Abstract

This paper explains the need for existential positive psychology (PP 2.0) from three different angles. First, psychology needs to move towards integration in order to meet the mental health challenges during COVID-19. Second, PP 2.0 provides a promising approach to both address existential threats and advance global wellbeing. Third, a dialectical dual system strategy (Wong, 2012) for psychological research and interventions is introduced. Finally, a spiritual vision of global wellbeing through self-transcendence is presented.

Is it possible that we may have gotten it wrong when it comes to how to achieve happiness and wellbeing (Barnes, 2020; Thin et al., 2017)? Is it possible that the key to positive mental health is to learn how to endure and transcend suffering according to ancient Chinese wisdom (Deng et al., 2020; Wong; 2016a)? These questions suggest that we may need to seriously rethink about how to achieve global wellbeing and positive mental health in the era of COVID-19.

The history of psychology is marked by different waves with different schools dominating in different eras, such as behavioral psychology, humanistic psychology, and positive psychology. Waterman (2013) argued that because of philosophical differences, humanistic psychology and positive psychology should go their separate ways in advancing human potentials and wellbeing. However, most humanistic psychologists (Held, 2004; Mruk, 2008; Robbins, 2008; Schneider, 2010) are in favor of integration, with humanistic psychology as the dominant brand. In contrast, I propose that the future of psychology may belong to a balanced integration of existentialism and positive psychology according to the ancient wisdom of non-duality and self-transcendence.

At present, it is increasingly difficult to ignore the reality of suffering as humanity is under various existential threats: The pandemic, climate change, extremism, nuclear warfare, and the abuse of digital power. What kind of solution could psychology offer? Existential positive psychology (PP 2.0) seems to be the logical answer because it seeks evidence-based positive solutions to the existential crises facing individuals and humanity.

Life is basically tragic, especially in the era of COVID-19 (Wong, 2021). In addition to natural disasters, diseases, and social-economic stressors, much of human suffering is existential (Bates, 2016). Life is inherently tragic because we are born alone, struggle alone, and then die alone; often happiness is just an illusion to distract us from existential suffering. But deep inside, there is a still a nagging sense of loneliness and boredom because of all the broken connections within us, with others, and with something bigger than we are. From an existential perspective, we cannot be truly happy if we cannot adequately address the basic disunity and disharmony within us. Erich Fromm (1959) argues persuasively that this deep-seated existential need for inner harmony compels us to strive for unity and balance in all spheres of being, the kind of mature happiness advocated by Wong & Bowers (2018).

What is Existentialism?

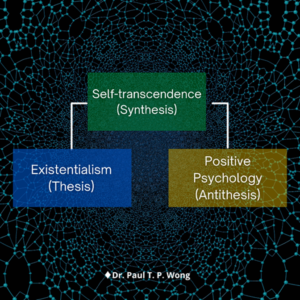

Broadly speaking, existentialism includes different types of existential philosophy and psychology (Van Deurzen et al., 2019). It is primarily concerned with understanding the human condition of frailty, suffering, and the human struggle for happiness (Wong, 2017a); this represents the thesis. Positive psychology includes both humanistic and positive psychology. It is primarily concerned with bringing out what is good in us and fulfilling human potential; this represents the antithesis. PP 2.0 is intended to integrate the best from both existentialism and positive psychology for the betterment of humanity – this is the synthesis (figure 1). I named this integrative approach PP 2.0 because it is fundamentally different from the positive psychology (PP) championed by Martin Seligman (Wong & Roy, 2018).

Figure 1

Existential Positive Psychology as the synthesis of Existential Psychology and Positive Psychology

Any psychological label or classification is at best a fussy category because of its imprecise nature. I am fully aware that the label existential positive psychology will not please either tribe, but it represents my best attempt to characterize my integrative approach. I also acknowledge that many researchers have already independently factored in an existential dimension of suffering in their research on wellbeing (e.g., Emmons, 2003; Fowers et al, 2017; Maddi, 2006; Schneider, 2004; Shmotkin, 2005) and although they may not agree to be identified with this new label, the nature of their research nevertheless still falls within the broad parameter of PP 2.0.

