Abstract

Background

In Germany, only limited data is available on death attitudes and existing measurements are not easily applicable. This study reports the translation and adaption of the Death Attitudes Profile- Revised (DAP-R) into German (DAP-R-GR) using cross-cultural adaption process methodology.

Methods

The DAP-R was translated following proposed guidelines for cultural adaption. Face validity was investigated by means of Kendall’s W concordance coefficient test of interrater reliability. As for the main sample, prior to data collection, a power analysis concerning sample size for split-half reliability (bivariate correlation, two tailed) was performed by means of G-power, resulting in a suggested sample size of N = 138. As for the confirmatory factor analysis, we set a sample size above 200 participants. A total of 216 medical students of the Heinrich Heine University Duesseldorf participated in this study. The internal consistency of the DAP-R-GR Scales was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Split-half-reliability was estimated using the Spearmann-Brown coefficient. Correlations between the subscales were measured with Spearman’s correlation coefficient as the data was not normally distributed. In order to conduct the confirmatory factor analysis, the covariance matrix was introduced to AMOS 22.

Results

As for the face validity, all items showed fair to good W-values ranging from .30 to .79. Data of the main sample showed that means and standard deviations are in line with the original study. Internal consistency of the five subscales were in line with the original measure and ranged from a low of .61 (Neutral Acceptance) to a high of .94 (Approach Acceptance). Split-half reliability analysis also yielded to good results as the Spearman-Brown-coefficient was .83. Confirmatory factor analysis slightly diverges from the original scale, as in that study all items loaded .40 or greater on at least one component.

Conclusion

Our data suggest an overall good reliability of the German version of the DAP-R (DAP-R-GR). DAP-R-GR promises to be a robust instrument to establish normative data on death attitudes for the use in German speaking countries.

Trial registration

Ethics committee of the Heinrich Heine University Trial Registry No. 4921R (date of approval 13.01.2015).

Keywords

Death Attitudes, Death Anxiety, Death Acceptance, Denial of Death, Multidimensional Measure, Death Attitude Profile-Revised, Cultural Adaption, DAP-R-GR, factor analysis, validation, test construction

Background

To examine people´s attitude towards death and dying in Germany requires that research should not only concentrate on optimizing the medical care but also deal with social, cultural, religious and ethnic circumstances (1). Many people do not think about death all that much. However, when prompted to consider the idea of death, most people describe a feeling of apprehension or uncomfortable feeling. Reactions range between anxiety, denial and acceptance of death (2, 3). Hence, this study focuses on the different attitudes people express towards death. The public discourse project “30 thoughts on death” (http://www.30gedankenzumtod.de [German website]) is a joint research project between universities in Germany and follows the call for research and public dialogue on this topic (4).

Nowadays, it is often during diagnosis of a life-limiting disease that people consciously ponder thoughts of personal dying and death for the first time (5). Once confronted with death, primary anxious affect seems to be a natural response to death awareness. Nyatanga and de Vocht (6) p. 412, define death anxiety as “an unpleasant emotion of multidimensional concerns that is of an existential origin provoked on contemplation of death of self or others”. (5) describes the essential function of anxiety as reparative. While a low level of anxiety can be motivating, a high level can have detrimental effects. Prolonged overt anxiety can lead to a state of terror or existential dread. Following Terror-Management-Theory (TMT) research, failure of protective psychogenic mechanisms and defense strategies, aiming to bolster self-esteem and ultimately reduce anxiety experience, leads to overt annihilation anxiety (7, 8). In accordance with TMT, individuals who have high self-esteem and who have strong worldview beliefs often do not think about death all that much, nor fear it consciously. Those individuals often express an attitude of death acceptance. However, Wong and Tomer (1999) argued that a meaning-oriented approach towards death acceptance may reduce the terror of death. (9, 10) has in this context presented his meaning-management theory (MMT) of death acceptance. MMT is rooted in existential-humanistic theory (11) and constructivist perspectives (12), but it also incorporates cognitive-behavioral processes. It is a comprehensive psychological theory about how to manage various meaning-related processes to meet basic needs for survival and happiness.

