The 1952 classic film Ikiru is considered Akira Kurosawa’s greatest directorial achievement. The title literally means to live. It is a story about how to live in the face of impending death. It is a dark but life-affirming film, providing a compelling case of existential positive psychology (EPP; Wong, 2009) by exposing the dark side of human existence to awaken us to the potential of authentic meaning and happiness.

Ikiru does not give viewers any cinematic elevation (Niemiec & Wedding, 2008); in fact, it is disconcerting and depressing. Yet, in a curious way, Ikiru leads us through an uplifting existential journey of the protagonist’s self-discovery and personal redemption.

The Cinematic Achievements of Ikiru

The universal story line of Ikiru is bolstered by exceptional directing and performance. The film has two parts. The first part addresses the subjective struggles of the main character, Watanabe, and his quest for meaning. It begins with a narrator who informs us that Watanabe has been diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer. The narrator wonders whether the protagonist has simply passed his time without living his life.

Watanabe’s downcast eyes reveal the dark deadness on the inside. He is all alone behind his desk, going through the same slow, mechanical motions of stamping papers with his official rubber stamp. When the film cuts to his home scene, he is kneeling before the family altar dedicated to his deceased wife. The film then picks up on his failure to reconnect with his estranged son and his subsequent explorations for meaning.

The second part begins with the narrator announcing Watanabe’s death and funeral wake. This segment consists of flashbacks of people describing how their lives have been affected by Watanabe’s final self-sacrificial act of creating a park from a cesspool. Their testimonies validate the transformation of Watanabe foreshadowed at the end of Part 1. The film ends with an epilogue.

Takashi Shimura plays Watanabe perfectly. His unspoken words speak volumes. It is all in the eyes: the grief, the pain, and other deeply felt emotions. His every move is precise. He walks slowly, with his shoulders slumped and his body stooped and stiff. His transformation in the last six months of his life is equally compelling.

The Existential Quest for the Good Life

The doctor who examines Watanabe’s test results asks a pointed existential question: “What would you do if you only have six months left to live?” Ikiru affirms that regardless of how hopeless the situation, one still can lead a fulfilling life, but there are important lessons to be learned.

The Duality Principle

Inasmuch as we hate suffering and fear death, these existential givens are essential for human flourishing. It takes the terror of death for one to discover the beauty of life; it takes adversity to discover one’s strengths. Watanabe finds peace and happiness in the darkest moments of his life. A disillusioned writer whom he meets at a bar points out the important duality principle: “I realize what they say about the nobility of misfortune is true because misfortune teaches us the truth. Your cancer has opened your eyes to your own life. We humans are so careless. We only realize how beautiful life is when we chance upon death.”

The Imperative of Self-Transcendence

Watanabe learns that neither everyday busyness nor earthly delights can rescue him from his private hell; he needs to discover a mission that is worth dying for. He teaches us that the ontological mode of living can be attained only when one dares to live authentically and yield unconditionally to what life demands of us. Self-transcendence is the key to fulfillment. Viktor Frankl (1984) long ago identified self-transcendence as an indispensable human capacity for meaningful living, especially in trying times.

The Process of the Quest for Meaning

Ikiru shows us the process of transforming the terror of dying of cancer into the triumph of authentic living. This process entails the following key stages:

The Need for Awakening

It takes an awakening to change the direction of one’s life. It typically involves a sense of enlightenment and conviction to make some fundamental changes in how one lives. The writer advises Watanabe “to be greedy about living” and offers to serve as a guide to Tokyo’s strip joints and dancing halls. But glitz and jazz cannot take the dread from his heart.

Watanabe’s first awakening does not occur until he requests the piano singer at a bar to sing “Gondola no Uta,” a song about the brevity of life and the need to fall in love. He is so moved that tears well up in his eyes. Yes, only love can overcome the terror of death!

His second awakening results from a chance encounter with one of his former coworkers, Toyo, on a busy street. There is instant chemistry between the two. He adores her for her liveliness and spontaneity. She finds him adorable for his kindness and generosity. She tells him that she quit her office job because of boredom. He confesses a similar feeling: “No matter how hard I try, I can’t remember a thing I’ve done in that office over the last 30 years.”