My Vision of Existential Positive Psychology

My editorial (Wong, 2004) for the first issue of International Journal of Existential Psychology & Psychotherapy was entitled “Existential Psychology for the 2lst Century”. At the beginning of this article, I already sketched my new vision for PP 2.0:

“What is existential psychology? By definition, it is the psychology of human existence in all its complexity and paradoxes. Human existence is more than an abstract concept; it involves real people in concrete situations. Unencumbered by its philosophical roots, existential psychology needs to become the practical psychology of everyday living – how to survive and thrive in the midst of tensions between good and evil, hope and despair, love and hate, courage and safety, agency and community. It is about the high dramas of coping, dreaming, and transformation. It is the mature, positive psychology of how to live and die well in spite of the conflicts and tensions that pervade human existence. Shifting through the colliding narratives and contradicting ‘facts’, existential psychology seeks to address fundamental questions relevant to the survival of humanity and the well-being of every individual.” (p. 1)

Those research questions included:

- What does it mean to exist and live as a human being….What are our deepest yearnings and most cherished dreams? What are the highest riches of human aspirations?

- What does it mean to be authentic and fully alive? How can we discover our true identity? …How do we maintain a passion for living, when things are not going well? How can we function fully, develop our full potentials, and remain optimistic in an oppressive or hostile environment?

- What are the givens of human existence? What is the structure of human existence in all its complexity and duality? What is the meaning of suffering, pain and death? What is the meaning of life in light of these negative givens? …How can we integrate both the negative and positive givens to facilitate personal growth and community development?

- What are the forces that shape the human condition? What are the social and psychological underpinnings of the horror of war and atrocity? How can we change the conditions that perpetuate human misery and injustice?

The bolded sentences highlight the important research questions for the new science of flourishing through suffering, which has consumed all my time and energy during the past 20 years. At the time of writing this editorial, it was very clear to me that any hope of answering these challenging questions demanded a holistic methodology, as articulated in my conclusion for that editorial:

“In order to create a body of knowledge regarding all aspects of human existence, the journal will value the subjective, phenomenological experiences of the person, as well as the objective, observable and measurable behaviours. It does not see any contradiction between the holistic study of the whole person and the quantitative, experimental research of certain psychological attributes; both approaches can enrich our understanding of human existence. Life is full of paradoxes, puzzles and mysteries. Therefore, I would like to see creative, innovative methods to illuminate the seemingly incomprehensive, inexplicable wonders and horrors of human existence.” (p. 2)

Now, fast forward to the beginning of 2021. Over the years, my vision has remained the same (Wong, 2009, 2016b) but it has evolved in so many positive ways that it justifies a change of the journal’s name to International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology—the only peer-reviewed journal entirely devoted to the integration of existential psychology and positive psychology. In this new editorial, I want to detail some of the changes in PP 2.0.

Reframing Positive Existential Psychology (Wong, 2004, 2009) as Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0; Wong, 2010, 2011)

There are many reasons for this subtle change of the journal title. First of all, I hope to attract more contributions from positive psychologists and have a greater impact on mainstream psychology. Elsewhere, I have articulated this need for PP 2.0 (Wong, 2015; Wong & Roy, 2018; also see Wikipedia, 2019).

Secondly, during the coronavirus pandemic, the message of how to survive and thrive through suffering seems more attuned to the emotional needs of people struggling with all the dangers, restrictions, and anxieties of pandemic fatigue. The cherry tune of happiness must be jarring to the ears of all those who are either grieving the death of a loved one due to COVID-19 or worrying about dying from it. Expressions like “body full of happiness” or “embodiment of happiness” simply remind people of their fragility and mortality.

