Abstract

In this chapter, we propose that suffering is a fertile ground for existentialism and the human quest for meaning, and the suffering hypothesis based on Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy. We also propose that Wong’s existential positive psychology is a promising framework for wellbeing research and meaning-centered interventions. We then explain in detail the benefits of Frankl’s spiritual (noölogical) remedies for human suffering through meeting human beings’ deepest spiritual yearning and need for meaning and transformation. Finally, we introduce recent developments in research that supports and extends the basic concepts of logotherapy. We conclude that Frankl’s pioneer work on meaning provides the most promising spiritual remedies to turn hell into heaven in all cultures.

(This article was written with Don Laird)

Part 1. An Age of Existential crises and the Suffering hypothesis

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has awoken us to the fragility and finitude of human existence (Cowden et al., 2021; Van Tongeren & Showalter Van Tongeren, 2021; Wong, Mayer et al., 2021). The recent Russia-Ukraine war and threats of China’s invasion of Taiwan has made people keenly aware of the catastrophes of nuclear war. In addition to the above existential crises, people are also troubled by pocketbook issues, random violence, runway inflation, and the prospects of global economic recession. In these troubling circumstances, many people, including the youth, may ask “What is the point of striving? How could one be happy in times like these?”

American positive psychology, created in times of peace and prosperity (Seligman, 1999; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), can no longer provide an adequate answer to such anxious questions from the suffering people because it is principally focused on “understanding how people rise from zero to positive eight” (Gable & Haidt, 2005, p. 103).

In contrast, existential positive psychology (EPP), which has its roots in existentialism and ancient wisdom, is fundamentally concerned with the pressing question of how to ameliorate suffering and how to flourish even in the darkest hours (Wong, 2020a, 2021a; Wong, Mayer et al., 2021).

On the surface, EPP appears to be the mere synthesis of existentialism and positive psychology or the second wave of positive psychology (PP2.0). But at a deeper level, it is a new paradigm asking the toughest question of how to achieve ultimate happiness by transforming hell into heaven (Wong & Bowers, 2018). Psychologists have a moral obligation to end people’s suffering and help them create a better future. The suffering hypothesis is designed to show people how to end unnecessary suffering and transform inescapable suffering to strength, happiness, and flourishing.

Suffering is a Fertile Ground for Existentialism and the Quest for Meaning

Human suffering has always been the main focus of existential philosophy and psychology. This isn’t too difficult to understand. We emerged from the Great War and the Great Depression both physically and psychologically bruised. Then came the Holocaust committed by Nazi Germany, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. People began to wrestle with the horrors of the life: the existential crises of human evils, the sorrows, chaos, and absurdities of Being, and the existential anxieties of meaningless, loneliness, death, and the abuse of human freedom.

All human sufferings – physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, social, and economical – and the apparent meaninglessness of human existence became fertile grounds for existentialism (e.g., Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Camus, Sartre, Hildegard, Frankl). Hamm (2015) summarizes as follows:

Just as existentialism took root in Europe much as a response to the meaninglessness the First World War drove into people’s hearts, the Second World War only reinforced this sense of powerlessness, and the meaninglessness of existence. After all, what could one person do? (p. 22)

The pandemic has amplified our existential concerns. The global death tolls and hospitalization rates loudly declare that anyone could be infected and die of COVID-19. Even mandatory lockdown is behind us in most countries. The fear of being infected and testing positive remain a daily possibility. People are afraid to shake hands or hug each other, as if everyone could be a transmitter of COVID-19 or its variants.

No wonder we are witnessing unprecedented levels of anxiety, depression, anger, violence, social turmoil, discrimination, confusion, hate, and anxiety. We read and hear the phrase ‘existential crisis’ so often now that it has become part of our common nomenclature. In the era of COVID-19, even young people begin to question the meaning of life, feeling that it is rather pointless to strive for good grades and good jobs, because in the end, we all die.

However, existential writings are far from the nihilistic despair they are accused of being. In effect, they reflect just the opposite. From the lens of existentialism, meaning offers us a heroic way to survive and experience a deeper kind of happiness. Hamm (2015) writes:

Joy is a fundamental part of the existential writings of several authors in the tradition… It is in this sense that existentialism offers a possibility of joy not as a needle in a haystack, but rather as a diamond in the rough. (p.7)

More recently Roncero (2021) makes a more explicit cases that an existential crisis can be an opportunity for positive transformation.

“Existential crises are often be associated with a negative impact on one’s life, but we forget the positive effect it can have. An existential crisis means we have the opportunity to get back in touch with our values, meaning and purpose, and with what we want to make of our lives. This can help us evaluate, plan and adapt our actions and direction in order to lead the life we want and will be happy with.”

As counterintuitive as it may seem, embracing inescapable suffering is far more adaptive than to avoid it. According to existentialism, paradoxically, we become an authentic version of ourselves and flourish only when we are aware of our mortality.

