Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacies of the current healthcare system and needs a paradigm change, which is holistic, and community based illustrated by the healing wheel. The present paper proposes that existential positive psychology (PP 2.0) represents a promising approach to meet the rising needs in palliative care. This framework has a twofold emphasis on (a) How to transcend and transform suffering as the foundation for wellbeing, and (b) how to cultivate our spiritual and existential capabilities to achieve personal growth and flourishing. We propose that these objectives can be achieved simultaneously through dialectical palliative counselling, as illustrated by Wong’s integrative meaning therapy (Wong, 2020) and Lo’s Conceptual Model of CALM Therapy in palliative care (Lo et al., 2014). We then discuss existential suffering in general and at the last stage of life in particular; we also review recent research and interventions on existential suffering in palliative patients. Finally, we outline the objectives and the strategies of IMT in providing palliative counselling for palliative care and hospice patients.

(This paper was coauthored with Tim Yu.)

Introduction

COVID-19 has laid bare the inadequacies of palliative care services with over 4 million deaths and 100 million confirmed cases; all health care workers, including palliative care workers, have faced severe challenges, such as shortage of beds, staff, long working hours, and lack of personal protective equipment (Hannon et al., 2021; Oluyase et al., 2021; Pastrana et al., 2021). The Toronto palliative care situation illustrates the need to integrate palliative care into COVID-19 management, and to optimize it for the pandemic (Wentlandt et al., 2021).

Demographic trends also demand strategic thinking and planning to order to meet the challenge of increased demands for palliative care because of increased longevity accompanied by an increase in psychological needs, such as meaning for living, will to live, and death acceptance (Araújo et al., 2016; Wong, 1989; Wong et al., 2014). The existential crisis is especially severe for those who are approaching the end of life with cumulative losses in all areas of life.

For end-of-life care, the best “medicine” is compassion: “The word compassion means ‘to suffer with.’ Compassionate care calls physicians to walk with people in the midst of their pain, to be partners with patients rather than experts dictating information to them” (Puchalski, 2001). “We are at our best, when we serve each other”, wrote Byock (2013), one of the foremost palliative-care physicians in the US. He argued that the healthcare system should not be dominated by high-tech procedures and a philosophy to “fight disease and illness at all costs.” To ensure the best possible elder care, we must not only remake our healthcare system, but also move beyond our cultural aversion to thinking about death.

A Holistic Model of Compassionate Care

The current pandemic reminds me (the senior author) of the SARS crisis, which also exposed the inadequacy of a healthcare system based on the well-entrenched bio-medical model. The courage and personal sacrifice of front-line healthcare workers and volunteers in the face of death demonstrated the crucial role of the spiritual dimension, such as compassion, self-transcendence, and existential courage, which was my focus in my keynote on compassion, funded by the medical authority in Hong Kong (Wong, 2004).

By tapping into spiritual resources, my holistic model (See Figure 1) was aimed to improve healthcare services without a corresponding increase in cost. The setting for my speech in Hong Kong – the historical Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital – served as a symbol of a spiritually oriented holistic healthcare. For more than 100 years, Nethersole Hospital earned a reputation of consistently providing compassionate quality care for the residents of Hong Kong; their mission statement was: “To bring Life to Mankind in its fullness through enhancement of Wellness of the Total Person and Compassionate Care of the Sick.”

Figure 1

The Healing Wheel in Holistic Health Care

The above Healing Wheel is still relevant today. First of all, to be one’s best, the healer (the healthcare provider) needs to be spiritually connected with God (or a higher power) and becomes transformed through a set of religious beliefs or rituals. As a spiritually transformed person, she has become a conduit for spiritual blessings. Her love and faith will have an impact on her patients and the healing community. When she works with the patients, she is praying for wisdom, strength, and healing.

Compassionate human encounters in a supportive and caring environment can be a powerful source of healing. For the healers, they find meaning and purpose in serving their God/gods and serving others. For the patients, they rediscover the meaning of hope and love through the compassionate care they have received. For the community, their voluntary acts of altruism and compassion bring blessings not only to the patients but also to themselves (Newman 2020; Sweet, 2021).

Why is Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) Important for Palliative Care

The above holistic healthcare model can be best understood and practiced from the existential positive psychology (EPP) perspective, also known as the second wave positive psychology (PP 2.0) (Wong, 2011), as distinguished from the positive psychology launched by Seligman (1999). The obvious meaning of EPP is that it integrates ultimate concerns of existentialism with the universal desires for happiness and wellbeing emphasized by positive psychology. Thus, by definition, EPP integrates the positive potentials and the dark side of human existence, resulting in resilience and mature happiness. The main thrust of EPP is the positive transformation of life as a whole to complete the circle of wellbeing. (Wong, 2019, 2020a).

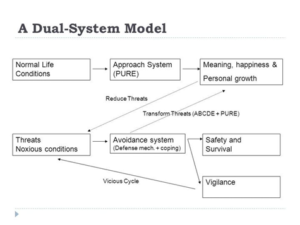

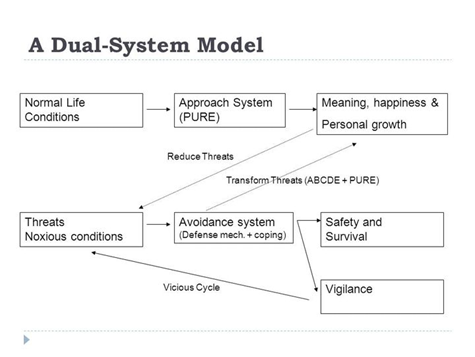

The theoretical and practical implications of EPP are numerous (Wong, 2021). For example, suffering is considered the necessary foundation for wellbeing, and wellbeing can be achieved only through the dialectical process of dual-system model (Wong, 2012a) or Yin-Yang interactions as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

A Dual System Model of What Makes Life Worth Living

This above model explains how the new science of resilience and flourishing through transforming suffering works. Firstly, life is seldom smooth sailing, because of (a) our inherent limitations and foibles, (b) the inevitable suffering at every stage of human development, and (c) external disruptive events, such as the pandemic, wars, and natural disasters. Often, suffering is an inescapable aspect of life. For instance, Salman Akhtar (2014) considers fear, greed, guilt, deception, betrayal, and revenge as the six major sources of suffering, which cannot be eliminated by the medical or cognitive models. Nor can they be eliminated by seeking happiness, because the pursuit itself may be a source of suffering from greed and disappointment. That is why the positive psychology of focusing on the pursuit of happiness does not work, especially during the pandemic.

Secondly, this new paradigm proposes that (a) wellbeing depends on the approach and avoidance systems working together, (b) any setback during the pursuit of happiness will trigger the aversive system, and (c) in coping with inevitable suffering, we are capable of transforming it to strength and joy through personal growth.

Thus, by embracing suffering, the approach system has a better chance of success, and the avoidance system has a better chance of transforming suffering into wellbeing.

From the perspective of existential positive psychology (Wong, 2011, 2019), all emotions, including painful ones, have adaptive value because they help enhance our resilience, meaning, and flourishing. Paradoxically, death holds the key to living a vital, authentic, and meaningful life (Tomer et al., 2008) According to Yalom (2008), although the physicality of death may destroy us, the idea of death has saved many lives. The challenge of PP 2.0 is how to transform death anxiety into death acceptance and a life of significance and mature happiness.

