Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness and Flourishing (3rd ed.)

By William C. Compton and Edward Hoffman

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2019. 528 pp.

ISBN 978-1544322926 $95.00

Reviewed by Paul T. P. Wong

Abstract

Compton and Hoffman’s third edition of Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness and Flourishing is commended for advocating an inclusive positive psychology that not only honours the rich humanistic heritage and the major contributions from mainstream psychology, but also recognizes the two emerging trends in PP 2.0. The first is the reality that suffering and vulnerability are the foundation for building a solid existential positive psychology of optimism and flourishing that can endure the inevitable vicissitudes of life. The second trend is the importance of indigenous positive psychology, especially Eastern psychological systems that offer viable insights and a variety of hypotheses about the nature of the self and ultimate happiness.

Introduction

Any book review reflects the reviewer’s own scholarship and perspective. I want to state right at the outset that my view on positive psychology has been shaped by my experience of suffering (see Wong, 2019a), which demands a different kind of positive psychology, generally known as Second Wave Positive Psychology (PP 2.0). Therefore, it is inevitable that in this book review, my focus is on how this textbook is related to the important new developments in PP 2.0, which may represent a more effective way to help the suffering people survive and thrive My hope that this review will help expand the horizon for future PP research and intervention.

The two authors of this textbook have a combined history of 80 years in doing research and teaching in positive mental health and wellbeing. This rich history is clearly reflected in the breadth and depth of their coverage, especially the older humanistic literature and the latest developments in indigenous psychology as well as Second Wave Positive Psychology (PP 2.0).

This new edition has 503 pages. in contrast to its earlier edition which had only 381 pages. With approximately 400 new references and many new topics, this textbook represents the most balanced and comprehensive treatment of the different trends under the umbrella of positive psychology. It covers the traditional topics of Introductory Positive Psychology (Peterson, 2006; Snyder, Lopez & Pedrotti, 2014). What makes Compton & Hoffman (2019) different is that it attempts to integrate research from the humanistic tradition.

“Today, the differences between positive psychology and humanistic psychology are diminishing.” (Compton & Hoffman, 2019, p. 23) I too have emphasized that even the remaining differences in philosophical assumptions will disappear once most positive psychologists accept the necessity of taking a more holistic and integrative approach towards complex human issues (Wong & Roy, 2017).

Contribution to the Positive Psychology of Suffering

Another uniqueness is that Compton & Hoffman (2019) devoted many of the pages to integrate the positive psychology of human suffering. More than a decade ago, Snyder and Lopez (2007) wrote in their textbook on positive psychology:

“Although we explore the positive, we emphasize that this half is no more the entire story than is the negative side. Future psychologists must develop an inclusive approach that examine both the weakness and the strengths of people, as well as the stressors and the resources in the environment. That approach would be the most comprehensive and valid.” (p. 9)

To a large degree, Snyder and Lopez’s (2007) wish has been realized in the present textbook by Compton and Hoffman. Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth’s (2015) produced the first major textbook the explores the ‘dark’ side of life and its important role in our positive functioning and transformation as human beings. Compton & Hoffman (2019) goes one step further by emphasizing the necessity to integrate human suffering as the basis for wellbeing, meaning and resilience.

For example, on page 172, they cited Dunn’s (1961) research that high-level wellness depended on a combination of living a meaningful live and coping with challenging environments. Similarly, after devoting many pages to posttraumatic growth, they cited Kramer’s (2000) research on the wisdom of being open to both positive and negative experiences and grappling with difficult existential life issues, a process that helps transform negative experiences into life-affirming ones (p. 267).

Their coverage of the topic of suffering encompasses Rollo May’s emphasis on existential anxiety and the power of the daimonic, Frankl’s meaning of suffering, Killam’s (2015) review of post-traumatic growth, Cowen and Kilmer’s (2002) article challenging the possibility of obtaining stable wellbeing by neglecting fear and death anxiety, and Kaiser’s (2009) book questioning the desirability of focusing only on strengths.

They also introduce Shmotkin’s (2005) comprehensive model which assumes that “we all encounter a potentially threatening world, our sense of subjective wellbeing is designed partially to help protect us from the impact of anxiety, worry, and fear.” (p. 382) It is worth noting that Shmotkin’s theory was influenced by terror management theory’s postulate that we are affected by our unconscious fear of death.

