Abstract

To resolve the controversy regarding the adaptive benefits of reminiscence, the study was conducted to investigate what types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging. On the basis of prior research and content analysis, 6 types of reminiscence were identified: integrative, instrumental, transmissive, narrative, escapist, and obsessive. Successful aging was operationally defined as higher than average ratings in mental and physical health and adjustment as determined by an interviewer and a panel of gerontological professionals. Reminiscence data were gathered from 88 men and women judged to be aging successfully and 83 men and women judged to be aging unsuccessfully. All subjects were between 65 and 95 years of age, with approximately half living in the community and half in institutions. As predicted, successful agers showed significantly more integrative and instrumental reminiscence but less obsessive reminiscence than their unsuccessful counterparts. Community dwellers also showed more instrumental and integrative reminiscence than institutionalized seniors showed. Thus, only certain types of reminiscence are beneficial.

Note: Some of the data in this article were based on an honors thesis by Lisa M. Watt. A brief version of the article was presented at the 96th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association in Atlanta, Georgia, 1988.

The research was supported by a grant from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada: Population Aging, awarded to Paul T. P. Wong.

We gratefully acknowledge James Birren, Robert Butler, Peter Cole-man, Marc Kaminsky, and Morton Lieberman for their helpful comments on a draft of this article. We also thank Anna May Young for her assistance in data analysis.

Reminiscence may be defined as personal memories of a distant past; it consists of long-term memories of events in which the reminiscer is either a participant or an observer (Ross, 1989). Since Butler’s (1963) seminal publication on the life review, interest in reminiscence has grown considerably in recent years (Birren, 1987; Birren & Hedlund, 1987; Coleman, 1986; Disch, 1988; Kaminsky, 1984; Wong, in press). The notion that reminiscence plays a major role in successful aging (Butler, 1974) has gained currency among researchers and professionals. An increasing number of seniors’ centers and nursing homes have included some sort of life-history discussion groups in their regular programs. Scores of reports on the values of reminiscence continue to appear regularly in the literature. For example, Goldstein (1987) reported that reminiscence can enhance well-being and reduce isolation in geriatric patients. Magee (1988) reported that poetic themes in life review enhance personal meaning and are especially helpful to intraverted and troubled seniors. Haight (1988) found structured life review to be therapeutic for the homebound elderly.

In the past two decades, a large number of studies have reported positive findings (e.g., Butler, 1971,1974; Cameron, Desai, Bahador, & Dremel, 1977-1978; Costa & Kastenbaum, 1967; Havighurst & Glasser, 1972; Lappe, 1987; C. N. Lewis, 1971,1973; Oliveria, 1982). Unfortunately, most of these reports are descriptive and anecdotal, and conflicting results have been reported (Merriam, 1980; Revere & Tobin, 1980-1981; Thornton & Brotchie, 1987). Other studies have found that reminiscence is of little or no aid in adapting to aging (Brennan & Steinberg, 1983-1984; Fallot, 1979-1980; Lowenthal, Thurnher, & Chiriboga, 1975; Perotta & Meacham, 1981-1982; Revere & Tobin, 1980-1981).

These discrepancies may be primarily due to the fact that most researchers in this area have treated reminiscence as a unitary phenomenon, without specifying the types of reminiscence involved (LoGerfo, 1980-1981; Molinari & Reichlin, 1984-1985; Romaniuk, 1981; Watt & Wong, 1990). Because different types of reminiscence may have different effects on well-being, a more fruitful approach may be to ask what types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging (Molinari & Reichlin, 1984-1985).

To address this fundamental question, a comprehensive taxonomy is needed. One approach is to classify individuals into different categories. For example, Coleman’s (1986) taxonomy focuses on attitudes toward reminiscence (i.e., positive, negative, avoidance, etc.) rather than on the actual contents of reminiscence. Similarly, Lieberman and Tobin (1983) devised a typology of life review in terms of individual styles (i.e., those who avoid life review, those who are currently involved in it, and those who have successfully completed life review).

Although useful for certain purposes, this individual-differences approach has certain drawbacks. The most serious problem is that to pigeonhole an individual into a certain category overlooks the fact that his or her recollections of the past may embody different types of reminiscence. Even those who have a positive attitude toward reminiscence may have some unpleasant memories, and those who are averse to reminiscence may find solace in pleasant memories from time to time. The absence of separate measures of different types of reminiscence for each individual makes it impossible to investigate how each type is related to well-being measures. Therefore, a typology based on content analysis of recollections is needed to determine which types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging.

Molinari and Reichlin (1984-1985) have reviewed several typologies of reminiscence. For example, McMahon and Rhudick (1964) identified three types of reminiscence, namely storytelling, life review, and defensive reminiscence. LoGerfo (1980-1981) also proposed three types of reminiscence: informative, evaluative, and obsessive, which parallel McMahon and Rhudick’s typology. However, Molinari and Reichlin pointed out that studies in the pertinent literature have not used any of the typologies because clear and reliable criteria to classify different types of reminiscence have never been provided.

