Dr. Paul T. P. Wong’s autobiography, A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith, is published in weekly installments. Stay updated here.

On one afternoon several years ago, when I was alone in my home study thinking about my brother David’s life, I was suddenly overcome with tidal waves of sad emotions until I broke down crying. For the first time in my life, I cried loudly and uncontrollably, with my whole body shaking as if a dam had broken and all my pent-up emotions of pain burst out with irresistible force. I came very close to screaming from the depth of my being.

I cannot fully understand this strong emotional outburst. Maybe I was mourning more than the tragic loss of a very promising life. Maybe I was crying for a whole generation of Chinese intellectuals who dedicated their lives to serving their country, only to be betrayed by their government. Maybe I was crying for all the victims of persecution in China down through history, whose blood could turn the Yangtze River red.

Yesterday, as I was listening to my son Wesley speak about his research at Harvard, I could not help but wonder about David. He could have had an equally rewarding research career at MIT had he not made the wrong choice of returning to China. As David’s life played back before my mind’s eye as a tragic epic, I tried very hard to make sense of all the terrible things that happened to him.

- How could a brilliant Caltech Ph.D. die alone as a pauper in low-income housing for retired homeless soldiers?

- How could an innocent researcher be framed and defamed, resulting in a ruined reputation and ostracization?

- Who was responsible for all his misfortunes?

- Is there justice in this world? Is vindication possible?

- Is there any room for someone who believes, like Fan Zhongyan (范仲淹), “I’d rather die for speaking out than live and keep my silence” (寧嗚而死,不默而生)?

I have no answer for these troubling questions, but I still believe that he has not lived in vain. At least, he has taught me the importance of grit and played a vital role in shaping me to be the kind of person I am.

An Inspiring Big Brother

David and I were six years apart, yet we were very close as brothers. When I was only eight or nine years old, he taught me and Constant (my younger brother) how to dive head first from the highest diving board, about 16 feet above the pool. We had just learned how to swim, but he challenged us to dive in order to learn how to overcome fear.

I was the first one to climb up to the diving tower. Looking down from the tall platform, I was terrified. “Don’t be afraid; just jump!” he shouted from below. I did it. I still remember the impact of hitting the water, the unpleasant pressure on my eardrums, and the subsequent calm of being in the deep end of the pool. Afterward, I felt very good for having had the courage to do something daring.

When we were in Hong Kong, David often took us swimming, hiking, or boating on the weekends. He would take a rowboat to the sea and challenge us to dive to the bottom to retrieve something. He called that endurance training. He wanted us to grow up and become daring and tough guys like him. He maintained this tough guy image to the very end.

Strange as it may sound, even before we reached puberty, he taught us to take cold showers as a way to control sexual desire and prevent masturbation. In some ways, he was a surrogate father as our father never had the time to teach us the lessons of life. Dave might have come across as rude and offensive to some people, but to us, he was as loving and caring as an older brother could be.

His love for nature and adventure really inspired me. When he left us for UCLA, I continued to pursue this interest but elevated it to a higher level. One day, I and Constant took a rowboat to sea and tried to reach a distant island, even though the weather station had already issued a warning that a storm was coming and there were no other boats at sea. Eventually, a motor boat had to come to our rescue and tow us to shore.

On another occasion, I challenged Constant to walk with me all day to the New Territories through the valleys and mountains rather than on the paved highway. We only carried with us a bottle of water and some dry food. This was intended to be an endurance test to toughen us up. By the time we took the bus home, we had sustained all kinds of scratches on our arms and legs because of the thickets we had to fight through. Right after this survival test, Constant was sick with a high fever for a few days.

Dave also exposed us to his love for music. He taught us how to play the harmonica. His favorite songs were “Merry Widow,” “A Beautiful Dreamer,” and “You Are My Sunshine.” Some evenings, we played these songs together and had a blast!

