*This is an unrevised version of the paper.

(This paper was co-authored with Gökmen Arslan, Victoria L. Bowers, Edward J. Peacock, Itai Ivtzan, and Tim Lomas. The paper is partially supported by a 3-year Templeton Grant; Wong (the lead author) was part of a working group of philosophers, theologians, and psychologists wrestling with the topic of virtue, happiness, and meaning. Given the absence of a general psychological theory and a valid measure of self-transcendence, Wong’s project in that research working group was to fill this void. All of Wong’s presentations were first posted on Wong’s personal website. Only one presentation was published as a journal article; the rest of the materials were further developed and published for the first time.)

Abstract

The age of COVID-19 calls for a different approach towards global wellbeing and flourishing through transcending suffering as advocated by existential positive psychology. In the present paper, we first explain what self-transcendence is and why it represents the most promising path for human beings to flourishing through transforming suffering in a difficult and uncertain world. After reviewing the literature of self-transcendence experiences, we conclude that Frankl’s model of self-transcendence is able to integrate both of the characteristics associated with self-transcendence. Then, we discuss how Wong’s self-transcendence paradigm, an extension of Frankl’s model, may to help awaken our innate capacity for connections with the true self, with others, and with God or something larger than oneself. We present self-transcendence as a less travelled but more promising route to achieve personal growth and mental health in troubled times.

Finally, we present the history of development and the psychometrics of the Self-Transcendence Measure-B (STM-B) and report the empirical evidence that self-transcendence served as a buffer against the COVID-19 suffering. The present data suggest that the best way to overcome pandemic suffering and the mental health crisis is to cultivate self-transcendence.

Keywords. self-transcendence, meaning, COVID-19, existential positive psychology (PP 2.0), existential psychology, positive psychology, mature happiness, wellbeing, suffering

“The essence of life is to serve others and do good.”- Aristotle

Introduction

The human costs of the pandemic in terms of mortality, morbidity, mental health conditions, and direct economic losses are staggering (Cutler & Summers, 2020; Graham 2020). Even with three vaccines, the CDC still warns of a 4th wave of COVID-19 (Soucheray, 2021). The pandemic may persist for years, according to the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada (Aiello, 2020). The pandemic has destroyed countless businesses and careers. It becomes more challenging to rebuild one’s career or start a new one. Again, one needs to be equipped with mental toughness to excel in whatever one pursues. The positive illusion of focusing only on the positive side of life will not carry one very far in a world full of cut-throat competition and human evils of deception and discrimination.

For people who have lost everything, the struggle may seem like the futile attempt of endlessly pushing a rock uphill (Camus, 1942/1955). The pandemic fatigue may turn into pandemic burnout (Millard, 2021). The universality of suffering is a fact that we can no longer deny or avoid in the age of COVID-19. The natural tendency to avoid or escape from the pain life may icreate more problems for us. Paradoxically, the greatest discovery of dialectical psychology is radical acceptance–to embrace and make the best use of all of one’s pain for a better life is a better alternative to find healing and flourishing.

However, our optimistic view (Wong, 2020a, 2021a, in press) is based on the empirical evidence (Bethelmy & Corraliza, 2019; Lin et al., 2021; Worth & Smith, 2021; Yaden & Newberg) regarding the power of self-transcendence, which comes from altruism (Feigin et al., 2014), religious faith (Koenig, 2009), meaning (Wong, 1998), and the feeling of awe (Yaden et al., 2017). According to Wong (2021b), It is the worst of times, but it is also the best of times. But we cannot celebrate the best without overcoming and transcending the worst. This sums up the power of self-transcendence, which achieves the dual purpose of transforming suffering into resilience and motivating us to pursue the highest ideals. This vertical dimension of self-transcendence is often neglected, because current psychology research tend to focus on the horizontal dimension of self-actualization, pro-social behaviors and the emotion of awe.

In sum, when probably understood, self-transcendence represents what is good and noble about humanity. It is like a symphony celebrating the heroic efforts of those who sacrifice themselves in order to lift others up above their suffering to a higher ground of faith, hope, and love. More importantly, it has the power of inspiring countless others to transcend their petty egotistic concerns and serve something greater than themselves. However, this mega shift demands more than individual endeavour; it also requires a collective effort to co-create a more just and compassionte society.

At this crucial juncture of history, it is advisable to examine honestly and deeply our cultural beliefs and our own existential crisis. In this article, we intend to explain and demonstrate empirically why self-transcendence can not only buffer us against COVID-19, but also transform us from self-centered, and self-absorbed existence to a self-transcendent and fulfilling life.

Cushman’s (1990) social historical analysis of “the empty self phenomenon” is still relevant to the current meaning crisis. He pointed out the broad historical forces, such as industrialization, urbanization, and secularism have shaped Western culture and influenced the predominant psychological view of human beings as bounded, autonomous, masterful, but with an empty self. America is the one of the richest countries, but is also one of the emptiest one because Americans try to fill their inner emptiness with the consumption of products, drugs, psychotherapy, or happiness coaches. Such efforts are self-defeating because our spiritual yearning for meaning can only be filled by constitutive goods, which are intrinsic to human existence, such as friendship, justice, and prosocial behavior.

The main argument of Cushman’s paper is that “in a world sorely lacking in community and tradition, the most effective healing response would be to address those absences through structural societal change by reshaping political relationships and cultural forms and re-establishing the importance of their transmission.” (p. 607). He raises the important question:

“Could psychology now become a helpful force, assisting in the development of a perspective on the masterful, bounded self in opposition to the current system? Given the history of the Western self, and the role of psychology within that history, it is doubtful.” (p. 609)

In view of Cushman’s analysis, our current mental health crisis is partly one of our own making with the misguided Western conception of human beings as self-contained masterful individuals, who are entitled to feel happy everyday by consuming instrumental rather than constitutive goods. Constitutive goods are natural and intrinsic goods, such as connections with the self, with others, and with God, because of our human nature, according to Wong’s self-transcendence paradigm (Wong, 2020a, 2021a). More importantly, we hope that this push for a change of direction in psychology will also drive the public dialogue of how to restore civil virtues and spiritual values in our culture, such as responsibility, cooperation, altrusism, reverence for life, and benevolence.

Self-transcendence (ST) is important for psychology and society because it is a promising way to balance self-interest with social interest. Consistent with Cushman’s analysis, mainstream psychology still focuses on the scientific study of different aspects of the self as a masterful individual, such as internal locus of control, self-efficacy, self-control, self-esteem, signature character strengths, and achievement. However, during difficult times, such as this pandemic, survival and flourishing depend on our ability to transcend adversity and selfishness by making the necessary sacrifices for the common good. There is an urgent need for public awareness of the importance of WE over ME in times of national crisis.

Paradoxically, the power of ST in contributing to wellbeing, resilience, and the richness of our life seems to come from embracing and transcending suffering; from losing ourselves in the beauty and goodness around us, to sacrificing immediate gratification in pursuing a long-term worthy life goal to serve the common good. In the final analysis, it appears that developing the capacity to endure and trascend our misfortunes, traumas, suffering,s and fears over and over again in order to serve something or someone more important for surving and thriving, especially in the era of COVID-10. . The first author’s lifelong research and clinical practice supportS this proposition. This is the core message of this paper.

What is Self-Transcendence

According to the American Psychological Association, self-transcendence is “the state in which an individual is able to look beyond himself or herself and adopt a larger perspective that includes concern for others. Some psychologists maintain that self-transcendence is a central feature of the healthy individual, promoting personal growth and development [first described by Viktor E. Frankl].” (American Psychological Association, 2020a). Literally, it means to that which goes beyond one’s limitations and difficulties life experience in order to serve or become connected with something greater. According to Ackerman (2021), self-transcendence is experienced when there is a “realization that you are one small part of a greater whole, and act accordingly.” This humanness of being bound by all kinds of constraints can only be unbounded through the transcendental realm (Elmer, MacDonald, & Friedman, 2003).

The transcendence principle encompasses nature, science, religion, politics, culture, or anything that is greater or beyond human experiences (van Deurzen, 2014). Transcendence also generally refers to the complex emotions that arise from a sense of unity with other people, nature, and God, such as awe and selflessness (Keltner & Haidt 2003; Mikulak, 2015; Yaden et al, 2017).

