Abstract

The unprecedented changes in our society because of COVID-19 and the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) shows that our healthcare system and the medical approach to psychotherapy can no longer meet the mental health needs of society. This paper first described the negative impact of COVID-19 and 4IR on our mental health. Then, following a brief critique of the medical model, this paper proposes that the future of psychotherapy needs to be based on the more inclusive and integrative framework of existential positive psychology (PP 2.0), which emphasizes flourishing through suffering. Finally, the paper emphasizes Viktor Frankl’s cure and Wong’s integrative meaning-therapy. It concludes that integrative meaning therapy represents the future of psychotherapy, because it is situated in the area of interactions of at least three traditions: Clinical psychology, existential psychology, and positive psychology. This integrative model is holistic, recognizing humans as bio-psycho-social-spiritual beings and considers several theoretical perspectives in both diagnosis and treatment.

Our world is like a runaway bullet-train on a collision course, with no one able to stop it. This metaphor captures the general anxiety over losing control of one’s own destiny. It also captures the fear of an uncertain future with all the rapid changes in technology, and social changed decided by the big international corporations and governments. For example, Friedman (2016) pointed out that during twenty-first century, the three largest forces―Moore’s law (technology), the market (globalization), and mother nature (climate change and biodiversity loss)―are all accelerating at a pace beyond the comprehension and control of the average citizen. These accelerations are reshaping all the main domains of life: the workplace, politics, geopolitics, ethics, and community. These changes threaten our sense of control and security. Therefore, we need to slow down, learn from nature, and reimagine life.

According to the Ederman-Trust Survey (Purtill, 2020), there is increasing anxiety about job losses and an economic recession due to automation. Nearly two in three people felt that the technological changes are too fast, and they had no control over the robotic processing automaton technology (RPA; Galer, 2020). The International Data Corporation (IDC; Jyoti & Schubmehl, 2019) also predicted that by 2022, 75 percent of the world place will incorporate some AI and automation. There is mounting concern about job losses.

With the promises of the 5G network and the fourth industrial revolution (4IR), we may have created a society which is too fast and too complicated for our brain to cope. Therefore, we need to pause and ask ourselves: What kind of society de we really that will optimize positive mental health? Are the big businesses really creating a society that meets our deepest human needs? Indeed, it is high time to reimagine a better society and a more effective approach to mental health.

The Negative Impact of the 4IR on Mental Health

According to Klaus Schwab (2018), the 4IR unleashed a series of social, political, cultural, and economic upheavals over the 21st century, and it is “driven largely by the convergence of digital, biological, and physical innovations.” When we recognize all the great challenges ahead, “we can take the steps to align common human values with our technological progress and ensure that the Fourth Industrial Revolution benefits human beings first and foremost.”

Therefore, Schwab called for a vision of a “sustainable foundation for social and economic development, built around shared values of the common good, human dignity, and intergenerational stewardship.” In accordance with Schwab’s call for action, this paper proposes the development of a sustainable foundation for wellbeing and positive mental health, built around shared values, existential concerns, human dignity, and the intrinsic value and meaning of life.

There is serious concern about the negative impact regarding the increasing dependence on technology. Johnson (2020) reported research that discovered overdependence on technologies, such as social media, can negatively affect people, making them feel more isolated, depressed, and anxious.

According to Anderson & Rainie (2018), PEW research showed that many experts were concerned about the harmful effects of too much digital life on children and adults. For example, David Ellis, Ph.D., course director of the department of communication studies at York University in Toronto concluded: “There’s growing evidence these digital addictions are promoting depression, loneliness, video-gaming abuse and even suicidal behavior, especially among teens and young adults.”

According to psychiatrist Samoon Ahmad (2020), work is a necessary part of life. Meaningful work is a necessary part of one’s wellbeing and happiness. Work can endow one with a sense of dignity, significance ,and fulfillment. As work becomes more scare and competitive, many will become unemployed. Thus, people are worried about overwork in order to keep their job, or difficulty of finding steady work after losing their jobs. Those who are unemployed “will likely feel deeply humiliated, lonely, and resentful, and will likely experience many of the well-documented physical and mental health problems currently associated with ‘worklessness’ (hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart attack, anxiety, and depression).” He also urged mental health professionals to” become more attuned to these global phenomena to better understand our patients and their struggles.”

In a highly advanced society, the geek will inherit the earth because individuals without higher education and computer skills will have little chance of getting all the new jobs created by new innovations. People will have difficulty making a living by working with their hands doing factory work, practicing traditional trades such as carpentry, or creating artistic work such as pottery. The 4IR may increase productivity and physical wellbeing at the expense of human dignity. By conceptualizing people as consumers of material good, human beings are nothing but animals or supplicated machines. This will result in dehumanization.

The 4IR has created new kinds of psychological problems, such as Hikikomori (Takano & Wong, in press). This is a new a phenomenon whereby Japanese youth physically withdraw from society and isolate themselves for extended periods of time, staying touch with others virtually. A similar phenomenon can also be found in many Chinese people who spent most of their time surfing the internet, playing electronic games, or indulging in pornography. Many of them developed symptoms of depression and anxiety. They suffer from a sense of shame and guilt because they cannot fulfill their parents’ expectations and feel useless in depending on parental support. This phenomenon happens because parental wealth and the ubiquitous access to the internet makes it possible for young people to live comfortably without having to work and establish relationships, two of the three main ingredients of the golden triangle, which I will discuss later.

Online connectiveness can never replace face-to-face wholistic and authentic relationships. Therefore, no amount of online communication can completely fill the need for real intimacy and genuine trusting relationships. The by-product of social isolation are feelings of emptiness and boredom. Humans are wired for relationships, which are essential for meaning and wellbeing (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; McDonald et al., 2012).

From the perspective of existential positive psychology (Allport, 1981; Frankl, 1985; Peck, 1978/2012; Peterson, 2018; Wong, 2019) human beings are hardwired as religious/spiritual beings in order to survive in a world full of dangers and uncertainty. Meaning and faith primarily come from taking responsibility for making the necessary sacrifices for the common good and worshipping a higher power for protection in coping with all kinds of evils, from pandemics and natural disasters.

All the machine models and animal models fail to recognize the deep-seated human quest for existential meaning. Carrying the logic of the computer model to its extreme would be Yuvah Noah Harari’s controversial book Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (2018); it gives us a chilling future when dataism becomes our new god and our faith will be placed in the power of data processing and algorithms.

