Submitted by Ken Howard, M.Div., M.Ed., for the Positive Living Newsletter (May 2017). Read the rest of the newsletter here.

In both my first career in human and organizational development, and my second career in ordained ministry and the formation of faith-based communities and organizations, a large part of my work has centered on the role that transcendent meaning plays in individual motivation and the development of organizational culture.

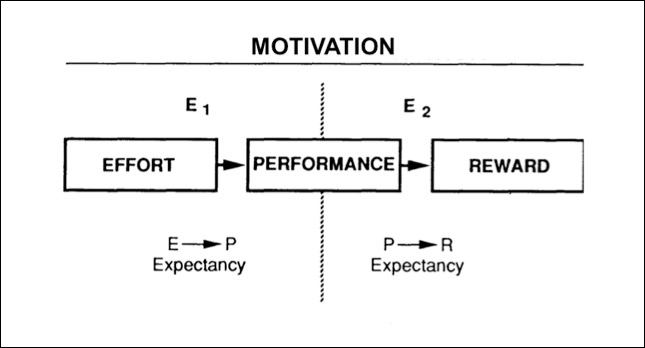

In the late 1980s, I published an article in Adult Education Quarterly, entitled “A Comprehensive Model of Expectancy Motivation.” The intent of this article was to provide a more complete understanding of what motivates individual learning in an organizational environment by describing how personal meaning affected learning motivation.

At the time of the article’s publication, prevailing learning theories viewed learning motivation largely as a mechanistic response to external rewards. Some had gone as far as to include the valence (i.e., value or meaning) of the reward to the learner. Yet none had proposed approaching it in a more organic and systemic way.

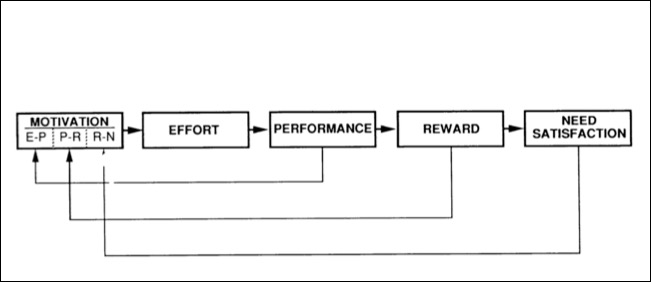

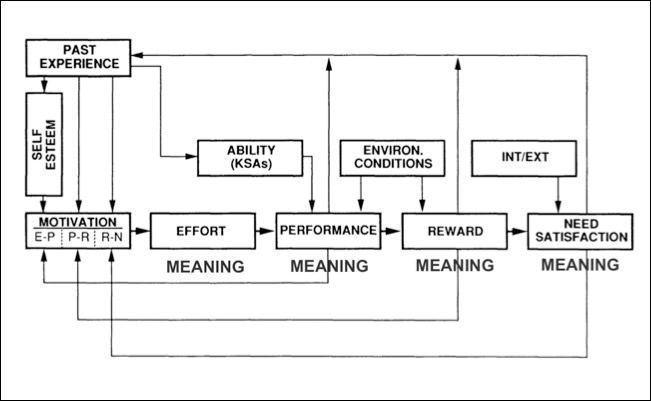

My article set out to develop a more holistic model in several ways: by adding a Need Satisfaction component, by describing it as a cyclical process in which actual achievement informed internal motivation, and by describing it as an open system with many pre-existing and external factors that also influence an individual’s motivation to learn. In this model, Meaning influences almost every aspect of learning motivation; not just the meaning individuals attach to Reward, but also to Effort, Performance, and Need Satisfaction.

