Dr. Paul T. P. Wong’s autobiography, A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith, is published in weekly installments. Stay updated here.

My childhood was in China, but I became an adult in Hong Kong. Perhaps the ordeal of escaping from China as a refugee turned me into an adult, almost overnight. Perhaps it was because I had the added responsibility of taking care of my two younger brothers, Oscar and Joshua.

My family was very fortunate that father arrived in Hong Kong ahead of us and booked the Kowloon Hotel on Nathan Road as our temporary home. Nathan Road was—and still is—the heart of Kowloon, the busiest main street, lined with retail stores and restaurants. At night, Nathan Road was lit up with all kinds of neon signs; it was an eye opener for me.

Present day Nathan Road.

Initially, we did not have to go to school because it was already the beginning of the second semester. Thus, we had a lot of free time. Other than a couple of hours a day learning English from a tutor, we just spent all our time at the hotel or roaming the streets.

We had very limited interactions with the local residents. During the early days in Hong Kong, I only picked up a few Cantonese words, such as gwai lou (鬼佬), which means “foreign ghost” and lou hing (老兄), the literal translation of which is “old friend,” but in those days it was used in a mocking way to address the Mandarin-speaking Chinese refugees.

Shopping Mecca

It was a cultural shock for me to move from a quiet and sparsely populated city to a cosmopolitan crowded with people and cars. In the 50s, Hong Kong was already recognized as the “pearl of the orient”—a shopping paradise for the rich, who could purchase all kinds of luxurious brands from all over the world and expensive jewelry pieces, ivory carvings, and Chinese paintings. Hong Kong was a dazzling sight for a boy from Northern China.

At first, my explorations were limited to Tsim Sha Tsui, a popular shopping district for tourists. I often went out with baby Oscar in a stroller and Joshua walking beside me. Now looking back, I am really amazed at how well-behaved these two boys were; maybe they had been disciplined by the long voyage in a very restricted cabin space on the ship.

Present day Tsim Sha Tsui.

During one of my outings, I had a memorable encounter with a woman and her two young children. When she learned that we lived in the hotel, she felt sorry for us because we had to consume hotel food every day. Thus, she asked me to take a pot of home-cooked food to my mother. I still remember the delicious taste of the Chinese-style stewed pork (紅燒豬肉) cooked with a few pieces of cuttlefish and hardboiled eggs. I liked it so much that I learned to recreate this dish many years later. Her family were also refugees from China. I have never met her again, but this incident has stayed with me all these years to remind me of the natural connection and kindness between strangers among refugees.

When I did window shopping, I was not interested in toys or clothing. Instead, I was only attracted to leather briefcases and watches. I had no idea why these items caught my fancy. I visited several stores to decide which one I would buy if I had the money. At that time, I did not have the faintest idea about my future career, but in a child’s mind, it must be very “cool” to go to school with a wrist watch and an attaché. However, in real life, I did not receive my first watch as a gift from my father until I was a university student, and I did not have a leather briefcase until I became a professor.

The Dark Side of Hong Kong

Present day Temple Street.

Father bought two flats in a newly constructed condo on Temple Street without any knowledge that this street was then famous for gang activities and prostitution. The crime image of Temple Street has been reinforced by several Hong Kong movies on the Triads. Now, Temple Street is well-known for its night market to both locals and tourists.

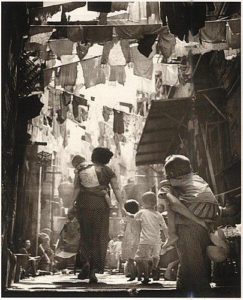

When we moved to Temple Street, I began to explore side streets and alleyways and discovered the dark underbelly of Hong Kong—it was a hellhole for the poor. Many of them had to sell their bodies or souls in order to stave off hunger for another day. With so many refugees struggling for survival, people were willing to do anything to make a living; they called it wan sik (搵食) or “finding food.”

A typical scene of a side street in the 50s.

Despite the poverty and hardships, there was a great deal of energy and creativity at the street level. The city was bursting with vitality and zest for life. Almost everyone was busily engaged in something to eke out a living. Unskilled young men pulled rickshaws or worked as general coolies. Even women did hard labour, such as breaking rocks into smaller pieces with sledgehammers for construction purposes. The fortunate ones found regular assembly line jobs at one of the textile or garment factories.