Wong et al. (13) developed the Death Attitude Profile-Revised and identified three types of death acceptance – Natural Acceptance (accepting death as a natural process of life), Approach Acceptance (looking forward to a blessed afterlife) and Escape Acceptance (accepting death as a better alternative to present sufferings. Research has shown that Natural or Approach death acceptance correlates with personal meaning, e.g. individuals who see their lives as fulfilling have constantly be shown to express less death anxiety. (13-21). One relevant application of the DAP-R measure lies in its ability to measure these different attitudes as to understand more subtlety how individuals react in situations of death confrontation and mortality salience, for example when being confronted with a life-limiting illness diagnosis or when working around death and dying is part of the professional role description, such as in Hospice and Palliative Care (22).

In Germany, only limited data is available on death attitudes and existing measurements are not easily applicable. The existing measurements are complex and time consuming and data on psychometric properties are limited (23-25). DAP-R has been translated and tested in several countries, but no German version exists to date. Hence, within this study, we report the translation and adaption of the previously validated measure DAP-R into German using cross-cultural adaption process methodology (26).

Methods:

Sample

A total of 216 medical students of the Heinrich Heine University Duesseldorf, at least 18 years of age or older and sufficiently fluid in German Language participated in this study.

Death Attitude Profile- Revised

The Death Attitude Profile- Revised (DAP-R; (13) captures attitudes towards dying and death. The measure consists of 32 items, which are assigned to 5 dimensions. The measure has to be answered on a 7-point Likert Scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) with random polarity patterns (beginning with strongly disagree or strongly agree, or vice versa). Total scores on each subscale are the average of the items of the subscale. The five dimensions are as following:

- Fear of Death (Todesfurcht). This dimension captures the fear of dying and death. Issues related to dying and death are complex and result from different reasons. (e.g., “The prospects of my own death arouses anxiety in me.”). The internal consistency of the original dimension is α = 0.86 (seven items: 1, 2, 7, 18, 20, 21 and 32).

- Death Avoidance (Vermeidungshaltung). This dimension measures the avoidance of thoughts and feelings towards dying and death. It is important not to see Death Avoidance as absence of Fear of Death. (e.g., “I always try not to think about death.”). The internal consistency of the original dimension is α = 0.88 (five items: 3, 10, 12, 19 and 26)

- Neutral Acceptance (Neutrale Akzeptanz). This dimension captures a neutral attitude towards dying and death. Death here is considered as an integral part of life. (e.g., “Death should be viewed as a natural, undeniable, and unavoidable event.”). The internal consistency of the original dimension is α = 0.65 (five items: 6, 14, 17, 24 and 30)

- Approach Acceptance (Akzeptanz von Tod als Schwelle zum Jenseits). This dimension implies a belief in a happy afterlife. (e.g., “I believe that I will be in heaven after I die.” The internal consistency of the original dimension is α = 0.97 (ten items: 4, 8, 13, 15, 16, 22, 25, 27, 28 and 31).

- Escape Acceptance (Akzeptanz von Tod als Ausweg). This dimension captures positive attitudes towards death in the light of suffering. When life is full of pain and distress, death may occur as welcomed alternative (e.g., “Death will bring an end to all my troubles.”). The internal consistency of the original dimension is α = 0.84 (five items: 5, 9, 11, 23 and 29).

Translation of DAP-R

The DAP-R was translated following the proposed guidelines for cultural adaption by Guillemin et al. (26). An overview of the translation process is shown in Figure 1 (Flowchart Translation process). In order to study the health care needs of people with diverse cultural backgrounds, research instruments must be reliable and valid in each culture studied. (27, 28). If quantitative measures are used in research, it is necessary to translate these measures into the language of culture being studied. Without verification of translation adequacy, differences found while using the target language version in the target population, might be due to errors in translation, rather than being true differences between countries (29). The original measure “Death Attitude Profile-Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes towards death” (13) was translated from English to German by three independent professional translators (target language versions (German): G1, G2, G3). According to (26), differing interpretations and translation errors of ambiguous items in the original can be detected by this procedure. If the translator is aware of the objectives underlying the measure a more reliable restitution of the intended measurement can result, while translators who are unaware of these objectives may draw unexpected meanings from the original tool (30). We used only qualified translators who translated into German as their mother tongue (31).