Thirdly, it is impossible for human beings to flourish without addressing the inescapable reality of human suffering (Fowers et al., 2017; Van Deurzen, 2008; Wong, 2019a). We need to go beyond the pursuit of happiness and refocus on energy how to transcend pandemic fatigue and our vulnerabilities. According to Contestabile (2018), increased global mobility increases the risk of a pandemic, and technological and cultural changes pose new risks for suffering which “cannot be compensated by happiness across individuals.”

Finally, it is not possible for positive psychology to fully understand of the richness and complexity of human flourishing by depending only on the epistemology of positivism and the ideology of materialism and scientism (Wong & Roy, 2018). For example, when the deep and profound meaning of human existence with all its struggles and sufferings was reduced to a set of inadequate operational definitions simply because young researchers lack the deep understanding of life and the existential literature (Wong, 2016c), the resulting publications on meaning will not really contribute to our understanding of existential meaning as a lived phenomenological experience.

Exciting New Theoretical Developments in PP 2.0 And Their Heuristic Values For Research And Interventions

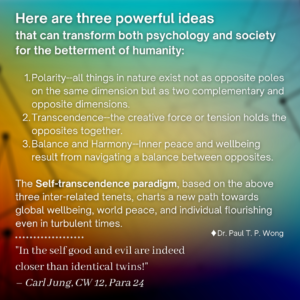

Here, I will just introduce a few theories which are potentially fruitful. At the heart of PP 2.0 is the need for understanding dialectical interactions between Yin-Yang to achieve a dynamic balance for wellbeing (Lomas, 2016;Wong, 2012). It is fundamental to study and understand how the bright and dark sides of human personality and situations interact to yield optimal wellbeing. Paradoxically, we need the dual-system approach (Wong, 2012) to achieve non-duality that good and evil are two sides of the same coin, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

A self-transcendence approach to achieve non-duality and wellbeing

The deep-and-wide hypothesis (Wong & Worth, 2017) about the creative problem-solving process is just part of the efforts to understand what is good and beneficial about negative emotions. If necessity is the mother of all invention, then the feelings of frustration and desperation are the driver of creativity. My deep-and-wide hypothesis complements Fredrickson’s (2001) broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions.

The development of a taxonomy of suffering is the foundation of a science of flourishing through suffering (Fowers et al., 2017; Wong, 2019b, 2020a). More refinement is needed for a comprehensive taxonomy of suffering and measurement of suffering (Anderson, 2014; Joye, 2011).

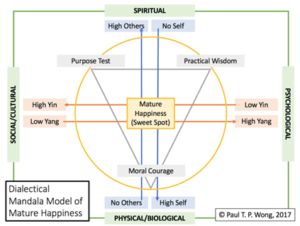

Figure 3

Dialectical Mandala Model of Mature Happiness

The development of a deep joy amidst suffering is also an important area of a new measure of sustainable happiness in spite of suffering (Wong & Bowers, 2018). This kind of mature happiness is based on learning how to achieve a dynamic balance between the positive and negative life force in each context. Accordingly, sustainable durable wellbeing can only be achieved when we are able to achieve an adaptive balance between our existential yearnings for love, meaning, and faith (the golden triangle), with the ancient dark emotions – guilt, shame, and fear (Mayer et al., in press; Wong, 2019a) or the tragic triad of guilt, suffering, and death (Frankl, 1946/1985). This involves self-transcendence over negative emotions to maintain inner peace and self-transcendence over egotistic interest to serve others. Mature happiness, a positive mental state of inner peace, harmony, and contentment, is based on a deep spiritual or philosophical understanding and the ability to manage a dynamic balance between opposite forces with wisdom, courage, and meaning/purpose, as shown in figure 3.

There are reasons to believe that this is a distinct third types of happiness, different from hedonic happiness and eudaimonia. Mature happiness can also be understood as deep happiness (Delle Fave et al., 2016) with its emphasis on harmony, or authentic-durable happiness (Dambrun et al., 2012) with its emphasis on contentment and inner peace.

There are reasons to believe that this is a distinct third types of happiness, different from hedonic happiness and eudaimonia. Mature happiness can also be understood as deep happiness (Delle Fave et al., 2016) with its emphasis on harmony, or authentic-durable happiness (Dambrun et al., 2012) with its emphasis on contentment and inner peace.