The positive psychology of death anxiety can be best understood in terms of the dual-system model (Wong, 2012a). According to this model, optimal adaptation depends on our ability to confront and transform the dark side of life in service of achieving positive goals. Indeed, the best defense is offense; the most effective way to protect ourselves against the terror of death is to pursue the task of living a meaningful life, despite the shadow of death. Both the approach and avoidance systems are needed to be free us from the prison of death fear and to motivate us to be fully engage with life in whatever little time we have. From this dual-systems perspective, death fear and death acceptance can co-exist and work together for our well-being.

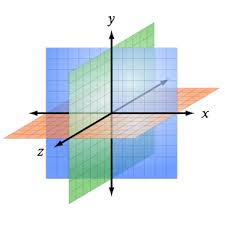

Similarly, this model also proposes that sustainable or mature happiness is based on inner peace, equanimity, and harmony regardless of the circumstances (Wong & Bowers, 2018), as illustrated by Figure 3.

Figure 3

The Central Point of Intersections Represents Inner Peace in the Eye of the Storm

In order to avoid the emotional roller-coaster or getting stuck in the dark pit of painful memories and emotions, the solution is to cultivate spiritual resources to restore an abiding sense of calmness and equanimity. Such mature happiness can be best represented by the central point of intersections of all possible human dimensions both horizontally and vertically. Thus, we can have a sense of joy in all kinds of situation, and regardless of our race, religion, or social-economic status (Robbins, 2021).

This spot is the innermost sacred space of calmness, contentment, attunement, harmonious integration, and spiritual blessings. It is also the center point of a cross, symbolizing the paradoxical truth that one needs to go through Hell to reach Heaven, and one needs to lose oneself in order to find the others (Wong et al., in press). Jesus Christ, Buddha, and Lao-tzu are exemplars of such mature happiness.

A number of palliative therapies are consistent with the dual-process model. For instance, Lo and colleagues’ (2014) conceptual model of Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM) Therapy in palliative care addresses both the psychological stress and the patient’s need for growth and wellbeing simultantiously. Sessions for CALM address both managing illness/symptoms and maintaining a sense of meaning and purpose (Nissim et al., 2012). Reed’s theory of self-transcendence also addresses the need to turn vulnerability to suffering into personal growth and wellbeing through self-transcendence (Abu Khait et al., 2020; Psych-mental health NP, n.d.).

Existential Suffering and Palliative Care

A Developmental Perspective

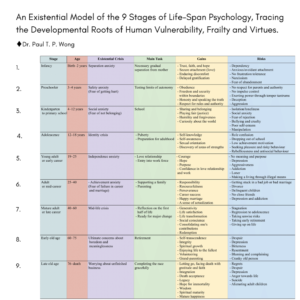

The EPP perspective also enables us to view existential suffering in an entirely new light as shown in Figure 4. Every stage of development, starting with childhood, poses both an existential crisis and opportunity for personal growth. This model complements Erickson’s stage model (Erikson, 1968, 1982) by elaborating the stages of adult development and adding an existential-positive psychology dimension. Thus, life is viewed as a constant struggle in every stage of human development. How we resolve each existent crisis may determine to a certain extent whether we enjoy a life of virtues and flourishing, or lifelong suffering from the evils and negative consequences of the poor choices we’ve made in completing our developmental tasks.

Figure 4

Different Existential Crisis for Different Stages of Human Development

Towards advancing age and death, we resort to spiritual development and self-transcendence to compensate for losses in physical and mental vitality (Reed, 2018; Wong, 1989). Wong et al. (in press) sums up the paradoxical truth of finding meaning in life and death through self-transcendence:

“Living well and dying well involve enhancing one’s sense of self, one’s relationships with others, and one’s understanding of the transcendent, the spiritual, the supernatural…. And only in confronting the inevitability of death does one truly embrace life”

Existential Suffering and the Quest for Meaning

With some imagination, I could hear the cry of “Why” from our ancestors: Why is my child taken by a beast? Why is God angry with by punishing us with natural calamities? Why is life so hard? Why is the point of struggling, because at the end we all die? His cry for meaning has never ceased, because life is full of suffering and existential crises in every era of history, and in every stage of human development.

All people at one time or other have struggled with such existential questions as Who am I? What am I here for? What should I to do with my life? What really matters in my life? How and where can I find happiness? How can I avoid making the wrong choices or life goals? Where do I belong? Where is my home? What is the point of all my striving? Who am I?

For older people, they are more concerns with self-evaluation and regrets (Neimeyer et al., 2011; Ware, 2012; Yalom, 2008). They may ask questions such as: Have I really lived the life I always wanted? Has my life been worthwhile? What is the point of living in pain? What is the meaning of death? What happens to me after I die? How can I find and give forgiveness? How should I best spend the remaining days of my life? How can I find peace, comfort, and hope in the face of death?

Every cry for meaning serves the dual function of making suffering more bearable and finding a purpose for living; thus, making it more likely for us to move towards a life goal in spite of obstacles and suffering. In real life, most people just go about their daily business until they unexpectedly encounter the horrors of human evil, suffering, and death.

The “Why” questions of “Why is life so painful?” will push people to search for a reason or purpose for living. One does not need to understand or use the word “meaning” to live a meaningful life. The reality of life and the human nature conspire to nudge us to search for a deeper and more fulfilling way of life.

Peterson (2018) argued that human beings are by nature religious and spiritual in order to survive in a world full of dangers, evils, and uncertainty. Meaning primarily comes from everyday heroism of taking responsibility for making the necessary sacrifices and aiming at some greater good in the face of widespread evil. Peterson places evil and meaning through the same evolved mechanism of protecting our own vulnerability as finite and fragile human beings in the face of infinite, powerful forces.

If people have not resolved their existential crises in their early stages of development, their existential crisis becomes more intense at the end, as powerfully portrayed in Tolstoy’s (1886/2010) The death if Ivan Ilyich. In the midst of his mental agony and physical pain, Ivan is spiritually reborn in the last hours of his life when he finally realized that his life was not what it should have been. Only after he wants to right the wrong and apologize to his wife, he finds his meaning of life, and his existential suffering disappears. Joy fills his heart before he dies.

Another example is classic film Ikiru by Akira Kurosawa (Wong & Gingras, 2010). In this movie, the protagonist, Watanabe, lives an ordinary life of eating-working-sleeping without reflecting on the meaning of life until cancer strikes. Ikiru shows us the existential journey of transforming the terror of dying of cancer into the triumph of meaningful living. Watanabe’s transformation is shown in his final self-sacrificial act of creating a park from a cesspool and his happy death. The process of his good death began with the agonizing search for meaning after his terminal cancer diagnosis.

According to Frankl (1949/1986), the medical ministry of logotherapy is an adjunct to the practice of medicine. Patients often struggling with such existential questions, such as: Why me? Why now? Why suffering? Why do I have to die in such a young age? Existential suffering results from one’s inability to find a satisfactory answer to the mysteries of evil, suffering, and death.