Jean Paul Sartre (1943/1989) penned, “Human life begins on the far side of despair.” The answer to life’s greatest questions is found within creative action and meaning. Similarly, Albert Camus wrote:

“In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy. For it says that no matter how hard the world pushes against me, within me, there’s something stronger – something better, pushing right back.”

Viktor Frankl (1946/1985) was the first psychotherapist to fully articulated both the power of meaning and the obstacles of finding meaning. Observing firsthand that although many of his fellow prisoners perished as a direct result of crimes committed by the Nazis, others died by suicide or withered when they had lost their will to survive.

However, those who found meaning—or a purpose to remain alive— were far better equipped to withstand suffering and torment at the hands of their captors. Despite the heartbreak and horror of it all, Frankl noted that they persisted because they saw meaning and purpose in their suffering. It helps us recognize the importance of why finding meaning in the face of suffering is fundamental to our existence as a species (Frankl, 1946/1985):

We must never forget that we may also find meaning in life even when confronted with hopeless situation, when facing a fate that cannot be changed. For what then matters is to bear witness to the uniquely human potential at its best, which is to transform a personal tragedy into a triumph, to turn one’s predicament into a human achievement. (p. 116).

The Suffering Hypothesis and the Ultimate Happiness

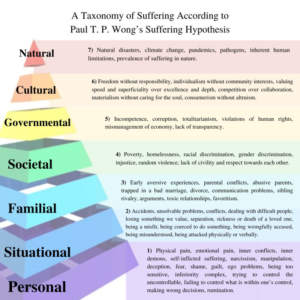

According to the suffering hypothesis, life is full of suffering, and it is an inescapable part of human existence, as shown in Figure 1. Whether we are confronted with natural disasters, pandemics, a soulless and heartless culture of brutal competitions, corrupt government, or tormented by our inner demons of greed, envy, anger, or inferiority complex, we are carrying an enormous load of cares in our daily struggles for survival and happiness.

In this graph, suffering cause by nature, culture, government, or society are mostly beyond personal control. Frankl would suggest to use attitudinal values to cope with those macro problems or to change oneself in order to accommodate these problems. The person can also exercise social responsibility to collaboratively improve our social ails. The last three layers (familial, situational, and personal) indicate that most of the problems are within the person’s control. Therefore, they have the responsibility to resolve the issue.

Barring any mishap, even an ordinary day can drain one’s energy with its everyday hassles and frustrations of working with fake or unreasonable people. Suffering is everywhere, no matter what you do or where you go. One can be easily overwhelmed by the enormity and complexity of suffering, especially most of our suffering are beyond of human control. Thus, the brutal truth is that to live is to suffer, and to suffer is to learn how to turn it into strength and flourishing.

Figure 1

A Taxonomy of Suffering According to Paul T. P. Wong’s Suffering Hypothesis

The main attraction of our suffering hypothesis is that it is not suffering but how we respond to it that really matters. In other words, suffering can either destroy us or make us better and stronger. Inspired by Frankl’s testimony and teaching, we affirm that we have the capability to transform suffering into strength and add deeper meaning to our lives:

“The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity – even under the most difficult circumstances – to add a deeper meaning to his life.” (Frankl, 1946, p. 76).

It is important to note that Wong’s (2003, 2021b) suffering hypothesis complements Jonathan Haidt’s (2006) happiness hypothesis because the suffering hypothesis captures both functions of the soul, which is (1) to satisfy the soul’s spiritual yearning for happiness and (2) to satisfy the soul’s ultimate need to come to terms with the dark side of human existence. These two functions need to work together to achieve healing and flourishing according to the dual-system model (Wong, 2012).

It is through integrating happiness and suffering that we can find the middle way – to be safely happy and to suffer joyfully (Soper, 2020; Wong, 2011, 2022a, submitted). It is through integration that we discover that ultimate happiness can approximated by going through the gates of hell and moving upward towards heaven.

According to the suffering hypothesis, happiness is so intractable because life is always a mixture of happiness and suffering. No one is immune from pain, and we all live under the shadow of suffering and death. Furthermore, there is often a complex and dynamic relationship between happiness and suffering. There is a Chinese saying: “The extreme form of happiness produces sorrow.” Just as happiness may lead to suffering, so does suffering may lead to happiness.

That is why the suffering hypothesis posits the following:

- The pursuit of happiness can be a cause of suffering because of (a) frustration of unrealistic expectation and unexpected obstacles, and (b) fear of losing what one values most.

- The end of suffering is the beginning of true happiness because learning wisdom and virtues is needed for mature happiness.

- We need wisdom and virtue because it leads to self-control which helps us avoid unnecessary suffering.

- We need courage and virtue to endure, overcome, and transform inescapable suffering.