In fact, my concept of mature happiness is very similar to the Buddhist concept of happiness. According to Thich Nhat Hanh (2014), the secret to happiness is seeking peace, not excitement; to transform suffering, not run away from it. Furthermore, Ekman et al. (2005) defined happiness as:

“a state of flourishing that arises from mental balance and insight into the nature of reality. Rather than a fleeting emotion or mood aroused by sensory and conceptual stimuli, sukha is an enduring trait that arises from a state of mental balance. It entails a conceptually unstructured and unfiltered awareness of the true nature of reality.” (p. 60)

Dambrun et al. (2012) have developed an authentic-durable happiness based on contentment and inner peace. They have also found evidence that self-transcendence values are related to authentic-durable happiness and should make it more resistant to the impact of negative circumstances. In short, mature happiness is more sustainable or durable because it is based on the human capacity to achieve balance and self-transcendence.

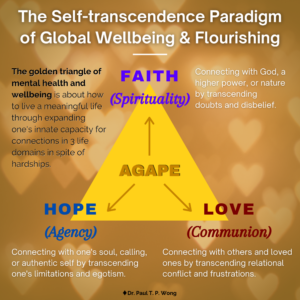

The self-transcendence paradigm of wellbeing and personal growth is probably the most important theoretical development. It is similar to The Connections Paradigm by Dr. David H. Rosmarin (2021) which involves the connection of opposites in three domains: inner connection, interpersonal connection, and spiritual connection. The main difference is that my paradigm focuses on realizing connections with the self, with others, and with God through the process of self-transcendence.

Simply put, self-transcendence involves a fundamental reorientation from an egotistic focus or selfishness, to selflessness and caring for others or something greater than oneself. This is essentially a paradoxical model of personal growth and self-actualization through self-transcendence and suffering (Wong, 2016d). The new science of self-transcendence as a uniquely human phenomenon is the central theme of PP 2.0 (Frankl, 1946/1985, 1966; Kaufman, 2020; Wong, 2016d, 2020a; Yaden et al., 2017).

I’m grateful for my long conversations with Dr. David Bakan while teaching at York University more than 30 years ago. He sought me out for dialogues because I was an experimental psychologist who happened to be a Christian. He was curious about my thoughts about his Jewish-Freudian integration (Bakan, 1958). These discussions with the author of Duality of Human Existence (Bakan, 1966) sowed the seed for my self-transcendence paradigm of holistic wellbeing. Bakan believed in the triad of human experience, which is agency, communion and spirituality:

- Agency = a sense of ego and divine calling, responsible for progress in science and prosperity and the feelings of isolation and absurdity.

- Communion = a need for connection with others and belonging to a community to mitigate the downsides of agency.

- Spirituality = God is the projection of our agency and communion and represents our human needs for redemption or cure of the human soul from sins (Gorday, 1998). Existential suffering results from sacrificing or surrendering an important part of one’s self for the “good of the whole” as demonstrated by Abraham’s sacrifice of his son for his tribe, Job’s sacrifice for his own integrity, and Jesus’ sacrifice for humanity. In all three areas, ego-detachment is necessary.

This may be an oversimplification of Bakan’s integration of Jewish mysticism and psychoanalysis (Bakan, 1958) and his attempt to relate religious faith with personality. However, it is enough for me to integrate Bakan with Frankl’s logotherapy (1946/1985; Wong, in press-a), resulting in the self-transcendence paradigm of PP 2.0.