In view of the complexity of search for meaning to resolve one’s existential crisis, Wong (2020b) proposes a two-factor model of meaning seeking:

“(1) Negatively oriented search for meaning – the Why and How questions that increase our ability to understand the cause and reason of unpleasant & unexpected events in order to meet our needs to predict, control and justify them. It represents the lay scientist and lay philosopher in each of us (Wong 1991; Wong and Weiner, 1981).

(2) Positively oriented search for meaning – the What questions that fulfill our responsibility to do the right thing and pursuing the right life purpose according to our beliefs, conscience, and abilities. It represents the moralist (saint) and idealist (dreamer) in each of us (Frankl 1985; Wong 2016).”

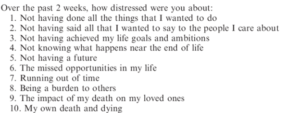

Palliative care patients are wrestling with both the existential problems of suffering and death, and future meaning to fulfill in their remaining days. For example, Figure 5 lists some of the items in Lo and colleagues’ (2011) Death and Dying Distress Scale.

Figure 5

Sample Items from Lo et al.’s (2011) Death and Dying Distress Scale

It is clear from Figure 5 that the search for meaning are mostly negatively oriented meaning seeking, such as regrets for past mistakes and missed opportunities, while some are concerned about unfinished business and seeking future meaning (Items #4 and #5).

In the Patient Dignity Inventory (PDI; Chochinov et al., 2008), the factor on existential distress is primarily concerned with the absence of meaning at the present, such as “Not feeling worthwhile or valued” and “Feeling life no longer has meaning or purpose”, while the factor on peace of mind is concerned with the need for future meaning, such meaningful contribution and spiritual life.

Therefore, the wellbeing of palliative care patients importantly depends on resolving these existential struggles. According to Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being (Peterman et al., 2002), the three factors in the Spiritual Wellbeing subscale essentially depict mature happiness in terms of inner peace and harmony, because of spiritual beliefs, faith, reasons for living, and a sense of purpose.

The Desire to Hasten Death and Physician-assisted Suicide

This represents the latest existential issue as physician-assisted suicide gains increasing acceptance. Progress in medicine and technology makes it possible for people to live longer in spite of unbearable suffering and major losses in functionality and all life domains; theoretically, people could be kept alive almost indefinitely, but at what cost economically and psychologically? Researchers are beginning to ask whether life is still worth living at 100 years or older (e.g., Araújo et al., in press). The medical profession is also debating whether physician assisted suicide should be granted to individuals with mental disorders (Kim & Lemmens, 2016) or physically disabilities (Bikenbach, 1998).

However, research research shows that existential beliefs and inner resources (Araújo et al., 2016) can all contribute to wellbeing even at advanced age. In addition, numerous psychological factors can sustain life, even in harsh conditions, such as meaning (Frankl, 1949/1986), and valuation of life (Lawton et al., 2001). It is our belief that good palliative care should include palliative counseling, which deals with psychological and spiritual issues related to suffering and dying, such as religious beliefs (Puchalski & Guenther, 2012; Wong et al., 2018)

Wong & Stiller (1999) provided a great deal of information supporting good palliative care as an alternative to euthanasia. They cited Byock (1994) as proposing: “we must tell the stories of our patients who have died well, especially those who had previously considered or who might have committed suicide” (p. 6). Joni Eareckson Tada (1992) is such an example. She was a quadriplegic for almost thirty years as a result of a traffic accident. She stated that her ability to minister to others in pain and suffering provided meaning in her life: “The longer I hung in there through the process of suffering, the stronger the weave in the fabric of meaning” (p. 85). Kübler-Ross (1969/1997) also has much to say on physician- assisted suicide:

“Even with all my suffering I am still opposed to Kevorkian, who takes people’s lives prematurely simply because they are in pain or are uncomfortable. He does not understand that he deprives people of whatever last lessons they have to learn before they can graduate. Right now I am learning patience and submission. As difficult as those lessons are, I know that the Highest of the High has a plan. I know that He has a time that will be right for me to leave my body the way a butterfly leaves its cocoon. Our only purpose in life is growth.” (p. 281)

Recent Research on Existential Anxieties and Wellbeing in Palliative Patients

Research in recent years, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, has illuminated the existential anxieties that palliative care patients face on the daily basis as they approach the end of life. It is clear that these anxieties are multifaceted (Gaignard & Hurst, 2019), and the source of much suffering (Hendrie, 2019). They still remain a neglected area in palliative care research, especially in everyday palliative care conversations (Tarbi et al., 2020).

The level of distress that palliative care patients experience as a result of existential anxieties may be influenced by numerous factors. For example, less distress is associated with older age (Lo et al., 2010), higher spiritual wellbeing (Benard et al., 2017; Lo et al., 2011), attachment security (Lo et al., 2009; Vehling et al., 2019), and meaning in life (Bernard et al., 2017). However, previous research has suggested that most if not all palliative care patients, as well as their families and care providers, all experience some form of existential anxieties (Albinsson & Strang, 2003; Barnett et al., 2019; Hendrie, 2019). Some of these anxieties will now be discussed.

Death-related Anxieties

Death-related anxieties range from practical fear (e.g., process of dying, being a burden to their caregivers and family) to psychosocial or existential fears (e.g., missed opportunities, impact or burden of death on others). Vehling et al. (2017) found that between all the different death and dying related fears within the 15-item Death and Dying Distress Scale (DADDS; Krause et al., 2015), fear of “running out of time” was found to be a central concern for palliative care patients. Death-related anxieties are often positively associated with demoralization, characterized by feelings of hopelessness, the loss of meaning, a sense of failure, and meaninglessness (An et al., 2018); and negatively associated to social relatedness (Vehling et al., 2019).

Grief

There are many forms of grief in palliative care settings. As Moon (2013) notes, “Grief and palliative care are interrelated and perhaps mutually inclusive. Conceptually and practically, grief intimately relates to palliative care, as both domains regard the phenomena of loss, suffering, and a desire for abatement of pain burden.” (p. 19). For instance, COVID-19 lockdown procedures, which prevents families from seeing loved ones in palliative care, has led to an increase of anticipatory, disenfranchised, and complicated grief for individuals, families, and medical providers (Wallace et al., 2020). Families taking care of children that are in Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) experience anticipatory grief, grief around the time of death, and grief after death (Schuelke et al., 2021). Patients may have lost their spouse before or during palliative care, leading to feelings of numbness, shock, fear, anger, and survivor guilt (National Institute on Aging, n.d.).

Isolation and Loneliness

As a result of their spouse’s death, as well other factors such as independent living, decline in motor or cognitive abilities, or the recent COVID-19 pandemic, palliative care patients often experience feelings of isolation or loneliness (Mah, 2019; Nyatanga, 2017; Wu, 2020). Abedini and colleagues (2020) found that older individuals who are lonely are more likely to have more illness symptoms (e.g., be troubled by pain, difficulty breathing, or severe fatigue), to use life support in the last 2 years of life, and to die in a nursing home. In their survey across four long term care settings, Sundström and colleagues (2019) reported that in home and residential care, the patients’ existential loneliness was focused on life, both the past and present, while in hospital and palliative care, existential loneliness was focused on the patient’s coming death. However, high levels of existential loneliness were reported in all four settings. That is why some researchers suggest that now is the time to implement community-hospice settings to help decrease mental health problems that are the result of loneliness. (Trivedi et al., 2021).