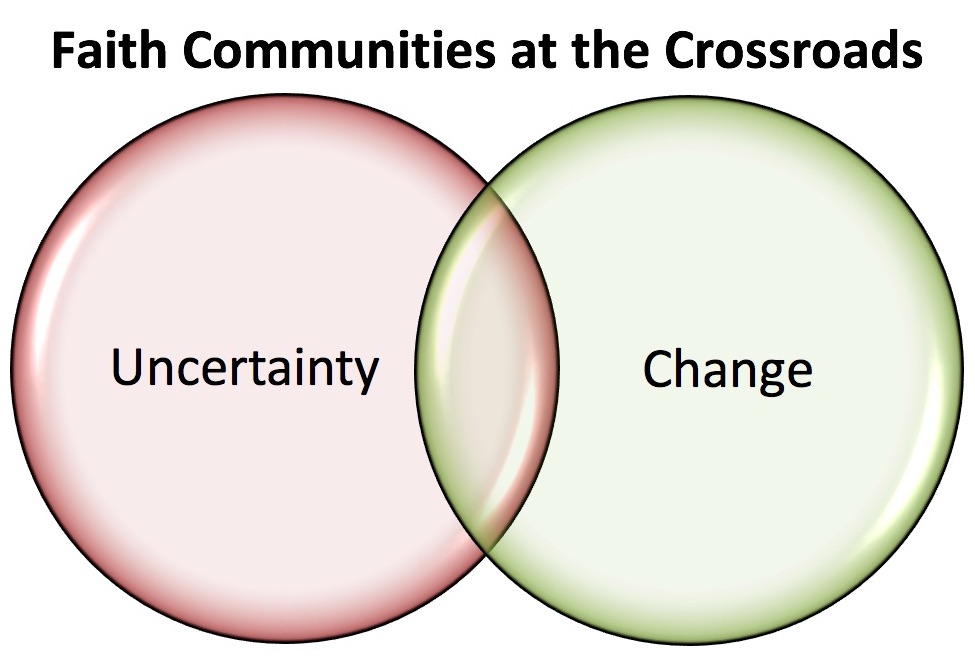

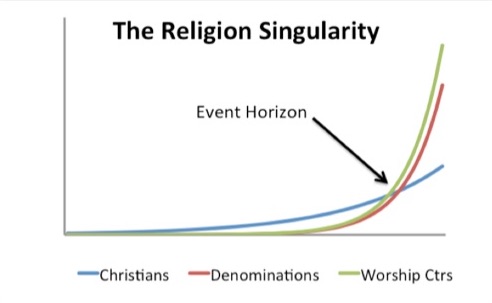

Since 2010, and the publication of my book, Paradoxy: Creating Christian Community Beyond Us and Them, I have been exploring the role of meaning from an organizational perspective, specifically, how it functions in faith-based communities and organizations operating in environments of high uncertainty and rapid change. In my soon-to-be published research article on demographic trends within the denominations and worship centers that comprise Christianity, I describe a runaway expansion of those organizations at a rate of growth considerably higher than that of the overall Christian population.

This differential is driving down the average number of Christians per worship center and denomination to levels that will become unsustainable before the end of the century. Leaders are faced with the dilemma of how to rapidly adapt to changing conditions without losing sight of the vision that sustains their existence. To help leaders of faith-based communities and organizations navigate these turbulent times, I have offered for consideration a practice I call Vision-Guided Experimentation (VGE). VGE is a two-part process that involves both visioning and experimentation.

