This is the conclusion chapter for Dr. Paul Wong’s e-book Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective coping with COVID-19 according to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong (2020).

The whole world has turned upside down. The life we used to know has largely disappeared with all kinds of new rules (such as lockdown measures, social distancing) imposed on us in our battle against COVID-19. We can no longer expect that tomorrow will be similar to today because the situation is so fluid–the other shoe may drop at any time–and all of us could get infected. Even the top medical scientists have issued numerous warnings of a second wave.

The whole world has turned upside down. The life we used to know has largely disappeared with all kinds of new rules (such as lockdown measures, social distancing) imposed on us in our battle against COVID-19. We can no longer expect that tomorrow will be similar to today because the situation is so fluid–the other shoe may drop at any time–and all of us could get infected. Even the top medical scientists have issued numerous warnings of a second wave.

With the collapse of traditional values, the surge of social upheavals, endless political tumults, and the 4th industrial revolution, the world is undergoing seismic changes. We have lost our moral mooring and direction in a new world which we don’t really understand.

Indeed, we are going through a global crisis of biblical proportions. The pandemic has exposed the fault lines of our democracy and the discontent of our materialistic way of life. It may be a time for awakening and fundamental change and a new science of suffering as we battle an invisible and ubiquitous deadly enemy.

This book has provided helpful resources on the resilience revolution such as the double helix of self-distancing and self-transcendence, Frankl’s vaccine against suffering, and Wong’s resilience mindset as the front line psychological defence against the pandemic. In this concluding chapter, I want to focus on the need to change ourselves in order to find mature happiness based on inner peace and life balance.

Most people do not fully understand what Frankl meant when he spoke of the need to “change ourselves”. Surely, it means more than mere positive thinking or behaviour modification. The deeper meaning of change can be found in the Greek word repentance (μετάνοια), which means a complete change of mind and heart after self reflection, repudiation of what is wrong, and transforming oneself into something new.

For example, Frankl challenged us to re-orient our life from horizontal living to vertical living in a spiritual/transcendental reality. Don’t you think that this change will make your life deeper and more meaningful? What if there is God, a Supermeaning, or Supreme Master, to whom you will be held accountable? Don’t you think that faith in God will help you to be more responsible in your use of freedom?

Another example: Frankl also challenged us to change our mindset from fear of suffering to embracing suffering. What will happen if you let go your old beliefs and attitudes, and consider the new possibility that suffering may be good for you? It will as least reduce your anxiety level and prompt you to seek the meaning and benefit of suffering, such as placing yourself in harm’s way as a frontline worker or rebuilding your shattered business.

What is Inner Peace? How is it Related to Happiness?

According to Thich Nhat Hanh (2014), the secret to happiness is seeking peace, not excitement; to transform suffering, not running away from it. We need to learn how to face, accept, and embrace our suffering with mindfulness and equanimity. Then we can experience true joy or mature happiness in the midst of adversity.

According to Thich Nhat Hanh (2014), the secret to happiness is seeking peace, not excitement; to transform suffering, not running away from it. We need to learn how to face, accept, and embrace our suffering with mindfulness and equanimity. Then we can experience true joy or mature happiness in the midst of adversity.

This kind of inner peace does not necessarily mean the complete absence of negative thoughts or stress, it does not mean that you need to live a cloistered life of a monk or priest. It simply means a positive state of mind characterized by equanimity, confidence, harmony, and contentment. The good news is that peace could be experienced in every step of the way as you go about your daily business (Thich Nhat Hanh, 1992).

According to Wong & Bowers (2018), “Mature or noetic happiness is characterized by a sense of acceptance, inner serenity, harmony, contentment, and being at peace with self, others, and the world.” It is called mature, because it takes a certain level of personal maturity and spiritual discipline in order to achieve a high level of life satisfaction, even when one could barely maintain a low or modest level of positivity while going through unrelenting trials and tribulations. Therefore, it implies a deep-rooted peace and joy overlaid with fresh wounds, bruises, and stresses that come from daily struggles.

