At times, the film comes close to being a farce or slapstick, but then quickly it returns to its premise of grappling with existential issues. It is a daunting task to provide a serious social commentary on American culture in a comic context, but David Owen Russell has pulled it off. In sum, I Heart Huckabees defies traditional movie genres. Perhaps it is best characterized as one of those avant-garde, artful, and intelligent films produced by a small group of talented and innovative filmmakers such as Paul Thomas Anderson, Spike Jonze, and Sofia Coppola.

I Heart Huckabees offers a unique kind of viewing experience—it is at times too slow and too fast, irritating but charming, nonsensical but witty, shallow and yet profound. No wonder it gets such mixed reviews from mainstream movie critics. But the tension between polarities and the potential for integration drives the movie. The best way to enjoy I Heart Huckabees is to approach it with curiosity and open-mindedness. Just try to enjoy the ride, even though it gets messy and bumpy from time to time. At the end, you may discover that it has been a rewarding adventure. The aftertaste is even better.

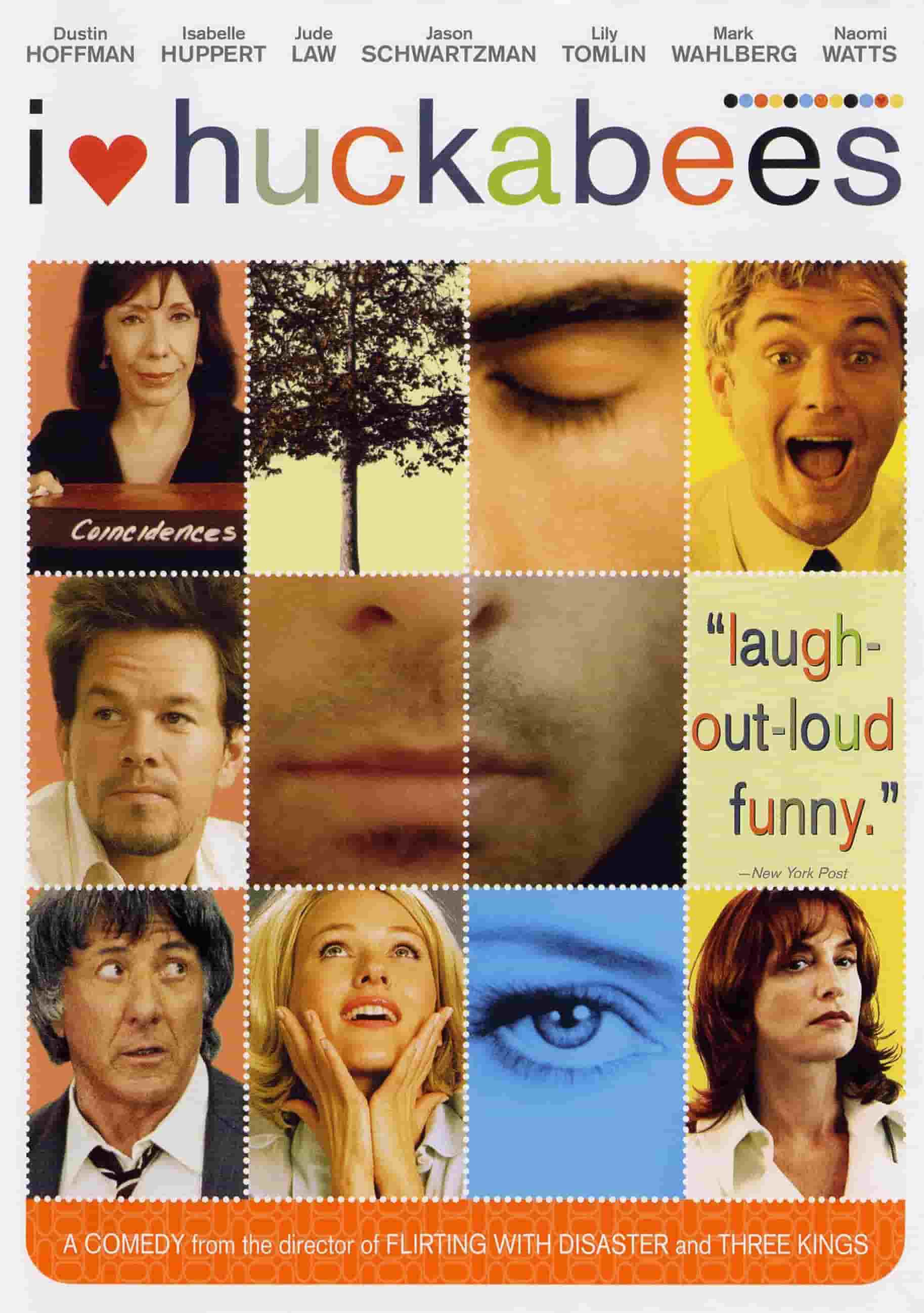

The Cast of Characters

This film features an all-star cast. The strong performances carry the day and make the movie believable, even though they are quirky, goofy, and comical. In real life, you would never meet any of these characters. You may have difficulty relating to them, because of their eccentricity and bizarre behaviors, yet you cannot help but believe them, seduced by their sincerity.

The central character is Albert, played by Jason Schwartzman in his usual deadpan face. As a poetry-writing environmental activist, Albert seems to be a born loser. His poetry is atrocious, and his acts of saving the environment are totally inept (e.g., placing a tree in a parking lot). Like a remnant from the 1960s, he is a boomer hippie, totally out of place in a fast-paced consumer culture. He rides a bicycle; he has no money, no career, and no close relationships. He seeks out “existential detectives,” ostensibly because of coincidental meetings with a tall African man, but the underlying problem is a profound sense of failure and meaninglessness. He does not know who he is, and he is willing to try anything to find himself. He is a sympathetic character. One admires his idealism but feels sorry for his naïveté and incompetence.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is Brad, played by Jude Law. Brad is a marketing executive of a megastore called Huckabees, which sells everything under the sun. Brad has it all—good looks, a lovely house, a beautiful girlfriend (the store’s in-house model, Dawn), and a great career. He is a manipulative control freak with a charming persona. He is quite content with his life and not at all interested in existential questions, as long as life unfolds smoothly. He is an unsavory character who epitomizes what is wrong with the current American culture—he is materialistic, indulging, self-centered, and profit-driven as well as shallow and empty inside. He hires the existential detectives to investigate Albert, but when they probe into Brad’s own life, his world falls apart and he is forced to confront his faked existence.