Figure 4

The Golden Triangle

According to PP 2.0, the golden triangle of meaning, relationship and spirituality constitutes the three pillars of positive mental health. There is a vast literature supporting each of these three pillars. For meaning, see Wong (2012) and Hick & Routlege (2013). For relationship, see Ainsworth (1989) and Harvard Health Publishing (2017). For spirituality, see Koenig (2009) and Weber & Pargament (2014). At a deeper level, the three pillars of mental health refer to faith, hope and love (figure 4). These three values are so fundamental to global wellbeing because we are all parts of a larger whole; to be happy and mentally healthy, we need to be connected with others by love, connected with God or some higher power by faith, and connected with our true self and calling thorough self-compassion (Neff, 2015). To be whole is to transcend all the barriers and get reconnected in all three important spheres of life. When we cannot find enough compassion within ourselves to love ourselves or others, we need to resort to God’s agape love, the ultimate source of all actions of charity (Rosmarin, 2021).

According to this self-transcendence model, the root causes of mental illness and existential suffering lie in our brokenness in all three life domains. We are broken within ourselves—with our constant inner conflict and tumult in a divided self. Similarly, our relationships with family, friends, and the community are broken—torn by endless misunderstanding, conflicts, and power struggle. Our union with God is broken—we are separated and alienated from God by our unbelief, ignorance, pride, and sin.

Therefore, the cure for human suffering and the restoration of peace and happiness depends on the healing and transformation of brokenness to wholeness and oneness. Regarding the inner connections, the key to human happiness and mental health is learning how to maintain a dynamic balance between the heart’s desires and mind’s rational judgement, between the dark and bright side of personality. For example, my integrative meaning therapy (Wong 2010, 2016e, 2020b) focuses on the fundamental human needs for meaning, relationship, and spirituality, with the human quest for meaning (self-transcendence) as its central organizing construct, and harmony as its desirable outcome.

The New Frontiers of Empirical Studies And The New Research Agenda

The new theoretical developments (seen above) can generate a great deal of exciting research that can both expand and transform our understanding of human flourishing and wellbeing. There has been a lot of creative energy on the empirical front. In addition to the two special issues of Counselling Psychology Quarterly on Second Wave Positive Psychology (Wong, 2019c), and an upcoming special issue of Frontiers in Psychology on the new science of PP 2.0 (Wong et al., in press), there are numerous research studies related to PP 2.0 (e.g., Ivtzan, et al., 2015; Wong, 2019c).

With respect to the holistic research methodology for the integrative PP 2.0, I have already proposed some preliminary ideas of integrative humanistic-existential psychology research with positive psychology research (Wong, 2011, 2017b).

PP 2.0 embraces William James’ (1912) radical empiricism which “bridges the split between subjective and objective, qualitative and quantitative.” (Wong, 2011, p. 410). Moving beyond artificial confines of experimental research, “such radical empiricism would also examine all recorded human activities, from history, anthropology, literature, and religion to shed light on the human condition and the person.” (Wong, 2011, p. 411).

This holistic methodology also insists on the imperative of including a component of existential-phenomenological experience for all quantitative studies. This component is essential to check whether the view of the experimenter is consistent with the view of participants. This mixed methodology will prevent experimenters from coming to wrong interpretations of their quantitative data.

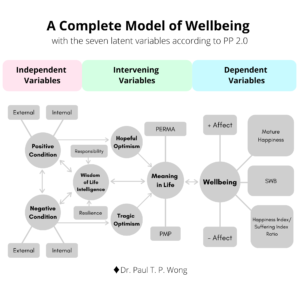

Here is my latest proposal of a dual-system approach to research on human flourishing through suffering (figure 5). Basically, my proposal involves a paradigm shift of including suffering or unpleasant condition as an independent covariable or statistic covariate. Results from such research will yield a more complete understanding of global wellbeing in the context of unavoidable human miseries, both subjective and objective (Anderson, 2014).

Figure 5

A complete model of wellbeing

- Normal life conditions are seldom normal because of (a) our inherent limitations and foibles, and (b) the inevitable suffering. That is why the old science of pursuing happiness does not work especially during a pandemic.

- The new science proposes that (a) the approach and avoidance systems must work together (Wong, 2012), (b) any setbacks during the pursuit of happiness will trigger the aversive system, and (c) in coping with the inevitable suffering, we are capable of transforming it to achievement and mature happiness.