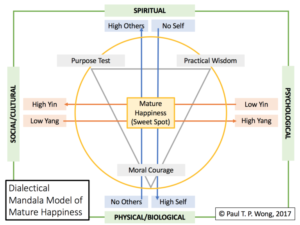

I used a mandala model (see figure 1) to describe this calm-based happiness, which depends on the dialectical interactions between yin-yang and self-others. The model allows an individual to benefit from both the self and others simultaneously, as in the case of self-transcendence. The self and others are viewed as two sides of the same coin, or two separate but interdependent dimensions. Similarly, the model also allows an individual to be both high in yin and yang, as in the case of accepting the bleak reality yet continuing to struggle towards one’s ideals.

Figure 1.

Dialectical Mandala Model of Mature Happiness

This mature happiness requires our ability to navigate dialectical interactions and maintain an optimal balance between the self and others, along with yin and yang tendencies, depending on the specific demand of each context. This ability of agility and flexibility can be strengthened through self-cultivation or practice of the resilient mindset described earlier.

According to this mandala model, the sweet spot of optimal balance and harmony between opposing forces is mature happiness (安樂/安康)—an authentic, spiritual, and enduring happiness that can be sustained amid suffering (Dambrun & Ricard, 2011; Delle Fave et al., 2016; Wong & Bowers, 2018).

Mature happiness encompasses psychological wellbeing (Ryff, 1989) and eudemonic wellbeing (Ryan et al., 2008; Waterman, 1993); it is an attunement-based happiness (Haybron, 2013). According to Wong (2014), “attunement is a positive mental state, characterized by a sense of contentment with life and being at peace with oneself and the world.” In addition, it can even function within the noxious world of pandemic and suffering.

Thus, it demands more than a few positive psychology exercises to achieve inner peace. One needs to develop the skills, attitudes, and habits of living a life of harmony and balance in a dangerous and unpredictable world. This is the concept of the good life according to PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011).

How to Live a Life of Balance and Harmony

The notion of life balance and harmony can be traced back to ancient China, as represented by the principle of Yin-Yang dialectics, believed to encompass everything in nature and responsible for physical and mental health according to Confucianism, Dao/Taoism and Buddhism (Laozi, 2016; Wong, 2016).

The notion of life balance and harmony can be traced back to ancient China, as represented by the principle of Yin-Yang dialectics, believed to encompass everything in nature and responsible for physical and mental health according to Confucianism, Dao/Taoism and Buddhism (Laozi, 2016; Wong, 2016).

Inner peace, harmony, and balance are closely related concepts as indicated by this definition. “Harmony is usually identified as a human value, referring to compatibility and accord in feelings, actions, relationships, opinions, interests, etc. It denotes a state of balance among forces influencing and even opposing one another.” (Chen, 2008, p. 464)

Life is a balancing act because life is full of paradoxes, dilemmas, absurdities, and contradictions. Living well is all about knowing how to balance conflicting forces, values, attitudes, ideas, and emotions and making the right choices that will increase life balance and wellbeing. Here are some common examples of duality:

- The real self vs. the ideal self

- Confessing our past shameful deeds vs. building more mental defences

- Personal freedom vs. public safety

- Individual rights vs. social justice

- Getting ahead vs. getting along

The inability to resolve any of the above conflicts can contribute to a person’s adjustment problems. Our ability to balance the endless conflicting demands in our daily lives is the key to stress reduction and positive mental health (The editors of TIME, 2019).

The inability to resolve any of the above conflicts can contribute to a person’s adjustment problems. Our ability to balance the endless conflicting demands in our daily lives is the key to stress reduction and positive mental health (The editors of TIME, 2019).

Research has shown that harmony or balance is associated with happiness, subjective wellbeing (SWB), and meaning in life (Chen, 2008; Gruman, et al, 2018; Wong, 2012). Research has also shown that there is a symbiotic relationship between inner peace and happiness, and both concepts are associated with positive emotions (e.g., Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

If we still cling to our old patterns of expectations, we would be creating more stress and anxiety to ourselves according to the meaning-maintenance model (Heine et al., 2006). If we want inner peace, we can no longer cling to the old patterns of expectations, such as “hard work will lead to success”, and “good people will be rewarded, while bad people will be punished”. Such expectations are part of the “just world belief”, which will be violated again and again in a chaotic and unjust world.

