[This paper is a based on Wong’s (2022a) virtual presentation at the Positive Psychology in Cultural and Contextual Perspectives Symposium, delivered on April 26, 2022.]

Abstract

In a global village, it is not possible to develop a complete positive psychology without taking into account cultural and contextual perspectives. This paper discusses three areas: (a) The necessity for understanding both the human universals or existential givens and indigenous psychology, (b) The need for understanding suffering as an essential aspect of life and the “Yin” half of the Tai-chi symbol, essential for a complete account of wellbeing and flourishing, and (c) The seven principles of self-transcendence as the proven strategies for transcending suffering and contributing to human flourishing even in times of suffering and chaos. This approach represents the emerging paradigm of existential positive psychology (EPP or PP2.0), which is based on Yin-Yang dialectics and the middle way as life intelligence or existential wisdom, needed to navigate a dynamic balance between suffering (Yin) and happiness (Yang).

Keywords: Existential Positive Psychology (PP2.0), Yin-Yang dialectics, existential wisdom, suffering, self-transcendence

中文摘要

在現今世界地球村中,如果不考慮文化和脈絡觀點,就不可能發展出完整的正向心理學。本文討論了三個方面:一、 理解人類普遍性或存在的既定本質與本土心理的必要性;二、了解就如同「陰」是太極圖不可或缺的另一面一樣,受苦是人生中的本然面向,也是完整描述幸福(wellbeing)和心盛繁榮(flourishing)的必要因素;三、說明自我超越的七項原則,是經過驗證的超越痛苦和促進人類心盛繁榮的策略,尤其是在苦難和混亂的時代。本文提出重視苦難或陰暗面是幸福的必要性之取向,也是作者倡導的「存在正向心理學」(Existential positive psychology , EPP 或 PP2.0)的新興範式,這是基於「陰陽辯證」以及生命智能(life intelligence, LQ)或實存智慧(existential wisdom)的中道思想,真正的幸福需要在苦(陰)與樂(陽)之間取得動態平衡。

關鍵字:存在正向心理學、第二波正向心理學、陰陽辯證、實存智慧、自我超越

“One does not become fully human painlessly.” – Rollo May

The main themes of American positive psychology (PP), as launched by Martin Seligman as the American Psychological Association’s President (Seligman, 1999, 2002, 2011; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) can be summarized as follows:

- Peace and prosperity are the ideal conditions for PP.

- The focus is on human experiences in neutral and positive territories.

- Main research themes are positive emotions, positive traits, and positive institutions.

- PP models after STEM disciplines and attempts to be quantifiable, mechanistic, and value-free.

The above summary clearly indicates that PP is based on a Eurocentric worldview and from a different era of peace and prosperity. Much has changed since 1998. In the 21st century, we first had the 9/11 terror attack, followed by a prolonged war in Afghanistan. Recently, we witnessed the global devastations of the pandemic and international crisis caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It is increasing difficult for people to deny or dismiss the effects of suffering on their lives.

In addition, more and more research findings have challenged the assumption that we only need to focus on the positive. There is now a critical mass of empirical evidence regarding the upside of negative emotions and the downside of positive emotions (Carson, 2020; Gruber et al., 2011; Kashdan & Biswas-Diener, 2014; Mayer & Vanderheiden, 2019; Vanderheiden & Mayer, 2021; Wong, 2019a).

Therefore, happiness or wellbeing needs both (a) actions that enhance happiness or wellbeing (e.g., the Yang half of Tai-chi symbol) and (b) actions that reduce of transform suffering (e.g., the Yin half of Tai-chi symbol). We need a two-factor theory of wellbeing, or a dual-system model (Wong, 2012), to explain the process of navigating between the Yin and Yang. Existential positive psychology (EPP or PP2.0) is the study of how to live well and die well, and how to navigate the dynamic balance between happiness and suffering. From the perspective of EPP, to end or transcend all suffering is the beginning of happiness; the most promising way to flourish is through the narrow gate of suffering.