Tommy Corn, an environmentally conscious fireman, is played by Mark Wahlberg. Tommy’s obsession with the negative impact of petroleum on society and his dark existential thoughts alienate him from his wife, who moves out on him. In a heated exchange with Tommy, his wife blurts out a pointed question: “If nothing matters, how can I matter?” This is one of the conundrums that Tommy tries to resolve. He is introduced to Albert by Vivian Jaffe, an existential detective, because Tommy is the “other” of Albert—both are frustrated by their inability to adequately address environmental and existential concerns. Tommy asks Albert on their first meeting, “Why do people only ask themselves deep questions when something bad happens, and then they forget all about it later? How come people are self-destructive?” These are the kinds of questions director Russell has been struggling with since 9/11; Tommy is simply Russell’s mouthpiece. The masculine, earnest Tommy is probably the most likable and least weird character in I Heart Huckabees.

The existential detectives Bernard and Vivian Jaffe, played by Dustin Hoffman and Lily Tomlin, are the most original characters in the film. They have a very unorthodox approach in helping their clients resolve their personal issues: They literally spy on them, probing into the details of their private lives and family backgrounds. They have the capacity and tenacity to totally disrupt or deconstruct their clients’ lives to the point that the client has to change for the better. One fact stands out: They are the only stable and loving couple in the film; they frequently show affection for each other in front of their clients.

These eccentric characters are joined by a French woman, Caterine Vauban (Isabelle Huppert), who is a former associate of Jaffe and Jaffe. She provides the gloom-and-doom side of existential philosophy to balance the positive worldviews of Bernard and Vivian. She plays an important role in facilitating Albert and Tommy’s existential quest. She believes that “betrayal embodies the universal truth”; Albert and Tommy can certainly relate to that because both have experienced bitter betrayal.

Through these wacky characters, who are naturally capable of saying and doing outrageous things, Russell has plenty of latitude to ponder the quandaries of human existence and to explore pathways to meaning and purpose. These far-out characters generate many truly hilarious scenes and much memorable dialogue, making existential psychology easier to swallow.

The Plotline

I Heart Huckabees does not have much of a story. There is no unifying leitmotif, no climax, and no denouement. The film is essentially carried by the characters. The main premise of the film addresses how the different characters struggle with their existential angst with the help of three existential detectives; these lives intersect because they are all connected with Huckabees and with the existential detectives. At the end, some progress has been made in each person’s existential quest, but there are no breakthroughs and no clear resolutions. Life remains a work in progress.