One year, when I was about ten, he coaxed me and Constant to give him all our lucky money received during the Chinese New Year celebration. He said he wanted to use the money to buy records of classical music so that we could all enjoy it together. He bought mostly Beethoven’s symphonies. At first, it felt very weird when he closed the living room door and turned off the lights so that we could focus on the music, but this was the way that he taught us to appreciate the grandeur and power of Beethoven.

I still remember how I was awe-struck by the four-note opening motif of the 5th Symphony; I felt as if I was hit by a thunderbolt. “This is the Fate Symphony,” David said during his brief introduction. “It was composed during the time when he was losing his hearing.” The message I got from listening to this symphony was that when fate knocks at the door, we better pay immediate attention and get prepared for the inevitable storm. These four opening notes stirred me deeply even in my childhood dreams.

The choral finale of the 9th Symphony Ode to Joy also had a strong impact on me. It opened my eyes to the wonder of divine love under a starry sky. A tingling sensation went through my spine as I immersed myself in the voices-only chorus.

I wonder whether David’s love of music and its heroic motifs helped lift up his spirit during those dark and painful days later in his life. His defiant human spirit stayed with him until his last breath.

Brilliant Early Years

Good times do not distribute evenly. For David, most of the good things happened in his first half of life. For me, it was just the opposite.

His talents in science were evident even in high school. He achieved almost 100% in his science and math courses. He even had his own lab, equipped with a microscope and chemicals. He was well known by his science teacher for producing high-quality slides with all kinds of specimens (I overheard this from my father).

However, he faced expulsion from his high school because of being active in political protests and demonstrations against the Kuomintang Government. Father had to plead with the school principal not to expel him on grounds of his outstanding academic record. Father promised the principal that he would prevent him from taking part in any further demonstrations.

During his last year in high school, he was accepted by both Tsing Hua University (清華大學) and Yen Ching University—known as China’s Harvard and Yale—even though he was running a high fever when he went to Peking to write the grueling entrance exams.

A year later, he transferred from Tsing Hua Medical School to the Science Program at UCLA and graduated with First-Class Honors and won a Golden Key. He then studied with Verna Shoemaker and Linus Pauling (a Nobel Laureate) at the nationally top-ranked Californian Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he received a Ph.D. in Physical Chemistry in 1957. His area of research had to do with the physical and chemical properties of the structure of crystals.

Soon after his graduation from Caltech, he received a job offer from MIT but then decided to return to China with a small group of distinguished Chinese Scientists in America, such as Yang Chen-Ning (楊振寧) and Lee Tsung-Dao, both of whom shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957.

In spite of his patriotic ideal to contribute to China’s scientific development, he was not allowed to do any research. Instead, he was exiled to the countryside for “thought reform” because of his outspokenness. Disillusioned, he wanted to get out of China. Finally, armed with a special letter of permission from the then-Premiere of China Chou En-Lai, he was able to leave for Hong Kong to visit his sick father. Shortly after his arrival in Hong Kong, he was invited to visit Taiwan and welcomed as a hero. This visit was widely reported in Taiwan and even mentioned in Time Magazine.

He started teaching at the National Tsing Hua University and was later named the Distinguished National Science Foundation Professor at Tsing Hua. One of his most famous graduate students was Lee Yuan-Tseh, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1986. They had several scientific publications together.

He started teaching at the National Tsing Hua University and was later named the Distinguished National Science Foundation Professor at Tsing Hua. One of his most famous graduate students was Lee Yuan-Tseh, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1986. They had several scientific publications together.

During his courtship of Shui Lu (徐露), the most celebrated star in Peking opera in Taiwan during the 60s and 70s, he would purchase all the tickets of the first few rows at her performances so that he could sit there alone in order to get her attention.

When they got married, this event was touted by mass media as a wedding between a hero and a beauty. Their wedding was attended by many of the celebrities and elites in Taiwan.