Without a higher view of human beings, with its unique spiritual dimension of responsibility and self-transcendence, we will either become apes with dark destructive instincts and a computer-assisted god-like intelligence, or citizens of a totalitarian state that controls every aspect of our thoughts and behaviors with artificial intelligence and robots. In both scenarios, people will feel a loss of human dignity and meaning in life (Wong, 2020a).

A related challenge we face is how to protect our individual freedom and dignity, when we are constantly monitored by ubiquitous face-recognition technology and big-data that collect every aspect of our activities. This is already happening in China, where people are constantly evaluated by the central government and given social credit (Vinayak, 2019), which may determine whether they are free to travel of qualified to apply for certain job.

With the government’s need to control the spread of COVID-19, such monitoring becomes ever more sophisticated and all-encompassing. The central government has so much information on their citizens that some individuals may run the risk of being arrested for making statements or doing things that are considered as subversive. Therefore, we need to consider the ethical implications of violating universal human rights if there is nothing to counteract the abuse of technology (Swart, 2020).

The Challenges of COVID-19

The pandemic has created a mental health crisis through fear of the deadly virus, the lockdown, and social distancing policy. For example, Yong (2020) observed that:

“At a moment of profound dread and uncertainty, people are being cut off from soothing human contact. Hugs, handshakes, and other social rituals are now tinged with danger. People with anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder are struggling. Elderly people, who are already excluded from much of public life, are being asked to distance themselves even further, deepening their loneliness.”

According to the latest update on August 17, 2020 (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020), more than 20 million cases of COVID-19 (in accordance with the applied case definitions and testing strategies in the affected countries) have been reported, including 770 273 deaths. Most heath experts are not optimistic that the pandemic will go away anytime soon, and they are concerned about the second wave of COVID-19 in the fall.

In spite of all their progress in science, technology, and wealth, so many mighty countries have been brought to their knees by the pandemic. COVID-19 has demonstrated in a convincing manner that human beings are defenseless against a steadily evolving, airborne micro pathogen that is capable of killing millions of people. One good thing that comes from this global catastrophe is that COVID-19 reminds us that we are foible and fragile beings.

Prior to COVID-19, we already had a mental health crisis. Suicide rates in the U.S. have increased nearly 30 percent in less than 20 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and prevention. Suicide among people aged 10-24 was the second leading cause of death (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

The medical model of having more psychiatrists, more diagnoses, and more medication has not stopped the rising rates in suicide, drug overdoses, and depression. Therefore, we need to search more broadly for the underlying cultural and social factors that contribute to suicide, overdoses, and depression.

The National Academic Press in Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative (Institute of Medicine et al., 2002) had this to say:

“Society and culture play an enormous role in dictating how people respond to and view mental health and suicide…Cultural variables have a far-ranging impact on suicide. They shape risk and protective factors as well as the availability and types of treatment that might intervene to lessen suicide.”

Given the importance of culture, we need to ask ourselves: Why is addiction primarily a problem with Western affluent societies? My hypothesis is that the pursuit of personal happiness and success may have contributed to our existential crisis of inner emptiness, loneliness, and anxiety–the common factors underlying the current epidemic of addiction, depression, and suicide.

Our cultural obsession with happiness has unwittingly resulted in the “unhappiness epidemic” because of spending too much time on social media and smartphones, according to research by Twenge (2017). In a national study, she found that “teens who spent more than five hours a day online were twice as likely to be unhappy as those who spent less than an hour a day.”

In her book iGen (2017), Twenge shows that those born in the mid-1990’s up to the mid-2000’s spend their entire adolescence on smartphone and social media, contributing to their unprecedented levels of anxiety, depression, and loneliness.

In a similar vein, Brock Bastian’s (2018) book, The Other Side of Happiness: Embracing a More Fearless Approach to Living provides considerable evidence that conforming to the social pressure of pursuing happiness and avoiding pain has created a coddled generation, vulnerable to hardships and mental illness. This generation has experienced the loss of protective factors, such as religion, faith community, or a stable home; increased use of smart-phones and social media, resulting in a decrease in genuine face-to-face relationships; and the lack of psychological preparedness and coping skills for life’s inevitable problems. They also have unrealistic expectations of happiness, beauty, and success. The resulting alienation (loneliness), helplessness, anxiety, hopelessness, and meaninglessness contribute to the epidemic of depression, addiction, and suicide, as predicted by Viktor Frankl (1985).

Therefore, at both the societal and individual levels, to avoid the happiness trap, we need to develop a more realistic life orientation and focus on what really matters in life, such as developing loving relationships, making personal sacrifices for something bigger than oneself, and having faith in a higher power or transcendental values: all protective factors against depression and suicide.

The mental health crisis has gone from bad to worse during COVID-19 because of the lockdown and the daily bad news of rising death toll and the dangers of the pandemic (O’Donnell, 2020, Roy, 2020; Wan, 2020).

Critique of the Biomedical Model of Mental Health

The current mental health system is overwhelmed by the mental health fallout of COVID-19, and its inadequacy of overdependence on psychiatrists and medication has been fully exposed. It is unfortunate that most of the advice from mental health experts is focused on negative emotions, such as depression and anxiety, and they have only mentioned medication and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) as treatment options.

A little reflection would tell us that the existential suffering inflicted by the absurdity of life cannot be explained away by rational thinking. This is especially true during this pandemic. Groundhog Day, filled with bad news about the rising death toll and harsh economic condition, would not go away simply because we can think clearly.

There is nothing new in critiquing the medical model in mental health (Huda, 2019). Szasz (1961) was the first major figure to point out that humans difficulties should be conceptualized as “problems in living” rather than mental illnesses or diseases; therefore, family members, friends, clergymen, and other mental health professionals could all be solicited by or on behalf of those experiencing difficulties adapting to the demands of life (Benning, 2016).

According to Deacon (2013), the biomedical model posits that mental disorders are brain diseases and emphasizes pharmacological treatment. But this approach has not resulted in good mental health outcomes and neglected the biopsychosocial model. In a similar vein, Huda (2019) defended psychiatry as a medical practice, but he also recognized that other perspectives are needed. He preferred a humanistic psychiatric framework for the conceptualization and treatment of mental illness/disease.