In spite of the above, positive psychology is by and large ambivalent towards suffering. On the one hand, most official positive psychology websites emphasize that they also care about repairing what is wrong or broken with people, but their research agenda and publications rarely test the possibility that human suffering can be a portal for happiness and strength.

“Does suffering trump happiness?” (Seligman, 2003). By raising this rhetorical question, Seligman is fully aware that people are concerned about suffering. Without directly answering this question, he wrote:

“I am often asked two disturbing and profound questions about the place of happiness in a troubled world. In a world of war and hate and famine, how can I advocate that psychology investigate happiness? Suffering has first call on our sympathy, on our dollars, and on our brainpower. Only when these nightmares are stilled should we turn our attention to happiness.”

However, he does not agree with this conclusion. He believes that just as clinical psychology can make people less unhappy, positive psychology can make people happier, and these are separate endeavours (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). Following this dichotomous view of psychology, their positive clinical psychology (Peterson & Seligman, 2003) or positive psychotherapy (Rashid & Seligman, 2018) focuses on applying their standard strength-enhancing interventions on clinical populations. Thus, in the same paper Seligman (2003) concludes:

“But most of Positive Psychology is for all of us, troubled or untroubled, privileged or in privation, suffering or carefree. The pleasures of a good conversation, the strength of gratitude, the benefits of kindness or wisdom or spirituality or humility, the search for meaning and the antidote to “fidgeting until we die” are the birthrights of us all.”

Thus, Seligman’s answer to human suffering is the focus on what makes us happy, and such one-sided focus will not only repair what is damaged but bring out what is good and right with all people, “suffering or free”. However, this assumption has not gone unchallenged. Through a number of studies, Nick Brown (2019) concluded that there is no conclusive evidence that positive psychology interventions can improve wellbeing.

Similarly, Yakushko (2019) pointed out the potential dangers of focusing on positivity, and the need to recognize the dark site of human existence as a necessary way to enhance wellbeing:

“Specially, positive psychology has been entirely silent about the fact that one of its leading voices, the author of almost all the handbooks of positive psychology, promoter of ideas that hope is all one needs, committed suicide in 2016. Shane Lopez’ suicide remains basically unacknowledged: With an exception of an obscure obituary by his colleague, all other online and printed documents about Lopez refuse to acknowledge that one of the most published and celebrated positive psychologists took his own life.”

“If even the most celebrated and apparently well-adjusted positive psychologists can succumb to depression that leads to suicide, how effective can his ideology of unmitigated positivity be at producing happiness and mental health? How can we believe his philosophy that “all you need is optimism and control over your thoughts”? And how can the public evaluate positive psychologists’ credibility if they are denied basic facts.” (p. 122-123)

In contrast, PP 2.0 may be considered as the positive psychology of suffering; it takes suffering as the starting point or the foundation, and then explores how we can transform suffering into wellbeing and character strengths. According to this integrative view, a focus on curing pathology without tapping into people’s inner resources and best angels—and a focus on positive emotions and traits without addressing people’s inner demons and the dark side of life—are less helpful than the dialectic approach of integrating negatives and positives in achieving optimal wellbeing. Thus, the basic tenet of PP 2.0 is that flourishing can be achieved only through embracing and integrating human suffering as its foundation. This reorientation changes everything from how we do PP research (Wong, 2019

A similar view can also be found in Fowers, Richardson, & Slife (2017). They provided compelling research evidence and case studies to support their dialectical view that the best pathway to flourishing in spite of the everyday limitations and misfortunes is to embrace suffering as an essential part of our journey towards healing and personal growth. They presented their “breathless optimism” as a corrective for the current scholarship on positive psychology.