Dignity Related Existential Distress (DR-ED)

Dignity related existential distress (DR-ED) is prevalent among palliative care patients nearing death for a variety of reasons. Bovero and colleagues (2018) reported that two factors that accounted for 58% of the DR-ED variance in their study are self-discontinuity and loss of personal autonomy. Self-discontinuity may be a result of declining physical and cognitive functions, preventing patients from taking part in meaningful activities. It may also be a result of taking on new responsibilities as the grandparent of a family or elder in the community. On top of physical and cognitive decline, the patient’s loss of independence and personal autonomy may be from the death of their spouse because elderly couples often maintain their independence by compensating for one another (Complete Care Coordination, 2021).

Regrets

Everyone experiences regret from time to time, whether from mistakes or missed opportunities. But experiencing regrets at the end of life may intensify end of life suffering because one knows they will be unable to rectify past mistakes (Neimeyer et al., 2011). In Bronnie Ware’s (2012) bestselling book, she mentioned five common regrets of palliative care patients: wishing that they lived an authentic life, wishing that they didn’t work so hard, wishing they had the courage to express their feelings, wishing that they stayed in touch with their friends, and wishing they let themselves be happier. Many of these regrets come from an “unlived life”, which may play a role in generating end-of-life death-related anxieties (Yalom, 2008).

Integrative Meaning Therapy (IMT) in Palliative Care

Meaning-centered Approach to End-of-life Care

Given the prevalent loss of meaning and dignity in palliative patients, meaning-centered therapies demonstrated efficacy in improving spiritual wellbeing, sense of dignity and meaning, and decreasing depression, anxiety, and desire for death (e.g., Breitbart et al., 2010, 2012; Chochinov et al., 2011). A sense of dignity is defined as “quality or state of being worthy, honored, or esteemed (Webster’s International Dictionary, 1946) is importantly related to personal meaning. Dignity Therapy (Hack et al., 2010) is primarily concerned with what has been meaningful in the life of the patients and the legacy patients wants to pass on to family and loved ones.

Another scientifically validated meaning-centered therapy for advanced cancer is Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (Breitbart & Applebaum, 2011). Its aim is to sustain and enhance a sense of meaning in the face of existential crisis. Based on Frankl’s logotherapy, the protocol of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (Breitbart & Poppito, 2014a, 2014b) is composed of 7-8 sessions in which patients reflect on the concept of meaning and the impact that cancer has produced on their life and identity.

Breitbart’s Meaning-Centered Group Therapy for Cancer Patients (Breitbart et al., 2004) aims to help expand possible sources of meaning by teaching the philosophy of meaning, providing group exercises and homework for each individual participant, and by open-ended discussion. The 8 group sessions are categorized under the following specific themes of meaning relevant to cancer patients:

Session 1 – Concepts of meaning and sources of meaning

Session 2 – Cancer and meaning

Session 3 & 4 – Meaning derived from the historical context of life

Session 5 – Meaning derived from attitudinal values

Session 6 – Meaning derived from creative values and responsibility

Session 7 – Meaning derived through experiential values

Session 8 – Termination and feedback

Wong’s Pioneering Work on Death Acceptance

Wong’s integrative meaning therapy is based on his pioneer work on death acceptance.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ (1969, 2009) stage-model of coping with death (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance) was a milestone in death studies. About 30 years later, Wong and his associates did a comprehensive research on death acceptance, which led to the development of the Death Attitudes Profile (DAP) (Gesser, Wong, & Reker, 1987-88) and the Death Attitudes Profile Revised (DAP-R) (Wong, Reker, & Gesser, 1994). Both scales have been widely used worldwide.

In addition to death fear and death avoidance, Wong and associates identified three distinct types of death acceptance: (1) neutral death acceptance—accepting death rationally as part of life; (2) approach acceptance—accepting death as a gateway to a better afterlife; and (3) escape acceptance—choosing death as a better alternative to a painful existence.

Approach acceptance is rooted in religious/spiritual beliefs in a desirable afterlife. To those who embrace such beliefs, afterlife is more than symbolic immortality, thus offering hope and comfort to the dying as well as the bereaved. Escape acceptance is primarily based on the perception that death offers a welcome relief from the unbearable pain and meaninglessness of staying alive. The construct of neutral acceptance means to accept the reality of death in a rational manner and make the best use of the limited time on earth.

Approach acceptance may also incorporate neutral acceptance with regard to making the best use of our finite life on earth, but it has the advantage that belief in an afterlife can be a source of comfort and hope in the face of death. May be that is why most people believe in heaven or an afterlife (Bethune, 2013).

Consistent with Wong’s dual-system model, death anxiety and death acceptance can co-existence. Some form of death anxiety is always present over a wide range of things, such as ultimate loss, fear of the pain and loneliness in dying, fear of failing to complete one’s life work, the uncertainty of what follows death, annihilation anxiety or fear of non-existence, and worrying about the survivors after one’s death. Even with the constant presence of some level of death anxiety, one can achieve death acceptance through 3 stages: (1) Avoiding death, (2) Confronting or facing death, and (3) Accepting or embracing death.

Meaning Management and Death Acceptance

Meaning plays an important role in death acceptance, because once one has found something worth dying for, one is no longer afraid of death. Meaning-making can help us rise above fear of death and motivates us to strive towards something that is bigger and longer lasting than ourselves. Personally, I (the first author) have gone through the same existential struggles of finding meaning when coping with cancer (Wong, 2018) and loneliness during hospitalization (Wong, 2015).

Wong has described the meaning management theory (MMT; Wong, 2008) as a conceptual framework to understand and facilitate death acceptance. MMT is based on the existential positive psychology and dual-system model described earlier. According to MMT, it is more productive and fulfilling to courageously and honestly confront our death anxiety and at the same time passionately pursue a meaningful goal (Tomer et al., 2008; Wong & Tomer, 2011).

MMT is more than cognitive reframing or rationalization. It actually requires a fundamental shift to from pleasure-seeking to the meaning mindset (Wong, 2012b), from self-centeredness to self-transcendence (Wong, 2016a). Meaning therapy (Wong, 2010, 2012c) equips people to squeeze out meaning and hope from even the darkest moments of life.

Some Key Concepts of IMT in Palliative Care

In addition to helping palliative care patients work through their suffering and come to the point of death acceptance through meaning seeking, we want to briefly explain (1) the concept of meaning, (2) the importance faith, hope, and love, (3) the importance of courage, acceptance, and transformation, and (4) provide a few practical tips for palliative care workers (for details regarding IMT, please read Wong, 2020c):

- Wong’s Definition of Meaning. Meaning has been defined by different researchers different. Wong (2010) proposes that a comprehensive way to clarify the concept of meaning is PURE (purpose, understanding, responsibility, and enjoyment):

- A meaningful life is purposeful. We all have the desire to be significant, we all want our life to matter. The intrinsic motivation of striving to improve ourselves to achieve a worth goal is a source of meaning (remember the movie Ikiru?). That is why purpose is the cornerstone for a meaningful life. Even if you want to live an ordinary life, you can still do your best to improve yourself as a good parent, spouse, neighbor, or a decent human being.

