Abstract

This chapter makes the case that a brave new world of artificial intelligence (AI), climate change, and global nuclear warfare calls for a paradigm shift towards existential positive psychology (EPP or PP2.0) with existential universals and indigenous psychology as its cornerstones. The three basic tenets of EPP are (1) true positivity is to see and be the light in the darkness; (2) effective coping with adversity and conflicts depend on dialectical/paradoxical rather than binary/rational logic, and (3) a positive outcome (mature happiness) results from the process of self-transcendence and mental disciplines such as mindfulness, meaning mindset, dialectical mindset, and resilient mindset. In addition, this chapter proposes a meaning-centered positive education (PE2.0) based on EPP. This alternative view of positive education, with spirituality and religion as its cornerstone, proposes a new approach to equip children for survival and flourishing in a brave new world. This existential PE points out that happiness and success are the byproducts of (1) accepting the 3 basic tenets of EPP, (2) practicing the five broad strategies of transforming negatives/weakness into positives/strengths, and (3) following the seven existential principles of self-transcendence for daily living. A case study is provided to illustrate the usefulness of the above conceptual framework.

Keywords: Happiness, Success, Suffering, Existentialism, Positive Psychology, Existential Positive Psychology, Indigenous Positive Psychology, Dialectical Logic, Multiculturalism

It is increasingly difficult to raise mentally healthy and well-adjusted children who are able to fulfill their dreams in the brave new world of artificial intelligence (AI), constant technological innovations, and fake news. In an era of disinformation, it is almost impossible for young people to discern who’s telling the truth, what is truth, or what is reality. No wonder why many feel anxious and confused. The current mental health crisis (Harvard, 2022; Sohn, 2022) and the increasing concerns over substance use and suicide rates in teens (Kaliszewski, 2022) demand that a different type of positive education is needed to equip children and adolescents for these new challenges.

There is a consensus that children need additional skills, in addition to academic skills, in our education systems in order to survive and thrive in the 21st century. Numerous soft skills are needed such as self-discipline, active listening, overcoming racial/cultural/social barriers, the ability to endure discomforts and painful experiences, the ability to relate to strangers with empathy and compassion, and the intrinsic motivation of improving and investing in oneself.

Seligman’s initial view of positive education focuses on skills for happiness and cultivating signature character strengths (Seligman et al., 2005, 2009). Even though positive education continues to evolve and become broader in the scope of skills and practices (Moore, 2020), there remains a lack of research in addressing the big questions of how to cope with inescapable suffering, existential threats, and cultural/racial/ideological divides.

In the last 20 years, many researchers have criticized positive psychology’s narrow focus on positivity, positivism, and its Eurocentric orientation (e.g., Ehrenreich, 2009; Friedman & Robbins, 2012; Held, 2004; Wong, 2011; Wong & Roy, 2018). The harmful effects of toxic positivity (Kaufman, 2021a; Princing, 2021; Scully, 2020; Villines, 2021) have attracted increasing public attention. Figure 1 illustrates the possibility of toxic positivity in teachers and students.

Figure 1

Toxic Positivity in Positive Education

The problem of suffering was posed to Seligman shortly after his launching of Positive Psychology (PP) in 1998. His answer in his 2003 Newsletter was: “More commonly we overcome troubles by doing end-runs around them, by deploying our highest strengths as buffers against the setbacks of life.” This is an overly simplistic solution to the complex problem of human suffering. Most children and adults do not know how to cope with all the bad things they must deal with each day.

There is also a growing trend of moving from a Eurocentric PP to indigenous psychology. Numerous psychologists argue that PP is rooted in specific cultural contexts (Chang et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2006; Leong & Wong, 2003; Wong, 2013). Each ethnic/cultural group “inform people about what is worthy, good, and desirable, and about what constitutes the good, virtue, morality, health, and well-being” (Christopher et al., 2014, p. 645). For example. Fadiji et al. (2022) foresee unique contributions from African perspectives towards a more holistic understanding of wellbeing that include spiritual/religious, moral, social, and ecological.

Chang et al. (2022) concluded that “As our findings show, much of the research on positive psychology remains dominated by research produced in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) countries, especially the USA, that are conducted by WEIRD researchers.” Wong & Cowden (2022) share the same concern. More recently, Yeh’s (2023) review paper provide compelling data and argument that indigenous psychological theories need to be included from a global perspective.

The New Paradigm of Existential Positive psychology

Existential positive psychology (EPP or PP2.0) is an attempt to fill this missing link in PP by studying not only the varieties of suffering (Wong & Laird, 2023), but also the different strategies to overcome suffering, as additional arrows in PP’s quiver, such as the dialectic logic or dual-system model (Wong, 2012a), seeing the light in darkness through tragic optimism (Frankl, 1946/1985; Leung et al., 2021), and the multidimensional ways of developing a resilient mindset (Arslan & Wong, 2023).

EPP represents an alternative view of wellbeing, a less travelled narrow path (Peck, 1978): “Life is difficult. This is a great truth, one of the greatest truths. It is a great truth because once we truly see this truth, we transcend it. Once we truly know that life is difficult – once we truly understand and accept it – then life is no longer difficult. Because once it is accepted, the fact that life is difficult no longer matters.” (p. 12)

In a complicated and complex world, existential courage, existential intelligence, meaning transformation, and faith are needed to make the correct choice and do the right thing. Students need to learn the truth that “Life is difficult.” This is a great truth, one of the greatest truths. As Camus observed, “But in the end, one needs more courage to live than to kill himself.”