- We rejoice in voluntary suffering for a worthy cause or someone we love more than ourselves.

“He who does not know of sorrows / in this valley of sorrows, / does not know of good things, / nor has he tasted love, / for sorrows is the garb of lovers.” (Crisogono De Jesus, 1955/1958, Chapter 10)

Part 2: Frankl’s Spiritual Remedies

Viktor Frankl occupies a unique place in the chronicles of psychology. While other psychologists do research on the behavior, cognition, or emotion of people through observation or self-report, Frankl studied real people in their struggles for survival and wholeness in a cruel world.

His book Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl, 1946/1985) remains a best seller because it touches people’s hearts and souls and shows them how to find meaning whatever their circumstances. It is a shame that most research psychologists working on meaning are not familiar with the deep wisdom of Frankl’s work on meaning.

The world seems to have gone wild, bent on self-destruction, with every person free to pursue their unbridled egotistic desires. What is the most promising solution to the perennial problem of human suffering? What is the best way to transform the hell of human evil, violence, and mental illness to the heaven of peace, love, and joy?

We propose that Frankl’s cure (Wong, 2020b, 2021c, 2021d) may shows us the way. Frankl’s logotherapy is both timeless and transcultural, because it speaks to the universal spiritual yearnings of human beings and discovers the universal human capacities to meet their spiritual needs for meaning:

Logotherapy’s primary goal is to describe, phenomenologically, the essence of being via its different names, such as “Dasein,” “Tao,” “self-realization,” “Zen-consciousness,” and so on, and take this into consideration in the therapeutic encounter. (Ko, 1980)

Frankl’s therapy is essentially a spiritual therapy in its assumptions and applications because of people’s struggles with suffering and their inner “existential vacuum,” even in the best of times.

Existential Vacuum as a Source of Human Suffering and Bad Behavior

Frankl introduces the term “existential vacuum” to describe the condition of people who, for various reasons, do not have meaning in their lives and consequently experience boredom, emptiness, and loneliness. The lack of meaning and spiritual values, if unattended over a long time, may eventually results in an “existential vacuum.” People may resort to all kinds of distractions, even unethical and illegal activities, to fill that inner void.

Frankl considers it a noögenic disorder on the spiritual level, which calls for a spiritual remedy. This existential vacuum accumulates and expands as people continue to reject what is meaningful in favor of what is expedient or meets the needs of their lower or baser instincts. As a result, weeds take over their soul in terms of bad habit, addiction, indulgence in pleasures, pride, and egotism. Logotherapy is designed to help awaken people’s deep-seated need for meaning and spirituality.

Frankl’s Anthropology and Spiritual (Noölogical) Dimension

Frankl has a high view of human being and opposes the prevailing view that we are “nothing but.’ His dimensional ontology recognizes the somatic, psychological, and spiritual dimension, but he holds a holistic view that these three dimensions are interrelated with the spiritual dimension distinguishing us from other animals.

Against the dominant voices in the academia of Vienna (Freud’s will to pleasure and Adler’s will to power), Frankl (1946/1985) struggled to make his voice heard, to bring to attention the importance of the will to meaning as a spiritually rooted motivation. It is the spiritual yearning for meaning that enables us to transcend our physical and mental limitations. To ignore one’s spiritual dimension, all kinds of problems may ensue, as we have already noted earlier.

There are 3 aspects of spirituality: (1) the will to meaning, which is one’s spiritual motivation; (2) the meaning of life even in times of suffering, and (3) the capability to choose the spiritual orientation (Ryan, 2019).

The will to meaning is present in every person. The Unheard Cry for Meaning (Frank, 1978) indicates all human beings are crying out for meaning, but their cries are muffled by the voices of the secular world and egotistic desires. Everyone has the freedom and responsibility to reflect on one’s own unhappy life and choose to re-orient towards a more meaningful and spiritual existence:

“One cannot experience meaning in life without discovering the meaning of suffering:

The meaning of suffering-unavoidable and inescapable suffering alone, of course–can be the deepest possible meaning. The art of being human is learning how to deal with those painful moments. These moments require an attitude of inner willingness to suffer, while remaining in touch spiritually with one’s own extended dimensions…When this inner struggle becomes calm, one can experience how the lower somatic and psychological dimensions influence the higher spiritual dimension but do not produce or cause it. One can discover despair despite success, and fulfillment despite failure.” (Marseille, 1997)

“It is one of the basic tenets of logotherapy that man’s main concern is not to gain pleasure or to avoid pain but rather to see a meaning in his life. That is why man is even ready to suffer, on the condition, to be sure, that his suffering has a meaning.” (Frankl, 1946/1985, p. 117).

The Spiritual Yearning for Ultimate Meaning

Frankl recognizes three kinds of meaning – meaning of the moment, one’s meaning in life as a whole, and the ultimate meaning (Wong, 2014).