The Need for Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0)

I have been working on PP 2.0 since 2010 (Wong, 2010, 2011, 2016a, 2017, 2019). More than ever before, I believe that PP 2.0 provides the most promising path to fulfill the full potentials of both positive psychology and existential psychology for the benefits of individuals and society.

For example, wellbeing is no longer conceptualized as the outcome of positive affect, positive traits, and positive circumstances. Rather, wellbeing is reconceptualized as both the process and the outcome of managing an adaptive balance between pursuing positive goals and overcoming or transforming all the negative forces.

According to PP 2.0, the only kind of sustainable wellbeing is one that has survived trials and tribulations. Therefore, one major task for the new science is to identify the different sources of suffering and their transformation. For instance, Salman Akhtar (2014) considers fear, greed, guilt, deception, betrayal, and revenge as the six major sources of suffering, which cannot be eliminated by the medical or cognitive models. That is why PP 2.0 advocates a new kind of science of flourishing though the gates of suffering (Wong, 2019).

Another character of PP 2.0 is that it demands wellbeing researchers to take into account both the macro factors (such the pandemic, global economic, and systemic discrimination) and micro factors (such as one’s personal demons and limitations).

In other words, individual flourishing is not just a matter of doing all the right thing, but dependent on coping with negative external forces and the collective efforts to improve complicated large systems such as social justice, political freedom, and the human ecology. Properly understood, PP 2.0 links the wellbeing of individuals to the world condition. Consequently, living a better life requires efforts to improve both one’s own life and the world we all live in.

The Need for Viktor Frankl’s Cure and PP 2.0

Viktor Frankl’s name was frequently mentioned during various interviews of mental health experts, typically psychiatrists. A recent biography of Frankl (Pytell, 2020) also attests to the fact the Frankl lives on even in the 21st century. He redefined psychiatry by restoring the spiritual dimension to personhood. Therefore, we have a new bio-psycho-social-spiritual model of mental health and psychotherapy.

His current popularity demands a new interpretation of Frankl’s revolutionary ideals. He redefined psychiatry as a spiritual therapy psychotherapy, which restores human dignity and quest for meaning to the forefront. He advocates that the best way to cope with the suffering and the existential crisis is to embrace the contradictions and paradoxes of life in a hostile world.

The power of Frankl’s ideas comes from the tension between suffering and happiness, freedom, and responsibility, self-transcendence and self-actualization. This is a shift from the simplistic binary view of the world to a dualistic view that everything exists in polarity, and successful adaptation depends on achieving the dynamic balance between two interdependent, opposite dimensions.

Frankl is the most optimistic existentialist. He would react very differently to the coronavirus compared to Albert Camus, who believed that the plague means life–meaningless and absurd. In his story The Plague (1947/2020) Camus’ answer to the arbitrariness of death and the absurdity of life was personal revolt: “Rieux becomes the incarnation of the man in revolt. He continues to fight for his fellow human beings no matter how dire the circumstances or elusive the chance of success.” (Gloag, 2020, p. 60). Dr. Rieux’s dedication to his patients was simply motivated by his moral instinct to save lives against an evil monster in a meaningless and hostile world.

In contrast, Frankl believed that life has intrinsic meaning and our faith in meaning and love can triumph over all evils, including the pandemic. Rarely was a psychiatrist claimed by both the existentialists and positive psychologists as Frankl.

Indeed, COVID-19 has made it impossible to ignore the fact that death and suffering is a big part of life. The world has become a laboratory to test out this new science of resilience and wellbeing through the gates of suffering. My research partners from more than 20 different countries and I are currently conducting a multinational study of how meaning, responsibility, and existential coping can function as a buffer against the adverse effects of COVID-19.

Therefore, for therapy to be effective, we need to help clients give up their victim mentality to become an everyday hero, who has the courage and optimism to accept the absurdity of life as the foundation to create a better future:

“Only to the extent that someone is living out this self transcendence of human existence, is he truly human or does he become his true self. He becomes so, not by concerning himself with his self-s actualization, but by forgetting himself and giving himself, overlooking himself and focusing outward.” (Frankl, 1977/2011, p. 35)

This quantum shift in mindset also means that they no longer regard suffering caused by COVID-19 as a dreadful enemy, but as a warning that their life is out of balance and a signal for them to overcome all their setbacks and find a new path of meaning and purpose.

All kinds of unexpected good things can come from this shift in mindset. According to Frankl (1985), we all have the primary need for transcendental meaning; this is the deepest yearning in our soul, which cannot be satisfied with material things or egotistic goals. We need to discover some value or life goal that is worth dying for.

The Importance of Self-Transcendence

That is why he defined our search for meaning as the search for self-transcendence, for something much greater than ourselves, greater than our own life. Once we are awakened to transcendental values, we become truly alive and fearless. This is when we have discovered our passion for living.

Frankl made the greatest discovery in psychology and psychotherapy–to transform all our suffering into resilience and happiness, it takes willing and joyful suffering for something we love more than ourselves.

For example, I am grateful for all my suffering, which have made me a better person and good psychologist who know how to help others. My suffering also enables me to find my calling which is to bring meaning and happiness to suffering people.

That is why I always find ways to help my clients. Recently, I had a young client (17 years old) who suffered from high levels of anxiety because of COVID-19. Right from the start, I told him, “welcome to the club, because everyone is nervous about the coronavirus, which is capable of infecting anyone who does not practice public hygiene.” Then, I surprised him by saying, “consider it a privilege that you are able to learn how to cope with hardships and suffering. It will prepare you well for the future. Life is hard and a constant struggle. If you learn how to be a tough guy and how to overcome your anxieties and difficulties at a young life, you are more likely to succeed in life than those young people who are coddled and overprotected.” I could instantly see a transformation of his facial expression and energy level. The rest of the session was very positive and productive, focusing on how to benefit from the lockdown.

“For the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth – that Love is the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.” (Frankl, 1985, p. 57)

At the heart of self-transcendence is love for others. This above quote from Frankl is quite powerful. Frankl was able to discover the secret code to resilience and happiness because of his suffering in Nazi death camps.

Yes, love is the only way to our salvation. This is no poetic hyperbole, no romantic sentimentalism, and definitely no overused cliché.

It sounds so simple, but it is so profound that it will take time to understand and practice . It will take the new science of self-transcendence decades of research will reveal the full extent of the power and mechanisms of sacrificial love, which also happens to be the greatest commandments from Jesus (see the bible, Matthew 22:36-40).