Thus, there is a need to develop a comprehensive taxonomy and specify the rules to reliably classify reminiscence. The purpose of this article is to determine the validity of such a taxonomy and demonstrate that only the hypothesized adaptive types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging.

On the basis of past research and content analysis of the reminiscence data we have collected from hundreds of seniors, we have identified six types of reminiscence, namely integrative, instrumental, transmissive, narrative, escapist, and obsessive. This taxonomy incorporates all the major types of reminiscence in the literature and can accommodate all the available reminiscence data. More important, the defining characteristics for each type can be specified clearly to permit reliable content analysis.

A Taxonomy of Reminiscence

The main function of integrative reminiscence is to achieve a sense of self-worth, coherence, and reconciliation with regard to one’s past. It is similar to Butler’s (1963) life-review theory of reminiscence. He proposed that the elderly review their past in preparation for death. It is important to keep in mind that life review does not always succeed in achieving integration (Lieberman & Falk, 1971; McMahon & Rhudick, 1964). It may, in fact, involve feelings of guilt, failure, and depression (Butler, 1963; Coleman, 1986; McMahon & Rhudick, 1964). However, to the extent that one is able to achieve integrity, life review should contribute to successful aging in terms of increased self-understanding, personal meaning, self-esteem, and life satisfaction (Birren, 1987; Coleman, 1974, 1986; M. I. Lewis & Butler, 1974). The defining characteristics of integrative reminiscence are statements that indicate accepting one’s past as worthwhile (Butler, 1963), reconciling the discrepancy between ideal and reality (Birren, 1964), and accepting negative life events and resolving past conflicts (Lieberman & Tobin, 1983).

Instrumental reminiscence contributes to subjective perception of competence and continuity (Lieberman & Tobin, 1983). The defining characteristics include recollections of past plans, goal-directed activities and the attainment of goals, past attempts to overcome difficulties, and drawing from past experience to solve present problems. This type of reminiscence implicates the use of problem-focused coping strategies, which have been shown to be an important buffer against emotional distress (Billings & Moos, 1981; Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen, & DeLongis, 1986; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). It also reflects a sense of internal control that has been shown to be related to life satisfaction and subjective good health (Rodin, Timko, & Harris, 1985; Schulz, 1976; Slivinske & Fitch, 1987). Thus, it is predicted that instrumental reminiscence is also related to successful aging.

Transmissive reminiscence is indicated by references to the culture and practices of a bygone era, traditional values and wisdom, and the lessons learned through one’s past. McMahon and Rhudick (1964) observed that storytelling reminiscence had a positive effect on adaptation because it provided a valuable social function in terms of oral history and enhanced self-esteem. Simmons (1946) reported that moral instruction was often included in storytelling. Inasmuch as storytelling serves the function of passing on cultural ideals and personal wisdom, it should be more appropriately referred to as transmissive reminiscence.

Escapist reminiscence is characterized by a tendency to glorify the past and deprecate the present. It is also referred to as defensive reminiscence (LoGerfo, 1980-1981). Characteristic statements are those that boast of past achievements, exaggerate past enjoyments (with or without favorable comparisons with the present), or reveal a desire to return to the “good old days.” Butler (1963) suggested that although escapist reminiscence is generally not constructive, it can help maintain a steady state of psychological functioning. Lieberman and Tobin (1983) pointed out that the elderly may create a mythical past, portraying themselves as heroes, and that such mythmaking may help protect one’s self-esteem in the face of loss and decline.

Empirical studies have yielded some evidence in support of the benefits of escapist reminiscence (C. N. Lewis, 1971; McMahon & Rhudick, 1964). However, preoccupation with the past may also render the individual less effective in dealing with present demands and reduce present life satisfaction (Butler, 1963). Like any form of fantasy, escapist reminiscence may provide instant relief from a painful present, but it becomes unadaptive when it is prolonged and excessive to the point of engulfing one’s waking hours. Therefore, the relationship between this type of reminiscence and successful aging is more complex and cannot be determined without recording reminiscence over a protracted period.

Obsessive reminiscence originates from guilt over one’s past (LoGerfo, 1980-1981). It is indicative of one’s failure to integrate problematic past experiences, resulting in ruminations on these disturbing past events. Obsessive reminiscence is evidenced by statements of guilt, bitterness, and despair over one’s past. Butler (1963) observed that obsessive reminiscing could lead to depression, agitation, panic states, and even suicide. Coleman (1986) also documented the negative effects of obsessive reminiscence.