- Thus, by embracing suffering, the approach system has a better chance of success and the avoidance system has a better chance of transforming suffering into success. Therefore, flourishing is more likely if we embrace suffering.

- We need to embrace the dark side of life as the other half of the complete circle of wellbeing. True positivity, whether happiness or character strength, can only be seen in the darkness.

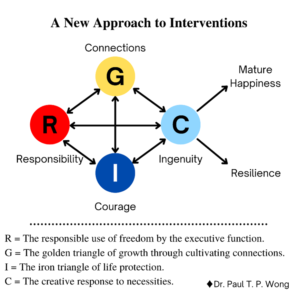

This new research paradigm is accompanied by a new self-transcendence approach to intervention as depicted in figure 6 and explained in Wong (2020a, 2020b, Wong in press-b). All four inter-related areas are needed to repair what is broken to bring out what is best in us. It is noteworthy this new approach focuses on balance and harmony as the key to happiness and wellbeing (Lomas, 2021; Wong & Bower, 2018).

Figure 6

A new approach to psychological intervention

The present editorial indicates that PP 2.0 may be the most exciting new development in both positive psychology and existential psychology because it changes the paradigm of wellbeing research in important ways which will deepen our understanding of healing and flourishing. There can be no large-scale human flourishing without the collective struggle to create a just and compassionate society. Power, whether monetary or military, is never the answer to human problem. Agape love or compassion is the answer to human miseries.

Paradoxically, instead of focusing on individual signature strengths, PP 2.0 focuses on our need for courage, humility, compassion, and connections (e.g., Rosmarin, 2021; Van Tongeren & Van Tongeren, 2020; Wong, 2020b) as the less travelled road to personal growth and flourishing (Wong, 2016d). Only then can we be liberated from the tyranny of egotism, negative emotions, and defence mechanisms; only then can we be free to pursue our highest aspiration to become what we are meant to be – decent and compassionate human beings.

We don’t dream of a utopia, because evil and suffering are part of human existence in this world. By faith, we can only dream of co-creating a better world where ordinary, imperfect people can learn to live in peace with themselves, with each other, and with nature without any kind of tyrannic control. We can all strive to co-create country where we can be free to worship, free to celebrate life together with family and friends, and free to struggle to find our authentic path so that we can do what we love and at the same time do what benefits others, no matter how hard life is. Such an objective is achievable. If more people learn how to replace egotism with self-transcendence (Wong, Mayer & Arslan, in press ) This is my spiritual vision of global wellbeing.

References

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709-716. Doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709

- Anderson, R. E. (Ed.). (2014). World suffering and quality of life. Springer.

- Bakan, D. (1958). Sigmund Freud and the Jewish mystical tradition. D Van Nostrand.

- Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence: An essay on psychology and religion. Rand Mcnally.

- Barnes, S. (2020). What we get wrong about happiness. According to a real happiness professor. HuffPost. https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/entry/what-we-get-wrong-happiness_l_5e2f0916c5b67d8874b72959?ncid=engmodushpmg00000003

- Bates, A. T. (2016). Addressing Existential Suffering. BCMJ, 58(5), 268-273. https://bcmj.org/articles/addressing-existential-suffering

- Contestabile, B. (2018). The Cultural Evolution of Suffering. Socrethics.com https://www.socrethics.com/Folder2/Culture.htm

- Dambrun, M., Ricard, M., Després, G., Drelon, E., Gibelin, E., Gibelin, M., Loubeyre, M., Py, D., Delpy, A., Garibbo, C., Bray, E., Lac, G., & Michaux, O. (2012). Measuring happiness: From fluctuating happiness to authentic–durable happiness. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, Article 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00016

- Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Wissing, M. P., Araujo, U., Solano, A. C., Freire, T., Hernández-Pozo, M. D. R., Jose, P., Martos, T., Nafstad, H. E., Nakamura, J., Singh, K. & Soosai-Nathan, L. (2016). Lay definitions of happiness across nations: The primacy of inner harmony and relational connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(3), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00030

- Deng, J., Li, T., Wang, J., & Zhang, R. (2020). Optimistically Accepting Suffering Boosts Happiness: Associations Between Buddhism Patience, Selflessness, and Subjective Authentic-Durable Happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 223-240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00083-0

- Deurzen, E. van. (2008). Psychotherapy and the Quest for Happiness. SAGE publications.