In a second step the resulting German target versions G1-G3 of the measure were back-translated into English to foreclose mistakes occurred by the translation and to verify the semantic equivalence between the source language (SL) version and the target language (TL) version (back-translation versions B1, B2, B3). As next step, we conducted a multidisciplinary Consensus Panel. The aim of this panel was to produce a preliminary final version of the German DAP-R (FB), which would be equal in semantic, idiomatic, empirical and conceptual way, based on the diverse forward- and backward translations received as described before. Every participant of the panel received the original version of DAP-R, the forward-translations G1-G3, the back-translations B1-B3, a proposed version by the head of the panel/research project, and guidelines how to conduct the panel. The panel met on 28th of March and 9th of April in 2014 and a preliminary final version was produced on 9th of April.

Figure 1: Flowchart Translation process

Procedure

To determine empirically the face validity of the proposed five dimensions of the DAP-R, we asked an independent group of 32 medical students, to place each item into, what they believe is the most conceptually appropriate category.

The main study took place at the Heinrich Heine University. Attendees provided informed consent for participation, by finally transferring their results to our database, via a button at the end of the survey.

Data analysis

Face validity was investigated by means of Kendall’s W concordance coefficient test of interrater reliability (32).

As for the main sample, prior to data collection, a power analysis concerning sample size for split-half reliability (bivariate correlation, two tailed) was performed by means of G-power (33), resulting in a suggested sample size of N = 138. As for the confirmatory factor analysis, we set a sample size above 200 participants (34).

First, missing data on the DAP-R were evaluated. Missing data was less than 1% in case of each variable and were classified as being ‘missing completely at random’ as Little’s Missing Completely at Random Test was not significant (χ2 (705) = 685.66, p = .692). Missing data were replaced with the Expectation-Maximization algorithm for each subscale.

After conducting descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations and ranges), normal distribution of each subscale was evaluated with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The internal consistency of the DAP-R Scales was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Split-half-reliability was estimated using the Spearmann-Brown coefficient. Correlations between the subscales were measured with Spearman’s correlation coefficient as the data was not normally distributed. Then, subsamples were assessed for systematic differences concerning age, gender, semester, educational background and prior experience with death.

In order to conduct the confirmatory factor analysis, the covariance matrix was introduced to AMOS 22 (35). After introducing the data, maximum likelihood estimation was used and various goodness-of-fit estimations were analyzed to assess the fit of the data: chi-square (χ2), χ2/degree of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Mean Square Residual (SRMR). As the χ2 statistic is sensitive to sample size issues overestimating the lack of fit thus it was not relied upon as a basis for acceptance or rejection of the model (e.g., (36, 37). Thus the CMIN/DF is preferred instead, values between 1 and 3 indicate a good fitting model (38). According to Hu and Bentler (1998), RMSEA values below .06 indicate a good fit, while other authors accept values below .08 as a reasonable fit of the model (39). SRMR values below .8 are considered a good fit (40), while CFI values above .90 indicate an acceptable fit and above .95 an excellent fit of the model (38, 40, 41). As for the factor loadings, (34) suggested the following cut-offs: .32 (poor), .45 (fair), .55 (good), .63 (very good) and .71 (excellent).

Results

Face validity sample

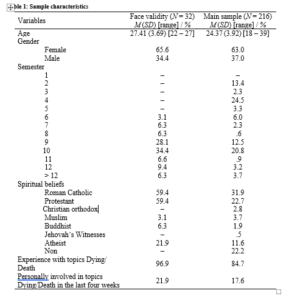

Demographic data of the face validity sample (n = 32) are represented in Table 1, while results of face validity are shown in Table 2. Kendall´s W test revealed fair to good values indicating an acceptable inter-rater agreement and thus an acceptable face validity.

Table 2: Results of Kendall’s W face validity. (uploaded as additional file)

Main sample

Demographic data of the 216 participants are presented in Table 1. Most of the participants were female (63%) and the average age was 24.37 years (SD = 3.92). We had participants from all semesters (see Table 1). A total of 66.2% reported having a fundamental spiritual belief. The majority had previous experience with dying or death, but was not personally involved in these topics in the last four weeks (see Table 1).