We shouldn’t glorify suffering, but we need to understand that suffering imbues life with meaning in many ways. It may trigger our search for meaning and meaning making, thus leading us to a different priority and different path. It may increase our compassion for others who suffer. Finally, suffering often occurs in life domains of importance to us:

“How can people thrive, given dependency, the complexity of life human limits, and unavoidable suffering? We have written this book to answer the question. How to flourish remain the theme of positive psychology, but there can be no adequate answer with addressing the question of how to integrate the unavoidable suffering. We show not only it is possible to flourish as imperfect beings, but also that human frailty actually central to living well.” (Fowers et al., p. 3)

This dialectical framework has guided all my research on wellbeing. Examples include the positive psychology of transforming stress to competence and resilience (Wong, Wong, & Scott, 2006); the positive psychology of transforming the terror of death into death acceptance and meaning in life (Wong & Tomer, 2011); the deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity (Wong & Worth, 2017); the positive psychology of transforming despair into tragic optimism (Wong, 2009); and positive aging (Wong, 1989). All these examples illustrate the power of positive interventions based on the dialectical mindset.

At long last, Compton and Hoffman touched on many of the above themes, which were largely ignored by the positive psychology community when the above topics were first introduced as the new frontiers of positive psychology. They also point out that the success of Buddhist psychology has to do with its primary concern of reducing suffering through mindful meditation as the pathway to ultimate happiness (Hanh, 2017). It is worth noting that Christian psychology holds a similar approach of achieving happiness and flourishing through resolving the problem of evils and suffering. For example, Hall, Langer, and McMartin (2010) proposed that suffering can best be understood as a marker of disordered living and can be seen as a means of cultivating characteristics that are essential to flourishing.

Similarly, Frankl (1985) discovered that a meaningful life is based on understanding the meaning of suffering. Peterson’s (2018) concept of a meaningful life is also built on the foundation of suffering. Personally, it has been through my struggles to survive the horrors of Japanese occupation, cancer, betrayal, discrimination, and the Christian faith that I have discovered the power of PP 2.0.

Unfortunately, the concept of finding meaning, strength, and happiness through suffering is still dismissed by leading American positive psychologists. As a case in point, I have been repeatedly told by PP leaders and journal reviewers that my view on suffering is “pessimistic and unscientific” and they demanded empirical evidence to support my claim that life is full of suffering. Do we need empirical evidence from psychology labs to prove that life is full of suffering, when suffering is a universal phenomenon experienced by every human being? Such resistance to suffering hinders positive psychology from exploring the new frontiers of the paradoxical and dialectical mindset as illustrated by Frankl’s concept of tragic optimism (Wong, 2009).

Therefore, it behooves all positive psychologists to ponder the wisdom of Gandhi—“To rejoice in happiness is to invite misery. Real happiness springs from sorrow and suffering”—that is the paradoxical truth of PP 2.0. Authors of the present textbook deserve commendation for having included suffering as a legitimate topic for positive psychology and repeatedly warning against a dogmatic positivist view of doing research only on what is positive and desirable. My only critique is that it did not introduce the Flower et al (2017), although it made several references to Flower’s earlier work.

Contribution to Indigenous Positive Psychology

In the words of Compton and Hoffman (2019):

“Among the frequent criticisms of positive psychology (and Western psychology in general) has been that it over-relies on North American and European research participants. It is indeed clear that some research findings are attributed universal significances when they actually apply only within a specific culture at a specific historical moment.” (p. 391)

They go on to document not only ethnic differences within the West, but also cultural differences between the East and West. Compton and Hoffman (2019) also point out:

“When Eastern psychological systems are understood properly, they offer viable insights on well-being, the nature of emotion, the elements of personality and how to change behavior in positive ways… A variety of hypotheses about the nature of the self and ultimate happiness are available from Eastern psychology, and relatively few psychologists in the West attempt to tap into this valuable resource.” (p. 392)

It is unscientific to dismiss Eastern ideas and Eastern indigenous psychology without giving it serious consideration. In fact, of the main tenets of PP 2.0 is the dialectic principle.

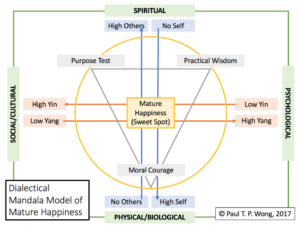

Figure 1. A dialectical model of mature happiness.

From the Asian perspective, everything exists in polarity. The dialectical principle of interaction between yin-yang, as shown in Figure 1 and explained in Wong (2011), is a universal principle underlying all phenomena, including mental health. For example, Lomas and Ivtzan’s (2016) dialectical analysis of wellbeing, Peterson’s (2018) dialectical analysis of meaningful striving through having one foot in security and another foot in order, and Wang, Wong, Yeh, and Wang’s (2018) meaningful life and dialectical coping are all examples of the dialectical approach. The dialogue between PP 2.0 and Buddhism is an example of how to integrate the East with the West (Bliss and Wisdom Global Website, 2017).