In a traditional feudal society, even a Platonic relationship between an old man and a young woman is not acceptable. His son accuses him of being a degenerate. The office rumor mill kicks into high gear.

Toyo also feels increasingly uncomfortable going out with a man who is old enough to be her father. She wants to discontinue the relationship. He pleads with her to spend one more evening with him: “Everything seems black. No matter how I struggle and panic, there’s nothing to grab hold of, except you. … When I look at you, it warms me up right here” (pointing at his heart). He then reveals his desperate need for meaning: “Before I die, I want to live just one day like you do.”

Toyo tells him of her job at a factory making wooden toys: “Making these, I feel like I’m playing with every baby.” That symbolic connection provides an extra meaning to her work. He looks pensive as he listens. “It’s not too late,” he says and smiles as if a lightbulb has turned on. “No, it’s not impossible. I know that I can do something there. I just have to find the will.”

What a moment of epiphany! He can finally make use of all his existing character strengths, such as persistence and endurance, to do something that really matters.

The Power of Acceptance and Commitment

Death acceptance is a difficult process. From his conversations with the writer and the young woman, it is clear that Watanabe cannot accept death without having truly lived. The turning point comes after discovering his calling—to transform a cesspool into a park.

True death acceptance manifests itself in commitment to action. An act of commitment transforms a tragedy into triumph. Who can forget Watanabe’s unflinching gaze and the mischievous smile on his face when a bully-looking member of the Japanese Mafia threatens him with death if he does not give up his park project in favor of commercial development? People around him do not know what to make of him. They think he is crazy because of his total disregard for his own well-being.

Finding Happiness in the Jaw of Death

Part two of Ikiru reveals the impact of the last five months of Watanabe’s life. During the all-night wake, coworkers and other public officials try to make sense of his remarkable transformation. Finally, they conclude that the only reasonable explanation is that he must have realized that he was dying. The deputy mayor did not even recognize Watanabe at the dedication ceremony of the new park, but most people at the wake, including people from the community, credit Watanabe with its success.

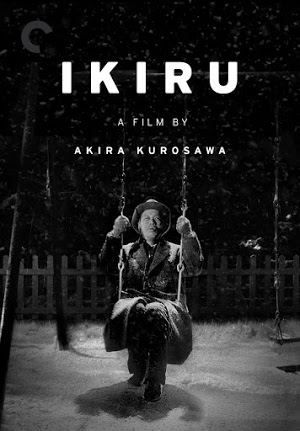

The most revealing information is provided by the police officer who saw Watanabe at the park before he died. The scene at the park is almost magical: Watanabe sitting on the swing alone at night with big snowflakes falling around him. He is happy and serene as he gazes over the playground. He dies in a snowy night without family or friends, without recognition or reward, but at peace with himself.

Conclusion

The film suggests that initially Watanabe’s primary concern is to defend himself against the terror of death (Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Solomon, 1999), but he is able to overcome and transform the fear of death primarily through his quest for meaning. It is difficult to understand his newfound passion for living without recognizing the importance of meaning (Wong, 2007).

Akira Kurosawa has created a moving portrait of the universal human struggle for meaning in a harsh and absurd world. As such, it still resonates today. Everyone can benefit from watching and reflecting on Ikiru. We believe that this film may be particularly beneficial to those who have been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Ikiru can also be used as a teaching tool for psychologists and those in medical professions.

References

- Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Neimiec, R. M. & Wedding, D. (2008). Positive psychology at the movies: Using films to build virtues and character strengths. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber.

- Pyszcynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (1999). A dual-process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death-related thoughts: An extension of terror management theory. Psychological Review, 106, 835-845.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2008). Meaning-management theory and death acceptance. In A. Tomer, G. T. Eliason, & P. T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp. 65-87). New York, NY: Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Existential positive psychology. In S. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 361-368). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., & Gingras, D. (2010). Finding meaning and happiness while dying of cancer: Lessons on existential positive psychology [Review of the film Ikiru]. PsycCRITIQUES, 55(2). doi:10.1037/a0018658