Abstract

Viktor Frankl has the best answer to the mental health crisis during COVID-19, and we ignore him at our own peril. His dialectical and paradoxical self-transcendence (ST) model emphasizes that we can find our true self only by letting go of the old one. He defines meaning in terms of ST and propose that meaning is the key to mental health and flourishing. My remembrance of Frankl revolves on his three aspects of ST: (1) ST is an awe-inspiring way of life, (2) ST is at the heart of therapies, and (3) ST represents a new paradigm for wellbeing research.

Keywords: Viktor Frankl, logotherapy, meaning therapy, self-transcendence, awe, existential positive psychology, suffering, resilience

Looking back, I owe Viktor Frankl such a great debt of gratitude that I do not even know how to start recounting his impact on my life and career in psychology. His writing is like an inexhaustible gold mine; the deeper I dig, the more I discover.

What really connects us is our similar experiences in suffering. Frankl was the product of German occupation, Nazi concentration camps, and discrimination against Jews; and I am the product of Japanese occupation, the Chinese civil war, Hong Kong refugee status, and discrimination against Asians in North America.

It was inevitable that my research on how to reduce suffering led me to Frankl’s classic Man’s Search for Meaning (1946/1985). This why both of us have come to the same conclusion that our best self comes from our worst self and worst circumstances – a heresy to most positive psychologists and most Americans, but a truth consistent with the ancient wisdom of Taoism.

After more than 3 decades of studying Viktor Frankl, my professional judgement is that Dr. Frankl has the best answer to the mental health crisis during COVID-19 and we ignore him only at our own peril. Most people merely recognize him for his bestseller Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl, 1946/1985), but very few understand his wisdom that we can find our true self only by letting go the old one. His dialectical and paradoxical self-transcendence model reminds us of Taoism.

In a nutshell, his self-transcendence model of mental health has two parts. First, his optimistic worldview in human potential (responsible freedom, the will to meaning, and the intrinsic meaning of life) transcends his tragic worldview of life (death, pain, and guilt); this mixture of positive and negative beliefs results in the invincible Tragic Optimism, which enables us to dream the impossible dreams (Frankl, 1985; Leung et al., in press). His central concept, “the will to meaning”, is a spiritual act of volition to direct one’s life toward a transcendental goal in order to rise above the evitable suffering and death (Frankl, 1988).

Second, his meaning triad (creative, experiential, and attitudinal values) transcends the neurotic triad (aggression, addiction, and depression), resulting in meaningful living in spite of the potential for mental illness in a cruel and meaningless world. In other words, it is impossible to have meaning and happiness without death and suffering just as we cannot have light without darkness. Thus, his Yin-Yang framework of self-transcendence is the key to mental health and flourishing (Wong, 2021a).

I did not discover the essence of Frankl’s logotherapy by chance; it is the result of more than three decades of engagement with Frankl’s work. In my remembrance of Frankl, I just want to I highlight three aspects of self-transcendence: (1) It is a lifestyle of a soul set on fire; (2) it is the heart of all effective therapeutic modalities; and (3) it is the ground-breaking insight into flourishing based on self-transcendence.

Self-Transcendence is an Awe-Inspiring Way of Life

In 1996, when I was working on my first edited volume of The Human Quest for Meaning (Wong & Fry, 1998), I took a chance and made a cold call to Viktor Frankl in Vienna. I did not expect to get any answer because he was an international “Rockstar” with his Man’s Search for Meaning (1946/1985), which sold over 16 million copies globally. To my surprise, he returned my phone call almost immediately with a strong voice. He apologized that he was too old to contribute a forward to my book and suggested a number of prominent logotherapists; all of them eventually contributed to my book.

He listened with great interest to my meaning research and my integrative meaning therapy; but what impressed me most was his passion for spreading the message that people cannot become fully human without discovering their transcending self and dedication to serve the greater good.

Later that year I was able to present my paper on meaning therapy during the 1st Congress of the World Council for psychotherapy (WCP), which took place in 1996, Vienna. I hoped to meet him in person, but for some unexpected personal reason, I was not able to attend the Conversation Hour with Viktor Frankl. However, my wife and I were able to visit his resident at Mariannegasse 1, 8th District, Vienna.