Narrative reminiscence is primarily a descriptive rather than an interpretive recollection of the past. The two main functions of this type of reminiscence are (a) to provide routine biographical information, such as date and place of birth, and (b) to recount past anecdotes that may be of interest to the listener. It is similar to informative reminiscence (LoGerfo, 1980-1981) and it is characterized by statements of autobiographical facts, simple accounts of past events without interpretation or evaluation, and statements that do not belong to the integrative, instrumental, transmissive, escapist, or obsessive categories. In other words, simple narrative can also be defined by excluding other types of reminiscence.

The adaptive function of narrative reminiscence remains unclear. On the one hand, a long narrative reminiscence may reflect good retention of the details of past events, indicating good cognitive functioning. On the other hand, it may reflect verbosity, which is a sign of decline in intellectual functioning (Gold, Andres, Arbuckle, & Schwartzman, 1988). Therefore, we do not have any theoretical or empirical basis to predict the relationship between narrative reminiscence and successful aging.

The first objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that integrative, instrumental, and transmissive types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging, whereas obsessive reminiscence is associated with unsuccessful aging. A differential-population research strategy was used to directly contrast the reminiscence data of successful and unsuccessful seniors.

A second objective of this study was to identify the effect of living conditions on reminiscence. In their review of the literature, Molinari and Reichlin (1984-1985) pointed out that whereas most studies using community-dwelling samples have found a positive relationship between reminiscing and adaptation, research using institutionalized subjects or a mix of community and institution dwellers has found either a negative relationship between the two variables or no relationship at all. Admittedly, community-dwelling seniors and institutionalized seniors differ in many dimensions, such as in health and age; however, some research suggests that institutionalization may have an impact on reminiscence (Butler, 1963; Pincus, 1970; Tobin & Etigson, 1968). Therefore, we also compared successful with unsuccessful elderly living in institutions.

Method

Subjects

Four hundred subjects (65 years and older) took part in the screening interviews of the Ontario Successful Aging Project, which was designed to provide an intensive, longitudinal study of various psychosocial factors that contribute to resilience and vitality in old age. These include reminiscence, living environments, social resources, control beliefs, stress, and coping.

Two hundred of these subjects were recruited from the community through various means, such as poster notices, radio and newspaper advertising, contacts with community agencies, and “snowball” sampling. The other 200 were recruited from nine retirement homes and three nursing homes. Because of institutional regulations, a different recruitment procedure had to be used. We first sought the approval from the administrator of each institution, then we obtained a list of residents considered suitable for participation by the nursing staff, and finally we contacted these individuals personally to solicit their participation.

A thorough screening procedure was used to identify successful agers. In Step 1, an experienced interviewer asked the respondent a series of nine questions at the respondent’s residence. These questions were designed to measure the respondent’s general attitudes toward life. Here are some of the items: “Can you tell me a little bit about your present situation—how things are going with you at the moment?” “Do you think that you are coping well with many of life’s problems, such as health, finance, family? Can you give me an example of how you cope with some of these problems?” The interviewer then completed three Likert-type rating scales that measured physical well-being, mental well-being, and adjustment. These ratings were based on the interviewer’s general impression of the contents of the answers as well as on observations of the respondent’s tone of voice, posture, behavior, and general appearance. Furthermore, the ratings were always made in comparison with age peers under similar circumstances. The combined rating scores on all three scales provided an index of the wellness status of each respondent.

In Step 2, the respondent was interviewed by a panel of professionals, again at the respondent’s residence. This typically took place within 1 month after the initial interview. Each panelist asked several questions dealing with his or her area of expertise. A psychologist or psychiatrist focused on the respondent’s adaptation process. A geriatric nurse focused on the respondent’s past health history and present health condition. A gerontological recreational worker focused on the person’s daily activities and general interests. At the end of the interview, each panelist independently arrived at a rating score for each of the same three dimensions as the interviewer. Selection of successful and unsuccessful subjects was based on the total ratings from the interviewer and all three panelists.

Thus, an extremely costly and time-consuming screening procedure was used to ensure that the successful agers were indeed superior in mental and physical health and adjustment. Such a screening procedure has proved very effective in that significant differences between successful and unsuccessful agers were subsequently obtained over a wide array of measures of well-being and psychosocial factors.

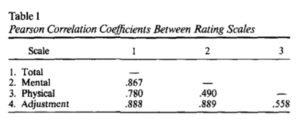

Pearson correlation coefficients between the three dimensions and the total rating scale are shown in Table 1. All correlations were significant beyond .001. It is clear that the three scales are highly related to the total rating scale. To assess the degree of agreement among the three panelists and the interviewer, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients among the four judges for each of the three dimensions and the total rating scale; they were .81 (mental), .86 (physical), .86 (adjustment), and .88 (total rating). This strong evidence of convergence justifies the combination of the total rating scores from the four judges to yield the total wellness index.