By the same token, we can no longer only cling to the importance of cognitive consistency (Cartwright & Harary, 1956; Heider, 1946), even though by nature we prefer to see a world that function consistently in an orderly manner that we can predict or control. The new science of existential psychology predicts that the our ability to tolerate and adapt to cognitive dissonance may be more conducive to wellbeing during times of complexity and chaos.

All of us experience the discomfort of cognitive dissonance (CD) from conflicting values or the gap between ideal self and real self, resulting in positive change. However, the new science of PP 2.0 suggests that holding two opposing ideas or emotions can be good for you, even though CD is uncomfortable or stressful. Tolerating CD could increase your cognitive and emotional maturity in the following seven ways:

- It makes you more inclusive regarding diversity.

- It increase your emotional diversity (Ponti, 2017).

- It makes you wiser by discovering that truth is somewhere in the middle of opposing positions.

- It increases your tolerance of people who oppose you.

- It increases your emotional agility (David, 2016).

- It increases your creativity (Leung, 2018).

- It restores your inner peace by living with CD.

Science still lags behind the wisdom of living with dissonance. Consider the following two quotes from F. Scott Fitzgerald and Carl Sagan. Do they resonant with you?

Interestingly enough, some research suggests that listening to Mozart may increase your emotional and cognitive maturity in trying to balance two conflicting beliefs (Jacobs, 2017). Finally, the ability to maintain peace and harmony in a polarized and rapidly changing world may be important for human survival and flourishing.

According to Faabio & Tsusa (2018), the psychology of harmony represents a new area of the positive psychology of sustainable development in the post-modern world. The ability to embrace change, the cognitive flexibility to switch between different coping strategies, and the emotional agility to react to change with positive emotions can all contribute to intrapersonal and interpersonal peace and harmony.

A Profile of Inner Peace

It is always refreshing to see someone who is able to maintain her composure and quiet confidence, even when she is insulted. Threatened, and provoked. You wonder: How could she be so calm even in such desperate situations.

You can see in her eyes that she knows what is going on and that she is on top of the situation. She does not show much emotion, does not readily express her views, and refuses to be drawn into useless arguments. She never responds immediately to unreasonable demands. After some consideration, she would say a very few carefully chosen words that would produce her intended effects.

She can go from crisis to crisis without losing her cool. You wonder: How did she develop her mental toughness, confidence, and competence in making the right decision? Surely, it takes more than yoga or positive psychology exercises to develop such rock-solid leadership qualities and fluid flexibility like water.

Her patience and self-control come largely from a long-suffering heart capable of tolerating all kinds of stupidity and absurdity without losing her composure. She always carries herself with impeccable manners and sense of understated dignity, but her presence calls for respect.

In the midst of many powerful push and pull forces, she is able to maintain her ground and stay calm under pressure. This gives her the advantage over her adversaries because she is able to think with clarity and make wise decision without acting on impulse or habit.

She becomes such a heroic figure because she has learned that life is a balancing act. She knows how to achieve a sense of balance in all areas of life and how to develop a harmonious working relationship with all kind of people, including those she does not like. To become such a well-rounded mature person, she also practices the strategies in the following section.

Strategies to Achieve Life Harmony

Here are 12 strategies that can build your mental muscles to take on all the dirty, vile events that come your way without losing your balance and serenity:

- Know the difference between right and wrong and always do what is right according to your conscience and universal values such as compassion and justice. This will give you a solid moral grounding.

- Know the difference between personal interest and the common good. Always willingly surrender your self-interest for the greater good. This is the practice of self-transcendence and servant-leadership.

- Know your vulnerabilities and what upsets you most. To acknowledge your weaknesses is the best way to protect and improve yourself. Your problem will persist until you dare to face it and learn from it.

- Believe that you can turn every setback to your advantage and accomplish your goal eventually, even though the situation may look hopeless. “As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good.” (English Standard Version Bible, 2001, Genesis 50:20) Therefore, you can celebrate your failures and your fate, because they prepare you for eventual success if you stay true to the course.