Self-Transcendence as a Religious or Spiritual Experience

Self-transcendence involves the motivation to experience something sacred and beyond the daily mundane experience. Human existence is ordinary and material until we can perceive and take hold of the part of us that seeks out the realm of sacred experience larger than the self (Mayseless & Rutzo-Netzer, 2017). These self-transcendent sacred moments adds some deeper spiritual meaning to our lives

Self-transcendence is generally related to religious experiences. For example, William James (1902/2004) wrote: “The only thing that religious experience, as we have studied it, unequivocally testifies to is that we can experience union with something larger than ourselves and in that union find our greatest peace.” Van Deurzen (2014) pointed out that transcendence can also be related to polytheism:

“Transcendence is experienced as related to the many different gods and divine representations that need to be appeased. Many clients hold such hidden views. They say prayers to the various deities, icons, or saints they believe in and feel they will only be able to surpass their problems if the gods are favourable to them. Polytheistic beliefs often go with a strong sense of community and community support is crucial for transcendence to become possible.”

Similarly, Frey and Vogler (2019) conclude that according to research in the humanities and social sciences, individuals who are able to locate themselves in a larger or broader perspective, whether it is family, community, or religious or spiritual groups—often experience greater happiness, meaning, and virtue. More importantly, this finding is relevant to all major religions, both East and West.

Self-Transcendence as an Emotional Response of Awe

The self-transcendent emotion refers to a category of emotions such as awe, love, elevation, appreciation, etc., which connect people in social relationships (Stellar et al., 2017).

Awe is a natural emotional response to something spectacular or sacred, such as a glorious sunset or an ancient temple; this may be consistered as a deep exisrtential-spiritual response (Schneider, 2009, 2011). According to Keltner & Haidt’s (2003) cognitive interpretation, awe tends to arise from a perception of vastness and a cognitive need to accommodate one’s perception into existing mental schemas.

The importance of this transcendental emotion important for wellbeing has received increasing empirical attention (Allen, 2018; Yaden et al., 2017). For example, Bethelmy and Corraliza (2019) reported that various recent studies have demonstrated nature’s power to induce the transcendental emotion of awe. They developed an instrument to measure sublime emotion toward nature, which includes feeling of awe and inspiring energy. More recently, Clewis and colleagues (2021) discovered that there is much overlap between awe and sublime feelings, suggesting that these two literatures could inform one another. In terms of application, Passmore and Holder (2016) reported that a two week a nature-based well-being intervention increased transcendental benefits such as positive affect, elevating experiences, a general sense of connectedness (to other people, to nature, and to life as a whole) and prosocial orientation as compared to group compared to the human-built and control groups.

According to the self-transcendence model described later, there are at least 7 ways to boost the emotions of awe. We can stand in awe of the folliwng phenomenas:

- The power of life force to grow and bear fruits against all odds.

- The wisdom of human mind to probe into the mystery of life.

- The virtue of love in sacrificing the self for others.

- The magic of gratitude to fill our hearts with happiness.

- The invincible courage to stand up against evil.

- The unwavering faith in creating a better future.

- The unspeakable joy of losing oneself to become a part of something greater (e.g, nature or Creator).

Self-Transcendence as Altruistic and Prosocial Behavior

Self-transcendence has both a vertical and horizonal dimension. We can transcend upward towards God, nature, or an invisible spiritual realm, and we can also transcend towards others by serving and connecting with them. We propose that our innate self-transcendence tendence can account for altruistic, helping, and prosocial behaviors. This tendency can be reinforced by the intrinsic feeling good from doing good (Mruk, 2018) and the positive affect from connecting with others and meeting our need for companionship, and social and emotional support (Meek, 2012). Recently, some researchers found that the natural transcendental emotion response to some powerful stimuli is sufficient to make one forget one’s “small self” and pay attention to others or engage in prosocial behavior (Guan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Piff et al., 2015).

In contrast to egotism, altruism is motivated by our desire to increase another person’s welfare, even when it may cost something to ourselves (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006); it is the kind of prosocial behavior which benefits others without any expectation of return (Eisenberg & Miller 1987; Feigin et al., 2014). There is increasing research evidence that the natural emotional response of awe is sufficient to make one forget one’s small self and self interest and pay attention to others or engage in prosocial behavior (Li et al., 2019; Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Piff et al., 2015).

Volunteering is another form of prosocial behavior, which is very relevant for today’s retirees because it enables them to stay connected and make some contribution to society, and in return, contributes to their health and meaning in life (Midlarsky & Kahana 2007; Wilson, 2000). Recent research has confirmed that such acts of kindness contribute to one’s wellbeing (Curry et al., 2018; Hui et al., 2020).

Self-Transcendence as Virtue & Value

According to Peterson and Seligman, (2004), transcendence encompasses a number of character strengths such as appreciation of beauty gratitude, hope, humor, and religiousness (having a solid belief about a higher purpose and meaning of life); it represents one of the six virtues. Although they do not make explicit references to God or religion, Peterson and Seligman (2004) recognized the universality of religion and spirituality: “Although the specific content of spiritual beliefs varies, all cultures have a concept of an ultimate, transcendent, sacred, and divine force.” (p. 601).

Sortheix and Schwartz (2017) did large-scale studies among European countries and found that self-transcendence was positively related to subjective wellbeing. More importantly, they did not find any support for the expectation that self-transcendence might also be detrimental to subjective wellbeing because self-transcendence often entails invest more in others’ wellbeing than in their own.

Self-Transcendence as Personal Growth

Humanism is also based on the principle of self-transcendence (van Deurzen, 2014). According to humanistic psychology, self-transcendence is a growth motivation towards connecting with others. According to DeRobertis and Brand (2019):

“The purpose of the self-transcending motivational tendency is to relate to things and others in the most meaningful and profound manner, overriding (without necessarily eliminating) concern for one’s own enjoyment or self-interest.”

Wong (2016a) described self-transcendence as a paradoxical way towards personal growth; in other words, the best path towards self-actualization and personal growth is through transcending our limitations towards the greater good. His approach is based on Frankl’s meaning seeking model (Wong 2016b), which will be explained in detail later.

Maslow (1971) comes to a similar conclusion. To him, transcendence represents the highest level of human development and the higher consciousness of being connected. Thus, those who achieve self-transcendence have experienced the peak experiences and satisfied such being-needs as wholeness (unity), perfection (balance and harmony), justice (fairness), autonomy (self-sufficiency), and meaningfulness (values):

“Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos” (Maslow, 1971, p. 269).

Frankl argued that self-transcendence was merely a by-product of pursuing self-transcendence. Wong (2005) provided a similar but more detailed critique of Maslow’s hierarchical model. However, Kaufman (2020) is correct in that there is no real conflict between self-actualization and self-transcendence, because one moves freely from one state to another in a fluid manner. Actually, everyone begins with self-actualization, desiring to develop our potentials and become our best self; however, this could happen only when we are awakened to our need for b-values of being-values, such as goodness, rightness, justice; and benevolence – the kind of valuse that characterises self-transcendence. No purposes are equal. If one’s life goal is egotistic and worldly, success may result in ruining one’s life (Holiday, 2016).

Rogers’ (1961) organismic valuing theory is also moving towards the direction of self-transcendence as evidenced in Kaufman’s (2020) new science of self-actualization. Likewise, Maurer and Daukantaitė (2020) reviewed a great deal of empirical evidence supporting the connection between the organismic valuing theory of personal growth and self-transcendence. In a qualitative study of highly self-transcendent individuals, Reischer et al. (2020) confirmed that these individuals tended to narrate their lived experiences as spiritual journeys of humanistic growth toward self‐transcendence during the later middle age.

From the psychodynamic perspective, Dobson (2015) reported that self-transcendence represents personal grow towards spiritual and moral maturity:

“For Jung as well as for Kohut, one’s maturation into a whole self, one’s hoped for completion of the task of individuation is a transcendent, transpersonal act of great moral responsibility.” (p. 9).