In the last 20 years, many researchers have criticized positive psychology’s narrow focus on positivity, positivism, and its Eurocentric orientation (Ehrenreich, 2009; Friedman & Robbins, 2012; Held, 2004; Wong, 2011; Wong & Roy, 2018). Most of the criticisms come from humanistic-existential psychologists.

Major Critiques of Positive Psychology

The International Handbook of Positive Psychology, edited by Chang et al. (2022), indicates both the scope and depth of change since the initial publication of the Handbook of Positive Psychology, edited by Snyder & Lopez (2001). The book description of the original Oxford handbook states:

“The Handbook of Positive Psychology provides a forum for a more positive view of the human condition. In its pages, readers are treated to an analysis of what the foremost experts believe to be the fundamental strengths of humankind.”

Now fast forward to 2022 and see the changes in the new International Handbook. The introduction to this handbook edited by Chang et al (2022) is entitled: The Making of a Global Positive Science of Human Existence: From Appreciating Existential Foundations to Identifying WEIRD Research Trends. The title alone already indicates the two emergent trends as a corrective to the initial handbook. Chang and colleagues write:

“In the present chapter, we begin with a brief introduction to the rise of modern positive psychology. We then trace the foundations of positive psychology to two central themes represented in existential scholarship, namely, a focus on the power of being human and the importance of being happy with others. Next, we tackle the question of whether or not positive psychology has truly become an international movement by examining the publication trends of the top three journals covering positive psychological research from 2000 to 2018. As our findings show, much of the research on positive psychology remains dominated by research produced in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) countries, especially the USA, that are conducted by WEIRD researchers.”

The chapter by Wong and Tweed (2022) highlight the same two emerging trends. Firstly, they emphasize that each ethnic/cultural group shapes its people “about what is worthy, good, and desirable, and about what constitutes the good, virtue, morality, health, and well-being (Christopher, Wendt, Marecek, & Goodman, 2014, p. 5).” There is increasing research indicating that well-being or life satisfaction is sensitive to cultural factors (Diener & Suh, 2000; Ujimoto et al., 1993; Wong & Ujimoto, 1998). Wong and Tweed (2022) conclude that global wellbeing needs to take into account both what is universal about human nature and what is unique about each indigenous culture in the experience and expression of human universals.

Secondly, they emphasize the need to understand the dark side of human existence. PP is mainly interested in “understanding how people rise from zero to positive eight” (Gable & Haidt, 2005). There is little research in studying how people can rise from negative eight to positive eight, with the exception of post-traumatic growth (PTG), which was developed by in the mid-90s (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996).

However, most human suffering requires more than the resilience needed for PTG. Consider the victims of online promises of romance and get rich fast scams; they suffer both emotionally and financially because they resort to the easy but foolish ways of meeting their need for love and money. Also consider those who attempt to escape from boredom, loneliness, or inner pain through substance abuse or gambling and unwittingly become victims of addition. This list can go on and on to illustrate that resilience is not enough; what we need most is wisdom and spirituality to overcome trials and temptations that will come to all of us at some point in life (McLaughlin & McMinn, 2022).

In sum, Wong and Tweed (2022) emphasize the humanistic values, the dark side of human existence, and dialectical principles (Ivtzan et al., 2015; Wong, 2011b). Wong’s research in EPP is characterized by two distinctive themes: (a) existential positive psychology with suffering as the foundation for happiness and wellbeing, and (b) indigenous psychology with the Yin-Yang concept as an Asian view of wellbeing (Wong 2020a).

The Positive Psychology of Suffering

I have detailed how and why I have developed the positive psychology of suffering in spite of the persistent resistance from the gatekeepers of PP (Wong, 2019b). By nature, no one wishes for more suffering, but at a deeper level, we realize that some suffering is both necessary and beneficial. Suffering is widely accepted in traditional or old cultures, such as those in China and India, but in the modern consumer culture of North America, suffering was still a taboo word until very recently, because suffering does not sell.

“We live in a culture that only wants to talk about what’s going well. Anything that’s not going well is positioned as a detour from the main road. The truth is that pain is not a detour from the main road. Pain is part of the road we walk as human beings.”

