Dr. Paul T. P. Wong’s autobiography, A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith, is published in weekly installments. Stay updated here.

Pui Ching & Life’s Tough Lessons

After graduation from St. Stephen’s as the top student in my class, I was automatically accepted by the best schools in Hong Kong. However, against my father’s will, who preferred an English education for me for a better future, I chose Pui Ching Middle School. There were two reasons: First and foremost, I wanted to learn more about Chinese history and literature because, at that time, I was caught up in a patriotic fever. Second, Pui Ching was indisputably the most prestigious Chinese middle school in Hong Kong.

The Proud Heritage of Pui Ching

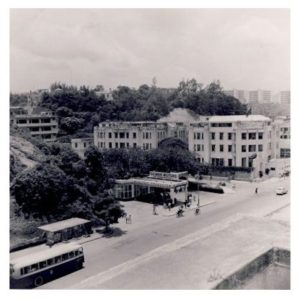

Pui Ching Middle School (Hong Kong) in 1955.

Pui Ching has had a long and distinguished history. It was founded in 1889 in Guangzhou by the Southern Baptist Convention. The Hong Kong branch was opened in 1933 on Waterloo Road, Kowloon.

In 1955, when I graduated, Pui Ching looked like this. In 2016, Pui Ching looked like this. Note that the front section belongs to the Primary School division; now, it has a high-rise building attached to it. The Senior High Section was at the very end of the compass (far left of the photo), probably Block D, which was completed in 1953.

I happened to stumble upon a description of the school scene by an alumnus, written in May 2007. His description was so vivid and accurate that I could not have done any better; I could see myself as one of those youngsters with their heavy backpacks. Therefore, I include the first paragraph of his post here:

Literally hundreds of bespectacled (most of the kids are now) little ones, in their snow-white, spruce, ironed uniforms crossed one of the busiest thoroughfares in Kowloon and streamed into the school ground. Some scrupulously clutched a textbook and others riveted at review handouts—must be exam day. Still others, the vivacious and bouncy kindergarteners and low-graders took strenuous sip of VitaSoy or juice off the paper containers. They were still excited about school as they were yet to be victimized by the rigorous and demanding academic system. (Views, 2007).

Pui Ching Middle School (Hong Kong) in 2016.

Pui Ching’s academic reputation was built on a solid record of achievements by its students and alumni. In my days, Pui Ching was beyond question the best school, according to the School Leaving Certificate Exams administered by the Department of Education of Hong Kong government; year after year, it had the highest average for any school, and no Pui Ching student ever failed the public exam.

Most of the graduates from Pui Ching went on for further studies overseas. Many of them became world-renowned for their achievements. According to Wikipedia, notable alumni include Daniel C. Tsui (崔琦), Nobel Prize Laureate in Physics (1998), and Shing-Tung Yau (丘成桐), a mathematician who was awarded the Fields Medal (1982).

The class of 1955 alone boasts of many stars in different fields. The following three are just on top of a long list of accomplished individuals, according to Wikipedia:

- Alfred Y. Cho (卓以和), the father of molecular beam epitaxy and quantum cascade lasers and former Vice President of Semiconductor Research at Bell Labs, awarded the US National Medal of Science in 1993 and the US National Medal of Technology in 2007 and later inducted into the US National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2009.

- Chia-wei Woo (吳家瑋), the founding President of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

- King-fai Chung (鍾景輝), the first Dean of the Hong Kong Academy for the Performing Arts who earned the Bronze Bauhinia Star; he has been featured in many movies from Hong Kong.

Pui Ching’s success was not accidental; it was unapologetically elitist. It admitted only good students and graduated only the best. For example, for my graduating class of 1955, we began with eight classes at Grade 10, but ended up with only four classes in Grade 12. Each year, weak students were weeded out.

Another factor was that Pui Ching only hired the best teachers. For example, my Grade 7 math teacher was a famous mathematician because of his academic publications; a couple of years later, he was recruited by the University of Hong Kong as a math professor. I was also fortunate enough to have Lo Kang Lei (羅康烈) teach us Tang Poetry.

Mr. Lo was a widely-acknowledged authority on Tang Poetry and the author of a scholarly review book on Tang Poetry (詩詞曲論文集: 古典文學研究叢書). Even though he made us memorize long poems—such as “Song of the Pipa Player” by Bai Juji and “The Legend of the Peach Blossom Valley” by Wang Wei—I still loved him and even now remember him with great fondness. He inspired and moved us by reciting these poems himself with such eloquence and theatrics, his voice going up and down and his upper body waving rhythmically as he performed with his eyes half closed. Now, I still like to make those poems come alive as he did before the class. I have also learned from him that teaching is performance; that has made me an effective teacher.