Pearson correlation coefficients between the three dimensions and the total rating scale are shown in Table 1. All correlations were significant beyond .001. It is clear that the three scales are highly related to the total rating scale. To assess the degree of agreement among the three panelists and the interviewer, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients among the four judges for each of the three dimensions and the total rating scale; they were .81 (mental), .86 (physical), .86 (adjustment), and .88 (total rating). This strong evidence of convergence justifies the combination of the total rating scores from the four judges to yield the total wellness index.

Subjects were then rank ordered according to the total wellness index. This was done separately for the 200 community-dwelling subjects and the 200 institutionalized subjects. For each sample, 50 elderly subjects were selected randomly from the top 40% (successful elderly) and 50 from the bottom 40% (unsuccessful elderly), yielding a total of 200 subjects chosen for a longitudinal study. For various reasons, such as sickness, death, failure to complete all the interviews, or refusal to participate, the total sample was reduced to 171 individuals. They were distributed in four groups as follows: successful community (n = 45), successful institution (n = 45), unsuccessful community (n = 45), and unsuccessful institution (n = 36). Note that the unsuccessful institution group had the highest nonparticipation rate.

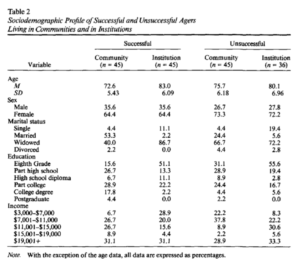

The sociodemographic variables of the four groups of subjects are shown in Table 2. Statistical analyses revealed that successful and un successful groups did not significantly differ in terms of marital status, x2(3, N = 171) = 5.63, p < .13; income, F(1, 164) = 0.064, p <.80; age, F(1, 164) = 0.007, p < .93; or sex, x2(1, N = 171) = 1.189, p < .17. However, the two groups differed in terms of education, F(1, 164) = 4.21, p < .04. The successful group (M = 2.71) attained a higher level of education than the unsuccessful group (M = 2.30). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) also revealed that community subjects were younger and better educated than their institutionalized counterparts, F(1, 164)= 64.03 and 14.63, respectively (ps < .001).

The sociodemographic variables of the four groups of subjects are shown in Table 2. Statistical analyses revealed that successful and un successful groups did not significantly differ in terms of marital status, x2(3, N = 171) = 5.63, p < .13; income, F(1, 164) = 0.064, p <.80; age, F(1, 164) = 0.007, p < .93; or sex, x2(1, N = 171) = 1.189, p < .17. However, the two groups differed in terms of education, F(1, 164) = 4.21, p < .04. The successful group (M = 2.71) attained a higher level of education than the unsuccessful group (M = 2.30). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) also revealed that community subjects were younger and better educated than their institutionalized counterparts, F(1, 164)= 64.03 and 14.63, respectively (ps < .001).

In comparison with the unsuccessful group, the successful group indeed had a significantly higher level of subjective well-being, F(1, 167) = 24.48, p < .001, according to Reker and Wong’s (1984) Perceived Well-Being Scale. The successful sample also had better physical health, F(1, 167) = 10.09, p < .001, as measured by a physical symptoms checklist adapted from the Older Americans Resources and Services strategy (Pfeiffer, 1976). We also found that community-dwelling subjects had higher subjective well-being F(1, 167) = 36.55, p < .001, and better physical health, F(1, 167) = 7.02, p < .01, than institutionalized subjects had.

Procedure

The reminiscence data were collected at the residence of the subject. The respondents were first asked to tell a little bit about their past and then were asked to “tell…something of your past that is most important to you—that is something that has had the most influence on your life.” If the respondent was not clear, then the request was rephrased. Generally, the respondents were not rushed in any way, but they were encouraged to review their past and to identify one or two events that had significantly shaped their lives. This critical-incident approach to studying reminiscence helps subjects focus on the landmarks or water-sheds in their past without guiding them to specific themes. We believe that more can be learned about the adaptive functions of reminiscence by having individuals remember significant events, such as major transitions or crises in the past, rather than the mundane details of everyday life.

Scoring

The entire reminiscence interview was audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were content analyzed and scored by one of the authors, who did not take part in the interviews. Because the subjects were identified by a code provided by the programmer, who alone knew their identity, the authors were blind with regard to the status (successful vs. unsuccessful) and domicile (community vs. institution) of the subjects.

In content analyzing a running text, the coding unit can be based on a word, a paragraph, or the whole text (Holsti, 1969; Weber, 1990). The advantage of coding each word is that coding can be reliably accomplished by computer software packages (Weber, 1990). Word frequency can be useful in providing a rough sketch of the landscape of one’s past (Schneidman, 1989) but can become tenuous when used to embody abstract ideas. For example, no single word can ever adequately represent the concept of integrative reminiscence.