- Deurzen, E. van., Craig, E., Längle, A., Schneider, K. J., Tantam, D., & du Plock, S. (Eds.). (2019). The Wiley World Handbook of Existential Therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J., Ricard, M. & Wallace, B. A. (2005). Buddhist and Psychological Perspectives on Emotions and Well-Being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 59-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00335.x

- Emmons, R. A. (2003). The psychology of ultimate concern. The Guilford Press.

- Fowers, B. J., Richardson, F. C., & Slife, B. D. (2017). Frailty, suffering, and vice: Flourishing in the face of human limitations. American Psychological Association.

- Frankl, V. (1966). Self-transcendence as a human phenomenon. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 6, 97–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/

- Frankl, V. E. (1946/1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Fromm, E. (1959). Psychoanalysis and Religion. Yale University Press.

- Gorday, P. J. (1998). The Thought of David Bakan: Overview and Implications for Christology. Pastoral Psychology, 47, 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022940729136

- Hanh, T. N. (2014). No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming Suffering. Parallax Press.

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2017). Can relationships boost longevity and wellbeing? https://www.health.harvard.edu/mental-health/can-relationships-boost-longevity-and-well-being

- Held, B. S. (2004). The Negative Side of Positive Psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44(1), 9-46.

- Hicks, J. A. & Routledge, C. (Eds.). (2013). The Experience of Meaning in Life: Classical Perspectives, Emerging Themes, and Controversies. Springer.

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. Routledge.

- James, W. (1912). Essays in radical empiricism (Essay II § 1). Longman, Green.

- Joye, S. (2011). Suffering as a discipline? Scholarly accounts on the current and future state of research on media and suffering. LSE, London School of Economic and Political Science.

- Kaufman, S. B. (2020). Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization. Tarcher Perigee.

- Koenig, H. G. (2009). Research on Religion, Spirituality, and Mental Health: A Review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(5), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905400502

- Lomas, T. (2016). Flourishing as a dialectical balance: emerging insights from second-wave positive psychology. Palgrave Commun, 2, 16018. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.18

- Lomas, T. (2021). Life balance and harmony: Wellbeing’s golden thread. International Journal of Wellbeing, 11(1), 50-68. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v11i1.1477

- Maddi, S. R. (2006). Hardiness: The courage to grow from stresses. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(3), 160-168. Doi:10.1080/17439760600619609.

- Mayer, C. H., Vanderheiden, E., & Wong, P. T. P. (Eds.). (In press). The meaning of shame revisited in cultures of the 4th Industrial Revolution.

- Mruk, C. (2008). The Psychology of Self-Esteem: A Potential Common Ground for Humanistic Positive Psychology and Positivistic Positive Psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist, 36(2),143-158. Doi: 10.1080/08873260802111176

- Neff, K. (2015). Self-Compassion: The proven power of being to yourself. William Morrow Paperbacks.

- Robbins, B. (2008). What is the Good Life? Positive Psychology and the Renaissance of Humanistic Psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist 36(2), 96-112. Doi: 10.1080/08873260802110988

- Rosmarin, D. H. (2021). The Connections Paradigm. Templeton Press.

- Schneider, K. J. (2004). Rediscovery of awe: Splendor, mystery, and the fluid center of life. Paragon House.