We have only scratched the surface with the recent publication of Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization by Scott Barry Kaufman (2020) and my own research of self-transcendence (Wong, 2016b, 2016c). We still know very little of why and how self-transcendence is the key to resilience and happiness.

I can only speculate that we were wired for self-transcendence, that is why have the primary motivation and deepest yearning for self-transcendent love. But sufficient to say that all the research so far has demonstrated that belief in self-transcendence can get your through all the challenging life situations, from aging and cancer, to palliative care. (For more details, please read Wong, 2016d).

Love is always reorienting our attention from self-interest to caring for the beloved. For anyone who has been fallen in love would understand that they would be willing to make any sacrifice in order to bring happiness to the beloved. They would be willing to suffer and endure anything for the beloved’s sake – love gives them courage and resilience. They will suffer joyfully if their sacrifice brings the beloved happiness – love gives them deep satisfaction in spite of suffering. They would be willing to help all those who are related to the beloved – love makes them a caring person.

By the same token, to discover one’s passion for a calling or a career means one is willing to make any sacrifice in order to realize their dream. One would be willing to suffer and endure anything for one’s mission. This passion would give one courage and resilience to self-actualize.

The above are just simple examples. Self-transcendence can permeate and transform every aspect of our life. In short, self-transcendence will transform our inner landscape and empower us to use our body as an instrument for a higher purpose beyond ourselves.

According to PP 2.0, suffering has always constituted an important part of human existence. The average person is primarily concerned about bread and butter issues, but in times like this pandemic, we are thrown into unchartered territory, where we are confronted daily with existential issues, such as suffering and death.

In a paradoxical way, I have shown that how we resolve our existential crisis can have a direct impact on our wellbeing and happiness.

According to a Buddhist Proverb, “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.” But what is psychic pain? How can differentiate it from suffering? What are the differences between inevitable and optional suffering? What are the neuro-mechanisms for happiness in suffering for what or who one loves passionately? That is why I have set up the Research Institute on Flourishing and Suffering (RIFS), the research arm of the International Network on Personal Meaning (See INPM, 2020).

I have also written the book Made for Resilience and Happiness (Wong, 2020b) which provides a road map on how to become stronger and happiness by going thorough the turbulent journey of fighting against the pandemic. At times, the waves may seem too gigantic to overcome, but we have the innate human capacity to achieve something positive in the worst of circumstances though self-transcendence.

For example, for clients who are reluctant to work because of all the risks, difficulties, and the hopelessness at the workplace (such as palliative care or long-term care homes), I would suggest that they challenge themselves with the following tough questions:

1) Confront yourself by asking such simple questions as: Are you a coward who is too afraid of risks? Are you being selfish for not willing to help others? Do you realize how important and valuable your work is? Do you realize that the value or meaning of work does not depend on your position, but on your attitude? Why can’t you bring a positive attitude and give it your best when you go to work?

2) Stop complaining about your work and start thinking what a wonderful experience it is. Yes, it is tough and nerve-wrecking. It is exhausting and frustrating. But also think about what a privilege it is to help others. Do you not realize how many people depend on your work? Do you not feel a sense of significance and dignity to be able to contribute in such a difficult time? Do you feel a sense of pride when so many people are grateful for your heroic work and want to show their appreciation? How many people have the opportunity to be under the spotlight as a hero?

3) Do you realize that love is the most powerful force on earth? Do you know that love can give you the strength to endure anything, the courage to face any danger, and the joy to sacrifice for others? Remind yourself that you work because of your passion for your work, and your passion to help others. More importantly, your work provides the financial support for your loved ones.

4) Say to yourself that you are no longer afraid of suffering and death because love make it worthwhile. The idea of being motivated by sacrificial love will fill your heart with joy and ignite the fire in your belly to play an important role in combatting the deadly monster. Say to yourself that the worse will be over and your life will be stronger and better because you dare to face the crisis, face your own shadow, and found your way back through self-transcendence, the source of positive energy and divine joy deep in your soul.

The Importance of Frankl’s 3-Second Rule

Based on all my reading of Frankl’s writings, the following popular quote typically attributed to Frankl can be best understood as a 3-second pause that can save us from acting impulsively based on our instincts, old habits, biases or emotional reaction without going through our forebrain:

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” (Quote attributed to Viktor E. Frankl.)

These 3 seconds will create enough space for us to make the right decision, which may mean a different outcome, a different destiny:

The 1st second. What is happening in this situation (Mindfulness)? We need to observe what is unfolding with mindfulness or self-detachment in Frankl’s terminology. This brief intentional pause can make all the difference because it enables us to suspend our impulse, bias, or emotional reaction in a split second to allow for more accurate stress appraisal (Peacock & Wong, 1990). Don’t panic even when you feel overwhelmed by all the dark forces attacking you. One moment of stillness can save your life and turn the tide in your favor. One moment of pause will give you the necessary time to seek guidance from your soul and/or from higher power for the right response.

The 2nd second. What are my options or what kind of freedom do I have in this situation (Reflection on freedom)? Whatever the circumstances, we always have some degree of freedom or control; even in the worst-case scenario of having a gun pointed at our head to obey an evil order, we still have the freedom of attitude to take a stance. It is always possible to maintain the freedom to protect our inherent human dignity and core value by boldly declaring: “You can destroy my body, but you cannot kill my soul.” We have the freedom to choose to die happily as a martyr, whereby we instantly transform the human tragedy into a heroic triumph.

The 3rd second. What is the right thing to do? How can I decide which is congruent with my life purpose and core value (Frankl, 1988)? We are constantly confronted with the existential dilemma of choosing between expediency and meaning. Choosing to gain some practical advantage, we may have to sacrifice our integrity or sell our soul, but choosing to do the right thing, we may have to face persecution and suffering.

This third question represents Frankl’s greatest discovery: The question of the meaning of life is not about me or what I can get from life, but about the human family or what life demands of me in terms of moral obligation. This question is actually a wake-up call, which may result in an “aha!” moment of awakening and a quantum shift from “What is in this for me?” to “What can I offer to others?”

Sadly, most people are content with living in a two-dimensional space; to them, life is all about eating, drinking, and personally being happy. They will only work if they have to make a living. However, some serious reflection on the third question may open our eyes to the vertical spiritual dimension of life, enabling us to live at a deeper level.