- A meaningful life is understandable or coherent. We need to know who we are, the reasons for our existence, or the reason or objective of our actions (Antonovsky, 1987). Having a cognitive understanding or a sense of coherence is equally important for meaning.

- A meaningful life is a responsible one. We must assume full responsibility for our life or for choosing our life goal. Self-determination is based on the responsible use of our freedom. This involves the volition aspect of personality. That is why for both Frankl (1946/1985) and Peterson (2018) noted that responsivity = meaning.

- A meaningful life is enjoyable and fulfilling. It is the deep life satisfaction that comes from having lived a good life and made some difference in the world. This is a natural by-product of self-evaluation that “my life matters”.

Together, these four criteria constitute the PURE definition of meaning in life. Most meaning researchers support a tripartite definition of meaning in life: comprehension, purpose, and mattering (George & Park, 2016; Martela & Steger, 2016), but these elements are predicated on the assumption that individuals assume the responsibility to choose the narrow path of meaning rather than the broad way of hedonic happiness.

In the existential literature, freedom and responsibility are essential values for an authentic and meaningful life (In addition to Frankl, you can also read Rollo May, Irvin D. Yalom, Emmy van Deuzen, etc). For instance, my (the first author) life is meaningful because I chose the life goal of reducing suffering, as well as bringing meaning and hope to the suffering people. This was not an easy choice, but it was the only choice if I wanted to be true to my nature and my calling.

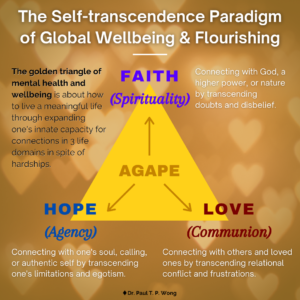

- The Golden Triangle of Faith, Hope, and Love: We have a serious mental health crisis because we are like the fish out of water, living in a materialistic consumer society and a digital world without paying much attention to our spiritual needs. Technological progress contributes to our physical wellbeing, but it also destroys the soul if we do not make an intentional effort to care for our soul.

IMT aims to helps people get back into water—to meet people’s basic psychological needs for loving relationships, a meaningful life, and faith in God and some transcendental values as shown in the symbol of the Golden Triangle (Figure 6).

Figure 6

The Golden Triangle

Briefly, faith in God or a higher power represent our spiritual core value:

- The power of IMT is derived from faith – faith in a better future, in the self, in others, and in God and in a happy afterlife. It does not matter whether you have faith is Jesus, Buddha, or in your medical doctors. If you have faith in someone or something greater than yourself, you will have a better chance of overcoming seemingly insurmountable problems. Faith, nothing but faith, can counteract the horrors of life and death. For Frankl, faith is the key to healing:

“The prisoner who had lost faith in the future – his future – was doomed. With his loss of belief in the future he also lost his spiritual hold; he let himself decline and become subject to mental and physical decay.” (Frankl, 1946/1985, p. 95)

- Hope represents the one’s role as an agent to discover one’s true calling and works towards a better future. Even palliative care patients can work towards a better tomorrow. The saddest thing my (the first author) father said to me during my last visit to Hong Kong was “I have no hope. I’m going to die soon, and none of my children are interested in taking over my business”. because he had no hope beyond his own personal interest. Tragic optimism (Leung et al., 2021; Wong, 2009a) enables one to transcend such hopelessness.

- Love for others and developing connections indicate that we are always part of a larger whole, and relationships are a major source of meaning of life (Wong, 1998). By withholding love, people perish due to loneliness and meaninglessness.

Do we realize that love is the most powerful force on earth? Do we know that love can give us the strength to endure anything, the courage to face any danger, and the joy to make sacrifices for others?

Faith, hope, and love are as essential to our mental health as air, food, and water are essential to our physical health. This positive triad, as depicted by the golden triangle, has enabled humanity to survive since the beginning of time; it is still essential in overcoming depression, addiction, and suffering, and creating a better future. Wellbeing even in palliative care patients, can be conceptualized in terms of the golden triangle.

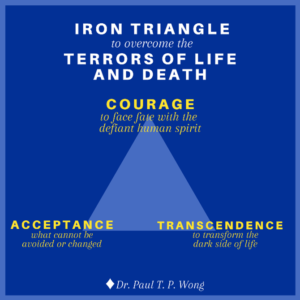

- The Iron Triangle of Courage, Acceptance, and Transformation. Life is tough, especially during old age with all the inevitable losses. During the end-of-life stage, one needs a lot of courage to face all the challenges associated with death and dying (Wong, 2009b). One needs courage to cope with the distress of sickness and dying, to accept all the losses and the final exit. One also needs courage to connect with their own inner resources, family, and community in order to enhance their dignity and well-being.

The main thrust of my (the first author) recent book (Wong, 2020d) is that we are wired in such a way that our genes and brain have the necessary capacities to survive and thrive in any adverse situations, provided that we are awakened to our spiritual nature and cultivate our psychological resources. In addition to the golden triangle, our other resources come from the iron triangle of courage, acceptance, and transcendence as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7

The Iron Triangle

- Existential courage is the courage “necessary to make being and becoming possible” (May, 1975, p. 4). As discussed earlier, existential courage is needed in all stages of human development: The courage to embrace the dark side of human existence makes it possible for us make positive changes, to face what cannot be changed or is beyond our control, and to transform all the setbacks and obstacles.

The most comprehensive treatment of courage can be found in Yang et al. (2010). They treat courage as a spiritual concept “similar to the existential thoughts of the will to power” (p. 13). In their words, “To Adler, the will to power is a process of creative energy or psychological force desiring to exert one’s will in overcoming life problems” (p. 12). Courage is also similar to Frankl’s (1946/1985) defiant power of the human spirit.

Courage unleashes the hidden strength and optimism in us to forge ahead in spite of the dangers, obstacles, and sufferings; courage is an attitude of affirmation, of saying “Yes” no matter what, an attitude that has been steeled by prior experience of overcoming adversities and hardships (Wong & Worth, 2017).

Existential courage consists of the courage to be true to oneself (authenticity), the courage to belong to a group or serve others (horizontal self-transcendence), and the courage to believe and trust in God or a higher power. Such existential courage encompasses the three vital connections covered by the golden triangle. In sum, courage is a matter of the heart and the will. It is an attitude of affirmation and optimism that enables one to have the true grit to faces whatever life will throws at one.

- Death acceptance is the other side of life acceptance. David Kuhl (2003) writes:

“Do I embrace life, or do I prepare to die? And for all of us, the answers are ultimately similar. Living fully and dying well involve enhancing one’s sense of self, one’s relationships with others, and one’s understanding of the transcendent, the spiritual, and the supernatural. And only in confronting the inevitability of death does one truly embrace life.”

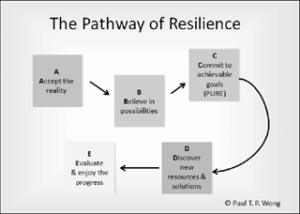

Figure 8

The Pathway of Resilience

The pathway towards resilience is shown in the Figure 8 and explained in Wong (2016b). Acceptance is also the first step in facing death anxiety. We are more likely to embrace life, only when we recognize the spiritual values in the life- death cycle, celebrate the completion of our life’s mission, and live life to the fullest right up to the final moment. There are actually different levels of acceptance: cognitive, emotional, realistic, existential, and transformative. Death acceptance can transform our life only we accept level at the deepest existential level.