Atomic habit change can improve your behavior, but you need a quantum-leap to change your life attitude, worldview, or perspective on life, which can set you in a different direction and transform your life. For Stephen Covey (1989), it is the paradigm of put first things first in life – focusing on what really matters. For me, it is the paradigm of seeing beyond all your fears, doubts, and obstacles and connect with the Ultimate Power to fulfill your most cherished dreams.

The main hypothesis of EPP is that flourishing can be achieved only through embracing and integrating human suffering as its foundation. Wong’s research in EPP is characterized by two distinctive themes: (a) existential positive psychology with suffering as the foundation for happiness and wellbeing, and (b) indigenous psychology with the Yin-Yang concept as an Asian view of wellbeing (Wong 2020).

How My Personal History and Culture Shaped My View of Positive Psychology and Positive Education

Personal history is an important factor in precision existential positive psychology, since we believe that what is personal is also universal, and vice versa in practicing meaning therapy. I (P. Wong) have a long history of developing an alternative view of positive psychology and positive education. This is not a matter of personal choice or some accidental event, but the cumulative result of being born as a war baby and being raised in an Asian culture, growing up under Japanese occupation followed by the Chinese civil war, and experiencing systemic discrimination as a refugee and immigrant. I could not help but view life as a constant struggle in a world full of dangers, oppositions, as well as full of opportunities for overcoming and achievement (Kaufman, 2021b; Wong, 2021a).

Even my graduate training in animal learning at the University of Toronto in the late 60s shaped by view on positive education (Wong, 2019a). When Martin Seligman and Steve Maier were doing research on learned helplessness, Abram Amsel and I happened to be conducting a number of important studies on generalized persistence and resourcefulness. We raised and trained baby rats, under deprivation and non-contingent mild aversive stimuli or frustrative non-reward, and then tested them in adulthood in various learning situations. We were pleasantly surprised that the rats “born poor with adversity” actually grew up resilient, demonstrating amazing resourcefulness, persistence, courage, optimism, and capacity for self-control and learning (Amsel, 1992; Wong, 1979). Michael Rosenbaum (1990) has replicated and extended our animal research to demonstrate that the same principle of overcoming frustration is necessary for the development of human resourcefulness.

My stage model of coping with frustration (1995) and my positive psychology of persistence and flexibility (2006) demonstrates the importance of wedding flexibility and agility to the capacity of endurance and persistence. From this framework, I can predict that during prolonged frustration and stress one can react either with invigoration, creative exploration, changing one’s goal, and transcending a hopeless situation or with aggression, addiction, helplessness, and depression. It all depends on whether one has learned a high degree of endurance and flexibility. This theory can explain why there is an increase in random violence mass killing, addition, and mental illness because a lack of high tolerance of frustration and deep inner resources for creative and agile response results in a mental breakdown. My early research on generalized persistence has later led to the development of youth resilience training (Wong & Wong, 2012), the deep and wide hypothesis (Wong & Worth, 2017), and my alternative vision of positive education. More importantly, my animal model lends more support for my central hypothesis of existential universals.

The Objectives of Meaning-Centered Positive Education

In 2012, I was invited by Professor Lee Waters to present my alternative view of positive education to the Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne after my keynote at the first Positive Psychology Conference in Australia. At the meeting, I was not able to get any response to my question: Is there any alternative view to Seligman’s vision of positive education? In my presentation to the School of Education, I focused on (1) the need to understand and adapt to a difficult world full of suffering and opportunities; (2) A supportive environment based on one’s parents, teachers, and the school environment/curriculum which value the students, and (3) Achievement motivation based on meaning, values, and social interest.

I have not changed my views about positive education since 2012. Over the years, I have expanded my view in meaning-centered positive education in in my presentations at many universities – such as Fo Guang University (Wong, 2017a), Tzu Chi University (2017b), University of Hong Kong (2021b), and Adler Graduate Professional School (2022a) – these views were expanded. I want to summarize the main points in this paper.

1. Spirituality and Religion as the foundation of positive education

Students need to learn not only Head Virtues and Heart Virtues, but also Soul Virtues. They need to learn how to fully integrate spirituality and religions with health, knowledge, emotions, and daily living as suggested by the following two quotes:

“Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.” — Aristotle

“The planet does not need more successful people. But it does desperately need more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers, and lovers of every kind.” — Dalai Lama

Spiritual wisdoms of faith, hope, and love (Wong, 2023) incorporate the best from East and West, and draws from the teachings of Jesus, Buddha, Aristotle, Confucius, which are essential for a well-rounded positive education of morality and spirituality. The purpose is to awaken and cultivate one’s innate noble nature, the image of God or Dao.

My wife and I recently attended a funeral service for an old Chinese immigrant. We could not help but feel inspired and uplifted by the life of a good, intelligent man with a very humble and poor beginning. He did not have higher education, fame, or wealth. Yet by dent of hard work and unwavering Christian faith, he was able to become an excellent carpenter, a wise and well-read man, and a respected citizen, a beloved family man. He was able to support a large family and help countless individuals with his generosity and kindness. He left a rich legacy for four generations in his family and countless people. The funeral service was a celebration of a life well lived and a death with hope of glory. The love and respect of his many children and grandchildren were very moving. It is a rare sight in today’s society to see all of his adult children and grand children as well-educated professionals as well as follower of Christ. Many of them took part in the funeral service.