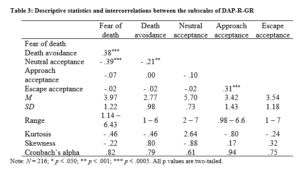

Scale characteristics and reliability

Means and standard deviations of the five factors were similar to the data obtained in the original study of (13) (see Table 3). Although in most cases there were no problematic levels of skewness and kurtosis, the scales did not show a normal distribution (in each case, Shapiro-Wilk tests were p < .05). Internal consistency of the five subscales were in line with the original measure (13) and ranged from a low of .61 (Neutral Acceptance) to a high of .94 (Approach Acceptance) (See Table 3). Split-half reliability analysis also yielded to good results as the Spearman-Brown-coefficient was .83.

Similarly to the original version, our data indicated that the factors are quite independent. Only the Fear of Death factor correlated positively with Death Acceptance and both of them were negatively associated with the Neutral Acceptance (see Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences concerning age, gender, semester, educational background and prior experience with death in any of the DAP-R subscales, p > .05.

Confirmatory factor analysis

The assumption about the five-factor structure of the instrument was assessed with confirmatory factor analysis on the data during the first assessment (T1, n = 216). The fit was on the border of being acceptable, χ2 (454) = 811.74, p < .001, CMIN/DF = 1.79, CFI =.90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .08. Because of the possibly problematic fit, the standardized residual covariance matrix was assessed. Highest covariance was found between Items 1 and 18 (MI = 17.11). This connection makes sense between these two items, as they have very similar meaning. Also, a number of medium-low covariances (MI between 10 and 15) were found in the factor of Approach Acceptance, showing that some of the items may be redundant in this factor. But after allowing the error terms correlate between Items 1 and 18, the model fit became excellent, χ2 (453) = 791,461, p < .001, CMIN/DF = 1.74, CFI =.90, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .08. The only acceptable indicator was the CFI, which is understandable as in the case of DAP-R, some items and subscales do not correlate (see Table 3). Figure 2 depicts the standardized solution of the five-factor model with the addition of the two error covariances. The analysis of the factor loadings shown in Figure 2 suggest that Item 1 with a factor loading of .13 (and possibly Item 3 with a factor loading of low as .30) may be removed from the model, as it does not load on the factor ‘Fear of Death’. Further analysis showed that this item couldn’t be placed on any of the remaining four factors. This data slightly diverges from the original scale, as in that study all items loaded .40 or greater on at least one component (13).

Figure 2: Five-factor confirmatory factor analysis model of DAP-R-GR (To Be uploaded)

Discussion

This study reported the translation process of the German version of the Death Attitude Profile- Revised (DAP-R-GR), a multidimensional questionnaire to measure death attitudes, and its validation in German medical students.

As for the face validity, all items showed fair to good W-values ranging from .30 to .79. Data of the main sample showed that means and standard deviations are in line with the original study. Most of the participants were female, in accordance with statistical findings that show that in the year 2012, 65% of German university graduates in medicine were female (42).

Overall, our data suggest an overall good reliability of the German version of the DAP-R (DAP-R-GR). The subscales showed relatively high internal consistencies ranging from .65 to .88 and our data showed a good split-half reliability of .83, which has not been tested in the original version of the measure. Similarly to the original version (13), the factors were quite independent, only the Fear of Death factor correlated positively with Death Acceptance and both of them were negatively associated with the Neutral Acceptance. Scores on the subscales did not differ based on the age, gender, semester, educational background and prior experience with death. Thus these variables seem to have no influence on attitudes towards dying and death. These data differ from the original study, in which (13) reported that older participants were less afraid and more accepting of death as a reality and as an escape than younger participants. In that study, females were also significantly more accepting of life after death and more accepting of death as an escape than males. These findings may surprise since other studies show, that for example gender or prior experience with death have an influence on attitudes towards dying and death (43, 44). For instance, woman have a more positive attitude towards death (45). This findings seems to be related to a general difference between men and women in their perceptions of health (46) and it may also surprise as other studies show that according to students’ opinions, death education plays an important role in Undergraduate Palliative Care Education (UPCE) to achieve a positive self-estimation in competence and self-efficacy (47-52).

In our German sample, the confirmatory factor analysis showed a good fit of the data to the original factor structure with minor adjustments allowing item covariations among Items 2 and 18 due to linguistic similarities. Although the fit was perfectly acceptable, Item 1 did not load highly in any of the factors, thus our results may suggest to rethink the elimination of this item.