– Susan Cain

No one can live a life completely free from stress and suffering. This is not only truism, but also has empirical support (Fowers et al., 2017; Gruber, 2012; Robson, 2021; Wong, 2019; Wong, Mayer, & Arslan, 2021). In addition, there is a large existential literature on existential suffering, and unconscious traumas (Amelie, 2017; Jung Society of Washington, 2019; Wong & Yu, 2021; Yalom, 1980).

Therefore, how to overcome suffering (Bland, 2020; Mayer, 2021; Wong & Yu, 2021) has moved to the front and center of our consciousness and cultural narrative during the pandemic. At the same time, the perils of pursuing happiness (Wong, 2007; Zerwas & Ford, 2021) and the harmful effects of toxic positivity (Kaufman, 2021; Princing, 2021; Scully, 2020; Villines, 2021) have attracted increasing public attention.

From the perspective of Buddhist psychology, the first noble truth is that life is suffering because our desires for carnal happiness and our ignorance of the impermanence of life are the major sources of suffering (Hanh, n.d.; Targ & Hurtak, 2006; Thera, 2004). That is why Buddha’s main mission is to end suffering. In Wong’s foreword (2022) to the latest PP textbook by Piers Worth, he wrote:

“The problem of suffering was posed to Seligman shortly after launching PP in 1998. His answer in his 2003 Newsletter was: ‘More commonly we overcome troubles by doing end-runs around them, by deploying our highest strengths as buffers against the setbacks of life.’ However, it is very difficult if not impossible to maneuver around suffering, especially existential suffering, because it is an inherent part of life (Fowers et al., 2017).”

In contrast, EPP considers suffering as the foundation for wellbeing. According to this view, both focusing on curing pathology without tapping into people’s inner resources and best angels—and focusing on positive emotions and traits without addressing people’s inner demons and the dark side of life—are less effective than the dialectic approach of integrating negatives and positives in achieving optimal wellbeing. Thus, the basic tenet of EPP (or PP 2.0) is that flourishing can be achieved only through embracing and integrating human suffering as its foundation. This reorientation needs more attention from researchers and practitioners (Wong, 2019a, 2021a).

The Seven Principles of Self-transcendence

Neither individualism nor collectivism is the answer to the universal human problem of intergroup and interpersonal conflicts and aggression. The most promising path is to inspire humanity to move beyond self-interest and self-care to the self-transcendental values of loving God and loving others as oneself:

“Only to the extent that someone is living out this self transcendence of human existence, is he truly human or does he become his true self. He becomes so, not by concerning himself with his self’s actualization, but by forgetting himself and giving himself, overlooking himself and focusing outward.” – Viktor E. Frankl

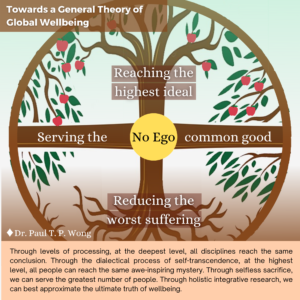

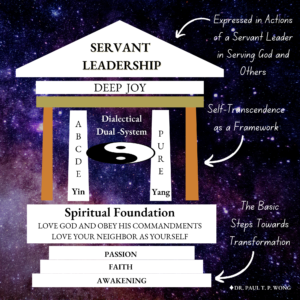

Self-transcendence works in two ways (as shown in Figure 1): 1) transcending our egotism and inherent limitations by sinking our roots into the dark soil of suffering, and 2) reaching out to our highest ideals, called God or Buddha, and spreading our branches and fruits to serve the common good.

Figure 1

Towards a General Theory of Global Wellbeing

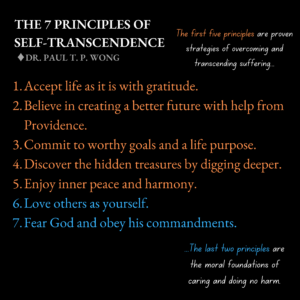

The seven principles are summarized below (Figure 2). Note that the first five principles have been presented elsewhere as the ABCDE strategy of overcoming traumas (e.g., Wong, 2016). The last two principles are considered part of the moral foundation (Graham et al., 2012) to provide the universal motivation for benevolence or compassion and to prevent people from doing harm to themselves or others.