The first and second questions of the 3-second rule require the important mechanism of self-detachment, whereas the third question requires self-transcendence (Wong, 2016c).

The 3-second rule serves the same purpose as the Chinese idiom of “Think thrice before you act” (三思而行), except that it is more explicit in providing a clear guide about how to think thrice. The end result is that it reduces the likelihood of making the wrong decision.

Together, these two spiritual mechanisms–mindfulness (self-detachment) and meaning (self-transcendence)–function like a pair of strong wings that can lift you above your stress and personal problems into a new realm of hope and possibilities. Most mental health professionals who mentioned Frankl did not realize that these two mechanisms are the double-helixes for our meaningful life just as the double-helix DNA is essential for our biological life.

Together, these two spiritual mechanisms represent a fundamental re-orientation from everyday self-interested obsessions, towards a broader concern for others (e.g., Adler, 1938/2011) or something greater than oneself (e.g., Frankl’s [1985] idea of ultimate meaning). Therefore, meaning may be unique in each individual and in each situation, but the fundamental structure of meaning is the same, always shifting from self-preoccupation to a larger story, even a meta-narrative. Our heart needs to be large enough to embrace others, nature, and the Creator in order to achieve self-transcendence and self-actualization.

These 3 seconds may even buy you enough time to laugh at the absurdity of life and make yourself happy: “Humour…can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds.” (Frankl, 1985, p. 63)

In sum, meaning lies in going beyond the bondage of carnal desires or egotism (e.g., No Self according to Buddhism, or self-crucifixion according to Christianity) so that you may be free to connect with others, with nature, or with transcendental reality and higher values in an authentic and generous way.

Once you have made the quantum shift to the vertical dimension of human existence–the spiritual dimension–you are in a position to decide how to realize meaning and value in your life regardless of circumstances. To further help you to make the right decision, Frankl has also identified three fundamental values, as discussed below.

Frankl’s Three Avenues of Value

“Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.” (Frankl, 1985, p. 57)

Meaning is related to value. Not every goal has objective value. Subjective meaning needs to be related to some normative value. It is amazing how Frankl was able to summarize the complex issues regarding the relationship between meaning and values in a simple and comprehensive way. One’s subjective meaning needs to be congruent with the following enduring values in order to be truly beneficial and worthwhile:

Creative Value. What you can give to the world through your unique creative work. Whenever you have the freedom and opportunity to do something worthwhile and creative with your time or your life, you would want to do it whole-heartedly, so that it bears your unique imprint of personality, character strengths, experience, and imagination. You can create something valuable and leave a footprint that helps others. It does not make any difference whether it is a paid job, volunteer work, or a hobby; it is not the nature of work but the nature of your attitude towards you work that makes it meaningful or significant. Whether your work has enduring value all depends on whether you care for it enough to create some real value. When your work matters to you, it will in turn makes your life matter or significant because of your unique contribution.

Experiential Value. How you can receive it from the world through your appreciation. You can savour the moment through your five senses. You can also discover some hidden beauty and goodness in people, nature, or negative events with mindfulness and a meaning mindset (Wong, 2011). The secret to meaning and happiness is that you can always discover something beautiful in life, no matter how brutal life is. You can discover it with an attitude of humility, appreciation, imagination, and faith in the transcendental reality–all involving the activation of your right brain. Suffering can be painful but appreciate the precious life lessons from going through it. The most important part of this value is the appreciation of a love relationship, which is a like a stream in a desert or a ray of sunshine after a dark night. True love always involves the pain of yearning during separation and grieving during death, but it is always a major source of meaning capable of transforming people’s lives for those who accept the sacrifice demanded by love.

Attitudinal Value. How you can experience it through the “defiant power of the human spirit”. It can be an attitude of courage or an affirmation of faith to protect your human dignity and core values, even when you were stripped of everything. It is an attitude that enables you to face imminent death with your head held high and your eyes turned towards Heaven. It will give you the mental and emotional toughness to survive COVID-19.

Wong’s Definition of Meaning

Meaning therapy is actually depth therapy; it is about sinking down deep roots so that we can survive the violent storms of life. To use a war metaphor, when we are bombarded by enemy fire and surrounded by toxic gas or pathogens with nowhere to go, we can always go deeper and deeper until we reach the innermost recess of our soul, the spiritual and healthy core which cannot be corrupted, according to Frankl’s logotherapy.

Another way to clarify whether one’s desired value is really worthwhile or meaningful is Wong’s (2010) PURE test. Not all goals are equal–some are trivial pursuits, and some are misguided self-destructive ambitions. To avoid self-deception, one can always apply the following four criteria:

- A meaningful life is purposeful. We all have the desire to be great or significant, we all want our life to matter, to be somebody rather than a nobody. We all want to make a difference in the world. A sense of mattering or significance imbues our lives with meaning. The intrinsic motivation of striving to improve ourselves to achieve a worth goal is a source of meaning. That is why purpose is the cornerstone for a meaningful life. Even if you want to live an ordinary life, you may still want to do the best you can so that you will be known as a good neighbor, a decent human being. But not all purposes are alike. If our life purpose is centered around getting rich and famous by any means, even if it involves stepping on others, then such a life goal is neither responsible nor rationally justifiable.

- A meaningful life is understandable or coherent. We need to know the reasons for our existence, or the reason or objective of our actions and plans (Antonovsky, 1987). Having a cognitive understanding or a sense of coherence is equally important for meaning.

- A meaningful life is a responsible one. We must assume full responsibility for our life or for choosing our life goal. Self-determination is based on the responsible use of our freedom. This involves the volition aspect of personality. The next criteria will explain why responsivity = meaning.

- A meaningful life is enjoyable and fulfilling. It is the deep satisfaction that comes from having made some difference in the world. This is a natural by-product of living a life of significance and the self-evaluation that “my life matters”.

Together, these four criteria constitute the PURE definition of meaning in life. Most meaning researchers support a tripartite definition of meaning in life: comprehension, purpose, and mattering (George & Park, 2016; Martela & Steger, 2016), but these elements are predicated on the assumption that individuals assume the responsibility to choose the narrow path of meaning rather than the broad way of hedonic happiness. In the existential literature, freedom and responsibility are essential values for an authentic and meaningful life (In addition to Frankl, you can also read Rollo May, Irvin D. Yalom, Emmy van Deuzen, etc).