The film opens with Albert reciting a poem as part of his press conference before a small audience of activists and reporters. With his squinted, intense eyes and unkempt long hair, he intones, “This is a rock. Nobody sits like this rock sits. It just sits.” He makes it his mission to protect this large rock, because its simple existence is important for ecology. This is just one of many hilarious scenes. Only a guy with rocks in his head would try to use dumb poetry to protect a rock!

The next interesting scene finds Albert running through a mazelike hallway in search of the office of existential detectives Jaffe and Jaffe. (An image of being lost in life? This is one of the many clever metaphors used by Russell.) Albert wants the detectives to investigate the repeated coincidence of his seeing a tall African man in uniform. Is this a sign of his insecurity and paranoia? He should feel insecure, because Brad has actually planted the business card of Jaffe and Jaffe in Albert’s jacket pocket, and Brad has hired the existential detectives to investigate Albert.

The first existential question from Vivian Jaffe is, “Have you ever transcended space and time?” Albert replies that he is not sure what she means. Bernard Jaffe then shows Albert a blanket, which symbolizes that everything in the universe is interconnected and everything matters. Bernard teaches Albert how to “shut down your everyday perception” by lying inside a dark black bag so that he can meditate and get connected with his inner being; however, only violent images float through Albert’s mind—specifically, images of chopping off the head of his archenemy Brad. In his subsequent exposure to this treatment, Albert’s vision becomes less violent and less chaotic. The black bag treatment reminds us of Buddhist mindfulness training (Brazier, 1998).

Eventually, Brad is able to wrest out the leadership position of the Open Space Coalition from Albert, thus removing the obstacle to Huckabees’ expansion plan, but his own personal life begins to unravel. When Bernard and Vivian probe into Brad’s life, they uncover his serious existential issues. For example, Brad repeatedly tells a phony story about how he is able to get Shania Twain to eat a chicken salad sandwich, which she dislikes intensely. The existential detectives press him about the Shania story. This undermines Brad’s self- confidence and makes him defensive, asking, “How am I not myself?” This is the question Russell would like his audiences to ask themselves after viewing I Heart Huckabees.

Later, when Brad is asked by his colleagues to retell the Shania story during a corporate meeting, he pukes, a visible sign of him being nauseated with his own phoniness. This is the beginning of his fall from grace, and it is followed by more abysmal things in quick succession. First, his house is burned down by Albert. Then, his girlfriend Dawn (Naomi Watts), disillusioned with Brad’s shallow phoniness, leaves him for Tommy, who is attracted to her in spite of her dirty face and homely bonnet and overalls. Perhaps as a result of suffering and pain, Brad becomes aware of his meaningless existence in a lonely universe. The usually self-assured Brad finally breaks down and cries. Caterine takes a picture of Brad crying and gives it to Albert.

Albert sees himself in Brad’s brokenness and sorrow. Showing Brad the photo of him crying, Albert asks, “Who is this, me or you?” At long last, Albert understands his shared humanity with his vanquished foe and the truth about inevitable connections. Albert begins to appreciate the necessity to integrate Caterine’s dark existentialism with the optimism of the Jaffes and wonders whether these three detectives are actually working together.

At this point, Albert has achieved a certain level of enlightenment and reconciliation. Along the way, he has learned a great deal from Caterine, who was introduced to him by Tommy. When Caterine drives Albert and Tommy to Albert’s mother’s apartment, she uncovers some important pieces of information about Albert’s life. The young African man, Steven Nimieri (Ger Duany), is actually a Sudanese refugee who was adopted by a White Christian family, and he works as a doorman in Albert’s mother’s apartment building. Caterine points out that if Albert had been more honest about the so-called coincidental meetings with Steven, he would have learned more from the Jaffes. Caterine also discovers Albert’s pathetic childhood. Albert’s anger and hostility may have originated from his painful childhood memories.

Caterine teaches Albert two more important lessons. She asks Tommy to hit Albert in the face repeatedly with an inflated rubber ball. This is related to a practice in Zen Buddhism (Roshi, 1989). “I am free to just exist,” Albert exclaims, in response to this treatment. The powerful sensation of being here and now sets him free at least momentarily from the burden of his past and his obsessions with his enemies. Caterine also reminds them that they cannot stay in the state of pure being for long and that “it’s inevitable to get drawn back into human drama.” To demonstrate her points, she plays footsy with Albert, gets him sexually aroused, and leads him to the woods, where she pushes his head into a muddy puddle, and he in turn covers Caterine’s legs and face with mud. In their sordid, primitive state, they kiss each other passionately and make love doggy style. This hilarious mud-and- sex scene is another milestone in Albert’s existential quest. He becomes connected with the good earth and another naked human being by abandoning himself. He also learns that he can create moments of joy and intimacy in the midst of a cruel and dark world.