Figure 2

The Seven Principles of Self-transcendence

1. Accept Life as it is With Gratitude

Experiential avoidance (Hayes-Skelton, & Eustis, 2020) and the tendency to avoid or escape from difficult situations (Sege et al., 2018) are a major source of anxiety and other mental disorders. Accepting life as it is rather than one’s own illusions or unrealistic expectations is an effective antidote to the human tendency of avoidance. Facing it is in most cases a more adaptive strategy. This principle has several meanings:

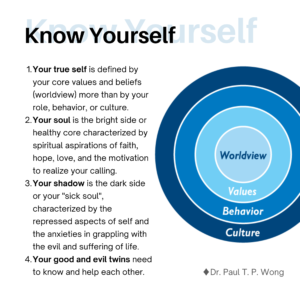

- It means to know and embrace your shadow and limitations and learn to live with your undesirable parts in order to become whole (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Becoming Whole by Knowing Yourself

- It means to accept death as a part of the life cycle and let death be our lifelong teacher: “A culture that denies death inevitably becomes shallow and superficial, concerned only with the external form of things. When death is denied, life loses its depth.” – Eckhart Tolle

- True positivity is to see and be the light in the darkest times: “When it is dark enough, you can see the stars.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

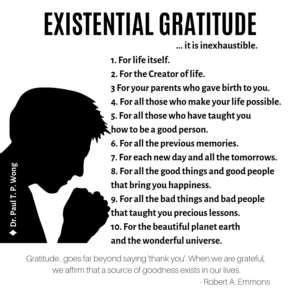

- Be grateful for everything in life, including the lessons from suffering (Figure 4). It means that we do not just accept reality grudgingly, but with a sense of gratitude not only for the painful but beneficial experience, but also for the gift of life (Jans-Beken & Wong, 2018).

Figure 4

Existential Gratitude

2. Believe in Creating a Better Future with Help from God or Providence

“Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see.” – Hebrews 11:1

Hope is like oxygen. We need to have hope for a better future in order to move forward. More importantly, we need tragic optimism (Leung et al., 2021; Wong, 2009) even in situations which seem hopeless from the human point of view. This kind of hopeless hope requires faith:

- Faith requires one to have hope in the future and confidence is what is yet invisible. If one has all the facts and information, there is no need for faith. According to Leo Tolstoy, “Faith is the sense of life, that sense by virtue of which man does not destroy himself, but continues to live on. It is the force whereby we live.”

- All the seemingly impossible things in this world are accomplished by people with faith in their visions. Martin Luther King Jr. is one example: “Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.” Another example would be Dr. Sun Yat-Sen. His story of ending the Qi Dynasty and establishing the Republic of China is a story of faith and a noble vision.

3. Commit to Worthy Goals and a Life Purpose

In addition of Frankl’s (1946/1985) classic Man’s Search for Meaning, there are several popular and helpful books on the subject of finding one’s life purpose, such as Warren’s (2013) The Purpose Driven Life and Tolle’s (2008) A New Earth. Purpose can be understood at three levels – the ultimate meaning of human existence, one’s overall life purpose, or the objective of a specific task (Wong, 2014).

I have already briefly discussed that the direct pursuit of happiness may be a source of our unhappiness. Emmons (2005) also believes that direct pursuit of happiness can be counterproductive, and it is better to pursue worthwhile projects which do not have the attainment of personal happiness as their primary focus (p. 733).

Frankl (1946/1985) makes love as the center point of meaning, because at the end of your life, you will find your life meaningful, not because of how much money you have made, but because of how much value you have created for others through your kindness, love, and compassion: “Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man through love and in love.”