- Keep your stillness rituals daily, such as meditation, prayer, tai chi, or spending time with nature. Do them consistently. It is the time to experience solitude and quietness, and to clear your mind of the endless noise while recharging your mental battery.

- Train your mind to focus on one thing at a time, so that you don’t get distracted easily. Your ability to focus will prevent you from being drawn into ruminating over troublesome issues or worrying about negative outcomes.

- Develop the practical wisdom and cognitive flexibility so that you will be able to balance work with play, self-care with caring for others. You also need to have the practical wisdom knowing when to get engage, when to dis-engage, when to advance, and when to retreat. Life is a balancing act.

- Refuse to waste your time on toxic people and refuse to allow them to rob

you of your inner peace. Stay away from them if you can.

you of your inner peace. Stay away from them if you can. - Stop chasing after happiness; instead, learn to maintain a positive mental state of deep joy and serenity in spite of the constant presence of stress in your daily battle with various challenges. In other words, you neither seek excitement with high intensity and positivity, nor do you seek homeostasis.

- Learn to live with paradoxes and cognitive dissonance so you could find a creative solution more easily . It is actually good to have some level of tension and keep the fire in your belly to improve yourself and overcome your problems.

- Learn to remain hopeful, even when you face repeated rejection or failures, by believing in the intrinsic value of your work and believing in eventual vindication.

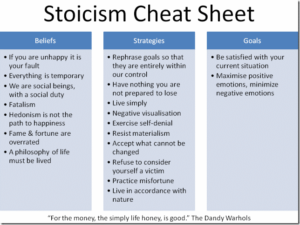

- Think negatively and prepare for the worse so that you can take measures to prevent it from happening and you will not be shocked even when it does happen. This pre-mortem technique was designed by psychologist Gary Klein (2007). His great idea comes from the Stoic tradition (see figure 2).

Figure 2

Ideas from Stoicism

Conclusion

At the heart of inner peace is one’s ability to (a) maintain an optimal balance between opposing forces in any context, (b) live in harmony with the self, others, nature and the supernatural through attunement (Wong, 2014), (c) achieve genuineness or authenticity so that one’s values, thoughts, words, and deeds are congruent with each other, in spite of the pressure of fear and temptations, and (d) develop the ability to tolerate and embrace uncertainty, disconfirmation of expectancies, ambivalent emotions and cognitive dissonance. All of these traits are predicated on living in a hostile world full of suffering and evil.

At the heart of inner peace is one’s ability to (a) maintain an optimal balance between opposing forces in any context, (b) live in harmony with the self, others, nature and the supernatural through attunement (Wong, 2014), (c) achieve genuineness or authenticity so that one’s values, thoughts, words, and deeds are congruent with each other, in spite of the pressure of fear and temptations, and (d) develop the ability to tolerate and embrace uncertainty, disconfirmation of expectancies, ambivalent emotions and cognitive dissonance. All of these traits are predicated on living in a hostile world full of suffering and evil.

In the final analysis, we can sum it all up with the following idiom: no pain, no gain. The positive psychology of suffering (PP2.0) may be the most exciting development in wellbeing research, because we really need to go through the gates of suffering to become better people and become what were meant to be. For example, is better for us to get used to the idea of living with the inevitable prospect of suffering and death in order to gain mental toughness and wisdom.

The valuable source of inner peace can only be earned by going through the steps of confronting, accepting and embracing suffering; similarly, life balance and harmony can be achieved only by learning dialectical (Lomas, 2016) or the dual-system process (Wong, 2012). Even when we want to live a meaningful life, we still need to maintain a proper balance between difference sources of meaning, such as achievement needed to be balanced by acceptance of self-limitations (Wong, 1998). When we learn to embrace and dance with death as a partner for living well, then will be free from all anxiety and fears.

Yes, life can be a beautiful painting with harmony between light and shade, bright and dark colours. Life can also be a beautiful piece of music with different notes in perfect harmony. You can build a new life of peace, balance, and harmony out of shattered dreams and broken relationships by practicing the new concepts, strategies, and skills as outlined in this book.