The difficulty of achieving high reliability arises when coding the entire text because of the complexity of such a task. It is particularly troublesome for coding reminiscence. For example, a given passage of recollections may encompass several types of reminiscence. An individual may talk about past plans (i.e., the instrumental type) along with simple accounts of family background (i.e., the narrative). Therefore, this passage cannot reliably be coded as representing only one type.

Given the difficulties just mentioned, we chose the paragraph as the basic coding unit. The text can be readily divided into paragraphs according to the basic rules of English style. For example, each paragraph may have more than one complete sentence, but must contain only one self-contained idea. Therefore, each paragraph can be reliably classified into only one of the mutually exclusive categories.

Two simple rules were used to classify the paragraphs. First, each paragraph is coded in only one category. Second, to be coded as a particular reminiscence type, the paragraph must contain at least one of the defining characteristics of that type as previously described. The coding manual, together with practice materials, is available from the authors; however, the following examples are presented here to illustrate the coding procedure.

When I was a teenager, my parents broke up and both remarried. I was very resentful because they did not seem to care about my feelings or needs. But as I grow older and look back, I understand that they were really not compatible with each other. They had suffered for many years before their divorce. Now, I’m on good terms with both sets of parents.

Because the quoted paragraph conveys the idea of resolving past conflicts, it is coded integrative.

During the Great Depression, life was very hard. There were very few jobs, and money was difficult to come by. But we learned to survive by budgeting and making do without many things. The lessons I learned in those years have really helped me in trying to live on my old-age pension.

In this instance, the idea of drawing on past experiences to solve present problems is clear; therefore, it is coded instrumental.

My husband died when I was away for two days visiting my friends in the West. He fell in the bathtub and eventually died because there was no one there to help him. It has been years now, but I still cannot forgive myself for leaving him home alone for two days.

Because this passage reveals persistent feelings of guilt, it is clearly the obsessive type.

Occasionally, a respondent would digress and introduce topics other than reminiscence. At this point, the interviewer would remind the respondent to focus on recollections. Such digressions occurred very rarely and were excluded prior to the application of coding rules.

After coding was completed, all the paragraphs belonging to the same reminiscence type were grouped together, and the number of words in these paragraphs was taken as a measure of this type. The total number of words of the entire text, which may contain different types of reminiscence, represents the total reminiscence output by each subject.

Working with narrative data can never achieve the same level of precision and reliability as measuring more discrete functions, such as reaction time. However, the criteria are sufficiently clear to permit reliable classification. To check on the reliability of the coding procedure, two judges coded reminiscence data from 30 subjects. To take into account the different categories and guessing, kappa statistics were used, which revealed a significant interjudge reliability (K = .88, p < .001).

Results

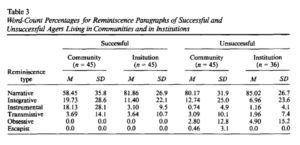

The distribution of types of reminiscence was expressed in percentages obtained by dividing the word count of each type summed over paragraphs by the total reminiscence output for each respondent. The mean percentage and standard deviation for each reminiscence type are shown in Table 3.

Because of the marked verbosity of some individuals and the positive skew of the distribution, the word-count scores were transformed to a log+1 scale (Tukey, 1977). The data were later subjected to a 2 (well-being status) X 2 (domicile) multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA; via SPSSX software) with reminiscence types as the dependent variables. The escapist type was excluded from the analysis because only 1 subject exhibited this type. The main effects of status, F(5, 163) = 6.86, p < .0001, and domicile, F(5, 163) = 2.32, p < .05, and the Status X Domicile interaction, F(5, 163) = 2.78, p < .05, were significant.

Because of the marked verbosity of some individuals and the positive skew of the distribution, the word-count scores were transformed to a log+1 scale (Tukey, 1977). The data were later subjected to a 2 (well-being status) X 2 (domicile) multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA; via SPSSX software) with reminiscence types as the dependent variables. The escapist type was excluded from the analysis because only 1 subject exhibited this type. The main effects of status, F(5, 163) = 6.86, p < .0001, and domicile, F(5, 163) = 2.32, p < .05, and the Status X Domicile interaction, F(5, 163) = 2.78, p < .05, were significant.

Univariate ANOVAs revealed a significant main effect of status for integrative, F(1, 167) = 6.90, p < .01; instrumental, F(1, 167 = 15.75, p < .001; and obsessive types of reminiscence, F(1, 167) = 8.32, p < .001. As predicted, successful subjects demonstrated more integrative and instrumental and less obsessive reminiscence than did unsuccessful subjects. The instrumental finding, however, was qualified by the interaction between domicile and status, F(1, 167) = 9.91, p < .01. This interaction reflects the fact that although successful elderly demonstrated more instrumental reminiscence than unsuccessful elderly did, the difference was greater for the community dwellers than for the institutionalized subjects. Successful subjects did not differ significantly from unsuccessful subjects in transmissive, F(1, 167) = 0.05, p < .82, or narrative reminiscence, F(1, 167)= 0.08, p < .78.