4. Discover the Hidden Treasures by Digging Deeper.

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.” – Joseph Campbell

“I find that if you dig deep enough you can almost always find something worth the effort.” – Vivian Shaw

The most precious things in life are on the other side of fear. If you dig deep enough and search wide enough, you will always find a way out or get what you are looking for, whether it is a solution for a problem or finding a soul mate. Seek, and you shall find, but you have to keep on seeking and digging. My deep and wide hypothesis (Wong & Worth, 2017) has considerable empirical support. Your life can be an exciting adventure only when you dare to venture out into the ocean and move far, far from the shallow end.

5. Enjoy Inner Peace and Harmony

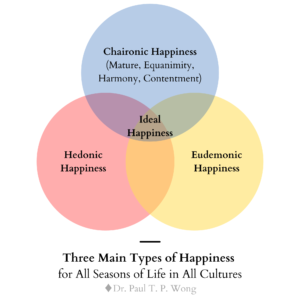

There are three major types of happiness as shown in Figure 5. The only type of happiness that is sustainable in times of suffering and chaos is the spiritually oriented mature happiness (Wong, 2021b; Wong & Bowers, 2018).

Figure 5

Three Major Types of Happiness

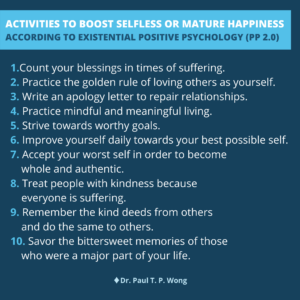

This kind of happiness is based on being attuned with the self, with others, and with God, resulting in inner peace and harmony (Wong, 2014, 2020b). In other words, true happiness is an inside joy – you need to be at peace with yourself and resolve your inner conflicts. The activities that cultivate mature happiness, as shown in Figure 6, are quite different from those required for hedonic or eudaimonia happiness.

Figure 6

Activities to Boost Selfless or Mature Happiness

6. Love Others as Yourself

This is an overall life attitude of benevolence or caring for others as caring for oneself. This principle recognizes both the personal responsibility of self-care and self-compassion (Neff, 2011) and the social responsibility of caring for others as much as caring for ourselves. What the world needs most is social interest (Adler, 1933/1964) or self-transcendence (Frankl, 1946/1985; Wong et al., 2021). Thus, individuals are both a separate unit responsible for how we live and relate to others, and at the same time part of the human family who deserve our love and compassion. This balanced attitude can reduce conflicts between egos and promote world peace.

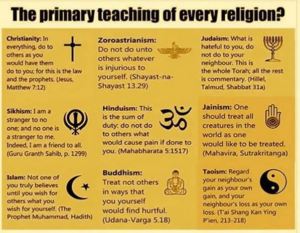

To extend this idea further, all life is sacred, and we need to love all sentential beings, according to Buddhism. Albert Schweitzer, a Christian medical missionary, made a sense of reverence for all of life as his mission: “If a man loses his reverence for any part of life, he will lose his reverence for all of life.” The golden rule of loving others as oneself is the basis for all major religions as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7

The Golden Rule in all the Major World Religions

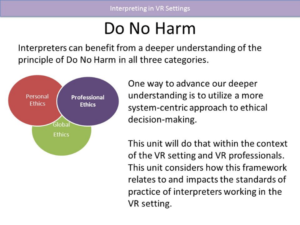

7. Do No Harm – Fear God and Obey His Commandments

“Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: Fear God and keep His commandments, for this is the whole duty of man.” – Ecclesiastes 12:13

The fear of God or a Higher Power is a needed to remind us of our boundaries and our need to fear the consequences of harming ourselves or others by going beyond our boundaries. Most human tragedies happen for two reasons:

- Someone wants to be like God. Power-hungry and ambitious individuals like Hitler, Stalin, or Putin would do harm to millions of people to secure their power and control, because they have no fear of God’s judgement. Although the statement “If there is no God, everything is permitted” is widely attributed to Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (Sartre was the first to do so in his Being and Nothingness), he simply never said it. Without such transcendental limits – so the story goes – there is nothing ultimately to prevent us from ruthlessly exploiting our neighbours, using them as tools for profit and pleasure, or enslaving, humiliating, and killing them in their millions. All that stands between us and this moral vacuum, in the absence of a transcendental limit, are those self-imposed limitations and arbitrary “pacts among wolves” made in the interest of one’s survival and temporary wellbeing, but which can be violated at any moment. (Zizek, 2012).