Self-Transcendence Contributes to Mature Happiness

Life is full of dilemma, paradoxes, contradictions, and suffering. We need to face life in totality with existential courage to face suffering and death (Van Tongeren & Van Tongeren, 2020): “Courage is the universal self-affirmation of one’s Being in the presence of the threat of non-Being.” (Tillich 1952, p. 163). The only way can find ways to transcend adversity is to learn how to muster enough courage to face each day’s stress and negative emotions.

Van Deurzen (2014) provides a very useful survey of major existential philosophers to make the point that the single-minded pursuit of happiness as the end goal of life is doomed to fail. She begins by pointing out that it is not possible to think of the positive without thinking of the opposite side: “Happiness and unhappiness are twins that grow up together (Nietzsche 1882/1974:270 )”. Therefore, there is the need to transcend and integrate all the contractions and oppositions in life according to Hegel’s dialectics of synthesis from the thesis and antithesis. Greater truths and integration in life, as well as in research, can only come from such synthesis. She also cited Sartre’s notion of re-inventing oneself or re-defining a situation in order not to get stuck: “Man is characterized above all by his going beyond a situation and by what he succeeds in making of what he has been made (Sartre, 1968:91)”. Therefore, she eloquently pointed out the impossibility of personal growth and mature happiness without transcending the unavoidable and inescapable paradoxes and sufferings in human existence:

“The paradox of life is that only if we accept both aspects of these oppositions and contradictions that we can transcend our difficulties and find new and more creative ways to encompass the whole span of human ability and challenge.

It is only when we are willing to face death and pain that we can live life to the fullest, instead of worrying ourselves sick and trying to be healthy and wealthy and comfortable all the time, which leads to a life lived in fear.

It is only when we allow ourselves to notice our weakness and vulnerability that real strength is found instead of us covering up our doubts by narcissistic pretence or giving in to our fragility by self destructive denial of ourselves.”

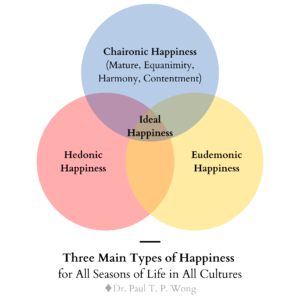

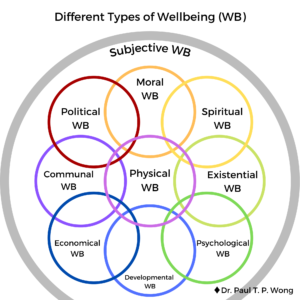

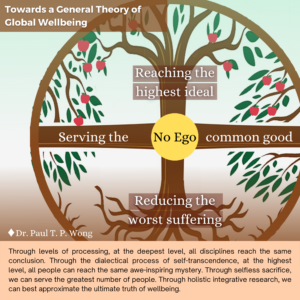

See Figure 1 depicting different types of happiness and Figure 2 for different types of wellbeing. Also see Wong’s tentative global theory of wellbeing which represents the ideal of Taoism (Figure 3).

Figure 1

Different Types of Happiness

Figure 2

Different Types of Wellbeing

Figure 3

Towards a General Theory of Global Wellbeing

Ancient philosophies, such as Taoism and Buddhism, also contribute to our understanding of mature happiness. For example, I-Ching offers the Way to live a good life in an uncertain and ever-changing world. Happiness is never just about individual pursuit, but about the way to achieve harmony as reflected by the Taoist concept of the union between Heaven and people ( 天人合一), or living in harmony with heaven, earth, and people (天地人和).

Therefore, the less travelled path to happiness is to attain inner peace and harmony with self, others, as well as Heaven and Earth.

An philosophical understanding of the paradoxes and contradictions provides the necessary background for the psychology of mature happiness. Wong and Bowers (2018) made a similar argument that mature happiness, characterized by inner peace and harmony, comes from the wisdom and courage of transcending opposites. More recently, Lomas (2021) declared that: “an overarching definition of wellbeing is offered: the dynamic attainment of optimal balance and harmony in any–and ideally all–aspects of life.” (Lomas, 2021, p. 5). Thus, in addition to the emotion of awe, mature happiness comes from cultivating wisdom, courage, and virtue in transcending suffering (Wong, 2020a, 2021a). True happiness comes from being the light to banish darkness in the world. It means the self-transcendental way of enduring the necessary suffering and self-sacrifice for the greater good. According to Wong (2021b), there are three major types of happiness as shown in Figure 1. Mature happiness is basically spiritual (noetic) happiness based on self-transcendence, but it could also be known as charionic (Wong, 2011 PP 2.0), because the Greek word for rejoicing in suffering is Χαίρετε (chairete) as found in Philipines 4:4 of the Bible.

Frankl’s Self-transcendence Model

The earliest and most influential theory of self-transcendence was developed by Frankl (1946/1985). Researchers routinely credit Frankl as the father of meaning-focused therapy, but they fail to understand Frankl’s conceptualization of meaning in terms of self-transcendence. A deep sense of meaning involves the volition of exercising one’s will to meaning to pursue self-transcendence for the common good regardless of sacrifice and suffering. Meaning is not only anchored in subjective feelings, but also in an objective behavioral commitment to devoting one’s life to loving something or someone greater than oneself, such as loving others or serving society according to one’s calling. This paradoxical truth of self-fulfillment is clearly stated in this quote:

“Only to the extent that someone is living out this self-transcendence of human existence, is he truly human or does he become his true self. He becomes so, not by concerning himself with his self’s actualization, but by forgetting himself and giving himself, overlooking himself and focusing outward.” (Frankl, 1977/2011, p. 36).

When probably understood, self-transcendence represents the most beautiful story about what is good and noble about humanity. It is the uplifting story about human beings, individually or collectively, who dedicate and sacrifice themselves in order to lift up others beyond their limitations and sufferings to a higher ground of faith, hope and love. Thus, in addition to this re-orientation, the willingness to suffer for the common good is another defining characteristic of self-transcendence, because it is not possible to achieve one’s highest ideal or deepest meaning without any sacrifice or suffering.

In short, Frankl attempted to restore the soul or the noetic (spiritual dimension) to psychology and society (Wong, 2021c). Thus, the meaning of life or self-transcendence is about developing one’s gift in order to give one’s best to serve the world (Wong, 2016a).

Research support Frankl’s definition of meaning in terms of search for self-transcendence. For example, Harris et al. (2018) show that finding meaning is an essential element of self-transcendence. McClintock (2015) report that self-transcending gratitude may be the very key to how we can become change agents of making a difference in the world. A sense of self-transcendental motivates individuals to live a meaningful life and use one’s gift to make a positive contribution to society (Wong, 2014a, 2016a).

Wong’s (2021c) remembrance of Viktor Frankl’s contribution to self-transcendence revolves around three themes:

1) Self-transcendence is an awe-filled lifestyle of serving a cause passionately.

2) Self-transcendence is the core of meaning-focused therapy and an important adject for all therapeutic dimensions.

3) Self-transcendence has become the foundation of existential positive psychology.

According to Viktor Frankl (1946/1985), self-transcendence is the essence of human nature; it presents a healthy spiritual core with its yearning to strive towards the sacred and to serving others:

“Only to the extent that someone is living out this self-transcendence of human existence, is he truly human or does he become his true self. He becomes so, not by concerning himself with his self-s actualization, but by forgetting himself and giving himself, overlooking himself and focusing outward.”

Self-transcendence involves a change of mindset from what I can get from life to what I can give to life. It involves a shift from the horizontal dimension of being preoccupied with worldly success and comfort to the vertical way of living focusing on one’s spiritual needs for meaning, personal growth and serving something sacred or greater than oneself. This quantum shift is necessary to fill the void of the empty self and enable us to become our best version in spite of internal and external limitations. That is why Frankl suggests that the best way to discover one’s calling to discover both what gift one can offer and what life demands from one’s life. Thus, we are responsible, both ethically and instrumentally, for the wellbeing of our neighbors, because we are an integral part of a relational world. That is why being ethical and benevolent towards others is an inherent part of self-transcendence (Wong & Reilly, 2017).

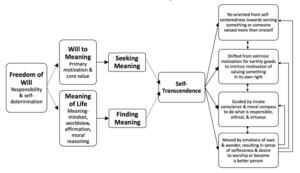

Frankl’s Two-Factor Theory of Self-Transcendence

As shown in Figure 4, Frankl’s theory of self-transcendence rests on two factors.