(c) There are different pathway ways in transforming negative events and emotions into wellbeing (Wong, 2017. Wong et al., 2006). Transformative coping takes on different forms, such as reframing, re-authoring, or recounting one’s life event in terms of a larger narrative or meta-story. For palliative care patients, life review or reminiscence (Wong & Watt, 1991) and small self-transcendental acts as shown in Ikiru seems most helpful. In life review, we ask patients to reflect on the following questions: What are your happiest moments (with someone special in your life)? What is your best early memory? What are your proudest moments (for your achievement and contribution)? or What are your most meaningful moments?

- Some Practical Tips in Palliative Counselling

Here are some practical tips to help transform a victim’s journey into a hero’s adventure and discover meaning and hope in boundary situations. IMT seeks to awaken the client’s sense of responsibility and meaning, and guide them to (a) achieve a deeper understanding of the problems from a larger perspective and (b) discovering his or her true identity and place in the world

The transformative approach to spiritual care is based on what you say and do with patients rather than what you do to the patients. “Serving patients may involve spending time with them, holding their hands, and talking about what is important to them” (Puchalski, 2001). It often includes the following elements in a healing relationship:

- The healing silence – listening to the inner voice

- The healing touch – touching the heart & soul

- The healing connection – establishing an I-You relationship

- The healing presence – providing a caring, compassionate presence

- The healing process – nurturing spiritual growth

Self-transcendence is a natural way to prepare us for finally transcending our physical self and the material world. Lucas (2014) is correct that self-transcendence is “the best possible help” for palliative care patients because it broadens their values, opens the door for them to discover something worthy of self-transcendence, and it enables them to find meaning and happiness.

Here are a few tips to engage in meaningful or self-transcendental activities:

(1) Do some random acts of kindness to others.

(2) Engage in creative or worthwhile work as a gift to the community or family.

(3) Reach out to get reconciled with estranged loved ones.

(4) Make a useful contribution to society.

(6) Be true to oneself and do something one has always wanted to do.

(7) Construct a coherent life story with photos as a legacy to one’s family.

Encourage them to reflect on the following self-affirmations:

- I believe that life has meaning till I breaths my last my last.

- I am grateful that the reality of suffering and death shows me what I was meant to be.

- I can live a happy and meaningful life until my last breath.

- Life has been very tough, but I am grateful that I have overcome

- I have my regrets, but I have found forgiveness.

Practical tips in spiritual care:

- Show compassion through gentle touch (e.g., holding hand) and smile

- Ask them if there is anything you can do for them

- Ask them about any concerns (e.g., someone they want to see)

- Help them see that they have lived a life of meaning and purpose

- Assure them their life stories are worth telling and remembering

- Assure them they have made a difference in the lives of others

- Assure them they can still have hope beyond death through faith

- Assure them that they can accept death with inner peace

- Offer a prayer if it seems appropriate

Conclusion

“Every society can be best judged by how it treats its vulnerable citizens. The progress of a civilization can be measured not only by technological advancements, but also by progress in the humane treatment of those who cannot help themselves. Therefore, hospice and palliative care represents one of the highest achievements of Christian civilization.” (Wong, 2009b).

To provide high quality end-of-life care, professional healthcare caregivers need to come to terms with personal mortality and have resolved their personal existential struggles regarding the meaning and core beliefs of their own lives. When they are aware of their own calling, personal values, beliefs, and attitudes, they create deeper and more significant connections with their patients (Puchalski & Guenther, 2012).

Spirituality is at the core of palliative care. Religion and spirituality typically pertain to ultimate meaning and purpose, involve certain spiritual practices or religious beliefs and rituals. Some transcendental beliefs (Wong et al., in press) has sense of sacredness (Wong et al., 2018). The quality of palliative care depends on the maturity of the caregiver’s own spirituality. From this point of view, the commitment to the self-care of caregivers and their spiritual development is important. They must become aware of the need to connect first with their source of well-being, peace, and personal harmony, with its own spiritual dimension.

As suggested by the healing wheel, good end-of-life care requires teamwork, which may include physicians, nurses, psychologists, pastoral care chaplains, and the community. When the team uses their collective resources and adopt a holistic approach that recognizes the importance of spiritual-existential dimension in patients and their families, it will benefit both the healthcare professionals and their patients. We need to learn how to open up the inner life to connect with others at the spiritual level and validate eternal values of shared inner lives. The spiritual connection is equally important as medication. Faith in the shared spiritual dimension of relationships can give hope to the dying. Whenever a patient takes their last breath, our focus shifts instantly from the material world to the eternal hope of the soul.

Since we all have to die anyways, we might as well make this last trip the best trip ever, and make our final act the most eloquent statement to who we are and what our lives are all about. To pull this off, we need to start planning now. This may be the best strategy to live and die well.

References

- Abedini, N. C., Choi, H., Wei, M. Y., Langa, K. M., & Chopra, V. (2020). The relationship of loneliness to end‐of‐life experience in older americans: A cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(5), 1064-1071. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16354

- Abu Khait, A., Sabo, K., & Shellman, J. (2020). Analysis and Evaluation of Reed’s Theory of Self-Transcendence. Research and theory for nursing practice, 34(2), 170–187. https://doi.org/10.1891/RTNP-D-19-00015

- Akhtar, S. (2014). Sources of suffering: Fear, greed, guilt, deception, betrayal, and revenge. Routledge.

- Albinsson, L., & Strang, P. (2003). Existential concerns of families of late-stage dementia patients: questions of freedom, choices, isolation, death, and meaning. Journal of palliative medicine, 6(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662103764978470

- An, E., Lo, C., Hales, S., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2018). Demoralization and death anxiety in advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 27(11), 2566-2572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.4843

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). The Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series and the Jossey-Bass health series. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass.

- Araújo, L., Ribeiro, O., Teixeira, L., and Paúl, C. (2016). Successful aging at 100 years: The relevance of subjectivity and psychological resources. Int Psychogeriatr, 28, 179-88. Doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001167

- Araujo, L., Teixeira, L., Afonso, R. M., & Ribeiro, O. (in press). To live or die: What to wish at 100 years and older. Frontiers.

- Barnett, M. D., Moore, J. M., & Garza, C. J. (2019). Meaning in life and self‐esteem help hospice nurses withstand prolonged exposure to death. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(4), 775-780. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12737

- Bernard, M., Strasser, F., Gamondi, C., Braunschweig, G., Forster, M., Kaspers-Elekes, K., Walther Veri, S., Borasio, G. D., & SMILE consortium team (2017). Relationship Between Spirituality, Meaning in Life, Psychological Distress, Wish for Hastened Death, and Their Influence on Quality of Life in Palliative Care Patients. Journal of pain and symptom management, 54(4), 514–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.019

- Bethune, B. (2013, May 7). Why so many people—including scientists—suddenly believe in an afterlife: Heaven is hot again, and hell is colder than ever. Maclean’s. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/society/life/the-heaven-boom/

- Bikenbach, J. E. (1998). Disability and life-ending decisions. Routledge.