Wong’s (2012) dual-systems model crystalizes such diverse phenomena of dialectics as the practical wisdom of navigating an adaptive balance between the dynamic interactions of opposing forces to optimize wellbeing in different contexts. Thus, depending on the situation, one needs to manage the tension of various dialectics, such as getting ahead vs. getting along, trust vs. distrust, engagement vs. disengagement, and happiness vs. sorrow. Such dialectic thinking will contribute to one’s flexibility in adapting to life’s many challenges.

The Future of Positive Psychology

Compton and Hoffman (2019) offer a broad and optimistic vision of a truly balanced, integrative positive psychology:

“Researchers in positive psychology will be kept busy for some time to come exploring personality, lived environments, the interpretation of life events, the various criteria for well-being, and interventions to enhance well-being in an era of new challenges and opportunities for humanity.” (p. 394)

The future of positive psychology seems to lie in two emerging areas of PP 2.0: (a) the integration of negatives and positives and (b) the integration of mainstream and indigenous psychology. Such an integrative positive psychology will open up new opportunities for research and interventions in the global wellbeing movement.

To reinforce their appeal for an integrative positive psychology, the authors of the textbook cite Hefferon, Ashfield, Waters, and Synard (2017):

“We aspire towards more balanced, diverse and inclusive positive psychological research design where one approach is not privileged over the other. We further advocate for researchers to start exploring and engaging in reach across the epistemological spectrum as both quantitative and qualitative approaches can add a piece to the Wellbeing/Flourishing puzzle and have value in their own right.” (p. 217)

Citing Kristjánsson (2010), the authors emphasize that it is difficult to remove values completely from the scientific study of wellbeing. Therefore, researchers who advocate positivist and naturalist values should not automatically dismiss research findings based on transcendental values. Furthermore, they also suggest that positive psychology needs to “specify more precisely what kinds of ideals for well-being or what types of happiness are being pursued through research. None of these issues should negate the scientific enterprise in any way” (Compton & Hoffman, 2019, p. 391).

Ideally, science is the final arbitrator among alternative hypotheses. However, this has to be based on science as broadly defined. Life is complicated, and people are complex. If we believe in the unity of human nature but also that there are different expressions in different cultures, we really need to broaden our approach to research as suggested by the authors:

“Although [science] brings a necessary and welcome addition to the study of well-being, science is a useful tool that may work best when used with other tools that examine the human condition. … The study of individual and group well-being is particularly suited to collaboration among a diversity of scientists, scholars, educators, and other practitioners around the world.” (Compton & Hoffman, 2019, p. 393-394)

Citing Rathunde (2001), they suggest that we go back to William James, John Dewey, and Abraham Maslow. Thus, what was old becomes new again through new theoretical lenses and research methodologies.

For example, PP 2.0 focuses on contributing factors, the dialectical processes of adaptation, and outcome measures of people’s wellbeing and optimism in their darkest hours. It fills a void in existential positive psychology by drawing attention to the suffering masses. PP 2.0 also advocates research needed to measure the interactions between opposing forces and objective indexes of wellbeing in various concrete contexts, from both normal circumstances and aversive situations.

Only empirical research will decide whether in circumstances of adversity, PP 2.0’s interventions to enhance the mature happiness of inner peace through confronting weaknesses, will show a higher level of wellbeing than traditional happiness-enhancing interventions. Research may also decide whether it is more effective to address vulnerabilities and one’s dark side in order to increase one’s character strengths and wellbeing, as advocated by PP 2.0, compared to the single-minded focus on positive emotions and positive traits as advocated by what we can call the “first wave” of positive psychology (PP 1.0). Two books lend support to PP 2.0: Kaplan and Kaiser’s (2013) Fear your strengths: What You are Best at Could Be Your Biggest Problem and Feldman and Kravetz’s (2015) Supersurvivors: The Surprising Link Between Suffering and Success.