Figure 4

Two Factor Theory of Frankl’s Self-transcendence

Will to Meaning as the Motivational Factor

The will to meaning, the motivational factor that propels people from point “A” towards “B” through the process of self-transcendence, is considered by Frankl as a primary motivation. From the perspective of life’s terminal values, self-transcendence was one of the universal values, according to Schwartz (1992, 1994). The will to meaning consists of both push and pull motivations in one’s striving towards a meaningful goal – pushed by the soul’s yearning and pulled by a future purpose to be fulfilled.

Meaning-Mindset (MM) (Wong, 2012) as the Cognitive Factor

MM consists of one’s worldviews or assumptions affirming that life has inherent meaning and value. If mindfulness adds clarity by reducing one’s emotional reactivity, MM provides the lens that adds content and depths to one’s perception. It enables people to see things from the deeper spiritual perspective; it enables one to see the connectivity of all people and all living things and enables people to discover the significance of ordinary events. In short, we tend to discover or see what we value or search.

Contrary to positive psychology’s preference to emphasis the positive emotion of awe, Frankl’s emphasis is on the will and mindset. The MM facilitates the discovery of meaning and significance, and the selection of worthy life goals to pursue. The two factors work together to contribute to the discovery of ST at all three levels. MM opens one’s perception to all the hidden meanings in ordinary life experiences—sunsets to sunrises, the starry skies and snow-capped mountains, the spontaneous play of little children and the wrinkled smiling faces of old people—these experiences can move us with a sense of wonder and appreciation of life.

The importance of having a realistic and yet positive worldview is emphasized (Van Deurzen, 2014; Wong, 2021d). Research also indicates that one’s worldview that life has inherent meaning facilitates goal-striving towards sacred emotions (Emmons, 2005) or eudaimonic happiness (Braaten & Huta, 2016). In addition, Haidt (2000, 2003) provides evidence that being open to the possibilities of discovering meaning and connecting with something larger increases the likelihood of awe and positive emotion of elation. Together, these two factors contributing to the pursuit and discovery of self-transcendence, which has four defining characteristics.

The Four Defining Characteristics of Self-transcendence

A Shift in Focus from the Self to Others

This involves a re-orientation from egotistic concerns or selfishness towards something greater or someone more valued than oneself. There is a new sense of selflessness in being connected with something vast or grand or someone more important than one’s own life. While the will to meaning provides the necessary motivation to actively engage in searching for ST, the MM provides the worldview and openness to discover something that transcends selfishness and personal limitations. This re-orientation may happen at three levels: the transpersonal, life as a whole, and situational. At the transpersonal level, there is a perceived connection with God, nature, or all living things. There is a new openness to the spiritual/transcendental realm and the possibilities of meaning, beauty, and goodness all around us facilitates our discovery of all these ideals. At the level of life as a whole, there is an awareness of one’s worthy life purpose or the unconditional self-acceptance and affirmation that one’s life has inherent meaning and value, independent of one’s possessions or achievements. Awareness of major life transitions and one own mortality can shift one’s focus from preoccupation with earthly concerns to the larger schemes of things and the transcendental realm. Spiritual conversion may also shift the focus from the city of the earth to the city of heaven (Augustine, 2009; Tolstoy, 1882/1921).

A Shift in Values

This involves a shift in emphasis from extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to doing something in its own right, such as playing, doing good deeds, or caring for friends and loved ones. Such activities are not only inherently rewarding and worthwhile, but also beneficial to others and make the world a better place. One engages in ST for its own sake, rather than as an instrument to serve some other extrinsic motive. It also entails the willingness to sacrifice self-interest for serving the greater good or higher purpose. Intrinsic motivation also means pursuing some goal that has intrinsic or inherent value—the value that is good in itself and for its own sake, such as the goal of helping others, saving lives, or saving planet earth. William Frankena’s (1973) list of intrinsic value includes life, consciousness, love, virtue, justice, and all things that are morally good inherently. These shifts in focus and values may result from a personal encounter with a life-changing event, such as surviving 9/11 or a serious illness, but also from a shift in perspective from the success orientation to the spiritual or meaning orientation as a result of reading Frankl’s books or seeing a meaning therapist. These shifts emphasize that all people are hardwired for connecting with each other and with a higher power or cosmos; therefore, relational pursuits motivated by love and compassion are deeply satisfying to the extent they meet one’s deepest spiritual needs.

An Increase in Moral Concern

There is increased attention to the moral dimension in one’s goal pursuit and action. The above shifts are aligned with one’s moral compass, which includes one’s innate conscience (natural moral law), religiously or theologically based moral law, and some culturally based normative vision of moral values and virtues. The cardinal virtues according to Plato and Confucius, or the normative ethics of the golden rule, are part of the moral compass that differentiates true self-transcendence from pseudo-ST, such as terrorist suicide bombers. In addition, we are endowed with the capacity for moral reasoning. We evaluate some goals and actions as moral when they are consistent with our moral compass. Moral responsibility is important to ensure that we are sensitive to the wellbeing and rights of other people in our goal strivings and decision makings.

Emotions of Awe

All the above three characteristics may trigger emotions of elevation. These emotions include awe, ecstasy, or amazement because of something extraordinary in its vastness (God or nature), ability (exceptional accomplishment), or goodness (special kindness of one person towards another). This feeling of awe is part of life-transforming experiences because it moves people towards worship or becoming a better and more responsible person.

Peak experiences (Maslow, 1964) and the experience of timelessness in flow (Csikszentmihalyi & Hunter, 2003) often involve the emotion of awe. Watching sunsets, listening to classical music, or worshipping God in a church or temple can all contribute to the emotion of awe. Dobson (2015) provides a thorough review of the literature of awe and concluded that awe is related to a diminished sense of the self.

In a qualitative study, Bonner and Friedman (2011) also identified similar themes in their analysis of participants’ accounts of experiencing awe. Specifically, they found that when participants experienced awe, they described that they were part of something larger than themselves. In addition, the experience of awe was associated with decreased attention to the self. Generally, the emotion of awe contributes to a shift in focus and wellbeing (Rudd et al., 2012) and ST goals (Seaton & Beaumont, 2015). Furthermore, Kristján Kristjánsson (2015) has also examined how awe is related to humility and virtue.

In view of this finer differentiation of four defining characteristics, Wong developed the 24-item Self-Transcendence Measure (STM) with 6 items pertaining to each dimension, which was later revised into 21 items after elimiting items with double-loadings. This revised STM has already been used in a few studies with demonstrate its validity. For example, Dhillon’s (2020) path analysis has empirically supported Wong’s (2017) self-transcendence spiral hypothesis, whcih posits that when there is a clear shift in focus from self to other as measured by STM, there is an increase in “meaning-virtues-happiness” cycle. In another study, Dhillon (2021) shows that STM is negatively associated with depression, but positively correlated with social support, meaning in life and positive-traumatic growth in divorced women. Finally, Singh & Dhillon (2021) reported that in young adults, humanity was the only virtue correlated with STM, whereas in middle aged sample, all virtues as measured by Peterson & Seligman’s (2004) VIA were correlated with STM.

Wong’s Self-transcendence Paradigm

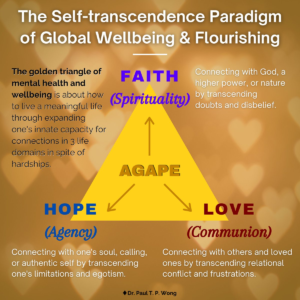

According to Wong’s self-transcendence paradigm (Wong, 2021a), self-transcendence can only be experienced through satisfying the soul’s deepest yearning for connections with ourselves, with others, and with God: the three major life domains, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

The golden triangle of self-transcendence

Frankl (1946/1985) got it right when he said that love is the ultimate truth: “The truth-that love is the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire.” Indeed, the most promising way to live a good life is to aim at the highest ideal of unconditional love (agape) for the self, for others, and for God as shown in the Golden triangle.