For instance, my life is meaningful because I chose the life goal of reducing suffering, as well as bringing meaning and hope to suffering people. This was not an easy choice, but it was the only choice if I wanted to be true to my nature and my calling. I had to be what I was meant to be.

Faith is the Key to Understanding Frankl’s Cure

“The prisoner who had lost faith in the future – his future – was doomed. With his loss of belief in the future he also lost his spiritual hold; he let himself decline and become subject to mental and physical decay.” (Frankl, 1985, p. 95)

According to Frankl, logotherapy is spiritual therapy. Just as cognitive psychology restored the mind to psychology after behaviourism, Frankl restored the soul and spirituality to mainstream psychology, which was dominated by reductionist and determinist materialism. The soul represents the most sacred spot in everyone’s life; it is where we discover our best angels. It is where we encounter what is sacred and transcendental. Most importantly, it is where we find our passion for life.

The key to understanding the power of Frankl’s meaning therapy is to discover the power of faith, such as faith in a better future, in the self, in others, and in God. Faith in God is very involved in the exercise of attitudinal value. All hope is based on faith, especially hope in hopeless situations.

What kept Frankl alive through multiple Nazi death camps was precisely his faith in a future reunion with his wife (not knowing that she was already dead), faith in the enthusiastic acceptance of logotherapy in the world, and faith in the inherent value and sanctity of life. He never gave up the belief and hope that allied forces would arrive, and he would still be alive to fulfill his dreams.

Faith, nothing but faith, can counteract the horrors of life and death. All our pursuits of meaningful work and meaningful relationships are initiated by faith and sustained by faith even when we are living in a hellhole. We need faith to sustain our hope in an uncertain future which is beyond our control.

It does not matter whether you have faith in God, Jesus, Buddha, or the spirit of our ancestors. If you have faith in someone or something greater than yourself, you would have a better chance of overcoming seemingly insurmountable problems and defeating more powerful enemies.

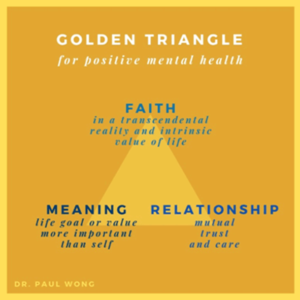

In sum, wellbeing can be conceptualized in terms of a golden triangle as illustrated in figure 1. Each of the three components of this triad is possible because of the of double helix of self-detachment (mindfulness) and self-transcendence (meaning) that liberate us from self-absorption.

Just as social distancing saves lives from the coronavirus, self-distancing and self-transcendence can provide the necessary life space that saves us from the heart of darkness, characterized by greed, pride, ignorance, and egotistic pursuits. Faith, meaning, and love are like air, food, and water which are essential to our physical health.

Figure 1

The Golden Triangle

Note. This figure was posted on the author’s social media network.

In Frankl’s view, life is priceless. One cannot put a price tag on anyone’s life because we were all created equal in the image of God and endowed with greater value than any material things. That’s why he encourages people to say Yes to life, no matter what. Value has intrinsic value because of its singularity and capacity to grow and to make a unique contribution. What makes a fragile life resilient is the primary motivation to discover and serve something worth dying for; the capacity of self-transcendence makes suffering not only bearable, but as a source of deep joy.

A related argument in favor of life is that a living individual is always able to create some value or wealth, whereas a dead individual will be an emotionally terrible loss to their loved ones and entails economic loss. Therefore, whether from the perspective of cost/benefit analysis or from the framework of humanistic values, saving lives should be given a higher priority over saving the economy. In short, life always trumps money.

We can ask our clients to reflect and ask themselves the following self-reflection questions:

1) What do I want to do with my one and only life?

2) What is worth all my effort and sacrifices?

3) What is life, if there is no dream, no suffering, no overcoming, and no hope?

Reflecting on these three questions may set one free from one’s shallow meaningless existence and get one started on a risky but exciting adventure.

We should also encourage our clients to meditate on the following three self-affirmations:

1) I believe that life has meaning till I breaths my last my last.

2) I am grateful that the reality of suffering and death shows me what I was meant to be.

3) I am confident that I can find my way to a happy and meaningful life even in a hostile environment.

As Frankl (1946/2020) once said regarding the inherent, unconditional value and meaning of individual life:

“What remained was the individual person, the human being — and nothing else. Everything had fallen away from him during those years: money, power, fame; nothing was certain for him anymore: not life, not health, not happiness; all had been called into question for him: vanity, ambition, relationships. Everything was reduced to bare existence. Burnt through with pain, everything that was not essential was melted down — the human being reduced to what he was in the last analysis: either a member of the masses, therefore no one real, so really no one — the anonymous one, a nameless thing (!), that ‘he’ had now become, just a prisoner number; or else he melted right down to his essential self.”

PP 2.0 and Meaning-Focused Therapy

While Martin Seligman’s positive psychology is about happiness and flourishing, Wong’s PP 2.0 (Wong, 2019) is about suffering as the gateway to flourishing. Wong’s two approaches represent the Yin and Yang halves of the wellbeing circle.

COVID-19 has shown that the basic tenets of PP 2.0 are undeniable aspects of the human condition: (1) we all live in a dangerous world full of evil and suffering; (2) all human being have inherent limitations and vulnerability; and (3) flourishing is impossible without overcoming the frailty and the dark side of life (Fowers et al., 2017; Wong, 2020c).

In contrast to the dominant message of American positive psychology that emphasizes what is good and right in life, the message of PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011, 2016b) and meaning therapy is that life is full of suffering and injustice. We need to give up our unrealistic expectations of only good things and confront life with a sense of tragic optimism and struggle for a better future with courage. Paradoxically, more recent research has shown that such a realistic life orientation actually increases our capacity for resilience and happiness.

Contrary to the popular belief that we should avoid painful emotions, all our efforts to protect ourselves against suffering actually make us more vulnerable to life’s problems and mental illness. Running away from what we fear only make it scarier. Paradoxically, according to Frankl’s strategy of paradoxical intervention, to confront and exaggerate our worst fear to the point of being laughable actually reduces our fear. That is why I advocate the radical acceptance of personal responsibility to face suffering with courage.

Consequently, the most important tenet of PP 2.0 is that sustainable flourishing can only be achieved only on the foundation of overcoming suffering – a bold claim that has already received considerable empirical support. I have devoted two decades integrating Frankl’s ideas with positive psychology research (e.g., Wong, 2007a, 2016c).