A recent study by Kaufman, Yaden, Hyde, and Tsukayama (2019) also supports the value of looking at both positive and negative personality traits in wellbeing. They found that the Light Triad Scale (LTS) predicted satisfaction and a wide range of growth-oriented outcomes, while the Dark Triad was negatively associated with life satisfaction and growth-oriented outcomes. Future research will determine whether the dialectical mindset of accepting the dark side of life is more adaptive than the dichromatic mindset of avoiding it in promoting the mission of “positive, adaptive, healthy and admirable qualities of humanity” in different contexts (Compton & Hoffman, 2019, p. 394).

Conclusion

Compton and Hoffman (2019) end the book with the former mother’s life motto, which in part says:

Throughout the coming years, may you have:

Enough happiness to keep you sweet,

Enough trials to keep you strong,

Enough sorrow to keep you human,

Enough hope to keep you happy,

Enough failure to keep you humble,

Enough success to keep you eager,

Enough friends to give you comfort,

Enough wealth to meet your needs,

Enough faith to banish depression,

Enough determinations to make each day better than yesterday. (pp. 394-395)

This list sounds like a perfect example of the good life from the perspective of PP 2.0—a life of moderation and balance through integrating negative and positive experiences. Such a good life demands the responsibility to do the right thing each day and the discipline to overcome adversities with the spiritual triad of faith, love, and meaning. In short, Compton mother’s life is a demonstration that a good life is achievable only through successfully integrating opposing dialectical forces (Wong, 2011):

“In contrast, Seligman et al. (2005) holds a dichromatic view of positive psychology:

Research findings from positive psychology are intended to supplement, not remotely to replace, what is known about human suffering, weakness, and disorder. The intent is to have a more complete and balanced scientific understanding of the human experience—the peaks, the valleys, and everything in between. We believe that a complete science and a complete practice of psychology would include an understanding of suffering and happiness, as well as their interaction, and validated interventions that both relieve suffering and increase happiness—two separable endeavors.” (Compton & Hoffman, 2019, p. 410)

After 20 years of positive psychology research, the present book shows us that by following the Hegelian dialectical logic, clinical psychology (thesis) and positive psychology (antithesis) are moving into the stage of synthesis as evident in PP 2.0. Thus, suffering and weakness are the very foundation for building a solid existential positive psychology of optimism and flourishing that can endure the inevitable vicissitudes of life. Compton and Hoffman’s (2019) book shows us that the most powerful tool in any psychologist’s toolbox is neither the skill to repair brokenness, nor the skill to increase strength, but the skill to transform brokenness into strength, thus integrating healing with flourishing.

It has been a validating experience for me to read this positive psychology textbook, because the authors happen to share the same orientation towards positive psychology as my own. They not only honour the rich humanistic heritage and the major contributions from mainstream psychology, but also recognize the two emerging trends of PP 2.0, namely, the positive psychology of suffering and indigenous positive psychology. The future of positive psychology is that it will be an essential aspect of training for all mental health professionals, because healing depends on the innate human capacity for meaning, relationships, and faith in transcendental values.

Compton and Hoffman’s sweeping, bold vision of inclusiveness, diversity, and integration for the future of positive psychology show us how we can build a better life for the self and for society by confronting and transforming the dark side of life as the foundation for human flourishing. It was written in a clear and easy to understand style. It also includes a Personal Exploration Section for students to engage with the concepts in a personally meaningful way. That is why I highly recommend Compton and Hoffman’s (2019) book as a textbook for positive psychology.

References

- Bliss and Wisdom Global Website. (2017, October 24). Positive Psychology 2.0 and Dharma—Talk between Dr. Paul T. P. Wong and Bliss & Wisdom Buddhist Sangha community. Bliss and Wisdom Global Website. https://www.blisswisdom.org/events/e/1981-40532

- Brown, N. J. L. (2019). Can positive emotions improve physical health? An examination of some claims from positive psychology (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Groningen, The Netherlands. Retrieved from https://www.rug.nl/research/portal/nl/publications/can-positive-emotions-improve-physical-health(13bec5f4-a63a-46ad-9b07-00067beb0b1c).html

- Compton, W. C., & Hoffman, E. L. (2019). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and flourishing (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cowen, E. L., & Kilmer, R. P. (2002). “Positive psychology”: Some plusses and some open issues. Journal of Community Psychology, 30(4), 449-460. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10014

- Dunn, H. (1961). High-level wellness. Arlington, VA: Beatty.