- Bovero, A., Sedghi, N. A., Opezzo, M., Botto, R., Pinto, M., Ieraci, V., & Torta, R. (2018). Dignity‐related existential distress in end‐of‐life cancer patients: Prevalence, underlying factors, and associated coping strategies. Psycho-Oncology, 27(11), 2631-2637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.4884

- Breitbart, W., & Applebaum, A. (2011). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy. In M. Watson & D. Kissane (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy in cancer care. (pp. 137-148). Wiley.

- Breitbart, W., & Poppito, S. (2014a). Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A treatment manual. Oxford University Press.

- Breitbart, W., & Poppito, S. (2014b). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A treatment manual. Oxford University Press.

- Breitbart, W., Gibson, C., Poppito, S. R., & Berg, A. (2004). Psychotherapeutic interventions at the end of life: a focus on meaning and spirituality. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 49(6), 366–372.

- Breitbart, W., Poppito, S., Rosenfeld, B., Vickers, A. J., Li, Y., Abbey, J., … Cassileth, B. R. (2012). Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(12), 1304-1309.

- Breitbart, W., Rosenfeld, B., Gibson, C., Pessin, H., Poppito, S., Nelson, C., … Olden, M. (2010). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology, 19(1), 21-28.

- Byock, I. (2013). The best care possible: A physician’s quest to transform care through the end of life. Avery.

- Byock, I. R. (1994). When Suffering Persists …. Journal of Palliative Care, 10(2), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/082585979401000202

- Chochinov, H. M., Hassard, T., McClement, S., Hack, T., Kristjanson, L. J., Harlos, M., Sinclair, S., & Murray, A. (2008). The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. Journal of pain and symptom management, 36(6), 559–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.018

- Chochinov, H. M., Kristjanson, L. J., Breitbart, W., McClement, S., Hack, T., Hassard, T., & Harlos, M. (2011). Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 12, 753-762.

- Complete Care Coordination. (2021). How the death of a spouse can affect the elderly. https://www.completecare.ca/blog/death-spouse-can-affect-elderly/

- Dignity [Def. 1]. (1946). Webster’s international dictionary (2nd ed.). Merriam-Webster.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton.

- Erikson, E. H . (1982). The life cycle completed. Norton & Company

- Frankl, V. (1949/1986). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy. Second Vintage Books.

- Frankl, V. E. (1946/1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press.

- Gaignard, M., & Hurst, S. (2019). A qualitative study on existential suffering and assisted suicide in switzerland. BMC Medical Ethics, 20, 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0367-9

- George, L. & Park, C. L. (2016). Meaning in Life as Comprehension, Purpose, and Mattering: Toward Integration and New Research Questions. Review of General Psychology, 20(3). DOI: 10.1037/gpr0000077

- Gesser, G., Wong, P. T. P., & Reker, G. T. (1987-88). Death attitudes across the life span. The development and validation of the Death Attitude Profile (DAP). Omega, 2, 113-128.

- Hack, T., McClement, S., Chochinov, H. M., Cann, B. J., Hassard, T., Kristjanson, L. J., & Harlos, M. (2010). Learning from dying patients during their final days: Life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy. Palliative Medicine, 24(7), 715-723.

- Hannon, B., Mak, E., Al Awamer, A., Banerjee, S., Blake, C., Kaya, E., Lau, J., Lewin, W., O’Connor, B., Saltman, A., & Zimmermann, C. (2021). Palliative care provision at a tertiary cancer center during a global pandemic. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(5), 2501–2507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05767-5

- Hendrie, D. (2019, January 10). Tackling existential distress in palliative care. News GP. https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/tackling-existential-distress-in-palliative-care

- Kim, S., & Lemmens, T. (2016). Should assisted dying for psychiatric disorders be legalized in Canada?. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, 188(14), E337–E339. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160365

- Krause, S., Rydall, A., Hales, S., Rodin, G., & Lo, C. (2015). Initial validation of the Death and Dying Distress Scale for the assessment of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of pain and symptom management, 49(1), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.012

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1969/ 1997). On death and dying. Scribner.

- Kuhl, D. (2003). What dying people want: Practical wisdom for the end of life. Anchor Canada.

- Lawton, M. P., Moss, M., Hoffman, C., Kleban, M., Ruckdeschel, K., and Winter, L. (2001). Valuation of life: A concept and a scale. Aging Ment Health, 13, 3–31. Doi: 10.1177/089826430101300101

- Leung, M. M., Arslan, G., & Wong, P. T. P. (2021). Tragic Optimism as a Buffer against COVID-19 Suffering and the Psychometric Properties of a Brief Version of the Life Attitudes Scale (LAS-B). Frontiers. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646843

- Lo, C., Hales, S., Jung, J., Chiu, A., Panday, T., Rydall, A., Nissim, R., Malfitano, C., Petricone-Westwood, D., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2014). Managing Cancer And Living Meaningfully (CALM): Phase 2 trial of a brief individual psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Palliative Medicine, 28(3), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313507757

- Lo, C., Hales, S., Zimmermann, C., Gagliese, L., Rydall, A., & Rodin, G. (2011). Measuring death-related anxiety in advanced cancer: preliminary psychometrics of the Death and Dying Distress Scale. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology, 33 Suppl 2, S140–S145. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230e1fd

- Lo, C., Lin, J., Gagliese, L., Zimmermann, C., Mikulincer, M., & Rodin, G. (2010). Age and depression in patients with metastatic cancer: The protective effects of attachment security and spiritual wellbeing. Ageing & Society, 30(2), 325-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X09990201

- Lo, C., Walsh, A., Mikulincer, M., Gagliese, L., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2009). Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: Psychometric properties of a modified and brief experiences in close relationships scale. Psycho-Oncology, 18(5), 490-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1417

- Lucas A. M. (2001). Introduction to the Discipline for pastoral care giving. Journal of health care chaplaincy, 10(2), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1300/j080v10n02_01

- Mah, K. (2019). Existential loneliness and the importance of addressing sexual health in people with advanced cancer in palliative care. Psycho-Oncology, 28(6), 1354-1356. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.5092

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

- May, R. (1975). The courage to create. Bantam Books.