Limitations

Besides the significant results, there are some limitations we ought to mention. The measurement only offers a quantitative approach to the field of attitudes towards death. For more in-depth results, qualitative studies (e.g. interviews, focus groups) could be more suited. Sometimes, qualitative studies may not only help to deepen the understanding of the field in study, but also validate existing quantitative results (53, 54).

With regards to the aim to validate this measurement for the use in Palliative Care settings it could be noted that the investigation of the test goodness criteria has not been established with Palliative-Care patients. On the one hand, it is difficult to recruit a comparable sample of Palliative-Care patients in the same time frame, on the other hand the researchers picked medical students, since UPCE became mandatory in Germany during the last years. Furthermore, medical students are particularly interesting, since they are in a unique transition state between being part of the general public and becoming medical professionals (44).

Further studies are desirable in order to examine the construct validity of this German version of the DAP-R (DAP-R-GR). Due to the very limited and complex existing measurements in German language that might be related to death attitude, the construct validity analysis was ruled out for the objectives of this study. Our research group is currently applying the German Version of the DAP-R (DAP-R-GR) via the discourse project website “30 Gedanken zum Tod”, funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). (55) Until today (5/2018) over 1200 individuals participated online. This project is ongoing and data from the survey will be reported separately in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, the limitation and absence of existing measures to capture attitudes towards dying and death in German language has led to the translation and adaption of the Death Attitude Profile-Revised (DAP-R) (13). The German Version of the DAP-R (DAP-R-GR) promises to be a robust instrument to establish normative data on death attitudes for the use in German speaking countries.

Abbreviations

DAP-R-GR: German Version of the Death Attitude Profile-Revised; DAP-R: Death Attitude Profile-Revised; TMT: Terror-Management-Theory; MMT: Meaning-Management Theory; G1-3: target language versions (German); SL: source language version; TL: target language version; B1-3: back-translation versions; FB: preliminary final version of DAP-R-GR; UPCE: Undergraduate Palliative Care Education; BMBF: Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics committee of the Heinrich Heine University (No. 4921R/ Reg-ID: 2014123063). Participants consented to participate in the study and consented that results are published according to the ethical approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving Human Subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Data and material of this study will be made available on the public platform researchgate.net.

Authors’ contributions

JJ and CS designed the study, supervised the translation progress and the consensus panel, supervised data collection, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

NE and DC analysed the data and performed statistical analysis. AS designed the study, and participated in the consensus panel. RF participated in the translation process, participated in the consensus panel and performed language editing. MF and PW supervised the study.

KF designed the study, supervised data analysis, analysed the data, performed statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript.

All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the final version to be published. Each author is taking public responsibility and accepts accountability for those portions of the content they have been substantially involved in as described above.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the students for their participation in the evaluation. The authors thank Manuela Schallenburger, Alexandra Scherg, Collin MacKenzie and Ursula Wenzel-Meyburg for their participation and supportive work in the consensus panel. We also thank Margit van de Snepscheut and Eva Zilkens for their help to realize the survey.

This paper is written in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Medical Research School Düsseldorf for the degree Dr. med. The discourse project: “30 Gedanken zum Tod” was funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF).

Authors’ information

JJ is a specialist registrar in internal medicine at Lukaskrankenhaus Neuss GmbH, Department II, Gastroenterology, Oncology, Internal Medicine and Palliative Medicine, Neuss, Germany. He is a doctoral candidate at the Medical Research School of the Heinrich Heine University, Duesseldorf, Germany.

CSQ is a Consultant in Psychosomatic Medicine, Medical Psychotherapy, and Palliative Medicine from Germany and is a Visiting Lecturer in Palliative Care Psychiatry at the Institute for Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King’s College, London. He is a faculty member of the Global Institute of Psychosocial, Palliative and End-of-Life Care, Toronto, Canada. He is a trainee psychiatrist at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Additionally, he is pursuing a Doctorate of Professional Studies (DProf) in Existential-Phenomenological Psychotherapy at the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling in London, UK.