Significant main effects of domicile were found for integrative types, F(1, 167) = 4.47, p < .05, and instrumental types, F(1, 167) = 5.08, p < .05, but not for the other types of reminiscence. Community dwellers showed more integrative and instrumental reminiscence than did institution dwellers.

Because of a significant difference between successful and unsuccessful subjects in education, a multivariate analysis of covariance was performed with education as the covariate. The main effect of status was again significant, F(5, 163) = 5.25, p < .01. Univariate analyses yielded a significant main effect for integrative, F(1, 167)= 4.62, p < .05; escapist, F(1, 167) = 8.11, p < .01; and instrumental reminiscence, F(1, 167) = 42.99, p < .001. The domicile main effect of instrumental reminiscence was again significant, F(1, 167) = 5.04, p < .05. The Status X Domicile interaction was significant, F(5, 163) = 2.66, p < .05, mainly because of a significant interaction in instrumental reminiscence, F(1, 167) = 10.62, p < .001. We also tabulated the number of subjects in each group that exhibited one or more paragraphs of each reminiscence type (not shown here). Chi-square tests on the tabulation produced similar results. Thus, the adaptive benefit of integrative and instrumental reminiscence did not appear to be a statistical artifact.

The average total word count with all types of reminiscence combined was 424.13 words. An ANOVA of the total word-count data indicated that there was no significant difference in the overall amount of reminiscing: domicile, F(1, 167) = 1.31, p < .28; status, F(1, 167) = 2.927, p < .08; Domicile X Status interaction, F(1, 167) = 0.01, p < .97.

Discussion

By providing separate assessments of different types of reminiscence, we were able to show predictable differences between successful and unsuccessful elderly, even when the total amount of reminiscence did not differentiate between the two samples. This finding reinforces our contention that the adaptive function of reminiscence cannot be clarified without specifying and measuring the diverse types of reminiscence emitted by each subject.

Our finding regarding integrative reminiscence suggests that it is not the process of life review but the achievement of integrity in such a review that promotes successful aging. It corroborates Lieberman and Tobin’s (1983) finding that those who have achieved reconciliation in life review tend to show a higher level of life satisfaction. It also provides direct empirical support of Butler’s (1963) hypothesis regarding the adaptive function of life review.

The positive relationship between instrumental reminiscence and successful aging is consistent with the vast literature that links internal locus of control with well-being in the elderly (e.g., Wolk & Kurtz, 1975; Ziegler & Reid, 1983). It is also consistent with the literature on the adaptive benefits of problem-focused coping in the elderly population (e.g., Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, & Novacek, 1987). One can readily cite numerous adaptive advantages of this type of reminiscence. It not only provides past examples of successful solutions to present problems but may also enhance the elderly person’s sense of mastery.

The absence of any significant difference between successfully and unsuccessfully aging elderly in their use of transmissive reminiscence could be due to the fact that the interview setting is not an appropriate forum for transmitting personal wisdom or cultural heritage. The interviewer may be perceived as an expert or authority figure, and it is unlikely that the respondents would try to teach the interviewer a few lessons. The low prevalence of this type of reminiscence in this study is consistent with this explanation. Had we directly asked the subjects to share some of the wisdom they had acquired, the successful elderly might indeed have had more to offer.

The functional nature of narrative reminiscence remains unclear in the literature. On the one hand, a high level of narrative reminiscence may indicate verbosity and perseveration; on the other hand, it may reflect a retentive memory for a rich and varied past. A more fine-grained analysis is needed to clarify the role of narrative reminiscence. One possibility is to develop ways to measure the styles of narration in terms of verbosity, clarity, and other attributes.

We have clearly demonstrated that integrative and instrumental types of reminiscence are characteristic of successful aging. This is an important first step toward resolving the fundamental controversy regarding the adaptive benefits of reminiscence; however, this finding does not by itself prove a causal relationship. Nevertheless, it paves the way for experimental manipulations and hypothesis testing. For example, one can conduct reminiscence sessions that focus on the development of integrative and instrumental types to determine whether these manipulations will result in a higher level of well-being than would result from unguided reminiscence or a control group that only gathered together to discuss social issues.