- Moon P. J. (2013). Grief and palliative care: mutuality. Palliative care, 7, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.4137/PCRT.S10890

- National Institute on Aging. (n.d.). Mourning the death of a spouse. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/mourning-death-spouse

- Neimeyer, R. A., Currier, J. M., Coleman, R., Tomer, A., & Samuel, E. (2011). Confronting Suffering and Death at the End of Life: The Impact of Religiosity, Psychosocial Factors, and Life Regret Among Hospice Patients, Death Studies, 35(9), 777-800, DOI: 10.1080/07481187.2011.583200

- Newman, K. M. (2020, March 18). Eight acts of goodness amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/eight_acts_of_goodness_amid_the_covid_19_outbreak

- Nissim, R., Freeman, E., Lo, C., Zimmermann, C., Gagliese, L., Rydall, A., Hales, S., & Rodin, G. (2012). Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully (CALM): A qualitative study of a brief individual psychotherapy for individuals with advanced cancer. Palliative Medicine, 26(5), 713-721. Doi: 10.1177/0269216311425096

- Nyatanga B. (2017). Being lonely and isolated: Challenges for palliative care. British journal of community nursing, 22(7), 360. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.7.360

- Oluyase, A. O., Hocaoglu, M., Cripps, R. L., Maddocks, M., Walshe, C., Fraser, L. K., Preston, N., Dunleavy, L., Bradshaw, A., Murtagh, F., Bajwah, S., Sleeman, K. E., Higginson, I. J., & CovPall study team (2021). The Challenges of Caring for People Dying From COVID-19: A Multinational, Observational Study (CovPall). Journal of pain and symptom management, S0885-3924(21)00159-7. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.138

- Pastrana, T., De Lima, L., Pettus, K., Ramsey, A., Napier, G., Wenk, R., & Radbruch, L. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on palliative care workers across the world: A qualitative analysis of responses to open-ended questions. Palliative & supportive care, 19(2), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951521000298

- Peterman, A. H., Fitchett, G., Brady, M. J., Hernandez, L., & Cella, D. (2002). Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 24(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06

- Peterson, J. B. (2018). 12 Rules for Life: An antidote to chaos. Vintage Canada.

- Psych-mental health NP. (n.d.). Pamela Reed’s theory of self-transcendence. Pmhealthnp.com https://pmhealthnp.com/pamela-reeds-theory-of-self-transcendence/

- Puchalski C. M. (2001). The role of spirituality in health care. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 14(4), 352–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2001.11927788

- Puchalski, C., & Guenther, M. (2012). Restoration and re-creation: Spirituality in the lives of healthcare professionals. Current Opinion in Supportive Palliative Care, 6, 254-258.

- Reed, P.G. (2018). Pamela G. Reed: Self-transcendence theory. In M.R. Alligood (Eds.). Nursing theorists and their work (9th ed.) (pp. 463-476). Mosby Elsevier

- Robbins, B. D. (2021). The Joyful Life: An Existential-Humanistic Approach to Positive Psychology in the Time of a Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648600

- Schuelke, T., Crawford, C., Kentor, R., Eppelheimer, H., Chipriano, C., Springmeyer, K., Shukraft, A., & Hill, M. (2021). Current grief support in pediatric palliative care. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 8(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/children8040278

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1999). The APA 1998 annual report. American Psychologist, 54(8), 537-568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.537

- Sundström, M., Blomqvist, K., Anna‐Karin Edberg, & Rämgård, M. (2019). The context of care matters: Older people’s existential loneliness from the perspective of healthcare professionals—A multiple case study. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 14(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/opn.12234

- Sweet, J. (2021, February 10). How random acts of kindness can boost your health during the pandemic. VeryWell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/how-random-acts-of-kindness-can-boost-your-health-5105301

- Tada, J. E. (1992). When is it right to die? Suicide, euthanasia, suffering, mercy. Zondervan Pub.

- Tarbi, E., Gramling, R., Bradway, C., & Meghani, S. (2020). “If it’s the time, it’s the time”: Existential communication in naturally occurring palliative care conversations with individuals with advanced cancer, their families, and clinicians (RP307). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), 203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.052

- Tolstoy, L. N. (2010). The death of Ivan Ilych. Fair Price Classics (Originally published in 1886).

- Tomer, A., Eliason, G. T., & Wong, P. T. P. (Eds.). (2008). Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes. Erlbaum.

- Trivedi, H., Trivedi, N., Trivedi, V., & Moorthy, A. (2021). COVID-19: The disease of loneliness and solitary demise. Future Healthcare Journal, 8(1), e164-e165. http://dx.doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0154

- Vehling, S., Malfitano, C., Shnall, J., Watt, S., Panday, T., Chiu, A., Rydall, A., Zimmermann, C., Hales, S., Rodin, G., & Lo, C. (2017). A concept map of death-related anxieties in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 7(4), 427-434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001287

- Vehling, S., Tian, Y., Malfitano, C., Shnall, J., Watt, S., Mehnert, A., Rydall, A., Zimmermann, C., Hales, S., Lo, C., & Rodin, G. (2019). Attachment security and existential distress among patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 116, 93-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.018

- Wallace, C. L., Wladkowski, S. P., Gibson, A., & White, P. (2020). Grief During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Palliative Care Providers. Journal of pain and symptom management, 60(1), e70–e76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012

- Ware, B. (2012). The top five regrets of the dying: A life transformed by the dearly departing. Hay House.

- Wentlandt, K., Cook, R., Morgan, M., Nowell, A., Kaya, E., & Zimmermann, C. (2021). Palliative Care in Toronto During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of pain and symptom management, S0885-3924(21)00158-5. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.137

- Wong, P. T. P. (1989). Personal meaning and successful aging. Canadian Psychology, 30(3), 516-525. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079829

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile. In P. T. P. Wong, & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Erlbaum.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2004). Compassionate and spiritual care: A vision of positive holistic medicine. International Network on Personal Meaning. http://www.meaning.ca/archives/archive/pdfs/wong-spiritual-care.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2008). Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In A. Tomer, G. T. Eliason, & P. T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (p. 65–87). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009a). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Tucker & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009b). Compassion: The hospice movement. In G. Kurian (Ed.), The encyclopedia of Christian civilization. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). Meaning therapy: An integrative and positive existential psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9132-6

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 52(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012a). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). What is the meaning mindset? International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 4(1), 1-3.

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012c). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2013, April 15-16). Pastoral care: Imagine the possibilities. (Presented at the 45th annual Alberta pastoral care association conference). http://www.drpaulwong.com/pastoral-care-imagine-the-possibilities /

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015). A meaning-centered approach to overcoming loneliness during hospitalization, old age, and dying. In A. Sha’ked & A. Rokach (Eds.), Addressing loneliness: Coping, prevention and clinical interventions (pp. 171-181). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Self-Transcendence: A Paradoxical Way to Become Your Best. International Journal Of Existential Positive Psychology, 6(1), 9. http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017). Coping and stress. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 886-890). New York, NY: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2018, September 14). Living with cancer, suffering, and death: A case for PP 2.0. (Autobiography, Ch. 27). DrPaulWong.com. http://www.drpaulwong.com/living-with-cancer-suffering-and-death-a-case-for-pp-2-0-autobiography-ch-27/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020a). The maturing of positive psychology and the emerging PP 2.0 [Book review of Positive Psychology (3rd ed.) by William Compton and Edward Hoffman]. International Journal on WellBeing, 10(1). Doi:10.5502/ijw.v10i1.885

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). Meaning and evil and a two-factor model of search for meaning [Review of the essay Meaning and Evolution, by R. Baumeister & W. von Hippel]. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 4(1), 63-67. DOI: 10.26613/esic/4.1.170

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020c). Existential Positive Psychology and Integrative Meaning Therapy. International Review of Psychiatry. DOI: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020d). Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 According to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. Toronto, ON: INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021). Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) and global wellbeing: Why it is Necessary During the Age of COVID-19. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 10(1), 1-16.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., & Yu, T. T. F. (In press). Existential suffering in palliative care: An existential positive psychology perspective. Medicina.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.