One of his children, a pastor by vocation, used Psalm 23 (NIV, 1978/2011) as a summary of his father’s life.

1The Lord is my shepherd, I lack nothing.

2He makes me lie down in green pastures, he leads me beside quiet waters,

3He refreshes my soul. He guides me along the right paths for his name’s sake.

4Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I will fear no evil, for you are with me;

your rod and your staff, they comfort me.

5 You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies.

You anoint my head with oil; my cup overflows.

6 Surely your goodness and love will follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

These six verses describe a flourishing life based on Christian faith. His father enjoyed the spiritual fruit characterized by content (lacking nothing), inner peace, overflowing joy, and feeling loved and protected all his life. His resilience was characterized by a) his courage and confidence in going through the darkest valley because of his faith in God’s presence and protection, b) his triumph over all his enemies, and c) his hope of God’s goodness and love all his life. It is a hero’s journey of overcoming many trials and tribulations through God’s grace.

This is only one of many cases where one’s religious belief can make a huge impact on human flourishing. When I was a pastor, my first funeral service for the owner of a small Chinese restaurant was attended by hundreds of people who had benefited from his generosity and wise guidance, when they were attending university as students. Many of them gave testimonies how he had changed their lives in a foreign land when they were lonely and confused.

2. The Importance of Belonging and Social Interest

We need to go beyond the individual and consider systemic biases, collective coping, and social actions. According to UNESCO (Giannini, 2021), we are no longer in an emergency but in a “protracted crisis.” We need a recovery package centered on inclusion, resilience, and transformation by:

- Taking every measure to protect the health and wellbeing of students, teachers, and educators.

- Building resilience to prevent future shocks, from health to environmental.

- Providing learners with the knowledge and mindset to cope with the existential threat and create a sustainable, peaceful future.

Alfred Adler is considered the first community psychologist, who considered equality, civil rights, mutual respect, and the advancement of democracy as core values. He taught social interest as a way to improve individual and community wellbeing through social responsibility, social justice, and community engagement. Social interest means that our wellbeing or mental health resides within our community life and connections. Adler’s contribution to positive psychology includes the following:

- He focused on the relational aspects of meaning in life regarding the three major life tasks: work, love, and society.

- He saw courage as a social function. Courage is always needed to cultivate social interests and make useful contributions to others.

- The main motivational force is striving to overcome inferiority though social interest.

- An individual’s social interest is key to his or her success in solving the problems of life and experiencing meaning through relationships. Social interest is the cornerstone of mental health.

- All human beings are driven by the need for significance and belonging in order to overcome inferiority and alienation.

Adler’s contribution to positive education focuses on appealing to the student’s creative power to embark upon a journey of both intellectual growth and cooperative character development. The iceberg analogy from Positive Discipline (n.d.) indicates that the impact on character development first comes from the family, and then in the child’s first school experiences. Children wonder “do I belong?” and “do I matter in some useful ways?” When children feel safe and connected, they feel a sense of belonging and significance. When children do not feel a sense of belonging, they adopt survival behaviors or misbehaviors. Therefore, positive education cannot only depend on individual teachers. The historical development of mankind was possible only because humankind was a community and strove to be a more productive and harmonious community. Those who have already developed a strong social feeling constantly endeavor to ameliorate the hardships of others. In contrast, selfishness is the main source of human suffering.

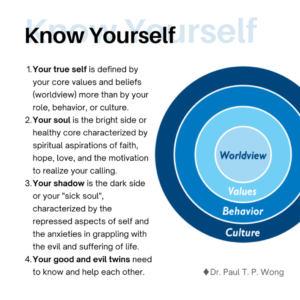

3. Existential Competence of Knowing Oneself and the Meaning of Life

To know oneself is a very challenging task because it means to know and embrace one’s shadow and limitations and learn to live with your undesirable parts in order to become whole, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Knowing Yourself

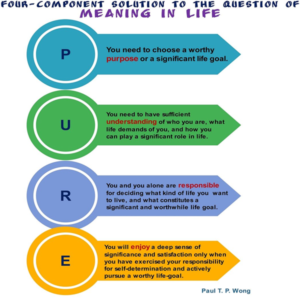

The next important task is to understand the meaning of life. According to Wong (1998a), there are four important constituents for the meaning in life as described in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Four-Component Solution to the Question of Meaning in Life

The PURE model offers principles of personal growth and meaningful living. An inclusive theory of a meaningful life needs to include the following elements:

- Mainly depending on intrinsic motivation so that it is less dependent on extrinsic factors.

- Making full use of human capacities to fulfill potentials.

- Meeting people’s basic needs for love, meaning, work, and play.

- Connecting with the self, others, ecology, the cosmos, and God or a Higher Power.

- Both subjective sense of fulfillment and objective evidence of creative value for others and society.

- Positive evaluations of one’s present life and future legacy.

4. The Meaning of Suffering and How to Transcend and Transform it

Frankl (1946/1985) expanded Nietzsche’s view on suffering. A positive psychology of meaning without including the meaning of suffering is at best incomplete and at worse misleading. All existential philosophers and psychologists begin with the worldview that life is full of suffering, and end with the challenge of figuring out how to live the good life by ameliorating suffering.