Socially and academically, he was on top of the world. However, he was totally unaware that his larger-than-life persona and his academic success were actually seeds of self-destruction—an important lesson in my theorizing about second wave positive psychology (PP2.0) years later (Wong, 2011).

His Futile Struggle for Justice

In any Western country, given David’s academic credentials and research achievements, his career trajectory should have been pretty good. Thus, it is simply unthinkable that his routine grant application to the National Science Council in Taiwan should lead to his dismissal from Tsing Hua and his social descent to become a poor outcast. What happened to him was not only an academic scandal but also a testimony against a system where political connections and personal vendettas were allowed to trump well-established due process in grant evaluation.

In order to properly appreciate the gravity of this scandal, readers need to have some basic understanding of the grant application process. All professors in reputable universities need to apply for external grants to support their research. Given the practice of “publish or perish,” professors have to apply for grants in order to fund their research. The worse that can happen to any grant applicant is the rejection of the proposal. Even in this case, the applicant can always revise the proposal and submit it again to the same or different granting agency. To my knowledge, no one ever got fired or ruined for life because of a rejected grant application in North America.

In the United States, the main funding agencies are the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Health. The government provides funding to these agencies, which then distribute the money to various principle investigators (PIs). Let me share my experience at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), a part of the NIH. For five years, I worked at the NIMH in Washington on the Panel of Biological and Behavioral Sciences (1980-1985), which reviews all the applications submitted to our section. The photo shows me and my fellow panelists. Note that all the panelists were well-known researchers, nominated by their peers; not a single member of the panel was a political appointee.

Another important thing about our government-funded granting agency was that the Director only decided on the size of the envelope (i.e., the amount of funding) assigned to each panel, but he never interfered with the adjudication process or the decisions of each panel. When there was no expertise on the panel, we sought out an ad hoc reviewer outside the panel to evaluate a particular grant. In Canada, things work much the same way, as I have served as an ad hoc reviewer for federal and provincial granting agencies for many years.

Another important thing about our government-funded granting agency was that the Director only decided on the size of the envelope (i.e., the amount of funding) assigned to each panel, but he never interfered with the adjudication process or the decisions of each panel. When there was no expertise on the panel, we sought out an ad hoc reviewer outside the panel to evaluate a particular grant. In Canada, things work much the same way, as I have served as an ad hoc reviewer for federal and provincial granting agencies for many years.

Given this background knowledge, what happened to David’s grant application was beyond the pale of granting activities; it more like a case of political scheming in order to destroy the reputation and career of a researcher.

David’s main research interest was structural crystallography and crystal chemistry. His contributions included the development of new techniques for crystallizing proteins using chemical cross-linking and the application of these methods to discover the crystal structure of acid protease in cross-linked form. His research achievements were widely recognized by his peers.

It was like being struck by a thunderbolt on a sunny day. Unexpectedly, David became the center of a political-academic storm in 1979, when Dr. Shu Shian-Siu (徐賢修), then Chair of the National Science Council in Taiwan, engineered David’s dismissal from the National Tsing Hua University by spreading a malicious peer review from the late Dr. Choh Hao Li (李卓皓) to the entire faculty and administration of Tsing Hua. According to David, he had something to do with Dr. Shu being removed from the presidency of Tsing Hua because of corruption. Dr. Li was recruited by Dr. Shu as a “hired knife” to destroy David’s career.

In this case, there were several blatant violations of proper procedures. First, the confidentiality of grant reviews should be protected. It was simply unheard of that Dr. Li’s review should be widely circulated all through Tsing Hua. Second, while Li was well known for his hormone research, he was not an expert in crystallography. There was no reason why the two highly positive ad hoc reviews of David’s proposal by two experts in crystallography were dismissed and suppressed by Dr. Shu. Third, instead of evaluating the scientific merit of David’s research proposal, Li launched a vicious personal attack based on innuendos, hearsays, and unsubstantiated accusations.