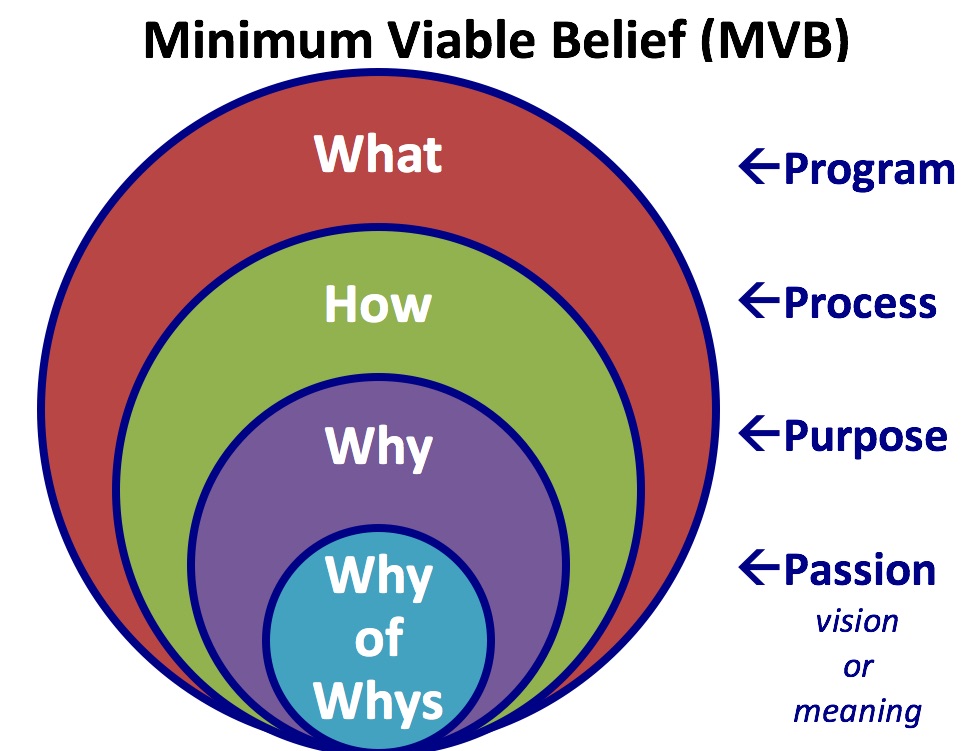

The visioning part of VGE I call Minimum Viable Belief (MVB). A faith-based community’s Minimum Viable Belief is its overarching vision: the single motivating meaning or “Why of Whys” that lies at the heart of every other purpose, process, or program of that organization—the source of passion for all who participate in that community. Research and experience have taught me that the greater the number of beliefs or practices a faith community requires for membership, the greater the likelihood the organization will disintegrate. However, the fewer and more overarching the beliefs or practices, the more motivated, flexible, self-guiding, and enduring the community will be. MVB is to a faith-based community or organization what the North Star once was to sailors at sea: a way to stay focused in the right direction and oriented toward your ultimate vision, no matter which way the winds blow.

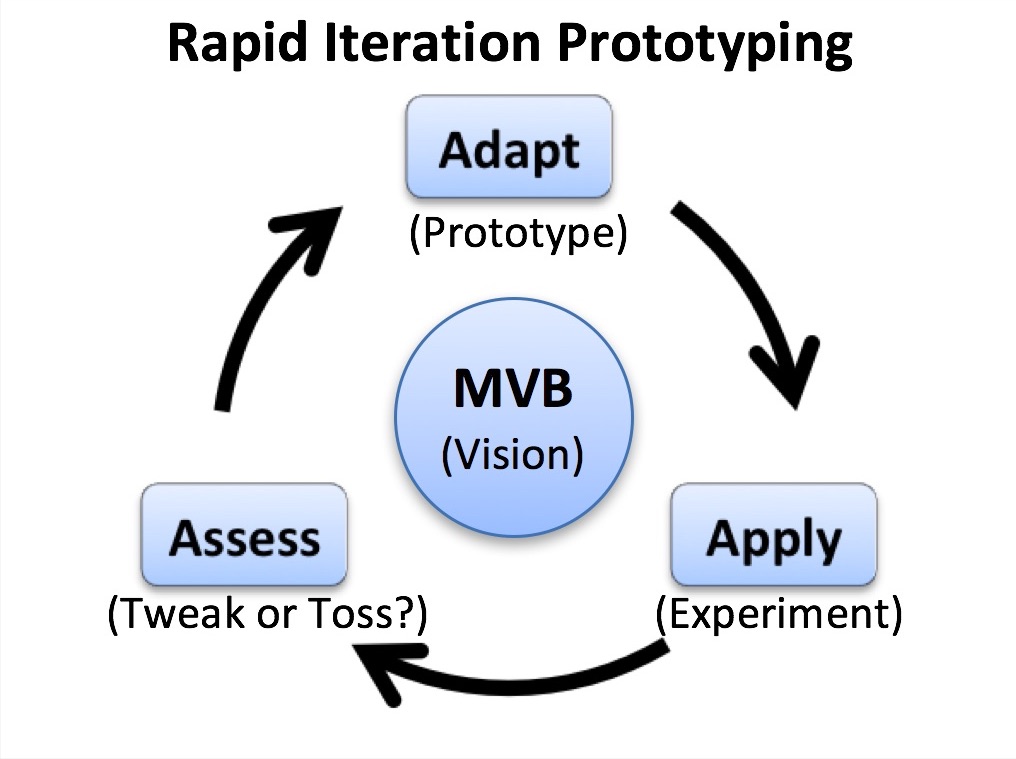

The experimentation part I call Rapid Iteration Prototyping (RIP). RIP is essentially the scientific method applied to the ministries and programs of faith-based communities. RIP is a method of creating and testing new ways to carry on the intentions that lay at the heart of our traditions. We start by creating a hypothesis about what is needed in a new ministry or program. Then we develop a Minimum Viable Program: a no-bells-and-whistles prototype we think will solve the need identified in our hypothesis. Next, we Apply the solution (i.e., test the prototype) for a predetermined length of time, then Assess its effectiveness in resolving the need. If our assumptions were out to lunch, we toss our prototype. But if it’s heading in the right direction, we Adapt it (tweak it by refining the must-haves or adding want-to-haves), then put the adapted prototype through another testing cycle. We do all of this in the service of our MVB overarching vision. I call the process RIP as a reminder that it’s good to let bad ideas die.