According to the Suffering Hypothesis (Wong & Laird, in press), one cannot live a meaningful life without finding meaning in suffering. Meaning and suffering are two sides of the same coin. The “suffering” factor is a missing link in wellbeing research, and this explains why we have difficulty predicting happiness or flourishing in real life (Wong, 2019b). For example, it is difficult to be happy when one cannot regulate negative emotions, and one cannot find meaningful work due to the bad habits of avoiding hard work and failures. Suffering became an even more prominent variable in the era of the pandemic (Wong, Mayer et al., 2021). In short, suffering becomes meaningful when we address ultimate concerns and transcend the dark side of life with courage, faith, wisdom, and meaning-centered positive transformation (Wong, 2022b).

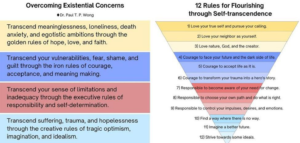

For a detailed description, please see Wong, Arslan et al. (2021). One needs to learn how to overcome existential or ultimate concerns (see Figure 4) by learning how to cope with a variety of suffering through meaning and spiritual values (Wong, 2023; Wong & Laird, 2023).

Figure 4

Overcoming Existential Concerns and the 12 Rules of Flourishing Through Self-Transcendence

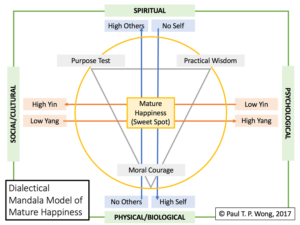

5. Mature Happiness and the Wisdom of Achieving it

A detailed description of mature happiness is found in Wong and Bowers (2018). It is characterized by inner peace, balance, and harmony as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Dialectical Mandala Model of Mature Happiness

As a human being, you are aware of your natural tendency to avoid suffering and seek the pleasure of happiness. Ironically, in spite of all the advances in technology and improvement in living standards, it has become increasing difficult to avoid suffering and find happiness in a complex and rapidly changing society.

The Dalai Lama is also correct in his emphasis on training our mind to think differently; and mindful meditation is one such way. I suggest that we need to develop the following mental disciplines:

- Mindful observation to focus on the present without prejudgement and biases.

- Meaning mindset (Wong, 2012b) to discover something good and beautiful in every situation.

- Resilient mindset (Arslan & Wong, 2023) to embrace life as it is with courage and faith.

- Dialectical mindset (Wong, 2012a) to navigate between positives and negatives to find the happy middle.

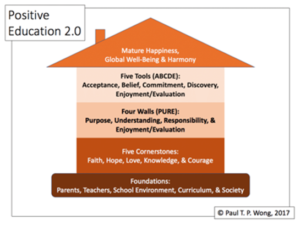

These four mental disciplines enable one to develop mature happiness. In conclusion, all the above points of meaning-centered education can be represented by the following graph (Figure 6). One readily sees that this alternative view is more holistic, existential, and cross-cultural, contributing to global wellbeing.

Figure 6

Meaning-centered Positive Education 2.0

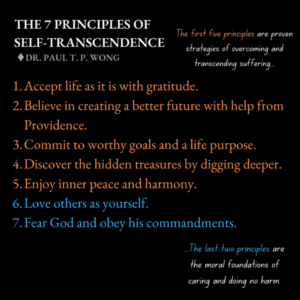

The Seven Principles of Self-Transcendence

Figure 7

The Seven Principles of Self-Transcendence

The seven principles of self-transcendence are summarized in Figure 7. Note that the first five principles have been presented elsewhere as the ABCDE strategy of overcoming traumas (e.g., Wong, 2011). The last two principles are considered part of the moral foundation (Graham et al., 2012) to provide the universal motivation for benevolence or compassion and to prevent people from doing harm to themselves or others. These seven principles of self-transcendence for a deeper life (Wong, 2022b) are based on the new paradigm of existential positive psychology (EPP). They can serve as general guidelines for students and teachers involved in meaning-centered education.

1. Accept Life as it is With Gratitude

Accepting life as it is rather than one’s own illusions or unrealistic expectations is an effective antidote to the human tendency of avoidance. Facing it is, in most cases, a more adaptive strategy. This principle has several meanings. It means accepting death as a part of the life cycle and let death be our lifelong teacher: “A culture that denies death inevitably becomes shallow and superficial, concerned only with the external form of things. When death is denied, life loses its depth.” – Eckhart Tolle

Be grateful for everything in life, including the lessons from suffering. It means that we do not just accept reality grudgingly, but with a sense of gratitude not only for the painful but beneficial experiences, but also for the gift of life (Jans-Beken & Wong, 2019).

True positivity does not deny the bleak reality or an imminent danger. It means to see and be the light in the darkest times: “When it is dark enough, you can see the stars.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

2. Believe in Creating a Better Future with Help from God or Providence

“Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see.” – Hebrews 11:1

Hope is like oxygen. We need to have hope for a better future in order to move forward. More importantly, we need tragic optimism (Leung et al., 2021; Wong, 2009) even in situations which seem hopeless from the human point of view. This kind of hopeless hope requires faith.