- Schneider, K. J. (2010). Towards a humanistic positive psychology: Why can’t we just get along. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/awakening-awe/201011/toward-humanistic-positive-psychology-why-cant-we-just-get-along

- Shmotkin, D. (2005). Happiness in the Face of Adversity: Reformulating the Dynamic and Modular Bases of Subjective Well-Being. Review of General Psychology 9(4), 291-325. Doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.4.291

- Thin, N., Tarragona, M., Wong, P. T. P., Jarden, R., Bartholomaeus, J., & Jarden, A. (2017). [Review of the book The pursuit of human well-being: The untold global history, by R. J. Estes & M. J. Sirgy]. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7(1), 84-92. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v7i1.636

- Van Tongeren, D. R., & Van Tongeren, S. A. S. (2020). The Courage To Suffer: a new clinical framework for life’s greatest crises. Templeton Press.

- Waterman, A. S. (2013). The humanistic psychology–positive psychology divide: Contrasts in philosophical foundations. American Psychologist, 68(3), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032168

- Weber, S. R., Pargament, K. I. (2014). The role of religion and spirituality in mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(5), 358-363. Doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000080

- Wikipedia. (2019). Second-wave positive psychology. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second-wave_positive_psychology

- Wong, P. T. P. (2004). Existential psychology for the 21st century. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 1, 1-3.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Positive existential psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 361-368). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9132-6

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Reclaiming positive psychology: A meaning-centered approach to sustainable growth and radical empiricism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 51(4), 408-412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167811408729

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015). What is second wave positive psychology and why is it necessary? Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/what-is-second-wave-positive-psychology-and-why-is-it-necessary/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Chinese positive psychology revisited. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/174/157

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Existential positive psychology. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/179/158 (The second edition of the Encyclopedia of positive psychology was not published because of Lopez’s death, therefore, it was eventually published in my journal [IJEPP])

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016c). How to measure existential meaning [Review of the manuscript of The Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life]. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/how-to-measure-existential-meaning

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016d). Self-Transcendence: A Paradoxical Way to Become Your Best. International Journal Of Existential Positive Psychology, 6(1), 9. http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016e). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017a). Existential theoretical framework. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 1375-1378). New York, NY: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017b). Meaning-centered approach to research and therapy, second wave positive psychology, and the future of humanistic psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist, 45(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000062

- Wong. P. T. P. (2019a). Foreword: From shame to wholeness: An existential positive psychology perspective. In C.-H. Mayer, & E. Vanderheiden (Eds.), The bright side of shame: Transforming and growing through practical applications in cultural contexts (pp. v-ix). Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019b). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

- Wong, P. T. P. (Guest Ed.). (2019c). Special Issue: A Second-Wave Positive Psychology in Counselling Psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 32(3-4).

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020a). Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 According to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). Existential Positive Psychology and Integrative Meaning Therapy. International Review of Psychiatry. DOI: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021). President’s Column: 7 Reasons Why the New Normal May Be Good for You. Positive Living Newsletter. http://www.drpaulwong.com/7-reasons-why-the-new-normal-may-be-good-for-you/

- Wong, P. T. P. (in press-a). Preface: Frankl’s cure for a soulless psychology and a sick society. In N. Krasovska & C.-H. Mayer, Psychobiography of Viktor Frankl. Springer publishing.

- Wong, P. T. P. (in press-b). The Self-transcendence Paradigm for Organizational Growth [Conference Presentation]. Society of Consulting Psychology Annual Conference, Division 13, American Psychology Association. https://www.societyofconsultingpsychology.org/2021-conference-agenda

- Wong, P. T. P., & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). IGI Global.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Roy, S. (2018). Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), Routledge international handbooks. The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology (pp. 142–160). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Worth, P. (2017). The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity [Special issue]. Psychology and Education, 54(3/4). http://www.psychologyandeducation.net/pae/category/volume-54-no-3-4-2017/

- Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., & Arslan, G. (Eds.). (In press). Special Issue: COVID-19 and Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0): The new science of self-transcendence [Special Issue]. Frontiers.

- Yaden, D. B., Haidt, J., Hood, R. W., Jr., Vago, D. R., & Newberg, A. B. (2017) The Varieties of Self-Transcendent Experience [Advanced online publication]. Review of General Psychology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000102

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2021). Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) and global wellbeing: Why it is Necessary During the Age of COVID-19. IJEPP, 10(1), 1-16.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.