Belief in the ultimate meaning of life is necessary for logotherapy’s basic tenet that life has intrinsic meaning up to the last breath. It reminds us of William James’ affirmation of meaning: “Be not afraid of life. Believe that life is worth living and your belief will help create the fact” (James, 1896, Section IX).

Ultimate meaning makes the meaning of suffering possible. With a defiant attitude, we can still look at the shining stars in the darkest night and affirm one’s faith in life’s intrinsic and ultimate meaning:

“The grandiose order, I believe, is what Frankl understands by logos, ultimate meaning. We can never hope to ‘find’ it in its totality, we can only pursue it to the best of our abilities” (Fabry, 1994, p. 35)

Furthermore, Wong (2014) explained Frankl’s idea in this way:

“In a sense, ultimate meaning belongs to the spiritual and transcendental realm. From time to time, we are given a glimpse of the glorious possibility that there is ultimate meaning and purpose in life. However, as we go through different stages of life and different experiences, our understanding evolves. This unending quest for ultimate meaning is simultaneously both uplifting and trying, and it has been at the centre of the human search for meaning since antiquity.” (Wong, 2014)

“If you are aware of ultimate meaning, in either a religious or a secular context, you will be able to respond meaningfully to the offerings of the moment because you have a built-in compass that points toward meaning. If you are not aware of ultimate meaning, you will respond to the meaning of the moment as best you can, and in the course of your life you will gradually approach understanding of ultimate meaning.” (Fabry, 1988)

The Three Spiritual Values of Meaning

According to Frankl (1986), there are three values or pathways to experience meaning:

- Creative Value. What I give the world with the value I create by doing what I do with all my heart, all my heart and all my soul, and placing a stamp of my unique personality and imagination to the work, regardless of the occupation. Therefore, my work has meaning, because I do it as if unto God.

- Experiential Value. What I receive from the world with an attitude of gratitude and a humble attitude of learning some important lesson from God. This has spiritual value, because it takes one away from what makes me happy, but what stretches me and makes me become what I am meant to be.

- Attitudinal value. What stance I take towards fate or suffering. “But most far-reaching are the attitude values which can be actualized to one’s last breath.” (Marseille, 1997). “Man is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips. (Frankl, 1946/1985, p. 134).

The Human Capacities to Experience and Express the Spiritual Dimension

Frankl (1946/1985) holds that there are three capabilities that enable us to express and experience our spiritual dimension:

- Self-determination. The courage and freedom of the will to take personal responsibility for choosing to do what is right and what is meaningful rather than what gives us pleasure or power. This is a spiritual choice – to choose good rather then evil.

“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart—and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains…an uprooted small corner of evil.” (Solzhenitsyn, 1974/2003)

- Self-detachment. The practice of pausing and keeping calm in order to get in touch with our conscience, and with God, allows us to do the right thing between stimulus and response. It is a very important skill to enable us to step back from our immediate concerns and the environment. We are not our problems. We are who decides how to best respond to all the events that happen to us. This little separation allows us to consult conscience and our forebrain before responding emotionally or habitually.

- Self-transcendence. The essence of human existence. As Frankl (1949/1986) says:

“Being human is always directed, pointing to something or some one other than oneself: to a meaning to fulfil lor another human being to encounter a course to serve or a person to love. Only to the extent that someone is living out this self-transcendence of human existence is he truly human or does he become his true self.”

Here is a good description of Frankl’s (1946/1985) experience of self-transcendence in the Nazi death camp:

“Another time we were at work in a trench. The dawn was gray around us, gray was the sky above, gray was the snow in the pale light of dawn, gray the rags in which my fellow prisoners were clad & gray their faces. I was struggling to find the reason for my suffering, my slow dying.

In a last violent protest against the hopelessness of imminent death, I sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world & from somewhere I heard a victorious ‘YES’ in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment, a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable gray of a dawning in Bavaria. “Et lux in tenebris lucet”—and the light shineth in the darkness and the darkness can never overcome it.’ (pp. 40-41, emphases in the original)

Elsewhere, Wong, Arslan and colleagues (2021) fully describe the different dimensions of self-transcendence and explain why it is important for us to become fully human by going beyond and above our physical and mental limitations and transcend all the negative forces that hold us back.

The Power of Meaning and Spirituality as an Antidote to Egotistic Desires and Human Suffering

What can we do about rampant human evil and widespread human suffering? Something needs to be done before more innocent people get killed and more people get addicted to drugs or commit suicide. Something needs to be done to help people with mental illness. Perhaps, we should at least give spirituality a chance. Perhaps most of the human and societal problems stem from the fact that we are like fish out of water in a secular and materialistic society. We have forgotten our spiritual roots and our need to be connected with out true self, with people, and with God or Dao.

At a time when the world is full of disinformation and technological progress, we should expose all students to the spiritual power of meaning transformation.