David’s scientific career ended prematurely and unceremoniously. Neither tenure nor his research accomplishments could save him from the scheme of powerful political figures. When I read and re-read Dr. Li’s review, I shook my head repeatedly in disgust. I could not understand why an internationally renowned professor would descend to such a low level of character-assassination. Following his dismissal from Tsing Hua, David began a long and costly legal battle against Shu and Li for libel. This prolonged litigation not only reduced him to poverty but also contributed to his divorce.

Eventually, Dr. Shu was removed as Chair of the National Science Council as a result of this legal battle. Dr. Li was disgraced by his infamous peer review. The only personal gain in the costly lawsuit was that he was able to obtain all the documents surrounding this case. It appears that Dr. Li wrote the scandalous review against his better judgment in order to return a favor to Dr. Shu.

The legal fees to defend Dr. Li came from the Taiwanese Government because Dr. Shu was closely connected to President Chiang Ching-Kuo. However, David had to mortgage his house to fund the lawsuit. In the end, the court ruled that since this case was related to the National Science Council in Taiwan, it had to be settled there. It was a moral victory, but David was destroyed financially and professionally. The controversy of David’s legal battle was reported in detail by Perspective Monthly in Hong Kong and major newspapers in 1979 and 1980. A brief summary of this case can be found here.

Twenty years after David’s dismissal, Li Ao (李敖), a well-known writer and political activist in Taiwan intervened. He did a TV interview with David and wrote about this case to seek vindication. This case again received a great deal of public attention but did not achieve the desired result. Still, David never gave up hope of eventual vindication and financial compensation. He devoted 20 years of his life exploring possible legal avenues to seek justice. Later, his obsession evolved into grandiose delusions. He believed that the CIA of the government of the United States would clear his name and that George Bush would intervene on his behalf.

My main motivation to report about this scandal is twofold. First, I want to restore my brother’s reputation and show the dark underbelly of academia in Taiwan during Chiang Ching-Kuo’s presidency. Second, my own research career has also been adversely affected by an unfair peer review system, which I will report in a later chapter. Part of my unfulfilled dream is to fundamentally reform the peer review system so that it can no longer be used as an instrument to advance some people’s academic careers and hinder that of others for selfish reasons.

Miserable Later Years

After his dismissal, David could not find any teaching or research positions in Taiwan. Finally, through an American connection, he was able to teach at a university in the United Arab Emirates for three years. This meant that he had to move to the Arabs alone. This prolonged separation also contributed to his divorce in 1986. Two years after the divorce, Shui Lu was remarried to the director of the Central Intelligence Bureau, Mr. Shen Tze Yuan (沈之岳), but David never married. Mr. Shen is known in Taiwan as the “Father of Intelligence.” When I met him many years later, he was already retired and devoting all his time to Christian ministry.

After his dismissal, David could not find any teaching or research positions in Taiwan. Finally, through an American connection, he was able to teach at a university in the United Arab Emirates for three years. This meant that he had to move to the Arabs alone. This prolonged separation also contributed to his divorce in 1986. Two years after the divorce, Shui Lu was remarried to the director of the Central Intelligence Bureau, Mr. Shen Tze Yuan (沈之岳), but David never married. Mr. Shen is known in Taiwan as the “Father of Intelligence.” When I met him many years later, he was already retired and devoting all his time to Christian ministry.

I am so glad that before their divorce, David and Shui Lu lived for a brief time in Toronto, while I was still teaching at Trent University in Peterborough. We were able to visit them on some weekends. Here is a photo of their new home in Toronto (above). They have two children, one boy and one girl. His daughter took after her mother and was interested in dancing. In 2013, when I spoke in Taipei, she came to visit me.

I am so glad that before their divorce, David and Shui Lu lived for a brief time in Toronto, while I was still teaching at Trent University in Peterborough. We were able to visit them on some weekends. Here is a photo of their new home in Toronto (above). They have two children, one boy and one girl. His daughter took after her mother and was interested in dancing. In 2013, when I spoke in Taipei, she came to visit me.