My colleagues and I are in the process of establishing a new Research Institute of Suffering and Flourishing to explore all the new possibilities of the new science of PP 2.0 (https://www.meaning.ca/positive-psychology/).

I want to conclude this chapter by quoting Faabio & Tsusa (2018):

“Acceptance of change can be considered a resource to face adaptively the continuous changes of the 21st century in terms by offering strengths to find new balances within the person, with others and with different contexts, including the natural world.”

References

- Cartwright, D., & Harary, F. (1956). Structural balance: a generalization of Heider’s theory. Psychological Review, 63(5), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046049

- Chen, S. X. (2008). Harmony. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), The encyclopedia of positive psychology (pp.464-467). Blackwell Publishing.

- Dambrun, M., & Ricard, M. (2011). Self-centeredness and selflessness: A theory of self-based psychological functioning and its consequences for happiness. Review of General Psychology, 15(2), 138-157. https://doi.org/10.1037%2Fa0023059

- David, S. (2016). Emotional agility: Get unstuck, embrace change, and thrive in work and life. Avery.

- Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Wissing, M. P., Araujo, U., Solano, A. C., Freire, T., Hernández-Pozo, M. D. R., Jose, P., Martos, T., Nafstad, H. E., Nakamura, J., Singh, K. & Soosai-Nathan, L. (2016). Lay definitions of happiness across nations: The primacy of inner harmony and relational connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(3), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00030

- Faabio, A. D. & Tsusa, A. (2018). The Psychology of Harmony and Harmonization: Advancing the Perspectives for the Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 10(12), 4726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124726

- Gruman, J. A., Lumley, M. N., & González-Morales, M. G. (2018). Incorporating balance: Challenges and opportunities for positive psychology. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 59(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000109

- Hanh, T. N. (1992). Peace is every step: The path of mindfulness in everyday life. Bantam.

- Hanh, T. N. (2014). No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming Suffering. Parallax Press.

- Haybron, D. M. (2013). Happiness: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Heider, Fritz (1946). “Attitudes and Cognitive Organization”. The Journal of Psychology. 21: 107–112. doi:10.1080/00223980.1946.9917275. PMID 21010780.

- Heine, S., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. (2006). The Meaning Maintenance Model: On the coherence of social motivation. Personality and Social Psychological Review, 10, 88-111. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1

- Jacobs, T. (2017). Struggling to reconcile conflicting beliefs? Listen to some Mozart. Pacific Standard. ) https://psmag.com/social-justice/struggling-to-reconcile-conflicting-beliefs-listen-to-mozart-47766?fbclid=IwAR3AWIwsiRXjzMGszxVf6Bd-fgzk4IKSN2NmvkdcpTqENscXI8YT9d_mfMA

- Kamenetz, R. (1996, May 5). Robert Thurman doesn’t look Buddhist. The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/05/magazine/robert-thurman-doesn-t-look-buddhist.html

- Klein, G. (2007). Performing a project premortem. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2007/09/performing-a-project-premortem

- Laozi. (2016) Tao Te Ching. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. (Original Work published ca. 400 B. C. E.)

- Leung, A. (2018). Why confronting paradoxes can give you a creative boost. Society for Personality and Social Psychology. http://www.spsp.org/news-center/blog/confronting-paradoxes-creative#gsc.tab=0

- Lomas, T. (2016). Flourishing as a dialectical balance: emerging insights from second-wave positive psychology. Palgrave Commun, 2, 16018. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.18

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803-855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

- Ponti, C. (2017). ‘Emotional diversity’ is more important than happiness. The Cut. https://www.thecut.com/2017/08/emotional-diversity-is-more-important-than-happiness.html

- Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 9(1), 139–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9023-4

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- The editors of TIME. (2019). The science of stress: Manage it. Avoid it. Put it to use [Special ed.].

- Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 678–691. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile. In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Chinese positive psychology revisited. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/174/157

- Wong, P. T. P. & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2020). How to Find Inner Peace & Life Balance in Times of Crisis?. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-concluding-chapter-how-to-find-inner-peace-life-balance-in-times-of-crisis/

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.