We need spiritual wisdom or moral transformation, one person as a time. We are not asking for a religious conversion to any particular faith tradition. We are proposing that Frankl’s view of a universal yearning for meaning, and his meaning interventions, offer the possibility of awakening people’s spiritual dimension, and showing them the path to spiritual transformation through meaning.

Frankl takes ethics very seriously. After the brutalities of Hitler, Frankl (1988) wrestled with the question how to prevent another Hitler and how to educate people to a more ethical or moral to treat each other (Wong & Reilley, 2017a, 2017b). Frankl’s spiritual remedies should result in loving our neighbours as ourselves rather than instruments to be used for our own gains.

Christian Miller (2019) had made a compelling case that all of us are mixed bags of good and evil, and it is very important to become a better person and close the character gap. Of all the options to improve our character, Frankl’s spiritual conception of meaning as self-detachment and self-transcendence is worth our serious consideration.

One cannot reason one’s way to a virtuous life; nor can we find scientific guidance to live a moral life, because science is about the physical or natural world, not the moral realm. In the final analysis, one’s moral mooring needs to be grounded in a transcendental reality, God, or Tao. To activate our spiritual dimension in order to get in touch with this ultimate meaning is a good start.

One moment of awareness can last a lifetime. One moment of responsible choice of will to meaning can change one’s destination. Nothing can imbue life with more meaning and significance than such moments of encounter with God or the transcendental reality.

How to live a meaningful life is not just a matter of philosophical discussion or a matter of following the scientific findings of armchair psychology, but an urgent matter of how to be become the best version of ourselves by become our true selves, guided by conscience, compelled by compassion, and consumed by the passion to pursue one’s calling or what really mattes.

It is a practical spirituality of walking on the narrow path of dirt but with our eyes towards an ideal that lifts up our spirit and fills our hearts and bellies with passion. It is the practical spirituality of making the best use of each day and the best use of every opportunity to turn hell into heaven. Frankl’s spiritual remedies will not work if one treats logotherapy as head knowledge, rather than a blueprint or road signs for living a spiritually rooted meaningful life.

The universal spiritual hunger is evident not only in our own lives but in research. We can have spirituality without religion, and we can also have religion without belief in any set of dogmas (Borg, 1997; Goff, 2022).

In his book The God We Never Knew, Borg (1997) affirmed the existence of God, but a God whose nature could not be expressed in human language, and hence who is not literally ‘all-knowing’ or ‘all-powerful.’

In the 2022 Gallup Survey:

Gallup found 81% of Americans expressing belief when asked the simple question, “Do you believe in God?” This was down from 87% in 2017 and a record low for this question first asked in 1944, when 96% believed. It reached a high of 98% in the 1950s and 1960s. (Saad & Hrynowski, 2022)

In a recent article on spirituality’s contribution to mental health, Sallcru (2022) defines spirituality as the transcendental ways of fulfilling human potential. After reviewing the extensive research evidence on the important role of spirituality in mental health and effective psychotherapy, Sallcru concludes: “From a personal perspective and professional capacity, I dare to say (without exaggeration) that spiritual practices could save anyone years of suffering and/or psychotherapy.”

Therefore, there is enough empirical evidence and professional consensus that Frankl’s spiritual remedies are aligned with human nature and contribute to mental health. However, Frankl’s teaching is against the nihilism and narcissism supported by a secular, materialistic culture.

We have witnessed the devastations of developing only the brain power of intellect while starving the soul; and it is time for the wisdom of the soul and the virtues of living a purpose-driven and meaning-centered life (McLaughlin & McMinn, 2022; Wong, 2022). In the eternal struggle between good and evil, a resurgence of spirituality and meaning may be our best hope of tipping the balance towards the good for individuals and society.

Part 3: Recent Developments

Logotherapy and the new science of suffering received increased attention during the pandemic (Chen et al., 2021; Van Tongeren & Showalter Van Tongeren, 2021; Wong, 2020b; Wong, Mayer et al., 2021). These publications offer a glimpse of the progress made in extensions of logotherapy and the new science of suffering.

This chapter simply focuses on Wong’s research in extending Frankl’s work and providing a framework of existential intelligence and meaningful living. This framework covers five major sections:

- Accept life as it is: Life is full of suffering and hardship. Awareness of this reality better prepares us for the future and gives us the mindset that a good tomorrow depends on working hard today (see Figure 2). This principle also includes accepting ourselves fully, including our dark side and our mortality.