At the end, the two soul mates, Albert and Tommy, return to the rock, which Albert has “saved.” There they sit on the rock and in a relaxed tone talk about inner connections that grow from the excrement of human trouble. All the while, the three existential detectives watch them from a distance.

Tommy: What are you doing tomorrow?

Albert: Thinking of chaining myself to a bulldozer. Wanna come?

Tommy: Sounds good. Should I bring my own chains?

Albert: We always do.

Then, with glee, they begin to hit each other’s faces with the rubber ball.

Lessons of Existential Psychotherapy

The ending sums up the challenges of living authentically: We must live with what we have and do what we can, regardless of our circumstances and feelings. We always have to bring our own chains, which are both our limitations and our powers. We also need someone to hit us in the face just to remind us that self-transcendence must be rooted in reality—the dark, chaotic, absurd reality as described by Sartre (2001). The naive positive psychology of the Jaffes must be married to the realistic pessimism of Caterine in order to create a positive existential psychology that can flourish in difficult times.

Some people might go away from the film feeling that existential psychotherapy disrupts people’s lives and makes them miserable. They feel uncomfortable with the idea of being confronted with disturbing and even impossible questions, such as Who are you? Why are you here? What is the meaning of suffering? Does anything really matter? The power of existential psychotherapy is that no one can be exposed to deep, probing existential questions without undergoing genuine change. Every character in I Heart Huckabees has undergone some sort of personal transformation. Their changes begin from within and manifest themselves in a lasting change of lifestyle. The most dramatic transformation can be seen in Dawn, the face and voice of I Heart Huckabees. She appears to be the typical “dumb blonde” who should be happy to just look pretty, dress pretty, and perform her sexy routines in her commercial spot. But once she becomes disillusioned with her superficial life, she is willing to change, whatever the cost. She begins to dress like a Mennonite woman, in a white bonnet and overalls. Immediately, she is denounced by Brad as “ugly” and replaced by a sexy new model. The lesson: One must be prepared to pay a price for authentic living.

Socrates says that an unexamined life is not worth living. But an examined life is worth all the trouble and suffering. Just as resurrection must be preceded by death, so must rebirth be preceded by the disruption and deconstruction of the old way of life. One needs to step out of the comfort zone and embark on the existential quest in order to experience real-life change. The alternative is to continue the same inauthentic existence, going through life without knowing what life is all about. Every individual must make this fundamental choice—this is the heart of existential therapy.

I wonder whether existential detectives will emerge as one of the helping professions, along with life coaches and counselors. Their methods of spying on their clients and invading their private lives will run into ethical problems, but their premise is correct. In existential therapy, the therapists really need to enter into the world of their clients. At the same time, clients are invited to enter the therapists’ lives, which must be open and genuine. There is no question about the efficacy of their methods; they are able to produce life changes in all their clients, according to I Heart Huckabees.

I have always believed that films are a powerful medium to teach psychological truths because they can touch people’s lives deeply without preaching to them. Russell has done an excellent job in demonstrating several important principles of existential psychotherapy in the context of a comedy. The best way to make psychology a household word is to make good movies. Russell has succeeded in making “existential” a popular term, and his therapeutic rubber ball may even become a popular item in supermarkets.

Russell deserves full credit for his creativity and courage; he has produced a film that no major movie studio would dare to touch, because it does not follow any of the proven, money-making formulas. I have the feeling that I Heart Huckabees will appeal to those who are sick and tired of mindless, special-effect-laden blockbuster movies; it may even attract a cult following who enjoys the ritual of being smacked in the face by a rubber ball in order to feel awakened spiritually.

References

- Brazier, D. (1998). The feeling Buddha: A Buddhist psychology of character, adversity and passion. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roshi, P. K. (1989). The three pillars of Zen: Teaching, practice, and enlightenment (rev. ed.). New York, NY: Anchor Books.

- Sartre, J. P. (2001). Jean-Paul Sartre: Basic writings (S. Priest, Ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2005). The meaning of life according to David Owen Russell: Existential psychotherapy made easy [Review of the film I Heart Huckabees]. PsycCRITIQUES, 50(46). doi:10.1037/05188912

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.