Faith requires one to have hope in the future and confidence in what is yet invisible. If one has all the facts and information, there is no need for faith. According to Leo Tolstoy, “Faith is the sense of life, that sense by virtue of which man does not destroy himself, but continues to live on. It is the force whereby we live.”

All the seemingly impossible things in this world are accomplished by people with faith in their visions. Martin Luther King Jr. is one example: “Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.”

3. Commit to Continued Self-Improvement to Achieve Worthy Goals

In addition of Frankl’s (1946/1985) classic Man’s Search for Meaning, there are several popular and helpful books on the subject of finding one’s life purpose, such as Warren’s (2013) The Purpose Driven Life and Tolle’s (2008) A New Earth. Purpose can be understood at three levels – the ultimate meaning of human existence, one’s overall life purpose, or the objective of a specific task (Wong, 2014).

I have already briefly discussed that the direct pursuit of happiness may be a source of our unhappiness. Emmons (2005) also believes that direct pursuit of happiness can be counterproductive, and it is better to pursue worthwhile projects which do not have the attainment of personal happiness as their primary focus.

Frankl (1946/1985) makes love as the central point of meaning, because at the end of your life, you will find your life meaningful not because of how much money you have made but because of how much value you have created for others through your kindness, love, and compassion: “Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.”

4. Discover the Hidden Treasures by Digging Deeper

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.” – Joseph Campbell

“I find that if you dig deep enough you can almost always find something worth the effort.” – Vivian Shaw

The most precious things in life are on the other side of fear. If you dig deep enough and search wide enough, you will always find a way out or get what you are looking for, whether it is a solution for a problem or finding a soul mate. Seek, and you shall find, but you have to keep on seeking and digging. My deep and wide hypothesis (Wong & Worth, 2017) has considerable empirical support. Your life can be an exciting adventure only when you dare to venture out into the ocean and move far, far from the shallow end.

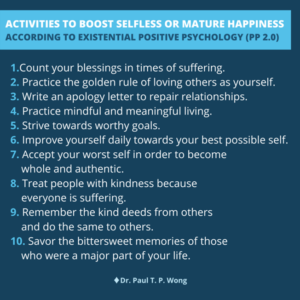

5. Enjoy Inner Peace by Navigating a Dialectical Balance Between Opposites

There are three major types of happiness as shown in Figure 8. The only type of happiness that is sustainable in times of suffering and chaos is the spiritually oriented mature happiness (Wong, 2021c; Wong & Bowers, 2018). See Figure 9 for some activities that can boost one’s mature happiness.

Figure 8

Three Main Types of Happiness

Figure 9

Activities to Boost Selfless of Mature Happiness

6. Love Others as Yourself

This is an overall life attitude of benevolence or caring for others as caring for oneself. This principle recognizes both the personal responsibility of self-care and self-compassion (Neff, 2011) and the social responsibility of caring for others as much as caring for ourselves. What the world needs most is social interest (Adler, 1933/1964) or self-transcendence (Frankl, 1946/1985; Wong, Arslan et al., 2021). Thus, individuals are both a separate unit responsible for how we live and relate to others, and at the same time part of the human family who deserve our love and compassion. This balanced attitude can reduce conflicts between egos and promote world peace.

To extend this idea further, all life is sacred, and we need to love all sentential beings, according to Buddhism. Albert Schweitzer, a Christian medical missionary, made a sense of reverence for all of life as his mission: “If a man loses his reverence for any part of life, he will lose his reverence for all of life.” The golden rule of loving others as oneself is the basis for all major religions.

7. Fear God (or Karma); Therefore, Resist all Temptations and Evils.

The fear of God or a Higher Power is needed to remind us of our boundaries and our need to fear the consequences of harming ourselves or others by going beyond our boundaries. Most human tragedies happen because someone wants to be like God. Power-hungry and ambitious individuals like Hitler, Stalin, or Putin would harm millions of people to secure their power and control, because they have no fear of God’s judgement. “If there is no God, everything is permitted” is widely attributed to Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (Sartre was the first to do so in his Being and Nothingness). Without such transcendental limits – so the story goes – there is nothing ultimately to prevent us from ruthlessly exploiting our neighbours, using them as tools for profit and pleasure, or enslaving, humiliating, and killing them in their millions. All that stands between us and this moral vacuum, in the absence of a transcendental limit, are those self-imposed limitations and arbitrary “pacts among wolves” made in the interest of one’s survival and temporary wellbeing, but which can be violated at any moment (Zizek, 2012).

We need to act as if God exists (i.e., God watches us and holds us accountable). Voltaire repeatedly asserted that “if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.” He meant that belief in God and ultimate justice is necessary to prevent us from doing horrible things to each other as evident in the Holocaust.

We all have experienced such inner struggles. Some could not control their lust for sex. Others find it extremely difficult to resist the greed for more money or power. For each of us, what is most attractive, most difficult to resist, may be our forbidden fruit. There are always consequences when we disobey God’s commandments. Even if one does not believe in God, the law of karma still operates. We always reap what we sow.

An Illustrative Case Study

We want to provide an additional illustrative Case Study written by Lilian Wong, who

has several decades of experience as a high school science teacher, school psychologist, and a licenced psychotherapist. She has worked with hundreds of children and adolescents, practicing meaning therapy and meaning-centered play therapy. Many of the above points are based on P. Wong’s research and clinical experience with adults and L. Wong’s teaching and clinical experience with children. The following is an illustrative case study based on a composite of her clients.

