Dr. Paul T. P. Wong’s autobiography, A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith, is published in weekly installments. Stay updated here.

The Nanjing Massacre

1937 was an unforgettable and dreadful year in Chinese history. In that year, Japan launched a full scale invasion of China and committed the Nanjing (Nanking) massacre—the forgotten holocaust of World War II.

I did a Google search for images of children born in 1937. Among hundreds of very disturbing images, I found this photo of a wounded baby crying alone in a devastated train station. He represents hundreds of thousands of little children who were either killed, injured, or orphaned in that year alone. I can still hear his desperate cry and feel his pain and fear—a helpless baby in a hostile world! I wonder how much more suffering he had to endure and whether he even survived the war.

I am most fortunate and grateful that I am still alive, but I carry with me the burden of all these suffering children and vow that I will do everything within my power to make this world a better and safer place for the generations to come.

Another disturbing photo from my Google search is that of refuges, both rich and poor, fleeing from Shanghai before the advancing Japanese Imperial Army. This photo has special meaning because my wife’s parents were among the refuges fleeing from Nanjing prior to the massacre.

Another disturbing photo from my Google search is that of refuges, both rich and poor, fleeing from Shanghai before the advancing Japanese Imperial Army. This photo has special meaning because my wife’s parents were among the refuges fleeing from Nanjing prior to the massacre.

That year, on December 13, the Japanese army entered Nanjing and started a six-week long killing orgy. More than 300,000 innocent civilians and unarmed Chinese soldiers were slaughtered in brutal ways—beheaded, burned, or buried alive. More than 20,000 women and girls were raped. No resident in Nanjing was untouched by these bloody atrocities.

Several years ago, while speaking at a conference in Nanjing, I was able to visit the Nangjing Massacre Memorial Hall (Qīnhuā Rìjūn Nánjīng dàtúshā yùnàn tóngbāo Jìniànguǎn). It is located in Jiangdongmen, one of the execution sites and mass burial places of the massacre. On one of the grey marble walls, the number of victims from the massacre can be clearly seen.

Several years ago, while speaking at a conference in Nanjing, I was able to visit the Nangjing Massacre Memorial Hall (Qīnhuā Rìjūn Nánjīng dàtúshā yùnàn tóngbāo Jìniànguǎn). It is located in Jiangdongmen, one of the execution sites and mass burial places of the massacre. On one of the grey marble walls, the number of victims from the massacre can be clearly seen.

Inside the Memorial Hall, there were exhibits of historical documents, artifacts, photographs, and artworks. The following oil painting by Zi Jian Li (1992), The Great Nanjing Massacre, best captures the horrors of that event.

Journalist Iris Chang has put together a vivid recount of this horrendous event in her 1997 award-winning book, The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II.

Impact of the Nanjing Massacre on My Approach to Life and Psychology

It still troubles me deeply that human beings are capable of such atrocities against their fellow human beings. Even the wildest beasts would not commit such heinous acts! How can we fathom the vileness of human depravity? Who can penetrate the heart of darkness? How far will human evil go when it is unfettered and unconstrained by civilization? We can explore the outermost mysteries of the cosmos and reveal the innermost secrets of the atoms, but we cannot understand or contain the dark side of human existence!

It still troubles me deeply that human beings are capable of such atrocities against their fellow human beings. Even the wildest beasts would not commit such heinous acts! How can we fathom the vileness of human depravity? Who can penetrate the heart of darkness? How far will human evil go when it is unfettered and unconstrained by civilization? We can explore the outermost mysteries of the cosmos and reveal the innermost secrets of the atoms, but we cannot understand or contain the dark side of human existence!

The United Nations powerlessly watched the genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, the Congo, and Syria. Innocent people continue to be tortured and slaughtered in large numbers in various parts of the world. No evil is as monstrous, heinous, and obscene as war. No words or pictures can fully capture the depth and horror of the human suffering inflicted by wars. Yes, nothing and no one can stop wars.

That is why, to me, the biggest challenge of positive psychology is how to transform the baser instinct of human aggression and domination to cooperation and compassion. If we don’t find ways to live in peace, sooner or later war will destroy all of us. Maybe the only hope of preventing such human tragedy is to cultivate a culture of compassion and an unconditional love of life. Love is more than a high-sounding word; it is the only antidote to hate and the best assurance of human survival as a species.