This requires a radical reorientation from egotistic concerns to striving for the ideal of becoming one’s best in order to serve others and glorify the source of life and all blessings. Such striving towards the ultimate concern or the highest good will lead to adaptive balance between all opposing forces and result in inner peace and harmony even during COVID-19.

The concept of faith, hope, and love can be grasped intuitively because we all have the innate capacity to believe, hope and love; as well, we all have experienced these human qualities even when we are not fully aware of it. For example, whenever we pledge to marry someone or enter into a business relationship with someone, we are taking a leap of faith because people are complex, and we can never fully know or understand that our partner will be trustworthy or compatible in the future. Similarly, when we are in desperate situations beyond human control, we naturally pray to God or a higher power for help (Goodman, 2020). To protest ourselves against the terror of death, we may unconsciously identify with our cultural beliefs, according to terror management theory (Pyszczynski et al., 2004).

Likewise, hope is also optimistic state of positive expectation, but often related to having confidence in our own efficacy. Whatever our goal or plan, we are motivated to work towards it only when we have some agentic hope of success. According to hope theory (Snyder & Lopez, 2009), hope is defined as the perceived ability to discover the pathways to desired goals and the efficacy to achieve these goals. There is a vast literature supporting hope theory. While faith make all things possible, hope makes the prospect of our future plans brighter, and love connects us all together.

When it comes to love, compassion, and relationships, the literature is beyond measure. Supreme human achievements, from medicine and science to religion and literature, are motivated by love. Some of the best poems and music are inspired by love. There is a very long list of publications on the importance of loving and connecting with others (e.g., Adler, 1938/2011; Ainsworth, 1989; Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Fromm, 1956/2019). There is a consensus that humans are hardwired to connect (Golemen, 2007; Siegal, 2010).

At the personal level, we desire to love and to be loved. Intuitively, we believe that love is the antidote to loneliness, and the key to happiness. A life without love is like a garden without water. We need love in order to satisfy our soul’s deepest yearnings and make our life complete.

In sum, our soul needs faith, hope, and love just as our body needs air, food, and water. When any of these basic psychological/spiritual needs are not met, we will experience a loss of life balance and an increase in distress. In this paper, we tested this hypothesis (see main study) and found that the evidence supports our claim hese three pillars of mental health (or the golden triangle of wellbeing) are capable of not only enabling us to cope effectively with the suffering of COVID-19, but also transforming us into better and stronger human beings.

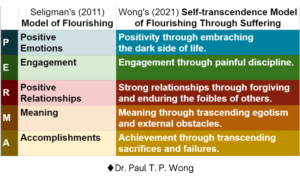

Wong (2021a, 2021d) proposes that the self-transcendence approach to global wellbeing involves so many fundamental changes in assumptions and methodology that it represents a new paradigm of flourishing through suffering. It hypothesizes that all the good things in life are on the other side of fear, and all the best things in life are on the other side of suffering. Therefore, it is difficult if not impossible to achieve flourishing without going though the gates of overcoming adversity as reflected by Figure 6.

Figure 6

Seligman’s (2011) model of flourishing compared with Wong’s (2021a) Self-transcendence model of flourishing through suffering

Figure 6 indicates that only by incorporate the realism of transcending or overcoming the harsh reality of life, can we achieve flourishing, especially in the era of COVID-19, when suffering can no longer be ignored or avoided. Thus, it requires a radically different sets of basic assumptions for wellbeing:

- Everything exists in polarity. The old way of binary either-or thinking is that everything is either positive or negative as two opposite poles on the same dimension. The new way is to see positive and negative as two separate but complementary dimension, thus allowing maximum cognitive flexibility and emotional agility in coping with the world.

- The old way is to choose between one of two opposite poles. The new way is to have a mind big enough to hold two opposing ideas or a heart big enough to hold two opposing emotions. This involves creative tension and creative thinking to transcend the two opposites.

- The old way is to seek to maximize the positive and minimize the negative, to accept one position and reject the opposite one. This will result in polarized mind and a divided society. The new way is to navigate an optimal balance between two opposites to maintain dynamic harmony and balance as the core of wellbeing.

In sum, self-transcendence is the less travelled road towards personal growth and wellbeing. This narrow path will never be as popular as the broad way to happiness because it involves tough choices in favor of what is truth, good, and beautiful, but it will lead you to live a life of meaning and fulfillment.

In the age of COVID-19, when people all over the world are overwhelmed by loneliness, anxiety and stress, the practice of self-transcendence will lead to a more compassionate and harmonious society (Wong, 2016a) and a return to the virtue of humility and selfless love. In short, the self-transcendence paradigm requires a very different way of doing research and intervention to promote global wellbeing.

Development of the Self-Transcendence Measure

The Self-Transcendence Measure (STM) was designed as a psychological instrument to measure ST. The 24-items of the scale (see the Appendix) were generated by Wong primarily based on the four-factor model concept of ST described earlier. The face validity of these items was first screened by a group of 30 graduate students taking a course on self-transcendence and by three psychology professors (co-authors of this scale at the University of East London). The list was then presented to a group of 30 scholars (including philosophers, theologians and psychologists) supported by a Templeton Grant on self-transcendence (Guerra, 2017) for their feedback. Some of the 24 statements were reworded as a result of their feedback as shown in the Appendix.

Factor structure of the STM

Study 1

To examine the factorial structure of the STM, a series of studies was conducted. Participants were recruited using Mechanical Turk (www.mturk.com), which is a web portal that facilitates paying participants to complete tasks such as surveys. Recruiting participants from Mechanical Turk has exhibited comparable research results as more conventional methods; with a diverse participant sample comprising good generalizability (e.g., see Buhrmester et al., 2011). Furthermore, it avoids the problem of using WEIRD samples with a more representative sample (Rad et al., 2018). Participants in these studies were paid varying amounts ranging from $0.40 to $1.50 based on the length of the questionnaire in the study.

An initial exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the 24-item measure using data collected from 240 participants (results from 5 participants were excluded because they did not answer a control question correctly). Of the 235 remaining participants, 138 (58.7%) were male, 96 (40.9%) were female and 1 (0.4%) was other. Their age ranged from 19-73 years (M= 33.76; SD= 10.74); and 193 (82.1%) reported being from USA, 34 (14.5%) from India and 8 (3.4%) from other countries. All reported having English as their first language. A maximum likelihood factor analysis using Promax rotation was conducted and resulted in two factors being retained. This two-factor solution accounted for 43.3% of the variance with the first factor explaining 37.9%. However, this analysis did not yield a clean factor structure. The highest loadings on the first factor were items related to meaning. Several moral items had the highest factor loading on the second factor and some items had dual loadings or low loadings on both factors.

Study 2

The scale items were reduced to 18 of the strongest loading items and a second exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the results from 248 participants (5 were removed due to not answering the control question correctly) who completed this scale version. of the 248 remaining participants, 175 (70.6%) were male and 73 (29.4%) were females. Their age ranged from 19-65 (M = 31.71; SD = 8.30) years old; and 96 (38.7%) were from USA, 134 (54.0%) from India and 18 (7.3) from other countries. English was reported as the first language by 217 (87.5%). A maximum likelihood factor analysis of these 18 items using Promax rotation resulted in two factors being retained. This two-factor solution accounted for 43.1% of the variance with the first factor explaining 37.3%.

Study 3

The scale was further trimmed by eliminating an additional 6 of the original items to produce a 12-item scale that was completed by another 255 participants; 20 were excluded for not answering the control question correctly. Of the 235 remaining participants, 134 (57.0%) were male and 101 (43%) were female; their age ranged from18-72 (M=34.94; SD=10.31) years old. 166 (70.6%) were from USA, 51 (21.7%) from India and 18 (7.7%) from other countries. For 222 (94.5%) participants, English was listed as their first language. A maximum likelihood factor analysis (Promax rotation) was employed to retain two factors. This two-factor solution accounted for 42.8% of the variance with the first factor explaining 35.5%. There were two items that loaded on both factors and were subsequently removed to produce the final 10-item Self-Transcendence-Brief (STM-B)

Psychometric Properties Of The STM-B

Study 4

To examine the construct and concurrent validity of the STM-B, 254 participants were recruited (34 were subsequently excluded from analyses due to not answering the control question correctly) to complete the scale along with the measures noted below. Of the remaining 220 participants, 154 (70.0%) were male, 65 (29.5%) were female and 1 (0.5%) was other. Their age ranged from 20-64 (M=31.37; SD= 8.34) years; and 90 (40.9%) were from USA, 107 (48.6%) from India and 23 (10.5%) from other countries; additionally, 202 reported speaking English as their first language.