From my brief encounter with Frankl over the telephone, I could sense his unwavering passion to restore the soul in psychology (Wong, 2021b), just one year before his death. From my personal experience as an 84-year-old man, I know that it must have been exhausting for a 91-year-old Frankl to talk to me over the barriers of distance and different accents for more than half an hour. I was awe-struck and deeply loved by a soul on fire for logotherapy.

From my reading of his writing, and from my interaction with him, it is abundantly clear to me that according to Frankl, self-transcendence is neither a unique positive emotion to be pursued (Keltner & Haidt, 2003), nor a conceptual form to be expanded (Reed, 2003). It is basically a spiritual awakening that moves one’s heart and soul so deeply that leading to the reorientation of one’s life purpose and a fundamental change in one’s life (Wong, 2016a, 2017a).

More specifically, Frankl believed that self-transcendence is a primary motivation characterized by (a) a shift in focus from the self to others, (b) a shift in values from extrinsic motivation, such as materialism, to intrinsic motivation (the activity itself is the reward), (c) an increase in moral concern of doing what is right, and (d) the emotion of awe that contributes to life transformation and which inspires others (Wong, 2017b). My recent research on the four-factor measurement of self-transcendence (Wong, Arslan et al., in press) shows that a re-orientation of focus and value remains the dominant factor after several factorial studies, but the emotion of awe did not emerge as a unique factor.

Recent self-transcendence research tends to focus on the emotion of awe experienced during cognitive accommodation of something vast and unusual (Keltner & Haidt, 2003) without any reference to Frankl and his ST perspective of awe (Allen, 2018).

For Frankl, awe is not just an emotional response due to something so spectacular that it cannot be assimilated by our existing belief and knowledge structures. It is more like the following quotes from Anagarika Govinda: “The feeling of awe and sense of wonder arises from the recognition of the deep mystery that surrounds us everywhere, and this feeling deepens as our knowledge grows.”

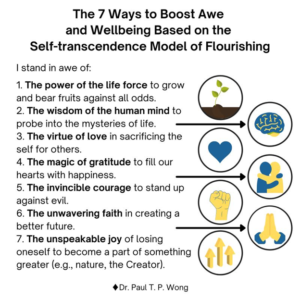

In other words, Frankl’s self-transcendence model provides a much broader and deeper way to experience awe as a lifestyle, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The Seven Ways to Boost Awe and Wellbeing Based on the Self-Transcendence Model of Flourishing

The above figure shows that a self-transcendent life naturally involves two kinds of emotion of awe. The first kind of awe comes from our appreciation of all small wonders and deep mystery of everyday life even in mundane circumstances – a baby in her mother’s arm, a tiny wildflower in a rock, or the smile of a wrinkled and toothless old man. This emotion of awe involves a mixture of feelings when marvelling at human resilience, and a deep sadness toward suffering and death; this calm-based awe is like the sparkling still water that runs deep with dark undercurrents.

The second kind of awe arises from our encounters with something so spectacular, not only the vastness and beauty in nature that it takes our breaths way and transports us to a transcendental realm, but also in moral excellence or sacredness that moves our heart and soul deeply that it evokes emulation (Kristjánsson, 2017).

There is already some evidence that meaning is involved in dispositional awe (Zhao et al., 2019), which can be better understood as the kind of awe as an inseparable aspect of living a meaningful or self-transcendental life. The neural basis of dispositional awe (Guan et al., 2019) supports Frankl’s broader perspective of awe; he was awe-struck by both the beautiful sunset and remarkable kindness and courage shown in some inmates which enlarged his heart and soul rather than his mind.

Self-transcendence is at the Heart of all Therapies

Frankl (1949/1986) considered logotherapy as an adjunct to all modalities of psychotherapy and as a medical ministry to medical practice because how to cope with suffering and death is a timeless and universal existential theme. In other words, how to transcend suffering and death is a transdiagnostic approach to health. That is why I have argued that integrative meaning therapy represents the future of psychotherapy (Wong, 2020a).