- Feldman, D. B., & Kravetz, L. D. (2015). Supersurvivors: The surprising link between suffering and success. New York, NY: HarperWave.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Hall, M. E. L., Langer, R., & McMartin, J. (2010). The role of suffering in human flourishing: Contributions from positive psychology, theology, and philosophy. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 38(2), 111-121. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164711003800204

- Hanh, T. N. (2017). How to fight (Mindfulness essentials). Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.

- Hefferon, K., Ashfield, A., Waters, L., & Synard, J. (2017). Understanding optimal human functioning–The ‘call for qual’ in exploring human flourishing and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 211-219. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1225120

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kaiser, R. (Ed.). (2009). The perils of accentuating the positive. Oklahoma City, OK: Hogan.

- Kaplan, R. E., & Kaiser, R. B. (2013). Fear your strengths: What you are best at could be your biggest problem. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Kaufman, S. B., Yaden, D. B., Hyde, E., & Tsukayama, E. (2019). The light vs. dark triad of personality: Contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467

- Killam, K. (2015, December 15). How to find meaning in suffering: Useful insights from research on “post-traumatic growth”. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-to-find-meaning-in-suffering/

- Kramer, D. A. (2000). Wisdom as a classical source of human strength: Conceptualization and empirical inquiry. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 83-101. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.83

- Kristjánsson, K. (2010). Positive psychology, happiness, and virtue: The troublesome conceptual issues. Review of general psychology, 14(4), 296-310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020781

- Lomas, T., & Ivtzan, I. (2016). Second wave positive psychology: Exploring the positive–negative dialectics of wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1753-1768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9668-y

- Peterson, C. (2006). A Primer in Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Character strengths before and after September 11. Psychological Science, 14(4), 381-384. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.24482

- Peterson, J. B. (2018). 12 rules for life: An antidote to chaos. Toronto, ON: Random House Canada.

- Rashid, T., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2018). Positive psychotherapy: Clinician manual. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Rathunde, K. (2001). Toward a psychology of optimal human functioning: What positive psychology can learn from the “experiential turns” of James, Dewey, and Maslow. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 41(1), 135-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167801411008

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Does suffering trump happiness? Authentic Happiness. Retrieved from https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/newsletters/authentichappiness/suffering

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410-421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

- Shmotkin, D. (2005). Happiness in the face of adversity: Reformulating the dynamic and modular bases of subjective well-being. Review of General Psychology, 9(4), 291-325. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.4.291

- Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2007). Positive psychology: The scientific and practical explorations of human strengths. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Snyder, C. R., Lopez, S. J., Pedrotti, J. (2014) Positive Psychology: The Scientific and Practical Explorations of Human Strengths. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Wang, S.-Y., Wong, Y. J., Yeh, K.-H., & Wang, L. (2018). What makes a meaningful life? Examining the effects of interpersonal harmony, dialectical coping, and nonattachment. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 21(3), 198-204. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12212

- Wong, P. T. P. (1989). Personal meaning and successful aging. Canadian Psychology, 30(3), 516-525. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079829

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyány, & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019a). Why and How I Developed the Positive Psychology of Suffering. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/why-and-how-i-developed-the-positive-psychology-of-suffering/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019b). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019c). A Clinical Case Based On Meaning Therapy And PP 2.0. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/a-clinical-case-based-on-meaning-therapy-and-pp-2-0/

- Wong, P. T. P., & Roy, S. (2017). Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology. London, England: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Tomer, A. (2011). Beyond terror and denial: The positive psychology of death acceptance. Death Studies, 35(2), 99-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.535377

- Wong, P. T. P., & Worth, P. (2017). The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity [Special issue]. Psychology and Education, 54(3/4).

- Wong, P. T. P., Wong, L. C. J., & Scott, C. (2006). Beyond stress and coping: The positive psychology of transformation. In P. T. P. Wong, & L. C. J. Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 1-26). New York, NY: Springer.

- Yakushko, O. (2019). Scientific Pollyannaism: From inquisition to positive psychology. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2020). The maturing of positive psychology and the emerging PP 2.0 [Book review of Positive Psychology (3rd ed.) by William Compton and Edward Hoffman]. International Journal on WellBeing, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i1.885