So many of my friends in positive psychology have no problem believing that life is good and that one can easily choose to be happy by doing certain simple activities. Yet, they have difficulty believing that life has intrinsic meaning and value. For me, just the opposite is true. I have difficulty feeling good or happy about life because of the reality of violence, atrocities, and injustices. But I have no difficulty believing in the intrinsic meaning and value of life. Such belief reflects a deep and unconditional reverence for life—the foundation for compassion and love.

If I have to believe in something, I would rather believe in something that is consistent with my nature and makes it easier for me to embrace life in its totality, and then move forward with forgiveness, hope, and joy.

Born to Be an Ox

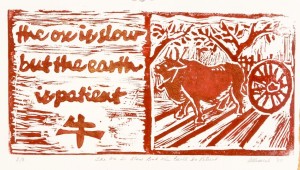

I proudly declare that my nature is that of an ox. According to the traditional Chinese calendrical system, there are 12 animals representing each year of the 12-year cycle, with each animal representing certain personality traits. As I was born in the year of the ox, this is yet another significance attached to the year 1937.

I proudly declare that my nature is that of an ox. According to the traditional Chinese calendrical system, there are 12 animals representing each year of the 12-year cycle, with each animal representing certain personality traits. As I was born in the year of the ox, this is yet another significance attached to the year 1937.

I don’t believe in horoscopes or the Chinese Zodiac, but I gladly embrace the ox as my identity and emulate all its attributes of endurance, tirelessness in hard work, and willingness to serve.

Out of curiosity, I recently did a quick Google search about the characteristics of an ox according to the Chinese Zodiac. I was surprised to discover the description of the “ox people” as dependable, honest, caring, hardworking, and capable of enduring any amount of hardship without complaint.

How apt! I consider myself a draft animal used to pull heavy loads or plow the land. All my life, I have worked like an ox, eager to serve others faithfully without expecting anything in return. When people ask me, “Why are you still working so hard in your old age?” My standard reply is, “Well, that is my destiny, my fate, because I was born to be an ox.”

To identify with an ox simply gives me some insight about suffering and fate. It helps me understand the subtle but profound difference between being born into adversity and being born for adversity. To be born into adversity is to be thrown into an absurd and hostile world that is devoid of ultimate meaning. Like helpless orphans, we are cast into an ocean of suffering, leaving our fate to blind chances. To be born for adversity is predicated on a very different understanding of life. It affirms that life has inherent meaning and purpose regardless of circumstances.

From this perspective, I think God may call someone to a life of suffering in order to achieve a special mission. For example, Jesus was born in a manger fit for animals, and he was crucified as a criminal. But through his sacrificial love and death, he gives us the way of redemption.

I feel privileged to have been chosen for adversity and a higher purpose. I have learned that suffering is not something to be avoided and blessing is not something to be pursued. To live is to embrace the harsh elements and work with one’s own plow, no matter how inadequate. To live fully, one needs to develop the attitude that living with difficulties and deprivations maybe an inevitable part of pursuing one’s calling.

The image of an old ox plowing the field fills my heart with inspiration. The ox has learned to be content to work with its lot—a tiny parcel of parched land and an old rusty plow. Its ribs bulge out from its body, and its skinny legs are shaking, but the old ox struggles to push forward. It works hard under the scorching sun and it works hard through the thunderstorm: Nothing can stop it from doing its job. One day, the small piece of land will yield an abundance of crops that can feed many hungry people. The old ox must feel happy.

Life Under Japanese Occupation

Tianjin did not suffer the same fate as Nanjing, but it was not immune from the atrocities committed by the occupying forces and their Chinese collaborators. Many people were arrested or killed. My family was fortunate as we were simply forced out of our house by Japanese soldiers, but this was nevertheless a traumatic event, one which I will discuss in a later chapter.

Children are extremely resilient. They live in a world of innocence and possibilities even when they are daily surrounded by the reality of evil and cruelty. They are blessed with the special gift to discover fun in the midst of suffering.