Peddling in the streets was the most common business. All kinds of hawkers sold food items and other goods in the streets without a licence. They would scurry all over the place with their wares the moment someone shouted out zau gwai (走鬼), which means “Run! The cops are coming!” It was a cat and mouse game. These vendors had to pay protection fees to the local Triad members, but that did not prevent them from frequent harassment and arrest from the police.

In spite of rampant Triad activities and corruption in the 50s and 60s, ordinary hardworking people still had the freedom and opportunities to pursue their dreams, and many succeeded in rising from rags to riches. For example, the father of a young person from my church used to sell homemade candies in the street to support his family; later, he became a successful businessman. Another friend started his garment business in his own small apartment, but later owned a garment factory. There are countless stories of successful entrepreneurs who became rich through their ingenuity and hard work. The Hong Kong miracle in the 50s and 60s was due to a number of factors—capital from Shanghai, an entrepreneurial spirit, hard work, and the true grit needed to create a new life.

For those without money, Hong Kong was a heartless city. If you didn’t have money, you wouldn’t be able to get on a Star Ferry to cross the harbour from Kowloon to Hong Kong Island. I learned firsthand the harsh reality of poverty after my father went bankrupt; this is another story for later.

A Sanctuary for Chinese Refugees

During the 50s, as many as 10,000 refugees escaped to Hong Kong every month. Close to two million refugees flooded to Hong Kong between the 50s and 70s to escape from political persecutions, the Great Leap Forward (1955-1961), and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

The Cultural Revolution represented a tectonic shift in traditional values in China. When Mao Zedong incited the youth (Red Guards) to rise up against the “revisionist” elements in the party, people were dragged out of their homes, paraded through streets in dunce caps, and attacked verbally and physically in endless “class struggle sessions.” Anyone that was remotely related to the capitalist class or reformers was subject to arrest and attack by the young mobs.

People were no longer treated as human beings; they were judged harshly according to whether they belonged to the right “class” or correctly adhered to Mao’s radical ideology. During those dark days, children turned against parents, students turned against their teachers, and friends betrayed friends in blind obedience to Mao’s radical ideology. As a result, the moral foundation of Chinese civilization was shattered to its roots. China has never fully regained her traditional values ever since.

Many of the asylum seekers lived in squalor, yet they would rather take their chances living in the street as free people than living in constant fear of becoming victims of the endless brutal political persecutions. To them, Hong Kong was a beacon of hope and a sanctuary of freedom. No matter how hard the struggle for existence, life had meaning as long as they could have their family together and were free to create a better future for their children. This was the historical and cultural backdrop that eventually led to the Umbrella Movement half a century later.

The Umbrella Movement

People were equipped with umbrellas to protect them from inclement weather as well as teargas from the police.

I can fully understand the Umbrella Movement (Sept. 26-Dec. 15, 2014) when tens of thousands of young people stopped attending their schools and gave up their comfortable beds in order to stay on the streets day and night to protest the lack of democracy in electing the next Chief Executive Officer. The protestors were already alarmed by the Chinese government’s heavy-handed intrusion into every aspect of Hong Kong life, from education and the media to the elections. They knew that, eventually, in 2047, Hong Kong would become just one of China’s cities, but they were fearful of China’s blatant attempts to “mainlandize” Hong Kong during the transition period when Hong Kong was governed by the special arrangement of “one country two-systems.”

Many of the protestors were children or grandchildren of refugees who had sought asylum in Hong Kong. They had grown up listening to stories about the horrors of the Chinese Communist regime. It is perfectly understandable that they should be fearful of living under communist rule sooner than 2047. No amount of political propaganda, no matter how sophisticated and deceptive, could compete with what people have actually experienced and witnessed. The Umbrella Movement was a spontaneous political awakening among the young people in Hong Kong. They seized the opportunity to speak up and defend their democratic rights and way of life guaranteed by Hong Kong’s basic law before it was too late.

I stood in total solidarity with these idealistic young people, who risked imprisonment and their own future to stand up against the iron hand of the Chinese government. At that time, I thought to myself that if I were still in Hong Kong, I would have actively supported their movement in any way I could. Their courage and idealism meant that there is still hope for Hong Kong and Taiwan.

I was glued to TV during the entire duration of the Umbrella Movement and wrote poems to express my support. Here is one poem which identified these youngsters as the True Patriots:

We are the true patriots!

Stand on guard day and night,

For our beloved homeland—

The last bastion for democracy,

The only hope for freedom lovers.

Let’s defend every barricade,

With sweat, tears, and blood,

Until victory is finally won.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.