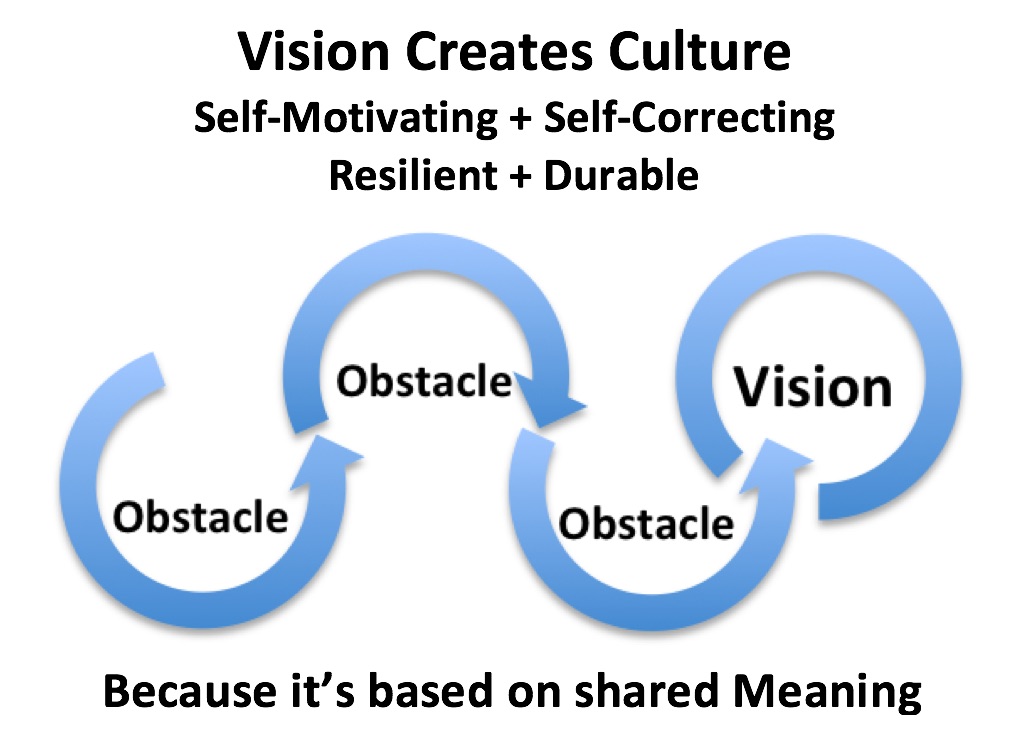

What makes the ideas of Minimum Viable Belief and Vision-Guided Experimentation so important? Because Vision creates Culture: an organizational culture that is self-motivating, self-correcting, resilient, and durable because it based on shared meaning.

As a faith leader and an executive director of a faith-based consulting practice, my primary focus has been on the role of meaning in faith-based communities and organizations, but I believe the practices I have described above are more broadly applicable to any organizations operating in environments of high uncertainty and rapid change. If you would like to talk about how to apply Minimum Viable Belief and Vision-Guided Experimentation in your organization, or to explore any of our services at The FaithX Project, please contact me at ken@faithx.net so set up a free 30-minute consultation.

Ken Howard, M.Div., M.Ed. Ken Howard is founder, executive director, and principal consultant of The FaithX Project (FaithX.net), which provides coaching, consulting, and training to new and revitalizing faith-based communities and organizations. An ordained clergyperson in the Episcopal Church as well as an entrepreneur, Ken founded two congregations before leaving full-time parish ministry at the end of 2016. An author and church futurist, Ken has published two books, is working on a third, and has written a number of articles, including “Singularity: The Death of Religion and the Resurrection of Faith,” forthcoming in the Journal of Religion and Society.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.