Joseph Fabry (Wikipedia, 2021) carried on the mission of Frankl in North America as founder of the Institute of Logotherapy in Berkeley, California (Noetic Films, 2020). He became my mentor in logotherapy. In July 1995, I sent him the first draft of my chapter on Meaning-centered therapy (Wong, 1998a); and he replied immediately and wrote: “I read it with mounting enthusiasm and relish every page.”

This letter began a 3-year friendship and mentorship through exchange of letters and phone calls. During this period, he shared with me what Frankl believed deeply and what caused the fragmentation in the logotherapy movement. My publications in the Forum for Logotherapy (Wong, 1997, 1998b, 1999) reflects his mentorship.

The highlight of this relationship was my visit to his home near Berkeley in August 1998 (see Figure 2). Over the dinner table and a long walk after dinner, we discussed a wide range of things related to the future of logotherapy. He was excited about me organizing the Festival of Meaning in Toronto and editing a special issue of the Forum of Logotherapy, focusing on meaning research. He assured me that Dr. Barnes, the person appointed by him as the President of Institute of Logotherapy in Texas, would not object to his suggestion.

Figure 2

Meeting Between Joseph Fabry and Paul Wong in August 1998

Unbeknownst to him, his enthusiasm in promoting me to Dr. Barnes turned out to my downfall after his death. In May 1999, shortly after his death, I was expelled from the Institute of Logotherapy by Dr. Barnes on some trumped-up charges (Wong, 2017c). This misfortune turned out to be a blessing in disguise because it gave me the free hand to develop integrative meaning therapy (Wong, 2009a, 2016a, 2016b) and launch the International Network on Personal Meaning (www.meaning.ca) which organizes Biennial International Meaning Conferences and founded the International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology (IJEPP). I believe that Frankl would be pleased that I did not disappoint him by becoming an international ambassador for logotherapy (my two encyclopedia entries).

Self-Transcendence Represents a New Paradigm of Wellbeing Research

“Only to the extent that someone is living out this self transcendence of human existence, is he truly human or does he become his true self. He becomes so, not be concerning himself with his self’s actualization, but by forgetting himself and giving himself, overlooking himself and focusing outward.” – Viktor E. Frankl

Frankl’s greatest contribution to wellbeing research was his discovery that self-transcendence is the most promising path for us to become our best true self through overcoming all internal and external obstacles and all the destructive forces.

This represents a paradigm shift which simultaneously restored the human soul and spirituality to the center stage of psychology and elevated the search for meaning as the most important primary motivation capable of healing the broken hearted, the wounded ego, and empowering human beings to flourish in the face of suffering and death.

In one bold stroke, Frankl succeeded in integrating the best wisdom from the East and the West, and clinical psychology with positive psychology. Thus, Frankl, along with William James and Abraham Maslow, deserve the credit as the grandparents of existential positive psychology—an emerging wave for the 21st century.

To both Frankl and Maslow, self-transcendence represents the highest values. Maslow (1971) has provided a comprehensive definition:

“Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos.” (p. 269).

The main difference is that Maslow began with self-actualization and discovered in his old age that self-actualization could be realized without moving to the highest stage of self-transcendence. In contrast, due to his more difficult circumstances, Frankl advocated that we need to begin with self-transcendence at our life goal, and self-actualization and happiness will ensue as a result.

In addition, Frankl has successfully resolved several existential issues. For example, for the ontological dilemma of staying the same vs. making changes for a better future, Frankl argues for taking the risk of moving forward with the risks of uncertainly and possible failure because life is not about maintaining the status quo or homeostasis, but about embracing the necessary tension and risks of growing. It is the process of striving that makes us fully alive. His logic is that human beings are an open system in a complex evolving society, where the only constant is change. That is why we need to have the courage to embrace change in order to move forward. It is consistent with the Chinese saying: when we paddle upstream, not moving forward is going backward. Progress always involves a struggle and overcoming risks and setbacks.