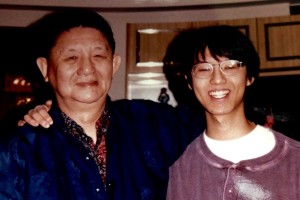

Much to his disappointment, his own son was interested in banking and business rather than in science. Naturally, David became very fond of my son Wesley, who has the same interest and talent in science. He often phoned my son to discuss research and the Bible without realizing the time difference between Taiwan and Boston. Here is a photo of David and Wesley, taken, at my Mom’s home in Hong Kong.

Much to his disappointment, his own son was interested in banking and business rather than in science. Naturally, David became very fond of my son Wesley, who has the same interest and talent in science. He often phoned my son to discuss research and the Bible without realizing the time difference between Taiwan and Boston. Here is a photo of David and Wesley, taken, at my Mom’s home in Hong Kong.

I am grateful that David took care of Mother during her last ten years of life. When David was born, my parents named him Wong Chi Hsian, which literally means Look Up to Wang Hsian. During his younger years, he did not have much time for his parents, but during his “forced retirement,” he was able to practice filial piety.

His Battle with Cancer

While living with my parents, he began to develop a tumor on his right neck just behind the earlobe. At first, it was just a small growth, barely visible. He simply dismissed it as unimportant. “It will go away,” he maintained. But it continued to grow. In my annual visits to Hong Kong, his tumor got bigger and bigger; what first was the size of an egg became the size of a tennis ball.

It took us many years of concerted efforts to persuade him to see a doctor about his growing tumor. We had to use all the pressure tactics we could muster to convince him of the urgent need for immediate treatment. Finally, he agreed to come back to Canada for a biopsy, which was possible as he was already a Canadian citizen. After his medical visit, I phoned him immediately.

“What is the biopsy result?” I asked anxiously.

“Not good,” David answered. He sounded uncharacteristically dejected.

“Is it cancer?” I pursued.

“Yes.”

“What are the treatment options?”

He began to stutter like my mother whenever she was anxious or upset. I could hardly make out his convoluted response, but the gist was that he was not going to get any treatment. According to the medical opinion of his case, the probability of survival after surgery and chemotherapy was no better than 50%. On the other hand, if he refused treatment, he would die for sure within three months.

David decided against surgery. He would rather enjoy his life for three months without disfiguring his face and suffering the horrible side effects of chemotherapy. He made that difficult and apparently correct decision way back in October 1995. He enjoyed a rather good quality of life for almost twelve more years! He doctored himself by trying all sorts of cures, from Australian shark’s cartilage to experimental drugs.

After my parents’ death, he moved back to Taiwan and lived by himself in a low-cost home for retired solders. He refused to let me see his room when we were in Taiwan—I think he felt embarrassed. About five years prior to his death, he suffered a stroke and was partially paralyzed on the left side. Even after recovery, he still had some speech impediment. The last time I visited him in Taipei in December 2006, his tumor jutted out like a salami—a nasty-looking thing with blue and purple colors at the end. He had to drain it several times a day and let out two or three bowls of blood on a daily basis.

Yet, he was unbowed by fate and unafraid of death. He limped slowly with a cane, but his carriage remained dignified, with his back erect and his chin up. His lips were always tightly closed, showing determination and strength. He totally ignored all the passers-by who stared at his monstrous tumor. There was only a slight touch of gray in his hair. His eyes were focused and intense as ever, and his mind was still very sharp even though he had developed some sort of “conspiracy” paranoia because of his traumatic experience and bruising legal battle for justice. He was worried about eavesdropping.