Figure 2

A Good Tomorrow Depends on Working Hard Today

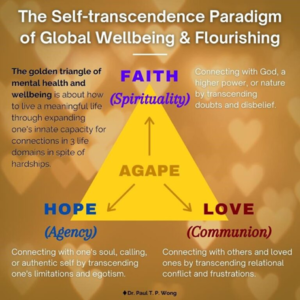

- Believe in creating a preferred future through actualizing my potential, depending on others, and seeking help from God/Tao/Higher Power. Supporting Frankl’s (1946/1985) conception of ultimate meaning or super-meaning: “This ultimate meaning necessarily exceeds and surpasses the finite intellectual capacities of man; in logotherapy, we speak in this context of a super-meaning. What is demanded of man is not, as some existential philosophers teach, to endure the meaninglessness of life, but rather to bear his incapacity to grasp its unconditional meaningfulness in rational terms. Logos is deeper than logic.” (Frankl, 1946/1985, p. 141) Wong and Wong (2019a) and Wong (2020b) articulate the power of faith in providing a sense of consolation, security, and guidance regardless of how horrible the circumstances. Elsewhere, Wong (2016) also wrote about the responsibility of becoming the best version of ourselves through self-transcendence. To be mentally healthy, we need connections not just with our soul, but with others and with God (Rosmarin, 2021). These three connections represent the three pillars of positive mental health as the golden triangle in Figure 3.

Figure 3

The Golden Triangle

- Committed to personal growth and achieving one’s life goal. Belief needs to be followed by actions in order to narrow the belief-behavior gap or character gap (Miller, 2018). This involves make the best use of one’s time to become better, wiser, and stronger through the discipline of hard work (Wong, 2019a). This principle also involves the double-vision strategy of keeping one’s feet on the solid ground but keeping one’s eyes on the highest ideals, or what is personal is universal and vice versa in terms of human predicaments (Wong, 2015).

- Discover the resources available and the unexplored side of oneself. According to Wong and Worth’s (2017) deep-and-wide hypothesis, one does not know how strong or resourceful one is until one dig deeper and wider. Wong (2019b) also reports numerous studies demonstrating that both animals and humans can be trained to be extremely persistent and resourcefully through increasing demand. Furthermore, we also discover the unexplored areas of oneself and the inexhaustible grace and resource in God for the beliefs who pray to him for help.

- Enjoy the intrinsic reward of living a meaningful life and the joy of turning hell into heaven. By practicing the above four principles of existential positive psychology and meaning therapy, one will reap the following benefits:

- Know how to suffer well and end unnecessary suffering. As Tolle (2010) noted:

- Know how to maintain hope even in hopeless situations (Leung et al., 2021; Wong, 2009).

- Learn wisdom and virtue (Wong 2022a).

- Learn how to maintain inner peace, balance, and harmony regardless of the situation (Wong & Bowers, 2018).

- Live the best possible life of depth and tranquillity in a troubled world (2022b). The ABCDE strategy is the main intervention for integrative meaning therapy (Wong, 2010) which incorporates the basic principles of logotherapy. Every step requires the exercise of the spiritual freedom and responsibility to pursue the core spiritual value of will to meaning.

Conclusion

Even though the world seems to be full of suffering and evil, and we often wonder whom we can trust, there is hope. Miller (2018) provides a compelling case that we are all a mixed bag of good and evil, and no matter how bad a person may be, he still has the image of God in him and is capable of becoming a better person.

As illustrated in this chapter, Frankl’s logotherapy and Wong’s five principles for spiritual transformation (Acceptance, Belief, Commitment, Discovery, and Enjoyment) provide a promising way of positive education program to complement the existing C’s of youth development program (Lerner, 2009).

We offer an existentially oriented and spiritually rooted program based on the foundation of Frankl’s logotherapy. It is holistic rather than one dimensional. It accepts the dark reality yet believes in the power of faith in God; it embraces suffering yet believe that one needs to experience hell in order to attain heaven. Instead of offering a fast and easy way to achieve positive transformation, it advocates the slow and difficult way of making the tough choices and the lifelong disciple of cultivating wisdom and virtue.

Wong (2021c) points out that our society often prefers instant gratification and quick fixes rather than taking the long view of learning how to live and how to endure hardships and resolve problems:

For many people, concepts like responsibility, self-transcendence, and suffering are much more difficult to understand and accept than happiness, success, and flourishing. It is difficult because most people view life through the lens of hedonism, materialism, and egotism. They tend to react instinctively by rejecting and avoiding anything that makes them uncomfortable. They prefer distractions or instant relief to the bitter medicine provided by Frankl. (foreword, p. v-vi)

My recent extensions of Frankl’s work present a very different vision of positive youth development with its emphasis on meaning and spirituality as the two main pillars. We believe that this more realistic and spiritual worldview can better prepare our young people for a difficult present and an uncertain future. When we combine individual responsibility and effort with faith in God’s spiritual resources and protection, we are undefeatable.