I had many other memorable teachers. My chemistry teacher, known to students as Chemical Cheung, often gave us surprise quizzes. His famous saying was, “Treat ordinary time as exam time, treat exam time as ordinary time.” (平時當戰時,戰時當平時). As a result, we were always in a state of readiness for testing, a mindset which eliminated the need for cramming before final exams.

I had no problem managing Pui Ching’s academic demands, especially for the endless math assignments. (In senior high, we already covered university-level maths, such as calculus and linear algebra.) In fact, I did so well academically in Grade 8 that I was allowed to skip Grade 9 and went straight to Grade 10. I admit that I had built a solid academic foundation, but my most valuable lessons during those years at Pui Ching were learned outside the classroom.

Lesson on the Transiency of Life

An orchid tree in Hong Kong.

When I was in Grade 7, my classroom faced a square courtyard with a tree that bloomed with purplish-red flowers. I thought that it was an orchid tree because the flowers bloomed in the first semester and withered at the end of March.

During class time, I had the habit of looking out at the orchid tree and sensed with sorrow the unstoppable marching on of time. When the tree bloomed again, I knew that I would be in a higher grade with a different teacher and different classmates. This keen awareness of the fragility and impermanence of life has always been a core value for me since childhood, motivating me to value every passing moment.

My form teacher for Grade 7 was also a biology teacher. Therefore, my classmates gave her the nickname “Cell Woman” (細胞婆). She was very different from Miss Lam, my Grade 6 teacher from St. Stephen’s, who always carried herself in a very gentle and graceful way like Aubrey Hepburn or Grace Kelly and also possessed their quiet and wholesome beauty.

Audrey Hepburn

Grace Kelly

In contrast, Cell Woman was a high-energy young woman who wore make-up and colourful clothing. She walked quickly and talked rapidly with a raspy voice and large gestures. She always came to the classroom in a hurry, as if she were riding on the wind. As soon as she got inside, she would unload all her books on the desk and take a deep breath.

It was amazing to me how she could walk so fast while clutching several books, even when she was six or seven months pregnant. My last image of Cell Woman was her rushing straight into a headwind across the courtyard with her red shoulder-length cap flowing in the air; I am not sure how much of this image was based on my actual memory of her, and how much of it was based on the comic book superhero, Wonder Woman.

When I returned to school for Grade 8, I learned the horrible news that, during the summer, Cell Woman had died from childbirth!

My grief over the loss of Miss Lam was now compounded by the loss of Cell Woman through death. In my young mind, such painful losses cast a pall over all close relationships. If partings, losses, and deaths were inevitable aspects of life, maybe I would be better off remaining single. This might be one of reasons why I never dated anyone in high school or college. My practice of non-attachment served as a defense mechanism for me—I still felt like a misfit, an outsider without a secure home or motherland.

Lesson on Fighting for What One Believes

Being a loner, I never had many friends, but, somehow, I have always managed to attract a few individuals who share my interest. While in Grade 8, I got to know a classmate who also liked painting. On weekends, we often went out to the countryside to paint landscapes.

On one occasion, after we got back by bus, we were swarmed by four or five tough-looking guys. They started picking on my friend, maybe because he had such a “sissy” look. Almost as a matter of reflex, I said: “Please leave my friend alone.” Then, they turned to me and laughed out loud, “Who are you?” “I am a student from Pui Ching,” I answered matter-of-factly. After a quick exchange of an evil look among themselves, they started attacking me with their fists and feet. My iron fist was no match for these gangsters’ street fighting style; soon, I collapsed on the street with blood oozing from my mouth and nose. All this while, my friend just stood there with a shocked look on his face.

When I eventually got home, I discovered that my face was partially covered by purple-colored bruises. I had indeed taken a bad beating, but I did not feel defeated, because it was not a fair fight.

The next day, after school, I noticed the same guys hanging around just outside the school’s main entrance. I suspected that they were gangsters from the nearby Mong Kok. What did they want from me? I had no money and I did not belong to any rival gang. I decided to hide inside the school until these gangsters were gone. This went on for about three or four days until they stopped looking for me.

In hindsight, it may not have been wise for me to step into such a messy situation, but that was simply my natural response. I did not intend to be a hero, but I instinctively wanted to protect my friends and family, even if it meant putting myself at risk.

In my lifetime, I have repeatedly learned the lesson that it is better to stand up and fight for what I believe in than to run or surrender. Even when I fight and lose badly, I still have my integrity and dignity intact. Even a failed attempt still fills my life with meaning, because by my attitude of defiance and my act of courage, I have declared that there is something worth living and fighting for.

