Dr. Paul T. P. Wong’s autobiography, A Lifelong Search for Meaning: Lessons on Virtue, Grit, and Faith, is published in weekly installments. Stay updated here.

This evening is bleak and rainy, one that brings back many memories of my days in Vancouver. With this melancholic frame of mind, I recall the scene (情景) of my visit to the “Rain City” in the June of 2008.

Knowing the seriousness of my brother Benedict’s deteriorating health condition, I made a special trip to see him. By that time, he was already reduced to a skeleton wrapped in skin—a mere shadow of a former body builder. Cancer was about to claim another hero, a once consequential figure (風雲人物) in Hong Kong.

His big head and large eyes looked too heavy for his frail body. When I came into the room, after some struggle, he managed to stand up briefly and walk slowly towards the kitchen door, which led to the backyard. He opened the door and, in silence, his sad eyes lingered over the garden. “It is so beautiful here, full of greenery and fresh air,” he said softly and affectionately. I could sense his reluctance (不捨得) towards bidding farewell to his lovely home on earth.

“All my life, I have battled in the world of the Sopranos; my only regret is that I should have treated mother better (我這輩子在江湖上闖蕩; 唯一遺憾是對媽媽不夠好),” he reflected, as if speaking to himself. Then, with a hint of a bitter smile, he philosophized, “Well, it is worth it to go through this transient world (在大千世界走一趟 是值得的; see Buddhist Cosmology). Indeed, Benedict lived passionately and fought heroically. In spite of his many struggles and troubles, he also had moments of love, familial joy, and creative triumph. These meaningful moments, all by themselves, were reason enough to make life worth living.

Before we left, Benedict gave me a glass teapot, hand-made by one of his artist friends. He wanted us to remember him with this gift. As I shook his hand to say goodbye, I held back my tears, knowing that it would be the last time.

Two months after our visit to Vancouver, Benedict decided to spend his remaining days in a hospice. I am most grateful that on September 21, 2008, during his stay there, he wrote a preface for my autobiography—this was to be his last piece of writing. He was too weak to hold a pen, but, with some difficulty, he managed to dictate it. He passed away on October 15, 2008, surrounded by his wife and children.

Passing On the Baton

Down through the ages, as mortals, we seem so helpless and hopeless as the rushing tides of time carry us away into oblivion. The poem of Su Tungpo (蘇東坡) comes to mind:

The Yangtze River flowing east

Surging torrents wash away

A thousand years of famous men…

Life passes like a dream

Let’s drink to the river and the moon

In one of Benedict’s journal entries, he expresses a similar sentiment, “Life is a hopeless struggle. Life or death, love or hate, we cannot escape our mortality. Let’s continue the futile fight and keep dreaming of happiness, like the singing cicada on the treetop (人生是一場絕望的爭鬥,不論是生是死,或愛或恨,都離不開這個範疇。我們絕望的爭鬥著,夢想著幸福,就像枝頭的鳴蟬。).”

During the last few months of his life, Benedict lamented that the world had not yet heeded his voice, “This society no longer needs voices of conscience… Who can turn back the tidal waves? (這社會不再需要「良心」與「喉舌」…… 誰能力挽狂瀾?)” I believe that he would be pleased to know that I have taken a hold of his baton, and continue the task of writing and being a voice of conscience.

It is unfortunate that Benedict died before he completed his autobiographical novel about three generations of the Wong family. It would have depicted the epic struggles of various family members in their search for love, happiness, and significance against the backdrop of a tumultuous political and social revolution in China during the 20th century.

Benedict told me that this would have been his opus magnum, the ultimate expressing of his writing talents and psychological insights. I would have been something like Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, delving into the existential angsts and moral struggles of the Wong brothers.

I hope that my autobiography provides some of the raw materials of his unfinished masterpiece and gives a glimpse of the tragic lives of Chinese intellectuals caught in China’s earthshaking changes.

A Letter of Gratitude

Two months after I returned to Toronto, Benedict made the decision to check himself into a hospice facility. I felt that the least I could do for him was to send him an email to convey appreciation and gratitude. Here is the letter:

First of all, I want to thank you for your willingness to write a preface for my autobiography. Please do not spend too much time on this; just a few words from you would suffice.

Secondly, I want to tell you how much I appreciate your impact on my life in inspiring me to love literature and engage in creative writing.