James is a lanky and intelligent 15-year-old boy, suffering from depression, anxiety, and lack of motivation. Like many immigrants from China, he is the only child, and his parents gave up their good paying jobs and migrated to Canada hoping that he can have a better future. Due to language difficulties, his parents had to start from low paying jobs and work very hard in order to improve their social economic status. His parents place a lot of pressure on him to do well in school so that he can get into a good university and get a good paying job.

Unfortunately, based on his online research and his own observation, he no longer believes in his parents’ path for success, because even their own good education and success in China have not translated into a good life in Canada. He has witnessed his parents’ daily struggles, worries, and unhappiness and he does not want to grow up like them.

In addition, he has no friends in Canada since all his friends are in China. Even though he was a top student in China, he only achieves decent grades because of his language and culture handicap, and his lack of interest in school subjects. He is in a very competitive class, and rankism (Fuller, 2013) makes him feel inferior and helpless, resulting in low academic motivation.

He is never recognized or validated for his artistic talents; never encouraged to pursue his own interest. His depression is more like an adolescent’s existential angst and hopelessness, not knowing who he really is, and what future holds. He also feels that struggle for success is pointless, because in the end we all die. He has no religious beliefs, no career plan, and no motivation to work hard on schoolwork. He does not have any of the intrinsic motivation necessary for academic success (Wong, 1998b). He has seen a psychiatrist, but the medication did not help in terms of enhancing his academic motivation or happiness.

The projective test of drawing House-Tree-Person-Family shows a great about his life. His drawing of House clearly shows he is gifted artistically – the picture is rich in details and very good in proportionality and perspective. His Tree is tall and full of branches and foliage, expressing his desire for a flourishing life. But his Person is a hollow person with big square as the head without any features, as if he feels that he in invisible. In his drawing of Family, he is very small, relative to his parents, even though in reality he is taller than them, indicating his inferiority feelings. He is a good candidate for meaning therapy and could benefit from the kind positive education described in this paper. After several sessions of meaning therapy, he shows remarkable progress in (a) understanding the importance of having courage to pursue his dreams, (b) gaining confidence for future success, (c) developing the habit of improving himself daily towards his life goal, and (d) exploring faith in a God or a Higher Power according to his cultural tradition as his resource and support in situations beyond his control.

His relationship with his parents has also improved because he has learnt to open up and they have learnt the importance of listening to his concerns and accepting his dreams of becoming an artist, knowing that it would be a hard life. He also starts making more friends, because he takes the courage to talk to his classmates and learns to connect with his classmates through seeking and offering help (Wong & Wong, in press). In short, this case provides some support for a meaning-centered therapy and education.

Conclusions

The chapter concludes with a vision of personal transformation and existential wellbeing based on the existential wisdom and courage (Wong et al., under review) as well as the enduring spiritual values of faith, hope, and love (Wong, 2023). Here is a tripartite model of global flourishing based on existential positive psychology:

- Faith makes all things possible by seeking divine help for suffering beyond human control.

- Hope motivates us to achieve a meaningful and fulfilling future.

- Love gives us the deep joy of making sacrifices for serving others.

Thus, a flourishing life has three basic constituents: meaning of suffering, meaning of life, and meaning of love. It is not possible to live a meaningful life without overcoming the inescapable limitations, human foibles, and suffering. Faith is the antidote to anxiety and fear. Hope is the antidote to despair, depression, and meaninglessness. Love is the antidote to loneliness and isolation.

We don’t need to live in an ideal world in order to have meaning in our work. According to Viktor Frankl, meaningful work depends on our attitude rather than the nature of our occupation or profession. We can find meaning in whatever we do, if our work attitude is characterized by the following dimensions:

- Whatever we do, do it with all of our heart and soul, as long as it contributes some values to the lives of others.

- Pursue excellence in whatever we do, so that we can take pride in our work and transfer the same habit of excellence to pursuing our calling.

- We all need to make a living, but we can still pursue our calling without quitting our job to put food on the table.

- We can consider all jobs as steppingstones to realize our dreams.

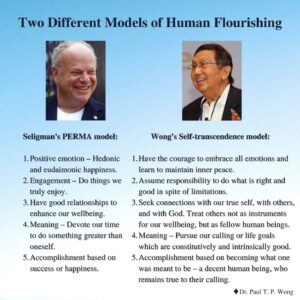

To summarize, Figure 10 compares and contrasts two different views of achieving human flourishing. They can be best considered as Yin and Yang half of the Tai chi symbol. For the future of our children, we need to consider both approaches in developing a curriculum and in teacher education.

Figure 10

Two Different Models of Human Flourishing

References

- Adler, A. (1964). Social interest: A challenge to mankind (J. Linton & R. Vaughn, Trans.). Capricorn Book. (Original work published 1933)

- Amsel, A. (1992). Frustration theory: Many years later. Psychological Bulletin, 112(3), 396–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.396

- Arslan, G., & Wong, P. T. P. (2023). Embracing life’s challenges: Developing a tool for assessing resilient mindset in second wave positive psychology. Journal of Happiness and Health, 4(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.47602/johah.v4i1.53

- Bland, A. M. (2020). Existential Givens in the COVID-19 Crisis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 60(5), 710–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820940186

- Chang, E. C., Downey, C. A., Hirsch, J. K., & Lin, N. J. (Eds.). (2016). Positive psychology in racial and ethnic groups: Theory, research, and practice. American Psychological Association.