We need to act as if God exists (i.e., God watches us and holds us accountable). Voltaire repeatedly asserted that “if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.” He meant that belief in God and ultimate justice is necessary to ensure that we may be prevented from doing horrible things to each other as evident in the Holocaust.

- Related to the first reason, we need to obey God’s commandments so we do not cross the red line. In the case of Adam and Eve, the red line was eating the forbidden fruit. The same command is still helpful today. The battle between good and evil, or between the Spirit and the flesh, is raging on in every one of us. Even Saint Paul was tormented by his inner struggles:

“For I know that good itself does not dwell in me, that is, in my sinful nature. For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing.” (Romans 7:18-19).

We all have experienced such inner struggles. Some could not control their lust for sex. Others find it extremely difficult to resist the greed for more money or power. For each of us, what is most attractive, most difficult to resist may be our forbidden fruit. There are always consequences when we disobey God’s commandments. Even if one does not believe in God, the law of karma still operates. We always reap what we sow.

In sum, this last principle represents the universal ethical rule of nonmaleficence, or do no harm, as illustrated by Figure 8.

Figure 8

The Universal Ethical Rule of Nonmaleficence

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would say that in times like this, the best possible life is based on EPP, as depicted by Figure 9. Self-transcendence is the conceptual framework. The 7 principles are needed to embrace and transcend suffering. The best possible mental health is the optimal balance between suffering and happiness through the dialectical dual system model (Wong, 2012). ABCDE is needed to overcome suffering, while the PURE model of Purpose, Understanding, Responsibility and Enjoyment is needed to achieve a meaningful life (Wong, 2016).

Learning to embrace and transcend suffering is essential for happiness. The best possible life is bittersweet, because optimal happiness is the optimal balance between negative and positive emotions.

In sum, the best possible life is to live in harmony with self, others, and God or nature, expressed in actions of serving a higher purpose and the common good. To cultivate this kind of life requires life intelligence through counselling or life education (Wong, 2022a).

Figure 9

Wong’s Model of Existential Positive Psychology and Integrative Meaning Therapy

References

- Adler, A. (1964). Social interest: A challenge to mankind (J. Linton & R. Vaughn, Trans.). Capricorn Book. (Original work published 1933)

- Amelie. (2017, October 15). Unconscious trauma can affect your quality of life. Inner Optimal. https://myoptimalbrain.com/unconscious-trauma-life-quality/

- Bland, A. M. (2020). Existential Givens in the COVID-19 Crisis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(5), 710–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820940186

- Carson, E. (2020, October 29). The dark side of the pursuit of happiness. Cnet. https://www.cnet.com/news/the-dark-side-of-the-pursuit-of-happiness/

- Chang, E. C., Downey, C. A., Yang, H., Zettler, I., & Muyan, M. (2022). The international handbook of positive psychology: A global perspective on the science of positive human existence. Springer.

- Diener, E. & Suh, E. M. (Eds.). (2000). Culture and subjective well-being. MIT Press.

- Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America. Henry Holt and Company.

- Emmons, R.A. (2005). Striving for the sacred: Personal goals, life meaning, and religion. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 731-746.

- Fowers, B. J., Richardson, F. C., & Slife, B. D. (2017). Frailty, suffering, and vice: Flourishing in the face of human limitations. American Psychological Association.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press. (Originally published in 1946)

- Friedman, H. L., & Robbins, B. D. (2012). The Negative Shadow Cast by Positive Psychology: Contrasting Views and Implications of Humanistic and Positive Psychology on Resiliency. The Humanistic Psychologist, 40, 87-102.