We want to conclude this chapter with a quote from Guttmann (2008), which highlights the spiritual roots of Frankl’s logotherapy:

According to the theory of logotherapy, the struggle to achieve meaning in life is the most important struggle…As long as one struggles, one is alive emotionally. One gets more mature. More seasoned, and richer spiritually by this struggle. Sisyphus found meaning in his suffering, and that meaning gave him the strength to carry on his suffering and find a few minutes of grace. (p. 61)

“Yes” to suffering, “Yes” to meaning, and “Yes” to the joy of living; thanks to the amazing grace of spiritual power. In the end, we are responsible for our wellbeing and our future, because we are the products of our choices. Successful execution of the ABCDE principles depends on spiritual activation of our faith and courage to say “Yes” to life, and “Yes” to doing the right thing no matter what.

References

- Borg, M. J. (1997). The God we never knew: Beyond dogmatic religion to a more authentic contemporary faith. Harper Collins.

- Camus, A. (1952). Return to Tipasa. https://genius.com/Albert-camus-return-to-tipasa-annotated

- Chen C.-H., Chang, S.-M., & Wu, H.-M. (2021). Discovering and approaching mature happiness: The implementation of the CasMac model in a university English class. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.648311

- Cowden, R. G., Rueger, S. Y., Davis, E. B., Counted, V., Kent, B. V., Chen, Y., VanderWeele, T. J., Rim, M., Lemke, A. W., & Worthington, E. L., Jr. (2021). Resource loss, positive religious coping, and suffering during the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective cohort study of U.S. adults with chronic illness. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2021.1948000

- Crisogono De Jesus. (1958) The Life of St. John of the Cross [Vida de San Juan de la Cruz] (K. Pond, Trans.). Longmans and Harper & Brothers (Originally published in 1955)

- Fabry, J. (1988). Guideposts to meaning: Discovering what really matters. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications.

- Fabry, J. B. (1994). The pursuit of meaning (New revised ed.). Institute of Logotherapy Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1978). The unheard cry for meaning: Psychotherapy and humanism. Touchstone.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s Search for Meaning. Simon & Schuster. (Originally published in 1946)

- Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy. Second Vintage Books. (Originally published in 1949)

- Gable, S. L., & Haidt, J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Review of General Psychology, 9, 103 – 110. Doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

- Goff, P. (2022, August 1). Why religion without belief can still make perfect sense. Psyche. https://psyche.co/ideas/why-religion-without-belief-can-still-make-perfect-sense

- Guttmann, D. (2008). Finding meaning in life, at midlife and beyond: Wisdom and spirit from logotherapy. Praege Inc.

- Haidt, J. (2006). The happiness hypothesis: Finding modern truth in ancient wisdom. Basic Books

- Hamm, R. (2015). Its all uphill from here: Finding the concept of joy in existential philosophy and l literature. Purdue University: Purdue e-Pubs. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI3719195/

- James, W. (1896). The will to believe. An address to the Philosophical Clubs of Yale and Brown Universities. http://educ.jmu.edu//~omearawm/ph101willtobelieve.html

- Ko, B. (1980). Zen and the noetic dimension. In S. A. Wawrytko (Ed.), Analecta Frankliana: The proceedings of the First World Congress of Logotherapy (pp. 295-300). Institute of Logotherapy Press.

- Lerner, R. M. (2009). The positive youth development perspective: theoretical and empirical bases of a strengths-based approach to adolescent development. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 149-163). Oxford University Press.

- Leung, M. M., Arslan, G., & Wong, P. T. P. (2021). Tragic optimism as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering and the psychometric properties of a brief version of the life attitudes scale (LAS-B). Frontiers, 12, 646843. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646843

- Marseille, J. (1997). The spiritual dimension in logotherapy: Viktor Frankl’s contribution to transpersonal psychology. The journal of transpersonal psychology, 29(1), 1-12. https://www.atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-29-97-01-001.pdf

- McLaughlin, P. T., & McMinn, M. R. (2022). A time for wisdom: Knowledge, detachment, tranquility, transcendence. Templeton Press.

- Miller, C. (2019). The character gap. Oxford University Press.

- Roncero, A. (2021, August 30). What is an existential crisis, and how do you overcome it? BetterUp. https://www.betterup.com/blog/what-is-an-existential-crisis

- Rosmarin, D. H. (2021). The connections paradigm. Templeton Press.

- Ryan, W. F. (2019). Chapter 3: The elements of ethics in Viktor Frankl. Ultimate Reality and Meaning. https://doi.org/10.3138/uram.36.1-2.47

- Saad, L., & Hrynowski, Z. (2022, June 24). How many Americans believe in God? News Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/268205/americans-believe-god.aspx

- Sallcru, S. (2022). Spirituality and its contribution to mental health. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psychology-insights-new-world/202208/spirituality-and-its-contribution-mental-health

- Sartre, J.-P. (1989). No exit and three other plays (S. Gilbert, Trans). Vintage. (Originally published in 1943)

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1999). The APA 1998 annual report. American Psychologist, 54(8), 537-568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.537

- Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. The American psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

- Solzhenitsyn, A. (2003). Gulag Archipelago. Vintage. (Originally published in 1974)

- Soper, C. A. (2020). The evolution of life worth living: Why we choose to live. C. A. Soper.