Lesson on the Vicissitudes of Life

After St. Stephen’s, we moved to a much more spacious apartment with an ocean view on Chatham Road South, in a quiet residential neighborhood near the tip of Tsim Sha Tsui. Father spared no money and no effort in decorating the new apartment, his newfound pride and joy. In addition to buying expensive furniture, he also acquired original oil paintings and had bookshelves lined with hardcover English books for decorative purposes. He continued expanding his collection of crystal glasses, vases, and ornaments in his curio cabinet.

For almost three years, we lived in luxury. On weekends, we visited places frequented by tourists and ate in high-end restaurants. Apparently, his new businesses in Hong Kong had begun to pick up steam.

Unfortunately, with the end of the Korean War in July 1953, our fortune took a nosedive. With truck tires worth millions of dollars stuck in a warehouse in Macau, due to the Chinese government refusing to pay for tires they no longer needed, we faced a severe cash flow problem.

My Third Uncle, who Mother never trusted or liked, came up with a very risky idea—collecting insurance money. One day, he went to Macau, checked into an expensive hotel, and personally witnessed the burning down of a warehouse. But his celebration did not last long, because the Chinese insurance company disputed the claim, and Third Uncle was arrested for engineering the arson. He was sentenced to 20 years in jail.

As a sequel to the infamous arson case, a bulky man came to our apartment one afternoon and blackmailed us for more money for his involvement in the setting the warehouse ablaze. He was an ex-Nationalist soldier who had lived a life of crime. When he threatened Mother with physical violence, I had no choice but to take on someone who was double my weight. I jumped onto his back, grabbed hold of his neck with my left arm, and punched his face with my iron fist. Meanwhile, Mother called 911. When the police officer arrived at the scene, the ex-solider accused me of attacking him. The police just shook his head with an incredulous look on his face and then arrested him for home invasion.

For the first time, we were literally left penniless. Every day, we witnessed more creditors coming into our apartments and taking away another one of my father’s prized possessions. I will describe our new life in poverty in my next chapter.

Lesson on Accepting my Limitations

My teenage days seem a long, long time ago, but I don’t remember having ever rebelled against authority just for the sake of asserting my independence. Perhaps, I was just too busy pursuing my interests to have the time and energy to challenge adults.

I am grateful that during my junior high years, Father paid for my arts and violin lessons. I went to a vocational arts school to learn the basic techniques of drawing. The school was located in a poor and unsafe area. I had to get through homeless beggars in order to climb a dark, narrow, and creaky wooden staircase to reach the studio on the third floor. When Father learned about my safety concerns, he decided to hire one of the teachers in the arts school to tutor me at home.

I started with charcoal drawing, then watercolor, and finally moved onto oil painting. My two younger brothers Constant and Giles later joined me. After two years, our teacher gave us his assessment about our progress and potential. When he announced that Giles was most talented and I the least, in spite of the fact that I was the oldest and had received the most training, it was very painful to hear. But history has proven him right. Giles later demonstrated his artistic gift in designing his own line of furniture, but I was fired as an illustrator for a children’s magazine.

My pursuit of violin did not fare much better. I was highly motivated and practiced almost two hours a day. I developed calluses on my left fingertips and began to walk with my left shoulder higher than my right shoulder. Yet, in spite of my love for violin and my dedication to mastering it, I was not able to pass a piece of technically demanding concerto.

Week after week, I struggled, but I just could not stretch my figures to play double stops on my violin. My left hand was simply too small to press two notes one octave apart simultaneously. That piece required me to play numerous double stops. Since I already had financial difficulty paying for my violin lessons, it was not difficult for me to give up on this pursuit.

Looking back, these setbacks were actually good things for me. First, I learned to accept my limitations without any bitterness. At that time, I could console myself that I still excelled in both English literature and Chinese literature at school. Second, my limited exposure to painting and violin has greatly enriched my life. My joy in looking at the paintings of post-impressionist artists—such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Paul Gauguin—is still with me. My delight in listening to Jascha Heifetz, Yehudi Menuhin, and Isaac Stern remains. My limitations have not prevented me from fully enjoying the beauty of paintings and music all through my adult life. Indeed, Viktor Frankl was correct in recognizing the experiential value of the arts.

Lesson on My Inner Struggles

My heart was pounding and racing. With every invitation from the evangelist giving the altar call, my heart pounded even louder. “This is the last call, don’t miss the opportunity to receive Jesus into your heart. Now is the time of salvation. Just come forward now; we are not waiting any longer,” the evangelist made his final appeal.