From my perspective as a child, daily life under Japanese occupation seemed quite normal except for some inconveniences and fears. For example, as children we seldom ventured out of our door because of the persistent warning that we might be kidnapped to be used for medical experiments (subsequent historical research has substantiated these warnings).

Another inconvenience was the during the later part of the Second World War, when all our windows were taped by newspaper strips and at night we had to use kerosene lamps for fear of bombing raids from the Allied forces. From time to time, sirens would blare out.

During those long evenings, I used to entertain myself by looking at the dancing shadows on the ceilings and the walls, as the tiny flame inside the lamp gently moved. We also entertained each other by using our hands to project different animals on the wall. Imagination was our only source of distraction from the boredom.

Generally, I never felt safe whenever I saw Japanese soldiers with their rifles and Sun Flags in the streets, because of their reputation of treating Chinese people as if we were insects or animals. However, one day, while riding on a train with my parents, a Japanese officer sitting right across us smiled and waved me to come over.

With my parents’ encouragement, I gingerly nudged close to him. He patted my head gently and spoke to me in Chinese: “How old are you?” “I am six,” I whispered. “Well, I have a son your age. He is in Tokyo with his mom.” While listening to his story about his son, I cast a wary glance at his long samurai sword. He offered to me his sword for a closer look and placed my hand on the handle, which had an intricate design.

I do not remember how I felt when I touched the instrument of death. But what a meaningful moment rich in symbolism—the surrendering of a killing machine to an innocent child’s hand! Upon reflection of this friendly encounter with the enemy, I realized that deep down we all share the same humanity.

Overall, the only lasting adverse impact of the Japanese occupation on me physically was malnutrition, although I did not realize this until much later. My mom often said that she felt very bad that I did not have proper nutrition because of the shortage of food and the difficulty of finding a nǎimā, literally, a “milk-mother” or a wet-nurse. In those days, this referred to a woman, typically from a poor village, who sold her own milk to another family after nursing her own baby.

One of the effects of malnutrition was that I had a sunken chest, of which I was very ashamed for most of my adolescent years. My skin problems are also related to nutritional deficiency. When I was a child, my body was often covered with rashes, boils, and scabs. My skin problems still persist and they often remind me of Job’s suffering in the Bible.

Am I Lucky or Unlucky?

Even though I don’t believe in astrology or Zodiac charts, I have often said that when I was born, the stars must have aligned wrongly. This seems an easy way to explain my hard fate. Many born in China in my generation might have felt the same way about their difficult lives. It is not easy to be born in a war-ravaged country during a tumultuous time of history. We all bear the mark of the place and time of our births; we all wear the scars of our nation’s wounds.

The Nanjing massacre represents the worst barbaric and humiliating act since the cession of Hong Kong to Britain in 1841, which initiated a century of humiliation in the hands of foreign powers. The shameful chapter that was Japanese occupation was followed by a civil war, Chinese involvement in the Korean War, and many years of bloody political campaigns in mainland China, culminating in the self-destructive Cultural Revolution. Millions of innocent people lost their lives during those tumultuous years. Millions more have been touched by these tragic losses. The Chinese psyche is yet to fully recover from all these upheavals.

I don’t think that military and economic strength is the antidote to China’s wounded national pride. I would rather like to see a renaissance of Chinese culture that has enabled us to survive more than 5,000 years as a nation, in spite of all the foreign invasions and civil wars. If we have learned anything from all the costly, bloody wars in modern times, it is that dictatorship and nationalism pose the greatest threat to peace, both nationally and internationally.

I am increasingly convinced that the best way to achieve world peace is to believe in the intrinsic value and meaning of all life and to unconditionally love all people regardless of their nationality, religion, or ideology. Such a vision of universal brotherhood gives us the best chance at survival.

In hindsight, I am glad that I was born a war baby in China and have inherited the Chinese DNA of endurance. My calling may have been incubated in my mother’s womb. I might not have become a messenger of hope and joy to suffering people had I been born in a different country and in a time of peace and prosperity.

References

- Chang, I. (1997). The rape of Nanking: The forgotten holocaust of World War II. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Li, Z. J. (1992). The great Nanjing Massacre [Painting]. Nanjing, CN: Nangjing Massacre Memorial Hall.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.