In addition to the STM-B, the following measures were completed: The Self-transcendence subscale from the Sources of Meaning Profile-Revised (Reker, 1995), the Collectivism subscale from Sources of Meaning Profile-Revised (Reker, 1995), and the Benevolence and Universalism subscales from the Schwartz’s Value Survey (Schwartz, 1992). The STM-B (M = 29.87; SD = 6.58; N =220) was found to have very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88).

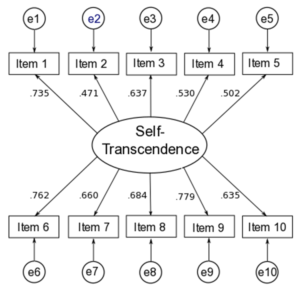

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) in R (R Core Team, 2016) to verify that all STM-B items were indicators of a single latent variable. As the item responses were not normally distributed, the robust estimator maximum likelihood method was used; the results of this analysis indicated that a single factor model provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 45.062, p = .119, N=220; CFI= .978; RMSEA= .036). The results of the CFA are summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Standardized regression weights for the one-factor model of self-transcendence (N = 220)

Note. The models were identified by setting the factor loading of the first indicator of the latent construct to 1.0. The presented values are standardized by setting the variances of both observed and the latent variable to unity.

Table 1

Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations between STM-B and measures of well being (N = 220)

|

|

|||||||

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. Self-Transcendence Scale-Brief | 29.9 | 6.58 | – | ||||

| 2. Sources of Meaning Profile Revised-ST1 | 27.7 | 4.83 | .76 | – | |||

| 3. Sources of Meaning Profile Revised -CS1 | 21.5 | 3.98 | .72 | .76 | – | ||

| 4. Schwartz Value Survey-Benevolence2 | 29.5 | 7.29 | .38 | .35 | .23 | – | |

| 5. Schwartz Value Survey-Universalism2 | 45.9 | 11.09 | .34 | .33 | .23 | .79 | – |

| Note. All correlations displayed are significant at the p < .01 level. 1Reker (1995) 2Schwartz (1992) |

|||||||

Study 5

To examine further the psychometric properties of the STM-B, including test-retest reliability, an additional study was conducted that involved participants completing a package of scales at two points in time.

Time 1. At Time 1, data was collected from 252 participants. There were 29 participants who failed to answer the control questions correctly and were removed from the study. Of the remaining 223 participants, 123 (55.2%) were male and 100 (44.8%) were female. Their age ranged from 18 to 68 years (M=35.4; SD=11.44) and 159 (71.3%) were from USA, 40 (17.9%) from India and the remaining 24 (10.8%) from other countries; also, 211 (94.6%) reported English as their first language.

In addition to the STM-B, scales included at Time 1 were nine measures of various aspects of wellbeing: the Mature Happiness Scale (Wong & Bowers, 2018; 12 items), the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985; 5 items), the Harmony in Life Scale (Kjell et al., 2016; 5 items), the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Watson et al., 1988; 20 items), the Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Wellbeing (Waterman et al., 2010; 21 items), the Peace of Mind Scale (Lee et al., 2013; 7 items), the Objective Life Condition Assessment (Wong, 2018; 1 item), and the Single Item Narcissism Scale (Konrath et al., 2014; 1 item).

The coefficient alpha for the STM-B was 0.87, indicating the internal consistency was very good in this sample and comparable with our previous findings. Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for each of the measures, as well as the correlation between STM-B and each of the other Time 1 measures. STM-B had significant moderate to moderate-high correlations with most of the measures of wellbeing. Interestingly, STM-B had virtually no correlation with the measure of negative affect (PANAS negative scale) or the measure of narcissism (Single Item Narcissism Scale).

Time 2. Of the 223 Time 1participants, 140 (62.7%) successfully completed the Time 2 questionnaire. Of these Time 2 participants, 75 (53.6%) were male and 65 (46.4%) were female. Their age ranged from 18 to 65 years (M=37.2; SD=11.28) and 106 (75.7%) were from USA, 23 (16.4%) from India and the remaining 11 (7.9%) from other countries; also, 137 (97.9%) reported English as their first language.

The Time 2 questionnaire included the following measures also administered at Time 1: STM-B, the Mature Happiness Scale, the Satisfaction with Life Scale, and the Harmony in Life Scale (Kjell et al., 2015; 5 items), and the 15-item Self-Transcendence Scale (Reed, 1986).

The test-retest reliability for the STM-B was high (r =.70, p < .001) over 3-to-4 weeks. The internal consistency of STM-B at Time 2 was also high (Cronbach alpha = 0.88), consistent with our previous results.

The descriptive statistics for Time 2 measures are shown in Table 2. The correlations between the STM-B and the three measures of wellbeing also administered at Time 1 were moderately-high and similar to the Time 1 values. Also, the correlation between the STM-B and Reed’s Self Transcendence Scale was moderately high, providing further support for the convergent validity of the STM-B.

Table 2

Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients of STM-B and measures of wellbeing at Time 1 (N = 223) and Time 2 (N = 140).

| Time 1 | Time 2 | |||||||

| M | SD | r | M | SD | r | |||

| 1. STM-B | 27.81 | 6.88 | 28.32 | 6.98 | ||||

| 2. HILS | 25.85 | 5.98 | .54*** | 25.51 | 6.30 | .56*** | ||

| 3. SWLS | 23.57 | 7.29 | .47*** | 23.26 | 7.59 | .52*** | ||

| 4. M-HAPP | 41.19 | 9.16 | .49*** | 41.35 | 9.34 | .56*** | ||

| 5. PANAS-Pos | 33.02 | 9.13 | .56*** | |||||

| 6. PANAS-Neg | 17.86 | 9.75 | -.08 | |||||

| 7. EWB | 55.21 | 11.71 | .68*** | |||||

| 8. POMS | 24.01 | 5.98 | .45*** | |||||

| 9. R-STS | 31.39 | 8.07 | .65*** | |||||

Note. *** indicates p < .001. M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

STM-B = Self Transcendence Measure-Brief

HILS = Harmony in Life Scale (Kjell, Daukantaitė, Hefferon, & Sikström, 2015)

SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985)

M-HAPP = Mature Happiness Scale (Wong, 2018)

PANAS-Pos = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Positive Items (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988)

PANAS-Neg = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Negative Items

EWB = Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Wellbeing (Waterman et al., 2010)

POMS = Peace of Mind Scale (Lee, Lin, Huang, & Fredrickson, 2013)

R-STS = Self Transcendence Scale (Reed, 1986)

The Main Study: Self-transcendence as a Buffer on COVID-19 suffering

The Purpose of the Present Study

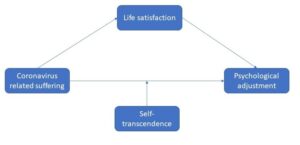

The age of COVID-19 calls for a different approach towards global wellbeing based on overcoming suffering as advocated by existential positive psychology. In the present paper, we first explain what self-transcendence is and why it represents the most promising path for human beings to flourishing through overcome and transform suffering in a complex and uncertain world. After reviewing the literature of a variety of self-transcendence experiences, we first examined the psychometric properties of the Development of the Self-Transcendence Measure (STM) in the previous 5 studies, We now tested a moderated mediation model to explore whether life satisfaction mitigated the negative effect of coronavirus suffering on the psychological adjustment of people and whether Self-Transcendence moderated the mediating effect of it in this association by serving as a buffer against coronavirus experiences (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

Moderated mediation model demonstrating the association between the variables of the study

Method

Participants

Employing a convenience sample and an online survey, the survey was applied to 183 adults, ranging in age between 20 and 84 years (M = 47.55; SD = 13.11). The study comprised of 62% female and 38% male. According to Kline (2015), an adequate sample size should be 5 or 10 times the amount of the parameters in path and factor analysis, and a reasonable sample size is about 150 (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; Muthén & Muthén, 2002). The sample of this study is thus considered adequate for the analyses. The participants were recruited through social media and e-mail within the research team’s affiliated networks. A web-based survey was created using the study measures and demographic questions. Participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the study and were assured that no identifiable personal information was collected to ensure anonymity.