- Gable, S. L., & Haidt, J. (2005). What (and Why) is Positive Psychology? Review of General Psychology, 9, 103 – 110. Doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S. P., & Ditto, P. H. (2012). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 58-130). Elsevier

- Gruber, J. (2012, May 3). Four ways happiness can hurt you. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/four_ways_happiness_can_hurt_you/

- Gruber, J., Mauss, I. B., & Tamir, M. (2011). A Dark Side of Happiness? How, When, and Why Happiness Is Not Always Good. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611406927

- Hanh, T. N. (n.d.). The end of suffering. Science and Nonduality. https://www.scienceandnonduality.com/article/the-end-of-suffering

- Hayes-Skelton, S. A., & Eustis, E. H. (2020). Experiential avoidance. In J. S. Abramowitz & S. M. Blakey (Eds.), Clinical handbook of fear and anxiety: Maintenance processes and treatment mechanisms (pp. 115–131). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000150-007

- Held, B. S. (2004). The Negative Side of Positive Psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44(1), 9-46.

- Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second wave positive psychology: Embracing the dark side of life. Routledge.

- Jans-Beken, L. G. P. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Development and preliminary validation of the Existential Gratitude Scale (EGS). Counselling Psychology Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1656054

- Jung Society of Washington. (2019). The psyche keeps score: A Jungian view of Trauma. https://www.jung.org/blog/7870232/

- Kashdan, T., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2014). The upside of your dark side: Why being your whole self–not just your “good” self–drives success and fulfillment. Avery.

- Kaufman, S. B. (2021). The opposite of toxic positivity: Tragic optimism. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/08/tragic-optimism-opposite-toxic-positivity/619786 /

- Leung, M. M., Arslan, G., & Wong, P. T. P. (2021). Tragic Optimism as a Buffer against COVID-19 Suffering and the Psychometric Properties of a Brief Version of the Life Attitudes Scale (LAS-B). Frontiers, 12, 646843. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646843

- Mayer, C.-H. & Vanderheiden, E. (2019). The Bright Side of Shame. Transforming and growing through practical applications in cultural contexts. Springer.

- Mayer, C.-H. (2021). Albert Camus – A psychobiographical approach in times of Covid-19. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644579

- Mclauglin, P. T., & Mc Minn, M. R. (2022). A time for wisdom: Knowledge, detachment, tranquility, transcendence. Templeton Press.

- Neff, K. (2011). Self-Compassion: Stop Beating Yourself Up and Leave Insecurity Behind. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Princing, M. (2021, September 8). What you need to know about toxic positivity. Right as Rain. https://rightasrain.uwmedicine.org/mind/well-being/toxic-positivity

- Robson, D. (2021, January 10). Why it’s time to stop pursuing happiness. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/jan/10/why-its-time-to-stop-pursuing-happiness

- Scully, S. M. (2020, July 22). ‘Toxic positive’ is real – and it’s a big problem during the pandemic. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/toxic-positivity-during-the-pandemic

- Sege, C. T., Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2018). Avoidance and escape: Defensive reactivity and trait anxiety. Behaviour research and therapy, 104, 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.03.002

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1999). The APA 1998 annual report. American Psychologist, 54(8), 537-568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.537

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Free Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. The American psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5

- Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (Eds.) (2001). Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Targ, R., & Hurtak, J. J. (2006). The end of suffering: Fearless living in troubled times…or, how to get out of hell free. Hampton Roads Publishing.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02103658

- Thera, N. (2004). Why end suffering? Access to Insight. https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nyanaponika/whyend.html

- Tolle, E. (2008). A new earth: Awakening to your life’s purpose. Penguin Life.

- Ujimoto, K. V., Nishio, H. K., Wong, P. T. P., & Lam, L. (1993). Cultural factors affecting the self-assessment of health satisfaction. In R. Masi, L. Mensah, & K. McLeod (Eds.), Health and culture: Explaining the relationships (pp. 229-240). Canadian Council on Multicultural Health.

- Vanderheiden, E., & Mayer, C.-H. (2021). Transforming Shame during Covid-19: An International Study. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641076

- Villines, Z. (2021, March 30). What to know about toxic positivity. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/toxic-positivity/

- Warren, R. (2013). The purpose driven life: What on earth am I here for? Zondervan.