The association between integrative and instrumental types of reminiscence and successive aging also needs to be subjected to theoretical and experimental analysis. One plausible interpretation is that personal memories are guided by the self-schemata one possesses in the present (Ross, 1989). Positive self-schemata, such as self as a competent achiever and self as a meaningful, worthy being, may have biased the successful agers toward instrumental and integrative types of reminiscence. In other words, these two types of reminiscence may be consequences rather than causal agents of successful aging. An alternative interpretation is that these types of reminiscence directly contribute to adaptation to the aging process by making avail-able useful coping resources from the past. One may also hypothesize that these adaptive benefits may be mediated through a self-concept that has been enhanced by instrumental and integrative reminiscence. Up until now, reminiscence research generally has been in a prescientific descriptive stage. Having developed an adequate and valid taxonomy, we can now proceed to design experimentally controlled studies to test these theoretical implications.

The differences in reminiscence scores between institutionalized and community dwellers parallel those between successful and unsuccessful elderly. Because community dwellers tend to have better health and enjoy more activities than institution dwellers, their recall may again be biased. It is also plausible that instrumental and integrative reminiscence have given these subjects an adaptive edge and enabled them to maintain independence in a community setting. The low level of instrumental reminiscence in institutionalized subjects may also be mediated partially by an environment that fosters dependence rather than autonomy (Barton, Baltes, & Orzech, 1980). A related interpretation is that the respondents in institutions tend to be in poorer health than the community dwellers; therefore, they have less desire for control and greater dependence on others for healthcare (Reid, 1984; Smith et al, 1988). The present taxonomy has made it possible to test these hypotheses in future research.

Finally, our typology has encouraging hypothesis validity (Weber, 1990). Different types of reminiscence indeed produced the results we expected with respect to successful aging. Thus, the adaptive types (integrative and instrumental) occurred more frequently for the successful elderly, whereas the unadaptive type (obsessive) occurred more frequently for the unsuccessful elderly.

In sum, this study has helped clarify the adaptive role of reminiscence and has opened up new avenues of research and therapy It is now possible to study the effects of different types of reminiscence on well-being and competence in a prospective design. Furthermore, the new taxonomy has broadened the scope of reminiscence therapy and suggested new ways of psychological intervention with the elderly (Watt & Wong, 1990; Wong, in press).

References

- Barton, E. M., Baltes, M. M., & Orzech, M. J. (1980). Etiology of dependence in older nursing home residents during morning care: The role of staff behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 423-431.

- Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1981). The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 139-157.

- Birren, J. E. (1964). The psychology of aging. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Birren, J. E. (1987, May). The best of all stories. Psychology Today, 21, 91-92.

- Birren, J. E., & Hedlund, B. (1987). Contributions of autobiography to developmental psychology. In N. Isenberg (Ed), Contemporary topics in developmental psychology (pp. 394-415). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Brennan, P. L., & Steinberg, L. D. (1983-1984). Is reminiscence adaptive? Relations among social activity level, reminiscence and morale. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 18, 99-109.

- Butler, R. N. (1963). The life review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry, 26, 65-76.

- Butler, R. N. (1971, December). Age: The life review. Psychology Today, 7, 49-51.

- Butler, R. N. (1974). Successful aging and the role of the life review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 22, 529-535.

- Butler, R. N. (1980-1981). The life review: An unrecognized bonanza. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 12, 35-38.

- Cameron, E, Desai, K. G, Bahador, D., & Dremel, G. (1977-1978). Temporality across the life-span. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 8, 229-259.

- Coleman. P. G. (1974). Measuring reminiscence characteristics from conversation as adaptive features of old age. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 5, 281-293.

- Coleman, P. G. (1986). Aging and reminiscence processes: Social and clinical implications. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Costa, P., & Kastenbaum, R. (1967). Some aspects of memories and ambitions in centenarians. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 110, 3-16.

- Disch, R. (1988). (Ed.). Twenty-five years of the life review. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 12 (3, Whole No. 4).

- Fallot, R. D. (1979-1980). The impact on mood of verbal reminiscing in later adulthood. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 10, 385-400.

- Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Gruen, R., & DeLongis, A. (1986). Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 571-579.

- Folkman, S, Lazarus, R. S., Pimley, S, & Novacek, J. (1987). Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology and Aging, 2, 171-184.

- Gold, D., Andres, D., Arbuckle, T, ASchwartzman, A. (1988). Measurement and correlates of verbosity in elderly people. Journal of Gerontology, 43, 27-33.

- Goldstein, M. (1987). Poetry: A tool to induce reminiscing and creativity with geriatrics. Journal of Social Psychiatry, 7, 117-121.

- Haight, B. K. (1988). The therapeutic role of a structured life review process in homebound elderly subjects. Journal of Gerontology, 43, 40-44.

- Havighurst, R. J., & Glasser, A. (1972). An exploratory study of reminiscence. Journal of Gerontology, 27, 245-253.

- Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Jung, C. G. (1933). Man in search of a soul. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Kaminsky, M. (1984). The uses of reminiscence: New ways of working with older adults. New York, NY: Haworth Press.