Based on Frankl’s teaching and my own lifelong research (Wong, 2019b), the following summarizes the main three insights of existential positive psychology (PP 2.0):

- True positivity is the ability to see the light in the darkness. Cultivating the resilient mindset (Wong, 2020) and the attitude of tragic optimism (Leung, 2019; Wong, 2001) allows one to see the bright side of the worst situation and suffering as a blessing in disguise (Jans-Beken & Wong, 2019). This ability needs to be awakened and stretched. Such effort is worth it because it results in sustainable positive mental health even during the worst circumstances.

- True success is to embrace the dark side and turn it into the foundation for achieving one’s highest value. The next step is to strive towards one’s dream made up of one’s highest ideals. This will involve coping with the difficulties and failures by developing the necessary resources according the deep and wide hypothesis (Wong & Worth, 2017) following the resource-congruence model of effective coping (Wong et al., 2006). With problems that are beyond human control, the most congruent ways of coping are religious coping and meaning-focused coping.

- The good life is a balancing act of navigating between opposite forces in each situation. This would require practicing the dual-system model (Wong, 2012) or the Yin-Yang dialectic to maintain a dynamic balance between two opposite forces. Sustainable mature happiness can be achieved through the practical wisdom and the successful managing of the opponent process of Yin-Yang (Wong, 2021a; Wong & Bowers, 2018).

In terms of application, the following 12 rules for mental heath and flourishing are based on Frankl’s 4 Triads and his deep insight into human nature. To the extent that his timeless classic appeals to all people, Frankl’s rules may be the most promising way to achieving healing and flourishing relative to any other bundle of 12 rules, such as Peterson’s 12 rules for life (2018):

- We all have the freedom and responsibility for our life and wellbeing.

- We all have the free will to pursue meaning rather than power or pleasure.

- Life has intrinsic value and meaning because of its potential to grow and bear fruits.

- Pain and suffering are an inevitable part of life.

- All life ends in death.

- We all feel guilty for our wrongdoings and broken relationships.

- People often react to pain or frustration with aggression.

- People often react to suffering with addiction.

- Depression often results from people’s inability to cope with harsh reality.

- I can face the terrors of life with courage and faith.

- I can create something of value for the greater good.

- I appreciate my life and feel grateful for all the things that has happened to me.

Conclusion

Viktor Frankl, one of the most influential and enduring psychotherapists, continues to speak to the 21st century. His paradoxical wisdom on suffering provides the foundation for PP 2.0 (Wong, 2009a, 2011, 2019). In a time of deadly pandemic, denial or avoidance is no longer an option. The new science of flourishing through embracing what we fear may be the most promising way to save a society riddled with the problems of addiction, suicide, and injustice (Williamson, 2020; Wong, Mayer et al., in press). We still have a lot of work ahead of us in implementing Frankl’s grand vision.

I have presented existential positive psychology for years without getting much attention from the psychological establishment (Wong 2019, 2020c, 2021). Even my recent free book on the Frankl cure (Wong, 2020b) has not received wide attention. This failure may be due to my own inadequacy or discrimination (2020d).

However, my recent invitation to Harvard’s Human Flourishing program to do collaborative research on the new science of flourishing through self-transcendence provides the much-needed confirmation that this new approach to wellbeing research will become mainstream. Following Frankl’s example, I will use my last breath to shout from the roof top:

Fear not and lift up your eyes!

It may be your darkest hour,

your most painful moment,

but a new dawn is near if you don’t give up.

Yes, you can turn suffering into blessing,

if you keep on believing.

References

- Allen, S. (2018). The science of Awe. Greater Good Science Center. https://ggsc.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/GGSC-JTF_White_Paper-Awe_FINAL.pdf

- Frankl, V. (1949/1986). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy. Second Vintage Books.

- Frankl, V. E. (1946/1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1988). The Will To Meaning. Penguin Group.