- Christopher, J. C., Wendt, D. C., Marecek, J., & Goodman, D. M. (2014). Critical cultural awareness: Contributions to a globalizing psychology. American Psychologist, 69(7), 645-655.

- Covey, S. R. (1989). The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Free Press.

- Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America. Henry Holt and Company.

- Emmons, R. A. (2003). The psychology of ultimate concerns: Motivation and spirituality in personality. Gilford Press.

- Fadiji, A. W., Khumalo, I. P., & Zulu, N. T. (2022). Well-Being in Africa: Towards an Africa(n) Centred Positive Psychology. In L. Schutte, T. Guse, & M. P. Wissing (Eds.), Embracing Well-Being in Diverse African Contexts: Research Perspectives. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology, vol 16. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85924-4_2

- Fowers, B. J., Richardson, F. C., & Slife, B. D. (2017). Frailty, suffering, and vice: Flourishing in the face of human limitations. American Psychological Association.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press. (First published in 1946)

- Friedman, H. L., & Robbins, B. D. (2012). The Negative Shadow Cast by Positive Psychology: Contrasting Views and Implications of Humanistic and Positive Psychology on Resiliency. The Humanistic Psychologist, 40, 87-102.

- Fuller, R. W. (2013, August 11). Curing the poison of “rankism.” Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/somebodies-and-nobodies/201308/curing-the-poison-rankism

- Giannini, S., (2021, January 29). Time to roll out education’s recovery package. UNESCO. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/time-roll-out-educations-recovery-package

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S. P., & Ditto, P. H. (2012). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 58-130). Elsevier

- Harvard. (2022, July 29). Pandemic accelerated youth mental health crisis. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/covid-youth-mental-health-crisis

- Held, B. S. (2004). The Negative Side of Positive Psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44(1), 9-46.

- Jans-Beken, L. G. P. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Development and preliminary validation of the Existential Gratitude Scale (EGS). Counselling Psychology Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1656054

- Kaliszewski, M. (2022, September 15). The link between substance abuse and suicide in teens. American Addiction Centers. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/blog/link-between-substance-abuse-suicide-in-teens /

- Kaufman, S. B. (2021a). The opposite of toxic positivity: Tragic optimism. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/08/tragic-optimism-opposite-toxic-positivity/619786 /

- Kaufman, S. B. (2021b, August 2). Paul Wong: Existential Positive Psychology. The Psychology Podcast. https://scottbarrykaufman.com/podcast/paul-wong-existential-positive-psychology/

- Kim, U., Yang, K.-S., Hwang, K.-K. (Eds.) (2006). Indigenous and cultural psychology: Understanding people in context. Springer.

- Leong, F. T. L., & Wong, P. T. P. (2003). Optimal functioning from cross-cultural perspectives. In B. Walsh (Ed.), Counseling psychology and optimal human functioning (pp. 123-150). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Leung, M. M., Arslan, G., & Wong, P. T. P. (2021). Tragic optimism as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering and the psychometric properties of a brief version of the life attitudes scale (LAS-B). Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 646843. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646843

- Mayer, C.-H. (2021). Albert Camus – A psychobiographical approach in times of Covid-19. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644579

- Moore, C. (2020, February 24). What is positive education, and how can we apply it? Positive Psychology. https://positivepsychology.com/what-is-positive-education/

- Neff, K. (2011). Self-Compassion: Stop Beating Yourself Up and Leave Insecurity Behind. HarperCollins Publishers.

- New International Version (NIV) Bible. (2011). New International Version (NIV) Bible (Original work published 1978). Biblica.

- Peck, S. M. (1978). The road less travelled: New York: Simon & Schuste

- Positive Discipline. (n.d.). Iceberg Jungle Activity with Posters (Download). https://www.positivediscipline.com/products/iceberg-jungle-activity-posters-download

- Princing, M. (2021, September 8). What you need to know about toxic positivity. Right as Rain. https://rightasrain.uwmedicine.org/mind/well-being/toxic-positivity

- Rosenbaum, M. (1990). The role of learned resourcefulness in the self-control of health behavior. In M. Rosenbaum (Ed.), Springer series on behavior therapy and behavioral medicine, Vol. 24. Learned resourcefulness: On coping skills, self-control, and adaptive behavior (p. 3–30). Springer Publishing Co.

- Scully, S. M. (2020, July 22). ‘Toxic positive’ is real – and it’s a big problem during the pandemic. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/toxic-positivity-during-the-pandemic

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Authentic Happiness. University of Pennsylvania. https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/newsletters/authentichappiness/suffering

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293-311.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421.

- Sohn, E. (2022, August 24). Tackling the mental-health crisis in young people. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-02206-9

- Tolle, E. (2008). A new earth: Awakening to your life’s purpose. Penguin Life.