- Lappe, J. M. (1987). Reminiscing: The life review therapy. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 13,12-16.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Lewis, C. N. (1971). Reminiscing and self-concept in old age. Journal of Gerontology, 26, 240-243.

- Lewis, C. N. (1973). The adaptive value of reminiscing in old age. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 6, 117-121.

- Lewis, M. L, & Butler, R. N. (1974). Life-review therapy: Putting memories to work in individual and group psychotherapy. Geriatrics, 29, 165-173.

- Lieberman, M. A., & Falk, J. M. (1971). The remembered past as a source of data for research on the life cycle. Human Development, 14, 132-141.

- Lieberman, M. A., & Tobin, S. S. (1983). The experience of old age: Stress, coping and survival. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- LoGerfo, M. (1980-1981). Three ways of reminiscence in theory and practice. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 12, 39-48.

- Lowenthal, M. F., Thurnher, M., & Chiriboga, D. (1975). Four stages of life: A comparative study of men and women facing transitions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Magee, J. J. (1988). Using poetry as an aid to life review. Activities, Adaptation and Aging, 12, 91-101.

- McMahon, A. W, & Rhudick, T. J. (1964). Reminiscing: Significance in the aged. Archives of General Psychiatry, 10, 292-298.

- Merriam, S. (1980). The concept and function of reminiscence: A review of the research. The Gerontologist, 20, 604-609.

- Molinari, V, & Reichlin, R. E. (1984-1985). Life review reminiscence in the elderly: A review of the literature. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 20, 81-92.

- Oliveria, O. C. (1982). Understanding old people: Patterns of reminiscing in elderly people and their relationship to life satisfaction. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Tennessee.

- Perotta, P, & Meacham, J. A. (1981 -1982). Can a reminiscing intervention alter depression and self-esteem? International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 14, 23-29.

- Pfeiffer, E. (1976). Multidimensional functional assessment: The OARS methodology. Durham, NC: Duke University Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development.

- Pincus, A. (1970). Reminiscence in aging and its implication for social work practice. Social Work, 15, 47-53.

- Reid, D. W (1984). Participatory control and the chronic-illness adjustment process. In H. Lefcourt (Ed.), Research with the locus of control construct: Extensions and limitations (Vol. 3, pp. 361-389). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Reker, G. X, & Wong, P. T. F (1984). Psychological and physical well being in the elderly: The Perceived Well Being Scale (PWB). Canadian Journal on Aging, 3, 23-32.

- Revere, V, & Tobin, S. (1980-1981). Myth and reality: The older person’s relationship to his past. International Journal of Aging and Hu-man Development, 12,15-25.

- Rodin, J., Timko, C, & Harris, S. (1985). The construct of control: Biological and psychological correlates. In M. P. Lawton & G. L. Maddox (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (Vol. 5, pp. 3-55). New York, NY: Springer.

- Romaniuk, M. (1981). Review: Reminiscence and the second half of life. Experimental Aging Research, 7, 315-336.

- Ross, M. (1989). Relation of implicit theories to the construction of personal histories. Psychological Review, 96, 341-357.

- Schneidman, E. (1989). The Indian summer of life: A preliminary study of septuagenarians. American Psychologist, 44, 684-694.

- Schulz, R. (1976). Effects of control and predictability on the physical and psychological well-being of the institutionalized aged. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33, 563-573.

- Simmons, L. W (1946). Attitudes toward aging and the aged in primitive societies. Journal of Gerontology, 1, 72-95.

- Slivinske, L. R., & Fitch, V L. (1987). The effect of control enhancing interventions on the well-being of elderly individuals living in retirement communities. The Gerontologist, 27, 176-181.

- Smith, R. P., Woodward, N. J, Wallston, B. S., Wallston, K. A., Rye, P., & Zylstra, M. (1988). Health care implications of desire and expectancy of control in elderly adults. Journal of Gerontology, 43, 1-7.

- Thornton, S., & Brotchie, J. (1987). Reminiscence: A critical review of the empirical literature. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26, 93-111.

- Tobin, S. S., & Etigson, E. (1968). Effect of stress on earliest memory. Archives of General Psychiatry, 19, 435-444.

- Tukey, J. W (1977). Exploratory data analysis. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Watt, L. M., & Wong, P. T. P (1990). A taxonomy of reminiscence and therapeutic implications. Journal of GerontoIogical Social Work, 16, 37-57.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Wolk, S., & Kurtz, J. (1975). Positive adjustment and involvement during aging and expectancy for internal control. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 173-178.

- Wong, P T. P. (in press). Reminiscence: Therapy and research. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Ziegler, M, & Reid, D. W (1983). Correlates of change in desired control scores and in life satisfaction scores among elderly persons. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 16, 135-146.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., & Watt, L. (1991). What types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging? Psychology and Aging, 6(2), 272-279.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.