- Wong, P. T. P. & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). IGI Global.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2007). Perils and promises in the pursuit of happiness [Review of the book In search of happiness: Understanding an endangered state of mind]. PsycCRITIQUES, 52(49).

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 52(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011b). Reclaiming positive psychology: A meaning-centered approach to sustainable growth and radical empiricism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 51(4), 408-412.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). From attunement to a meaning-centred good life: Book review of Daniel Haybron’s Happiness: A very short introduction. International Journal of Wellbeing, 4(2), 100-105. doi:10.5502/ijw.v4i2.5

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). Viktor Frankl’s meaning-seeking model and positive psychology. In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.), Meaning in positive and existential psychology (pp. 149–184). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0308-5_10

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Integrative Meaning Therapy: From Logotherapy to Existential Positive Interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyany (Eds.), Clinical Perspectives on Meaning: Positive and Existential Psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). Springer International Publishing.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019a). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019b). Why and How I Developed the Positive Psychology of Suffering. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. http://www.drpaulwong.com/why-and-how-i-developed-the-positive-psychology-of-suffering/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020a). The maturing of positive psychology and the emerging PP 2.0 [Book review of Positive Psychology (3rd ed.) by William Compton and Edward Hoffman]. International Journal on WellBeing, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i1.885

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). How to Find Inner Peace & Life Balance in Times of Crisis? In P. T. P. Wong, Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 According to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021a). Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) and global wellbeing: Why it is Necessary During the Age of COVID-19. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 10(1), 1-16. https://www.meaning.ca/ijepp-article/vol10-no1/what-is-existential-positive-psychology-pp-2-0-why-is-it-necessary-for-mental-health-during-the-pandemic/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021b, August 6-8). Introduction. In P. T. P. Wong (Chair), Global wellbeing during the pandemic: Honouring Ed Diener [Symposium]. International Network on Personal Meaning 11th Biennial International Meaning Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022a, April 26). The best possible life in a troubled world: An existential positive psychology perspective [Symposium]. Positive Psychology in Cultural and Contextual Perspectives. http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-best-possible-life-in-a-troubled-world-an-existential-positive-psychology-perspective

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022b). Foreword. In P. Worth (Ed.), Positive Psychology Across The Life Span An Existential Perspective. Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Roy, S. (2018). Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), Routledge international handbooks. The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology (pp. 142–160). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Tweed, R. (2022). Positive psychology in North America. In E. C. Chang, C. A. Downey, H. Yang, I. Zettler, & M. Muyan (Eds.), The international handbook of positive psychology: A global perspective on the science of positive human existence. Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Ujimoto, K. V. (1998). The elderly: Their stress, coping, and mental health. In L. C. Lee, & N. W. S. Zane (Eds.), Handbook of Asian American psychology (pp. 165-209). Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Worth, P. (2017). The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity [Special issue]. Psychology and Education, 54(3/4). from http://www.psychologyandeducation.net/pae/category/volume-54-no-3-4-2017/

- Wong, P. T. P., & Yu, T. T. F. (2021). Existential suffering in palliative care: An existential positive psychology perspective. Medicina, 57(9), 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090924

- Wong, P. T. P., Arslan, G., Bowers, V. L., Peacock, E. J., Kjell, O. N. E., Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T. (2021). Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the Self-Transcendence measure-B. Frontiers, 12, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648549

- Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., & Arslan, G. (Eds.). (2021). COVID-19 and Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0): The new science of self-transcendence [Special Issue]. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/14988/covid-19-and-existential-positive-psychology-pp20-the-new-science-of-self-transcendence

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

- Zerwas, F. K., & Ford, B. Q. (2021). The paradox of pursuing happiness. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 39, 106-112.

- Zizek, S. (2012, April 17). If there is a God, then anything is permitted. ABC Religion & Ethics. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/if-there-is-a-god-then-anything-is-permitted/10100616

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2022). The best possible life in a troubled world: The seven principles of self-transcendence [亂世中活出最好的人生:自我超越的七項原則]. Positive Psychology in Counseling and Education. DOI:10.30099/PPCE.202206_(1).0001

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.