The main thrust of my recent book Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 is that we are wired in such a way that our genes and brain have the necessary capacities to survive and thrive in any adverse situations, provided that we are awakened to our spiritual nature and cultivate our psychological resources, such as faith, love, and meaningful work. In the (2015) book The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It, McGonigal highlights new research indicating that stress can, in fact, make us stronger, smarter, and happier, if we learn how to cultivate the power of beliefs and embrace stress as source of energy.

We have a serious mental health crisis because we are like the fish out of water, living in a materialistic consumer society and a digital world without paying much attention to our spiritual needs. Technological progress contributes to our physical wellbeing, but it also destroys the soul if we do not make an intentional effort to care for our soul.

Meaning Therapy helps people get back into water—to meet people’s basic psychological needs for loving relationships, meaningful work, faith in God, and some transcendental values. In times of life crisis, collective madness, and an uncertain future, we need to get back to the basics of:

- Faith in God or spiritual core values

- Love for people and develop relationships

- Meaning in one’s work and pursuits.

This positive triad, as depicted by the golden triangle, has enabled humanity to survive since the beginning of time; it is still essential in overcoming depression, addiction, and suffering, and creating a better future.

Paradoxically, meaning therapy teaches the basics of positive mental health—radical acceptance of suffering with courage; a return to the core values of faith, love, and meaning; and the life intelligence of coping with the adversities and vicissitude of life.

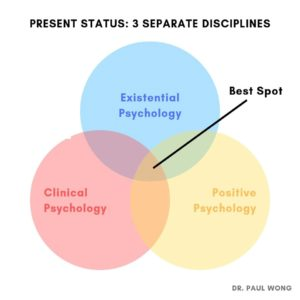

My integrative meaning therapy is innovative in many ways. The most important departure from traditional practices of psychology is that meaning therapy advocates a pluralistic and integrative approach. It is opposed to the prevailing tribal or silo mentality; it believes that the more we collaborate and work together, the faster we can resolve the mental health crisis.

Figure 2 represents the current situation. There is only limited cooperation and overlaps in the three disciplines. One may substitute existential psychology with religion, or replace clinical psychology with psychiatry, but the situation remains the same – they all operate as separate disciplines.

Figure 2

The current status of three psychology disciplines

Note. This figure was posted on the author’s social media network.

I propose the best spot for effective psychotherapy is the small common core, where the therapist is able to address a client’s existential crisis, psychological disorders, and basic need for happiness and meaning in the same clinical session.

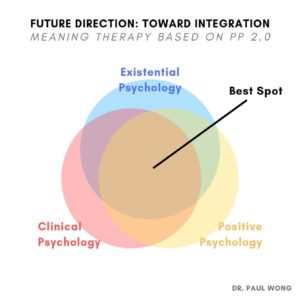

In contrast to the current practice, I have attempted to increase the common core as shown in figure 3. There are at least three reasons for this movement towards integration:

- Clinical psychology or psychiatry and positive psychology are inadequate in and by themselves; they really need each other to be complete. It is like the synthesis that emerges from both the thesis and antithesis, as I have argued for PP 2.0.

- Existential psychology has to do with the condition of human existence, relevant to all people. Therefore, it is impossible for any psychotherapist to totally ignore the client’s existential concerns. I have argued that all psychotherapists need to have existential competency.

- The existential givens include both the basic primitive emotions of shame, guilt, and fear, and the basic emotional needs for faith in something stronger than oneself, relational support, and meaning (both symbolic meaning and objective values for the human community to survive).

Figure 3

Future integration of three psychological disciplines

Note. This figure was posted on the author’s social media network.

During this unprecedented time, in the presence of a contagious pandemic, a high level of anxiety is a natural emotional reaction. Therefore, generally, the problems come from a case of living through a difficult time. However, in some serious cases of mental disorder, psychiatric morbidity and physical illness needs to be ruled out prior to meaning therapy. Frankl (1985) considered logotherapy as a medical ministry or an adjunct therapy to deal with existential suffering. Likewise, my proposed integrative meaning therapy can so be regarded in the same way.

One of my visions is to harness the power of AI and technology to help people to meet their deepest needs for meaningful relationship, meaningful work, and meaningful spiritual experience. I believe that when people are satisfied in these three life domains, they will enjoy good mental health and wellbeing. For example, regarding relationships, we can make use of brain-computer interactions and develop all kinds of computer-assisted devices and apps that allow people to assess another person’s character trait, relational skills, and capacity for compassion or empathy. In the area of work, we can also develop AI-powered coaches to teach people to discover their skills, interests, and aptitude, and to explore the different areas of work or to create their own career path. Therefore, the 4IR can also help promote the new approach in mental health and help people find meaningful relationships and work.

References

- Adler, A. (1938/2011). Social interest: a challenge to mankind. Martino fine books.

- Akhtar, S. (2014). Sources of Suffering: Fear, Greed, Guilt, Deception, Betrayal, and Revenge. Routledge.

- Allport, G. W. (1981). Personality and Social Encounter: Selected Essays. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Anderson, J. & Rainie, L. (2018). 3. Concerns about the future of people’s well-being. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/04/17/concerns-about-the-future-of-peoples-well-being

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). The Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series and the Jossey-Bass health series. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass.

- Bastian, B. (2018). The other side of happiness: Embracing a more fearless approach to living. New York, NY: Penguin.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Benning, T. B. (2016). No such thing as mental illness? Critical reflections on the major ideas and legacy of Thomas Szasz. BJPsychBull, 40(6), 292-295. Doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.115.053249

- Camus, A. (1947/2020). The Plague (S. Gilbert, Trans.). Mercy House.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Deacon, B. J. (2013). The Biomedical Model of Mental Disorder: A Critical Analysis of Its Validity, Utility, and Effects on Psychotherapy Research. Clin Psychol Rev, 33(7), 846-61. Doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2020). COVID-19 situation update worldwide, as of 18 August 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases

- Fowers, B. J., Richardson, F. C., & Slife, B. D. (2017). Frailty, suffering, and vice: Flourishing in the face of human limitations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Frankl, V. E. (1946/2020). Yes to life in spite of everything. Penguin Books.