I felt a strange force pulling me to my feet, but held on tight to the metal folding chair with both my hands to ensure that I was not overcome by the powerful emotional force.

In every evangelistic meeting at the school, I went through the same spiritual struggle. In retrospect, I know that God has been working in my life since the St. Stephen’s days. Probably the main reason why I resisted the call with all my might was pride and self-righteousness.

By all objective standards, I could be considered a very ethical and kind person. Ever since I was a child, I had the noble aspiration to be a saint. I practiced Confucius filial piety and the Buddhist teaching of compassion and non-attachment. I constantly gave whatever money I had to beggars. I always found opportunities to help others. I thought that I probably had a higher moral standard than many so-called Christians. As I studied the Bible, which was a required subject at Pui Ching, I could always find something inconsistent or unscientific, and the Bible teacher could not give me a satisfactory answer.

During my last year in high school, I decided not to attend the annual evangelistic meetings, when all the classes were cancelled and all students were required to attend. I found myself sitting in the classroom all by myself, prepared to face whatever penalty the Dean might mete out on me. I made this decision because I was afraid that in my last year, I might finally yield to the strange power of the altar call.

But God did not let me get away so easily. Before the last day of class, a tall classmate with a smiling face (I will call him Brother Chan) invited me to visit the school’s Christian fellowship. Since he was always very kind to me, it would have been rude for me to turn him down, even though I had never accepted any invitation to take part in any social parties or school events.

The fellowship meeting took place in a classroom. There weren’t any adults involved. Brother Chan briefly introduced me to the group (about 30 students), which was followed by a brief time of sharing testimonies and prayer requests. Most of the time was spent in prayer. I had never experienced something so powerful. The students prayed and praised God with such fervor and earnestness that I could feel God’s presence descending on us. I was in a state of awe and amazement.

At the end of the fellowship meeting, I went home a somewhat changed person. I did not see God, but I had experienced him in a quiet and intimate way that was very different from the emotional pressure at evangelistic meetings.

Surprising, how I have benefited most from Pui Ching was not in the academic training, but the spiritual cultivation. Perhaps, Pui Ching’s most important contribution to education lies in the area of Christian faith and character development.

The Spirit of Pui Ching Lives On

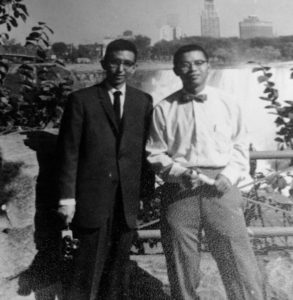

Two or three days after my arrival in Canada, Pui Ching alumnus Joeman took me to Niagara Falls. I did not know him personally because he graduated one year ahead of me. Somehow, through the Pui Ching alumni, he learned about me coming to Toronto, found out where I lived, and invited me to visit Niagara Falls. I was concerned because I did not have the money to travel; he just assumed that he would take care of all the expenses.

Joeman with Paul at Niagara Falls.

We had a wonderful time at Niagara Falls, but I had so many burdens on my mind that I could not give my full attention to the spectacular scenery. I was very moved by his kindness and generosity. I did not have too much contact with him after this memorable trip. Later, I learned from my brother-in-law Geoffrey that he gave up his career as an engineering professor and became a pastor. Joeman epitomizes the spirit of Pui Ching.

Recently, I have been attending the fortnightly reunion luncheon. It is sad to see the attendance decrease each time due to sickness or death. When we get together, health issues seem to be the main topic.

There are Pui Ching alumni associations all over the world. In Ontario, we have more than a thousand alumni, most of them residing in the Greater Toronto Area. We had a Diamond Anniversary (60 year) celebration in Toronto in 2015, attended by about 60 people. Here is a photo with three of my classmates: (from left to right) my brother-in-law Geoffrey Cheung, Alice Chan-Yip, MD, OC, and David Chui, MD.

I am so glad that I am a member of the International Pui Ching Family. My sense of belonging has not diminished over 60 years. My only prayer is that they can still maintain their strong Christian tradition in Hong Kong under the Communist regime.

A table at the 2015 Pui-Ching Diamond Anniversary Banquet in Toronto. From left to right: Geoffrey Cheung, Alice Chan-Yip, Paul, and David Chui (Sept. 28, 2015).

References

- Views, M. (2007, May 31). So nailed it. A guy’s Moleskine notebook. Retrieved from https://mattviews.wordpress.com/2007/05/

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2017). Pui Ching and life’s tough lessons. A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith (ch. 15).

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.