- Tolle, E. (2010). Stillness speaks. New World Library.

- Van Tongeren, D. R., & Showalter Van Tongeren, S. A. (2021). Finding meaning amidst COVID-19: An existential positive psychology model of suffering. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 641747. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641747

- Wong, P. T. P. (2003). Finding happiness through suffering [President’s Column]. Positive Living Newsletter. https://www.meaning.ca/archives/presidents_columns/pres_col_aug_2003_happiness-through-suffering.htm

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85–93.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 52(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). Viktor Frankl’s meaning seeking model and positive psychology. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in existential and positive psychology (pp. 149-184). Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015). Meaning therapy: Assessments and interventions. Existential Analysis, 26(1), 154-167.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Self-Transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 6(1), 9. http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019a). Inspirations for difficult times (L. C. J. Wong, Ed.). Toronto, Canada: INPM Press. Chapters 8 (The best investment in life – character) and 10 (We are spiritual beings on an earthly journey)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019b, May 7). Learned helplessness or learned resourcefulness? Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. http://www.drpaulwong.com/learned-helplessness-or-learned-resourcefulness/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020a). Existential positive psychology and integrative meaning therapy. International Review of Psychiatry. Doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). Made for resilience and happiness: Effective coping with COVID-19 according to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021c). What is existential positive psychology (PP 2.0)? Why is it necessary for mental health during the pandemic. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 10(1), 1–16. https://www.meaning.ca/ijepp-article/vol10-no1/what-is-existential-positive-psychology-pp-2-0-why-is-it-necessary-for-mental-health-during-the-pandemic/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021b, December 20). The suffering hypothesis: How the new science supports the ancient wisdom of meaningful suffering [President’s Column]. Positive Living Newsletter. https://www.meaning.ca/article/the-suffering-hypothesis-how-the-new-science-supports-the-ancient-wisdom-of-meaningful-suffering/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021c). Preface: Frankl’s cure for a soulless psychology and a sick society. In N. Krasovska & C.-H. Mayer, Psychobiography of Viktor Frankl. Springer publishing.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021d). The Frankl cure for the 21st century: Why self-transcendence is the key to mental health and flourishing. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 41(2), 33-50. Doi: 10.31234/osf.io/tbx3f

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022a). The wisdom of the soul: The missing key to happiness and positive mental health? [Review of the book A Time for Wisdom: Knowledge, Detachment, Tranquility, Transcendence, by P. T. McLaughlin & M. R. McMinn]. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 11(1). https://www.meaning.ca/ijepp-article/vol11-no2/the-wisdom-of-the-soul-the-missing-key-to-happiness-and-positive-mental-health/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022b). The best possible life in a troubled world: The seven principles of self-transcendence [亂世中活出最好的人生:自我超越的七項原則]. Positive Psychology in Counseling and Education. Doi:10.30099/PPCE.202206_(1).0001

- Wong, P. T. P. (submitted). Towards a general theory of mental health and wellbeing [Review of the book The Evolution of Life Worth Living, by C. A. Soper]. International Journal of Wellbeing.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). IGI Global.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Reilly, T. (2017a, August 15). Frankl’s self-transcendence model and virtue ethics — Part 1 of 2. The Virtue Blog. https://thevirtueblog.com/2017/08/15/frankls-self-transcendence-model-and-virtue-ethics-part-1-of-2/ (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P., & Reilly, T. (2017b, August 16). Frankl’s self-transcendence model and virtue ethics — Part 2 of 2. The Virtue Blog. https://thevirtueblog.com/2017/08/15/frankls-self-transcendence-model-and-virtue-ethics-part-2-of-2/ (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P., & Worth, P. (2017). The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity [Special issue]. Psychology and Education, 54(3/4). http://www.psychologyandeducation.net/pae/category/volume-54-no-3-4-2017/

- Wong, P. T. P., Arslan, G., Bowers, V. L., Peacock, E. J., Kjell, O. N. E., Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T. (2021). Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the Self-Transcendence measure-B. Frontiers, 12, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648549

- Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., & Arslan, G. (Eds.). (2021). COVID-19 and Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0): The new science of self-transcendence [Special Issue]. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/14988/covid-19-and-existential-positive-psychology-pp20-the-new-science-of-self-transcendence

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. & Laird, D. (2024). The suffering hypothesis: Viktor Frankl’s spiritual remedies and recent developments. In C. McLafferty, Jr. and J. Levinson (Eds.), Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute of Logotherapy Frankl Institute Vienna (Vol. 2; pp. 93-110). Springer Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-48922-8_6

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.