During my last visit to Taipei, as soon as I finished delivering all my lectures, my wife and I invited him to his favorite American-style restaurant for dinner. He ordered a beef steak, medium rare. “I need to eat a lot to compensate for the daily loss of blood,” he said almost apologetically for feasting on red meat. Well, why not? He needed to eat to feed his body and his cancer. He wanted to eat what gave him strength and joy. He was in a happy mood that evening. He frequently reminisced about our childhood days. After sharing many memories and laughter, we sent him home in a taxi. He waved goodbye with a smile before the taxi sped away. Right there and then, I was overcome by a profound sadness—I knew that I would never see him again.

In July 2007, I got a call from our sister that he had just passed away, surrounded by his grown up children and ex-wife Shui Lu. The irony was that he died of pneumonia rather than cancer. He had indeed succeeded in keeping cancer at bay. His defiant spirit and alternative medicine must have helped beat back the deadly disease.

Zest for Living

He was larger than life in both his failures and successes, in his weaknesses and virtues. There was a childlike quality about him. He simply plunged into the torrents of life with total abandon, undeterred by danger and unconcerned about what others thought of him. His naivety made him very vulnerable politically and socially. He was outspoken to a fault. His brutal honesty was often offensive and hurtful to those who did not know him well. His self-confidence smacked of hubris. His courage was often foolhardy. To him, there were only two kinds of people—smart or stupid, and he only respected the smart ones. His tendency to view people only through the lens of intelligence did not win him many friends.

As a contrarian with his unique insight on everything, he was a misfit in the work-a-day world. Because of his lack of relational skills and tact, he often unwittingly stepped on people’s toes and, eventually, he was stabbed in the back as payback. When he was unjustly framed and fired, nobody came to his rescue. However, to the end, he remained a truly original character—brilliant, creative, and arrogant yet hopelessly naïve. Even his defeat was magnificent purely in terms of the epic nature of his struggle. He waged a two-decade-long legal battle against powerful figures and institutions, demanding justice. He stared them down and stood his ground for truth and justice.

His life was full of passion and tragedy, splendor and darkness. He came, made his splash, and was gone, but he was one of the most influential characters in my life. He touched my life in a very deep way. For all his failings and eccentricity, David was unparalleled in his zest for living and in his grit against a hard fate. His fighting spirit and passion for life never wavered even in the darkest moments. He never gave up, never accepted defeat, and never felt sorry for himself—at least, he appeared that way.

In his few last years, in addition to reading several newspapers, and discussing political affairs with whoever was willing to talk to him, he spent much time reading Chinese Classics and the Bible. He dismissed TV as an idiot box for stupid people.

During my lecture tour in Taiwan in 2013, Shui Lu invited me and my wife to have dinner with David’s son, daughter, and grandchildren. We had several pictures taken after dinner. His son was doing very well in trading with offices in Shanghai and Taipei. His daughter was an architect with dancing as her hobby. I was so glad that his children had learned from both his glorious successes and miserable failures.

During my lecture tour in Taiwan in 2013, Shui Lu invited me and my wife to have dinner with David’s son, daughter, and grandchildren. We had several pictures taken after dinner. His son was doing very well in trading with offices in Shanghai and Taipei. His daughter was an architect with dancing as her hobby. I was so glad that his children had learned from both his glorious successes and miserable failures.

For myself, he has trained me well to confront the hardships of life with courage and grit, of which he remains an epitome. In spite of all his faults, his life has given me valuable insights into true grit. He showed me that grit is beyond mere success in achieving long-term goals. More importantly, grit concerns one’s integrity and authenticity, as well as the intrinsic value and worth of life.

With prolonged failure, eventually, passion fades, the resolve to persevere wavers, and the prospect of success vanishes into thin air. What kept David moving forward and living with zest was an unshakable belief in his own worth and dignity, and his intrinsic motivation in pursuing the ideal of justice and truth, regardless of the cost and outcome. Sadly, the world had no room for such an authentic person; but when he departed, he left this world a better place.

References

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.