- Frankl, V. E. (1977/2011). The Unheard Cry for Meaning.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1988). The Will To Meaning. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

- Friedman, T. L. (2016). Thank You for Being Late: An Optimist’s Guide to Thriving in the Age of Accelerations. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Galer, S. (2020). Intelligent Robotic Process Automation Is Not Your Average Top 2020 Trend. https://www.forbes.com/sites/sap/2020/02/06/intelligent-robotic-process-automation-is-not-your-average-top-2020-trend/#3e86ed561cc9

- George, L. & Park, C. L. (2016). Meaning in Life as Comprehension, Purpose, and Mattering: Toward Integration and New Research Questions. Review of General Psychology, 20(3). DOI: 10.1037/gpr0000077

- Gloag, O. (2020). Albert Camus: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Huda, A. S. (2019). The Medical Model in Mental Health: An Explanation and Evaluation. Oxford University Press.

- (2020). Research institute on flourishing and suffering (RIFS). Meaning.ca. https://www.meaning.ca/meaning-centred-interventions/research-institute-on-flourishing-and-suffering/

- Institute of Medicine, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Committee on Pathophysiology and Prevention of Adolescent and Adult Suicide, Goldsmith, S. K., Pellmar, T. C., Kleinman, A. M. & Bunney, W. E. (Eds.). (2002). Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. The National Academies Press.

- Jyoti, R., & Schubmehl, D. (2019). IDC FutureScape Webcast: Worldwide Artificial Intelligence 2020 Predictions. https://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=WC20191118

- Kaufman, S. B. (2020). Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization. TarcherPerigee.

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

- McDonald, M. J., Wong, P. T. P., & Gingras, D. T. (2012).Meaning-in-life measures and development of a brief version of the Personal Meaning Profile. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 357-382). New York, NY: Routledge.

- McGonigal, K. (2015). The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It.

- O’Donnell, J. (2020, June 21). As suicide, addiction death projections soar amid COVID-19, treatment centers struggle to stay alive too. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2020/06/21/covid-spurs-mental-health-needs-treatment-centers-go-underfunded/3191251001/

- Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1990). The Stress Appraisal Measure (SAM): A multidimensional approach to cognitive appraisal. Stress Medicine, 6(3), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2460060308

- Peck, M. S. (1978/2012). The Road Less Travelled. London: Rider.

- Peterson, J. B. (2018). 12 Rules for Life: An antidote to chaos. Toronto, ON: Vintage Canada.

- Purtill, J. (2020). People no longer believe working hard will lead to better life, survey shows. net. https://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/2020-edelman-trust-barometer-shows-growing-sense-of-inequality/11883788?fbclid=IwAR0k9AGBXutKULaFIYMrwKc52-yxqQqe0302hQAbpv62q8auYFPVthrc9Uc

- Pytell, T. (2020). Viktor Frankl’s Search for Meaning: An Emblematic 20th-Century Life. Berghahn Books

- Roy, L. (2020). Collision of crises: how COVID-19 will propel drug overdose from bad to worse. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lipiroy/2020/05/23/collision-of-crises-how-covid-19-will-propel-drug-overdose-from-bad-to-worse/#cf6f9067d3ab

- Samoon, A. (2020). Technological change and mental health: How will the workforce of the future cope with the fourth industrial revolution? com https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2020/06/technological-change-and-mental-health-how-will-the-workforce-of-the-future-cope-with-the-fourth-industrial-revolution.html

- Schwab K. (2018). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Fourth-Industrial-Revolution-2119734

- Swart, M. (2020, March 12). How the coronavirus has deepened human rights abuses in China. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/cloneofcloneofcoronavirus-deepened-human-right-200312074518781.html

- Szasz, T. S. (1961). The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct. Harper & Row.

- Takano, Y. & Wong, P. T. P. (in press). Deterritorialization of Shame in Japan During the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). In C. H. Mayer., E. Vanderheiden, & P. T. P. Wong (Eds.), The meaning of shame revisited in cultures of the 4th Industrial Revolution.

- Twenge, J. M. (2017). iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy–and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood–and What That Means for the Rest of Us. Atria Books.

- Vinayak, V. (2019, September 6). The human rights implications of China’s social credit system. Oxford Human Rights Hub. https://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/the-human-rights-implications-of-chinas-social-credit system/#:~:text=China’s%20social%20credit%20system%20is,commensurate%20commitment%20to%20human%20rights.&text=This%20system%20surveils%20every%20online,’desirability’%20of%20these%20actions

- Wan, W. (2020, May 4). The coronavirus pandemic is pushing America into a mental health crisis. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/05/04/mental-health-coronavirus/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2007). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Anthology of Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen Inc.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2010). What is Existential Positive Psychology? International Journal of Existential Psychology & Psychotherapy, 3(1), 1-10. http://www.drpaulwong.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/what-is-existential-positive-psychology.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Existential positive psychology. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/179/158 (The second edition of the Encyclopedia of positive psychology was not published because of Lopez’s death, therefore, it was eventually published in my journal [IJEPP])

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1).

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016c). Meaning-seeking, self-transcendence, and well-being. In A. Batthyany (Ed.), Logotherapy and existential analysis: Proceedings of the Viktor Frankl Institute (Vol. 1; pp. 311–322). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016d). Self-transcendence as the path to virtue, happiness and meaning. Paper presented at the research working group meeting for Virtue, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life Project, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. https://virtue.uchicago.edu/page/paul-t-p-wong-june-2016-working-group-meeting-topic (Funded by the John Templeton Foundation)

- Wong, P. T. P. (2017). Logotherapy. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of abnormal and clinical psychology (pp. 1984). New York, NY: Sage.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly [Special Issue].Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020a). Meaning and evil and a two-factor model of search for meaning [Review of the essay Meaning and Evolution, by R. Baumeister & W. von Hippel]. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 4(1), 63-67. DOI: 10.26613/esic/4.1.170

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 According to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. Toronto, Canada, INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020c). The maturing of positive psychology and the emerging PP 2.0 [Book review of Positive Psychology (3rd ed.) by William Compton and Edward Hoffman]. International Journal on WellBeing, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i1.885

- Yong, E. (2020). How the Pandemic will End. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/03/how-will-coronavirus-end/608719

- Yuval N. H. (2018). Homo Deus: a Brief History of Tomorrow. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2020). Existential Positive Psychology and Integrative Meaning Therapy. International Review of Psychiatry. DOI: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.