KF is a Psychologist, freelancing Consultant for Research Methodology and Statistics, Research Associate and PhD student at Witten/Herdecke University, Germany.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

References

- Charta zur Betreung schwertskranker und sterbender Menschen in Deutschland [press release]. Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin e.V., 10/2010 2010.

- Schnell MW, Schulz C. 30 Gedanken zum Tod: mit Fotografien von Olaf Schlotte und einem Vorwort von Klaus Honnef: Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung; 2016.

- Schnell MW, Schulz C. Dem Sterben begegnen: 30 junge Menschen sprechen mit sterbenden Menschen und deren Angehörigen: Hogrefe, vorm. Verlag Hans Huber; 2015.

- Meier EA, Gallegos JV, Thomas LP, Depp CA, Irwin SA, Jeste DV. Defining a Good Death (Successful Dying): Literature Review and a Call for Research and Public Dialogue. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(4):261-71.

- Schulz C. Ängste und Anpassungstörungen. In: Macleod S, Schulz, Christian, editor. Psychiatrie in der Palliativmedizin- Behandlung psychiatrischer und psychosomatischer Probleme am Lebensende. Bern: Hans Huber Verlag; 2013. p. 25-45.

- Nyatanga B, de Vocht Towards a definition of death anxiety. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2006;12(9):410-3.

- Greenberg J. KS, Pyszczynski T., . Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. New York: Gulilford; 2004.

- Schulz C. Angst. In: Schnell MW, Schulz, Christian, editor. Bassiswissen Palliativmedizin. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag; 2012. p. 94-100.

- Wong PTP. Meaning Management Theory and Death Acceptance. In: Adrian Tomer, Grafton T Eliason, Wong PTP, editors. Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes2008.

- Wong PTP. Transformation of grief through meaning: Meaning-centered counseling for bereavement. In: A. Tomer, G. T. Eliason, Wong PTP, editors. Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. p. 375-96.

- Wong PTP. Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In: Batthyany A, Levinson J, editors. Anthology of Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy. Phoenix: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen; 2005.

- Neimeyer RA. Lessons of loss: A guide to coping. London: Brunne rRoutledge; 2001.

- Wong PTP, G.T., Gesser G. Death Attitude Profile-Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes towards death. In: Niemayer RA, editor. Death anxiety Handbook: Research, instrumentation, and application. Washington, DC: Taylor& Francis; 1994. p. 121- 48.

- Bakan D. Disease, pain and sacrifice: toward a psychology of suffering. Boston: Beacon Press; 1971.

- Becker E. The denial of death. New York: Free Press; 1973.

- Marshall VW. Last chapters: A sociology of aging and dying. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1980.

- Wong PTP. Meaning Making and the positive Psychology of Death acceptance. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2010;3(2).

- Neimeyer RA, Wittkowski J, Moser RP. Psychological research on death attitudes: an overview and evaluation. Death studies. 2004;28(4):309-40.

- Abdel-Khalek AM. Comparison of death anxiety in two groups tested during and after (1986 and 1991) the Lebanese Civil War. Psychological reports. 2006;98(3):712-4.

- Feifel H. The Meaning of Death: New York, Blakiston Division, Mcgraw-Hill; 1959.

- Feifel H, Nagy VT. Another look at fear of death. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1981;49(2):278-86.

- Schulz-Quach C. The Nakedness of the Dead Body – the meaning of death to health care professionals working with the dying. Existential Analysis 2018;29(2).

- Wittkowski J. Fragebogeninventar zur mehrdimensionalen Erfassung des Erlebens gegenüber Sterben und Tod (FIMEST). . Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1996.

- Klug A. Einstellungen zu Sterben, Tod und Danach 2014 [Available from: http://klug-md.de/test/festd/festd_sterben.htm.

- Klug A. Einstellungen zu Sterben, Tod und Danach. . Aachen: Verlag Mainz; 1997.

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1993; 46, Issue 12, Pages 1337-1452 (12):1337-452.

- Munet-Vilaró F. Reliability issues of the family environment scale for cross-cultural research. Nursing research. 1990;51:26-32.

- Gjersing L, Caplehorn, J., & Clausen, T. Cross-cultural adaption of research instrumenst: Language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10.

- Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Methodological Issues in Nursing Research; Instrument translation process: a methods review. Journal of advanced nursing, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2004.