Measures

Suffering during COVID-19

Suffering Measure during COVID-19 (SM-COVID-19) was used to measure the suffering experiences during COVID-19 of people, including their adversity (Wong, 2020b). The scale is a 10-item self-report scale (e.g., “Poor physical health condition”), and all items were scored using a 5-point Likert type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal). The internal reliability estimate of the scale with the present study was strong, see Table 3.

Personal Meaning

The brief version of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP-B) was used to assess individual’s perception of personal meaning and sense of purpose and personal significance in their lives (McDonald et al., 2012). The PMP-B is a 21-item self-report measure (e.g., I believe I can make a difference in the world). Participants indicate their agreement with each item on a 7-point Likert type scale, ranging from 1 (not all all) to 7 (a great deal). The subscales of the PMP-B include achievement, relationship, religion, self-transcendence, self-acceptance, intimacy and fair treatment. The subscale scores can be summed to form a total score. The internal reliability estimate of the scale with the present study was strong, see Table 3.

Psychological Adjustment

Brief Adjustment Scale-6 (BASE) was used to assess psychological adjustment problems, which is a 6-item self-report instrument (e.g., “I nearly always feel awake and alert.”), scoring on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely (Cruz et al., 2020). The internal reliability estimate of the scale with the present study was strong, see Table 3.

Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used to assess people’s cognitive emulations of the life. The scale is a 5–item self–report scale (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”) responding based on a 7-point Likert type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; Diener et al., 1985). Internal reliability estimate with this study sample was strong, see Table 3.

Table 3

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables

| Mean | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | ||

| 1. Coronavirus suffering | 22.62 | 7.33 | .41 | -.40 | .83 | — | –.01 | –.22** | .50** |

| 2. Self-transcendence | 33.56 | 4.83 | -.82 | .59 | .84 | — | .33** | –.20** | |

| 3. Life satisfaction | 24.15 | 6.29 | -.62 | -.04 | .89 | — | –.47** | ||

| 4. Psychological adjustment | 18.22 | 9.39 | .58 | -.77 | .93 | — |

**Correlation is significant at the .001 level (2-tailed).

Data Analyses

Data analyses were performed into two steps. Prior to testing the proposed model, we firstly examined the psychometric properties of the Self-Transcendence Measure (STM) in the present study. The factor structure of the scale was identified using exploratory factor analysis with the sample derived from the previous study (n= 213 [69% male, age range = 19 to 65–M=31.90 and SD= 8.52]; see in the introduction). Factor loading scores (λ) ≥ .40 are recommended for selecting items of the measure (Stevens, 2009; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). After exploring the factor structure of the measure, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to affirm the latent factor structure of the measure with sample of the present study (figure 9). Results from this analysis were interpreted using several model fit statistics and their cut-off scores: non-normed fit index (NNFI ≥ .90 for acceptable fit), comparative fit index (CFI ≥ .90 for acceptable fit), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ .10 for acceptable fit), and the standard root mean square residual (SRMR ≤ .10 for acceptable fit) (Hooper et al., 2008; Kline, 2015).

Figure 9

Confirmatory factor analysis results

Item Legend

Item 1: My life is meaningful because I live for something greater than myself.

Item 2: My suffering is more bearable when I believe that it is for my family, friends, and/or for a higher purpose.

Item 3: I enjoy the process of striving towards excellence in what matters.

Item 4: At my funeral, I want to be remembered as a decent human being who cared about others.

Item 5: A worthy lifelong pursuit ought to have some intrinsic value—something that is good in its own right.

Item 6: What matters most to me in life is the contribution I make to society.

Item 7: I focus on discovering the potential meaning in every situation.

Item 8: I devote my life to pursuing the ideals of beauty, goodness, and truth.

Item 9: I develop my full potential in order to give my best to benefit society.

Item 10:I am more motivated by doing something meaningful than by the prospect of receiving external rewards.

In the second step of the analyses, preliminary analyses were examined including descriptive statistics, analysis assumptions and correlations for the variables of the present study. The assumption of normality was checked based on kurtosis and skewness values and their decision criteria: skewness and kurtosis scores ≤ |1| (Kline, 2015; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Pearson correlation analysis was next conducted to investigate the association between suffering, life satisfaction, psychological adjustment, and self-transcendence. We next conducted a moderated mediation analysis to understand the protective role of self-transcendence on the mitigating effect of life satisfaction in the association between coronavirus related suffering and psychological adjustment problems. The PROCESS macro version 3.5 (Hayes, 2018) was used to employ the moderated mediation model (see Figure 8) with the bootstrapping method with 10000 resamples to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (Hayes, 2018; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The bootstrapping procedure is suggested to examine the significance of indirect effect (Hayes, 2018). All analyses in the present study were conducted using SPSS version 25 and LISREL version 8.80.

Results

Validity and Reliability Analyses of the STM

Results from exploratory factor analysis, which was carried out using principal component analysis with Promax (oblique) rotation, indicated that the measure yielded a two–factor solution with eigenvalues > 1 that explained approximately 58% of the variance and was characterized by a lack of singularity (Bartlett’s χ2 = 854.55, df = 45, p < .001) and adequate sample size (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin [KMO] = .88). The factor loadings of the measure were adequate–to-strong, ranging between .40 and .93. Following, confirmatory factor analysis results affirmed the two–factor measurement model, providing adequate data-model fit statistics (χ2 = 90.89, df = 34, p< .001, NNFI = .92, CFI = .93, RMSEA [95% CI] = .097 [.073, .12], SRMR= .062). The STM also had adequate–to–strong factor loadings (λ range = .44-.69), characterizing by adequate latent construct (H = .75–.77–.86) and internal reliability estimates (α = .73–.76–.84), as seen in Figure. 9. Additionally, the correlation results with the measures in this study provided further evidence for concurrent validity of the measure. These results suggest that the STM is a reliable and valid measure for use in assessing people’ self-transcendence.

Testing the Moderated Mediation Model

We firstly examined descriptive statistics for the variables of the study, as shown in Table 3. Descriptive statistics indicated that kurtosis and skewness scores of the study variables ranged from –.82 to .59, indicating that the measures of this study had relatively normal distribution (Kline, 2015; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Correlation analysis results further revealed that coronavirus related suffering was significantly and negatively associated with life satisfaction (r = –.22, p < .001) while positively correlated with psychological adjustment problems (r = .50, p < .001). However, the correlation of coronavirus related suffering with self-transcendence was non-significant (r = –.01, p = .907). Self-transcendence had a significant and positive correlation with life satisfaction (r = .33, p < .001) and a negative association with psychological adjustment problems (r = –.20, p < .001). There was also a significant and negative correlation between life satisfaction and psychological adjustment problems (r = –.47, p < .001), as seen in Table 3.

We secondly conducted the moderated mediation model testing the protective role of self-transcendence on the mitigating effect of life satisfaction in the association between coronavirus related suffering and psychological adjustment problems. Findings from moderated mediation model showed that coronavirus related suffering had a significant predictor effect on people’s life satisfaction (b = –.20, p < .001) and accounted for 5% of the variance in this variable. Psychological adjustment problems were significantly predicted by coronavirus related suffering (b = .66, p < .001) and life satisfaction (b = –.45, p < .001). These results indicated that life satisfaction mitigated the adverse impacts of coronavirus related suffering on the psychological adjustment of people. Further, the analyses demonstrated that the interaction between coronavirus related suffering and self-transcendence on psychological adjustment problems was significant (b = –.07; F = 16.71, p < .001), accounting for 5% of additional variance in the model, as shown in Table 4. Overall, the model explained 46% of the variance in psychological adjustment problems. Moreover, the simple slope effect revealed that the indirect effect of coronavirus related suffering on psychological adjustment was observed when self-transcendence was high (+1 SD), moderate, and low (−1 SD), as seen in Figure 10. These results indicate the protective effect of self-transcendence on people’s psychological adjustment in during the coronavirus public health crisis.

