defense mechanisms. He finally realized that he was indeed using this defence mechanism as his general life orientation.

Then, I explained to him that all of us are influenced by our unconscious mind. As a part of the integrative-meaning therapy, I explained to him how the unconscious mind worked and how clients’ defense mechanisms and resistance were part of the process of psychotherapy. If he really wanted help, he needed to trust me and cooperate to find solutions to his problems.

He then gave accounts of several incidents where he visited a place with his parents and said that he had been there before. But each time he told his parents, they insisted that it was just a dream. “But the voice that I heard and what I saw in my dreams are true”, he said emphatically. He had problems telling the difference between reality and dreams, between facts and myths. In addition to his amnesia of possible sexual abuse, and his frequent attempts to check himself for any sign of illness, he displayed classic symptoms of dissociative disorder with hypochondria and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). He had gone through several childhood traumas, such as being abandoned by his parents at three years old and molested by his father when he was 12. He also had a difficult history in school and at work. This was a complicated case that required long-term treatment. An hour had gone by, but I could not just let him go, being in no better shape than when he first came in. With his agreement, we agreed to extend another 50 minutes.

The turning point came when I told him that I was from the same city in China and spoke his dialect. At that point, he smiled and became more open to me. The second turning point came when I pretended to be one his parents, and said in Chinese with a very tender voice, “My precious baby 心肝宝贝, my only child, I will not allow any one to touch your hair.” He smiled and looked at me, saying, “That is exactly what my mother said to me. She often talked to me like this. But my father’s voice is always very stern.”

Having established a good rapport, we agreed to first look at more recent events that caused him a lot of stress and anxiety before we explore past traumas. He spoke about recent anxieties in this way: “Right now, I am afraid of getting hurt and I want to protect myself. The problem is, when I want to do something, such as asking a girl out, I may get hurt. If I don’t do anything, I still get hurt from being lonely or not getting anywhere. Either way, I cannot protect myself.”

In response, I applauded his existential insight, and explained that what he had just described was a universal existential dilemma – to do or not to do, to be or not to be, to remain the same or to change. No matter which way we choose, we will also face some uncertain or unpleasant things from which we really do not have adequate self-protection, because of the inherent human limitations.

We then explored the role of courage in an uncertain and dangerous world. I explained that in some situations, confronting the evitable fear was better than trying to avoid it. In fact, the more we run away, the more we will be fearful. In contrast, research has shown that by confronting our most feared object, the terrifying tiger becomes a toothless tiger.

Then we explored the role of reason, competence and bravery in facing the future: “Reason is a more reliable source of truth and knowledge than dreams or unconsciousness.” At this point, he said: “But, when I am physically weak, my reasoning ability is gone. I can reason, but only when I feel strong.” I clarified by saying: “Your capacity to reason may be weaker when you are physically sick, but for young people, they don’t completely lose their ability to think when they are physically sick. Besides, you can get help from family and friends for support, when your mind is too tired to solve a problem.”

I emphasized the importance of reasoning, because it allowed us to be grounded in reality. My reason can assure me that I am standing on a firm ground, or I am sitting on this chair. I can feel it, and I can do a reality test. My reason can confirm that I exist in time and space.

The final area we explored was faith. I mentioned that in some circumstances, no one could help us. “In ancient China, people prayed to the Sky God for help. In various cultures, people had some belief in a higher power to protect them or deliver them from dangers that were beyond human control.”

At this point, his face brightened up and he said, “My cousin believes in Buddha, and she has helped me get out of a bad dream.” In response, I said, “Buddhists believe that life is suffering; they also believe that there is a way to be delivered from suffering. One needs to have courage to face suffering and have the courage to believe in a higher power, whether it is Buddha, or the Sky God, or Christ, to help us.”

“Yes, I must talk more to my cousin, so that she could help me to develop more spiritual faith to overcome my fears,” he replied.

He left my counselling room with some basic skills and hope without paying anything. I hope that he would come back for further help, even if he did not have the money for therapy.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2020, January 13). A Case Study of Dissociative Disorder in Meaning Therapy.