- Sundborg E, Törnkvist Lena, Wändell Per, Saleh-Stattin Nouha. Cross-cultural adaption of an Intimate Partner Violence Questoinaire. Clinical Nursing Research. 2012;21:450.

- Hendricson WD RI, Jacobson JM, Rogan H, Bishop GD, Castillo R. Development an initial validation o f a dual language English-Spanish format for the Arthtritis Impact Measurement Scales. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1153-9.

- Bühner M. Einführung in die Test-und Fragebogenkonstruktion. 3 ed: Pearson Deutschland GmbH; 2010.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods. 2007;39(2):175-91.

- Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis: Psychology Press; 2013.

- Arbuckle J. Amos (Version 22.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: IBM SPSS; 2013.

- Bollen KA. A New Incremental Fit Index for General Structural Equation Models. Sociological Methods & Research. 1989;17(3):303-16.

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of psychological research online. 2003;8(2):23-74.

- Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological methods. 1998;3(4):424.

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage focus editions. 1993;154:136-.

- Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of educational research. 2006;99(6):323-38.

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research: Guilford Publications; 2006.

- Auf dem Weg zur Gleichstellung- Bildung, Arbeit und Soziales –Unterschiede zwischen Frauen und Männern [press release]. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt2014.

- Asadpour M, Sabzevari L, Ekramifar A, Bidaki R. The attitude of medical students toward death: A cross-sectional study in Rafsanjan. Indian Journal of Palliative Care. 2016;22(3):354-61.

- Jansen J, Scherg A, Schulz C, Lindblad A. Searching for a good death: A review of medical students’ perceptions. In: Beckers T, Siegers P, editors. Boundaries of Life and Changing Conceptions of Birth and Death – Social and Political Contexts of Assisted Reproduction and Assisted Dying. International Library of Ethics, Law, and the New Medicine: Springer; 2017.

- Palumbo E. Influence of Positive and Negative Death Attitudes on Medical Students’ Empathy and Attitudes Toward End-of-Life Care: PHILADEPHIA COLLEGE OF OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY; 2015.

- Meffert C, Stossel U, Korner M, Becker G. Perceptions of a good death among German medical students. Death Stud. 2015;39(1-5):307-15.

- Karger A, Scherg A, Schmitz A, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Raski B, Vogt H, et al. A Pilot Study on Undergraduate Palliative Care Education – A Study on Changes in Knowledge, Attitudes and Self-Perception. Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine. 2015;5(6).

- Scherg A, Vogt H, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Schmitz A, Schulz C. What is the published evidence on undergraduate medical students´ values on the topic of palliative care education? – A qualitative metasynthesis.

- Schulz C, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Karger A, Scherg A, In der Schmitten J, Trapp T, et al. Implementation of palliative care as a mandatory cross-disciplinary subject (QB13) at the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich-Heine-University Dusseldorf, Germany. GMS Zeitschrift fur medizinische Ausbildung. 2015;32(1):Doc6.

- Scherg A, Vogt H, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Schmitz A, Schulz C. What is the published evidence on undergraduate medical students´ values on the topic of palliative care education? – A qualitative metasynthesis. 2016.

- Fetz K, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Schulz-Quach C. Validation of the German revised version of the program in palliative care education and practice questionnaire (PCEP-GR). BMC Palliative Care. 2017;16(1).

- Schulz-Quach C, Wenzel-Meyburg U, Fetz K. Can elearning be used to teach palliative care?–medical students’ acceptance, knowledge, and self-estimation of competence in palliative care after elearning. . BMC medical education. 2018;18(1).

- Mayring P. Combination and Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis. 2001. 2001;2(1).

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):112-33.

- 30 Gedanken zum Tod Düsseldorf/Witten2017 [cited 2017 22.01.2017]. Available from: http://www.30gedankenzumtod.de/fragebogen/.

Cite

Jansen, J., Schulz-Quach, C., Eisenbeck, N., Carreno, D. F., Schmitz, A., Fountain, R., Franz, M., Wong, P. T. P., Fetz, K. (2019). German Version of the Death Attitudes Profile- Revised (DAP-R-GR) – Translation and validation of a multidimensional measurement towards death. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 61. DOI: 10.1186/s40359-019-0336-6.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.