- Villines, Z. (2021, March 30). What to know about toxic positivity. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/toxic-positivity/

- Warren, R. (2013). The purpose driven life: What on earth am I here for? Zondervan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1979). Frustration, exploration, and learning. Canadian Psychological Review, 20, 133-144.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1995). A stage model of coping with frustrative stress. In R. Wong (Ed.), Biological perspectives on motivated activities (pp. 339–378). Ablex Publishing.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998a). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998b). Academic values and achievement motivation. In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 261-292). Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2006). The positive psychology of persistence and flexibility. Positive Living Newsletter. http://meaning.ca/archives/presidents_columns/pres_col_feb_2006_persistance-and-flexibility.htm

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 52(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012a). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). What is the meaning mindset? International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 4(1), 1-3.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2013). Positive psychology. In K. Keith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of cross-cultural psychology. Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2014). From attunement to a meaning-centred good life: Book review of Daniel Haybron’s Happiness: A very short introduction. International Journal of Wellbeing, 4(2), 100-105. doi:10.5502/ijw.v4i2.5

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017a, October 11). Meaning-centered positive education. Invited talk presented at Fo Guang University, Yilan, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017b, October 3). Lessons of life intelligence through life education. Invited talk presented at Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019a, May 7). Learned helplessness or learned resourcefulness? Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. http://www.drpaulwong.com/learned-helplessness-or-learned-resourcefulness/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019b). Why and How I Developed the Positive Psychology of Suffering. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. http://www.drpaulwong.com/why-and-how-i-developed-the-positive-psychology-of-suffering/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020). Made for resilience and happiness: Effective coping with COVID-19 according to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021a, October 18). The surprising science of suffering: Why is suffering necessary for flourishing? [Invited talk] The Harvard Human Flourishing Program. http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-surprising-science-of-suffering-why-is-suffering-necessary-for-flourishing/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021b, April 10). Self-transcendence: The key to meaning and wellbeing during Covid-19 [Keynote]. Centre for Advancement in Inclusive and Special Education Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong International Webinar Series on Students’ Well-being [Virtual webinar]. http://www.drpaulwong.com/self-transcendence-the-key-to-meaning-and-wellbeing/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021c, August). Beyond Happiness and Success: The New Science of Self-transcendence. Keynote address presented at the 11th Biennial International Meaning Conference, Toronto, Canada.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022a, May 7). Adler’s contribution to positive psychology and positive education [Invited talk]. Adler Graduate Professional School Summer Colloquium 2022. http://www.drpaulwong.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Adler-University-Colloquium-v5.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022b, April 26). The best possible life in a troubled world: An existential positive psychology perspective [Symposium]. Positive Psychology in Cultural and Contextual Perspectives. http://www.drpaulwong.com/the-best-possible-life-in-a-troubled-world-an-existential-positive-psychology-perspective

- Wong, P. T. P. (2023). Spiritual-existential wellbeing (SEW): The faith-hope-love model of mental health and total wellbeing. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 11(2). http://www.drpaulwong.com/spiritual-existential-wellbeing

- Wong, P. T. P., Arslan, G., Bowers, V. L., Peacock, E. J., Kjell, O. N. E., Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T. (2021). Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the Self-Transcendence measure-B. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648549

- Wong, P. T. P., & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society (pp. 112-134). IGI Global.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Cowden, R. G. (2022). Accelerating the science and practice of psychology beyond WEIRD biases: Enriching the landscape through Asian psychology. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1054519

- Wong, P. T. P., Cowden, R., G., Yu, T. T. F., & Arslan, G. (Under review). Existential wellbeing: Towards a new paradigm of conceptualizing wellbeing and measuring existential wellbeing.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Laird, D. (2023). Varieties of suffering in clinical setting: Re-envisioning mental health beyond the medical model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1155845

- Wong, P. T. P., & Laird, D. (in pesss). The suffering hypothesis: Viktor Frankl’s spiritual remedies and recent developments. In C. McLafferty, Jr. and J. Levinson (Eds.), Logotherapy and Existential Analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute of Logotherapy Frankl Institute Vienna (Vol. 2). Springer Research.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Roy, S. (2018). Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), Routledge international handbooks. The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology (pp. 142–160). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (2012). A meaning-centered approach to building youth resilience. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 585–617). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (in press). Connect-2: The Exercise of Offering and Receiving Help for Children. In L. L. Armstrong (Ed.), Experiential and Play Therapy Interventions for Virtual Therapy for Children, Youth, and Families.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Worth, P. (2017). The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity [Special issue]. Psychology and Education, 54(3/4). http://www.psychologyandeducation.net/pae/category/volume-54-no-3-4-2017/

- Wong, P. T. P., & Yu, T. T. F. (2021). Existential suffering in palliative care: An existential positive psychology perspective. Medicina, 57(9), 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57090924

- Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., & Arslan, G. (Eds.). (2021). Existential Positive Psychology (PP2.0) and the new science of flourishing through suffering [Editorial]. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800308/full

- Yeh, K.-H. (2023). Constructing Indigenous Psychological Theories From A Global Perspective: Taking Filial Piety Model As An Example. Review of General Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680231152191

- Zizek, S. (2012, April 17). If there is a God, then anything is permitted. ABC Religion & Ethics. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/if-there-is-a-god-then-anything-is-permitted/10100616

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (in press). Meaning-Centered Positive Education (PE2.0) based on the new paradigm of Existential Positive Psychology (EPP). In G. Arslan & M. Yıldırım (Eds.), Handbook of Positive School Psychology Interventions: Evidence-Based Practice for Promoting Youth Mental Health.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.