Table 4

Unstandardized coefficients for the moderated mediation model

| Consequent | |||||||||||

| M (Life satisfaction) | Y (Adjustment) | ||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |||||

| X (Coronavirus suffering) | a | –.20 | .09 | <.001 | c‘ | .66 | .08 | <.001 | |||

| M (Life satisfaction) | — | — | — | b1 | –.45 | .09 | <.001 | ||||

| W (Self-transcendence) | — | — | — | b2 | –.22 | .11 | .057 | ||||

| X×W | — | — | — | b3 | –.07 | .02 | <.001 | ||||

| Constant | iM1 | 24.26 | .45 | <.001 | iy | 28.94 | 2.36 | <.001 | |||

|

R2 = .06 F = 10.74; p < .001 |

R2 = .46; R2 change= .05 F = 34.95; p < .001 |

||||||||||

| Indirect effects of coronavirus suffering on psychological adjustment | |||||||||||

| Coeff. | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||||||||

| Life satisfaction | .09 | .04 | .03 | .17 | |||||||

Figure 10

Moderating effect of Self-transcendence on the link between coronavirus related suffering and psychological adjustment problems

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to test a moderated mediation model examining whether life satisfaction mediate the association between suffering during the pandemic and psychological adjustment problems and whether self-transcendence moderates this association. The results showed that coronavirus suffering was a significant predictor of life satisfaction and psychological adjustment problems, and life satisfaction mitigated the effect of suffering on psychological adjustment. Most importantly, self-transcendence the mediating effect of life satisfaction on the association between suffering and adjustment. Self-transcendence served as a buffering against coronavirus suffering and promoted the adaptive psychological adjustment of people. Recently, the American Psychological Association (2020b) reported a nationwide mental health crisis in 2020 because of COVID-19. However, there is still a silver lining in the dark cloud ahead of us; that is, prolonged lockdown and social isolation also provide a rare opportunity for self-reflection and self-transformation. More specifically, we suggest that learning to accept the current condition, and re-oriented one values and life goals towards something greater than oneself can elevate our lives to a higher plane. Emmons’ (1986, 2003) research on Personal Goal Striving Theory can also account for the connection between ST and wellbeing because some of the worthy life goals, such as spirituality and generativity, are clear examples of ST. Meaning research has demonstrated that ST is a source of wellbeing as we reviewed in the introduction. Future research will clarify the importance of ST in all kinds of happiness, including attunement with oneself, with others, and the world as a fundamental state of happiness and wellbeing (Haybron, 2013; Wong, 2014b).

We suggest that the STM represents an important instrument in advancing second wave positive psychology (PP 2.0; Ivtzan et al., 2015; Wong, 2011) for several reasons. Firstly, it measures a sustainable wellbeing that is less dependent on positive emotions and positive circumstances. Secondly, it shifts the focus from behavior and cognition to the spiritual dimension that really separates human beings from other animals. Thirdly, it acknowledges that ST is the most promising path to moral virtue, eudemonic happiness, and existential meaning. Frankl wants to make sure that a good theory of ST needs to pass the Hitler test—that is, someone like Hitler can never lay claim to have lived a worthy self-transcendent life. That is why he was at pains to emphasize the conscience test, objective values, and ethical responsibility towards others. Similarly, Levinas (1972/2003) also emphasizes that a fully functioning human will transcend self-interest in order to be ethically responsible for the Other.

To attain ST is our crowning humanistic and spiritual achievement, which enables us to move from instinctive selfishness to a state of selflessness and higher level of consciousness. ST motivates people to devote their time and energy to make positive contributions in society, appreciate little miracles everyday life, thus, resulting in greater wellbeing for themselves and others. Costin & Vignoles (2020) reported that a sense of mattering consistently emerged as a significant precursor of meaning in life. Mattering refers to the belief that one’s actions have made a difference in the world and that one has lived a significant life. We propose that such a belief is more like based on living a life of ST, as measured by the STM-B.

It has taken more than 5 years, beginning in Wong (2016c) and involved many researchers from different countries to develop a reliable and valid measure of ST. Consistent with the past literature (e.g., Kaufman, 2020; Yaden, et al, 2017; Wong, 2014c), our series of validation studies have demonstrated that STM-B as a measure of or-orientation our focus and values away from egotism towards others and higher ideals s indeed significantly connected with meaning, benevolent values, virtues, eudaimonia, and mature happiness.

More importantly, we have demonstrated that the STM-B is a buffer against COVID-19 suffering. Thus, we propose that self-transcendence may be a unique antidote to adversity and suffering as well as a pathway towards personal growth and mature happiness. We hope that STM-B can be used widely as an instrument to monitor global wellbeing in the era of the coronavirus pandemic. In sum, Frankl’s concept of self-transcendence adds both depth and breadth to meaning in life and may be an important breakthrough in mental health because it restores the soul or spiritual dimension as the healthy core in overcoming suffering and mental illness.

We realize the limitations of not relying more on prospective or longitudinal studies. Other recent research in the special issue of Frontiers on Self-Transcendence (Wong, Mayer & Arslan, in press) have remedied this deficiency. On the positive side, it provides a useful instrument to study self-transcendence as a spiritual motivation or value.

Everyone is free to pursue what they believe will make them happy, but they are not free from the negative consequences of their choices. Often, the consequence could be the painful regret of hurting their loved ones or getting punishment for their unethical means to achieve their egotistic end.

This paper shows that by re-orienting one’s focus and values from one’s pre-occupation with happiness as one’s main life goal, to selflessly striving towards a worthy life goal that benefits society, it give one a sense of satisfaction from the intrinsic value of pursuing meaning self-transcendence. Interestingly, some Japanese psychologists have developed a Fear of Happiness Scale and Fragility of Happiness Scale (Namatame et al., 2021). Such fear is warranted in view of the avoidable sufferings from blind pursuit of happiness. We hope that the STM-B will contribute the global wellbeing through the less travelled path of self-transcendence.

References

- Ackerman, C. E. (2021, February 18). What is self-transcendence? Definition and 6 examples. PositivePsychology.com www.positivepsychology.com/self-transcendence/

- Adler, A. (1938/2011). Social interest: a challenge to mankind. Martino fine books.

- Aiello, R. (2020). Even if there’s a vaccine, pandemic may persist for years to come: Tam. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/even-if-there-s-a-vaccine-pandemic-may-persist-for-years-to-come-tam-1.5050584

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709-716. Doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709

- Allen, S. (2018). The science of awe. Greater Good Science Center. https://ggsc.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/GGSC-JTF_White_Paper-Awe_FINAL.pdf

- American Psychological Association. (2020a). Self-transcendence. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/self-transcendence

- American Psychological Association. (2020b). Stress in America 2020 survey signals a growing national mental health crisis. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/10/stress-mental-health-crisis

- Augustine. (2009). Confessions (H. Chadwick, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

- Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17, 319-325. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bethelmy, L. C., & Corraliza, J. A. (2019). Transcendence and sublime experience in nature: Awe and inspiring energy. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 509. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00509

- Bonner, E. T., & Friedman, H. L. (2011). A conceptual clarification of the experience of awe: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Humanistic Psychologist, 39(3), 222-235. Doi:10.1080/08873267

- Braaten, A., & Huta, V. (2016). How fundamental worldviews about life and the world relate to eudaimonia, hedonia, and the experience of meaning. Paper presented at the 9th Biennial International Meaning Conference, Toronto, ON.

- Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

- Camus, A. (1942/1955) The Myth of Sisyphus (Trans. J. O’Brien). Hamish Hamilton.

- Clewis, R. R., Yaden, D., B., & Chirico, A. (2021). Intersections Between Awe and the Sublime: A Preliminary Empirical Study. Empirical Studies of the Arts. Doi: 10.1177/0276237421994694

- Costin, V., & Vignoles, V. L. (2020). Meaning is about mattering: Evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), 864–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000225

- Cruz, R. A., Peterson, A. P., Fagan, C., Black, W., & Cooper, L. (2020). Evaluation of the Brief Adjustment Scale–6 (BASE-6): A measure of general psychological adjustment for measurement-based care. Psychological Services, 17(3), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000366