- Guan, F., Xiang, Y., Chen, O., Wang, W., & Chen, J. (2018). Neural Basis of Dispositional Awe. Frontiers, 12, Doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00209

- Jans-Beken, L., & Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Development and preliminary validation of the Existential Gratitude Scale (EGS). Counselling Psychology Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1656054

- Keltner, D. J., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297

- Kristjánsson, K. (2017). Emotions targeting moral exemplarity: making sense of the logical geography of admiration, emulation and elevation. Theory Res. Educ. 15, 20–37. Doi: 10.1177/1477878517695679

- Leung, M. M. (2019). Tragic optimism: An integrative meaning-centred approach to trauma treatment. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1633497

- Leung, M. M., Arslan, G., & Wong, P. T. P. (in press). Tragic Optimism as a Buffer against COVID-19 Suffering and the Psychometric Properties of a Brief Version of the Life Attitudes Scale (LAS-B).

- Maslow, A. (1971). Farther reaches of human nature. McGraw-Hill.

- Noetic Films. (2020, July 21). MEANING CENTERED PSYCHOTHERAPY – Joseph Fabry 1980. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JljDt29PD5I

- Peterson, J. B. (2018). 12 Rules for Life: An antidote to chaos. Vintage Canada.

- Reed, P. (2003). A nursing theory of self-transcendence. (pp. 145-166). In M. J. Smith & P. Liehr (Eds.), Middle range theory for advanced practice nursing.

- (2021). Joseph Fabry. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Fabry

- Williamson, M. (2020). The origins of America’s mental health crisis. https://www.newsweek.com/marianne-williamson-origins-americas-mental-health-crisis-opinion-1539782

- Wong, P. T. P. (1997). Meaning-centered counseling: A cognitive-behavioral approach to logotherapy. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 20(2), 85-94.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998a). Meaning-centered counselling. In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 395–435). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998b). The endurance of logotherapy. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 21(1).

- Wong, P. T. P. (1999). Towards an integrative model of meaning-centered counseling and therapy. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 22(1), 47-55.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2001). Logotherapy. International Network on Personal Meaning. http://www.meaning.ca/archives/archive/art_logotherapy_P_Wong.htm

- Wong, P. T. P. (2006). Existential and humanistic theories. In J. C. Thomas & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of personality and psychopathology.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009a). Existential positive psychology. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 361-368). Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009b). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511\

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Meaning-seeking, self-transcendence, and well-being. In A. Batthyany (Ed.), Logotherapy and existential analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute (Vol. 1; pp. 311-322). Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017a). From Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy to the four defining characteristics of self-transcendence. com. http://www.drpaulwong.com/four-defining-characteristics-self-transcendence/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017b). Logotherapy. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 1984). Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017c). The untold story of the INPM (Autobiography, Ch. 24). com. http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-untold-story-of-the-inpm/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020a). Existential Positive Psychology and Integrative Meaning Therapy. International Review of Psychiatry. Doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 According to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020c). The maturing of positive psychology and the emerging PP 2.0 [Book review of Positive Psychology (3rd ed.) by William Compton and Edward Hoffman]. International Journal on WellBeing, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i1.885

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020d, September 24). The Unheard Cry of a Successful Asian Psychologist. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2020.1820430

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021a). Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) and global wellbeing: Why it is Necessary During the Age of COVID-19. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 10(1), 1-16.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021b). Preface: Frankl’s cure for a soulless psychology and a sick society. In N. Krasovska & C.-H. Mayer, Psychobiography of Viktor Frankl. Springer publishing.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). IGI Global.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Fry, P. S. (Eds.). (1998). The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications. Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Worth, P. (2017). The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity [Special issue]. Psychology and Education, 54(3/4). http://www.psychologyandeducation.net/pae/category/volume-54-no-3-4-2017/

- Wong, P. T. P., Arslan, G., Bowers, V. L., Peacock, E. J., Kjell, O. N. E., Ivtzan, I., & Lomas, T. (In press). Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the self-transcendence measure-B.

- Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., Arslan, G. (Eds.). (in press). COVID-19 and existential positive psychology (PP2.0): The new science of self-transcendence.

- Zhao, H., Zhang, H., Xu, Y., He, W., & Lu, J. (2019). Why Are People High in Dispositional Awe Happier? The Roles of Meaning in Life and Materialism. Frontiers, 10, 1208. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01208

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2021). The Frankl cure for the 21st century: Why self-transcendence is the key to mental health and flourishing. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 41(2), 33-50. Doi: 10.31234/osf.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.