Charles Dickens once said, “For as I draw closer and closer to the end, I travel in a circle nearer and nearer to the beginning. … My heart is touched now by many remembrances that had long fallen asleep.”

Indeed, my journey back to my early life has brought back many memories. To reconnect with one’s past is to gain a fresh appreciation of the significant people in one’s life. There is such a rich source of happiness and meaning in looking back.

While you were still a student at Pui-Ching Middle School, you already distinguished yourself in writing. You published regularly in the popular SingTo Daily’s Literature Page for Students (学生园地) where several famous Chinese writers have cut their teeth. You inspired me to contribute to SingTo, only to be rejected over and over again. This was my first taste of rejection while I was just 14.

You introduced me to your library of contemporary Chinese literature. I was particularly fond of a volume of poetry, Songs of the Night by He Qifang (何其芳). I was deeply moved by its beauty and yearning for love, and it started me writing poems as well.

I was privileged to get to know some of your famous writer friends, 黃思聘, 夏侯無忌, and 力匡. I was able to publish some of my poems in their literary magazine, Everyone’s Literature (人人文學), when I was still in high school.

I’ve always envied your literary talent—your gift of telling a moving story with a precise and elegant style, and your ability to inject meaning and poignancy to the fleeting moments of everyday life of ordinary people.

Above all, I admire your courage to pursue your dreams and become what you were meant to be. To be an authentic voice to a lost generation in China means financial hardship and alienation. But you have been true to your calling in spite of personal costs.

Alas, the snow-mountains and roaring rivers endure, bearing witness to more than 5,000 years of human suffering, yet the wheel of life moves on. Our family bond has sustained us through trying times, and we are much blessed by a loving family and devoted children.

In the midst of illness and death, we can still celebrate the preciousness of life. One blessed moment of being alive and loved is sufficient to dispel all the darkness surrounding us. I wish you many such moments.

As the physical world fades away, the spiritual reality looms larger. By embracing our own mortality and transcending our limitations and earthly concerns, we can achieve a fuller life on a higher plane. May you experience the peace and joy of walking with Jesus to your heavenly home!

This letter was written on September 15, 2008. Benedict died on October 19 the same year. Later, I learned from his daughter Christine that, when she read my email to him, his facial expressions indicated appreciation for these words of validation and comfort.

During Benedict’s last two years in Vancouver, life was very hard. One can clearly see the existential struggles of a dying man in his journal entries (see Appendix A). However, he was happy that he was finally close to his children and grandchildren. His clan was growing, with three children and many grandchildren. His second son Lawrence often came to visit and play chess with him. However, his impatience and tendency of asserting control made life very hard for his wife.

During Benedict’s last two years in Vancouver, life was very hard. One can clearly see the existential struggles of a dying man in his journal entries (see Appendix A). However, he was happy that he was finally close to his children and grandchildren. His clan was growing, with three children and many grandchildren. His second son Lawrence often came to visit and play chess with him. However, his impatience and tendency of asserting control made life very hard for his wife.

Benedict was not a happy person even when he was well. Maybe, as Hemingway has said, “Happiness in intelligent people is the rarest thing I know.” He saw too deeply into the heart of darkness and knew too much about human suffering to feel happy.

Deep down, he felt bitter that, for all of his sacrifices and achievements, he was forgotten and abandoned by the world. Once a shaker-and-mover, but now a helpless cancer patient. Once a well-known author, but now an unknown immigrant. Without a driver’s lesson, he could not go anywhere without depending on someone. This was an added source of frustration for someone used to being in control of everything.

The transition from an active and influential life to passivity and physical decline can be very difficult without faith in a transcendental and eternal reality. If meaning can only be created through significant personal projects, then terminal patients are doomed to a meaningless existence. But even in sickness, our significance and meaning can be discovered through having faith and the right attitude even on our deathbed, as Viktor Frankl has repeatedly emphasized.

The chaplain and the physician at the hospice and his daughter Christine both tried to help make the necessary transition. From what I heard at the memorial service, he was able to accept the inevitable with peace and commit his life and death to Christ.

The funeral service was held in a Chinese Church in Vancouver, the home church of his family. At his funeral, a collection of his latest books were on display with an oil painting of his portrait by his artist son John Wong. The service was attended by hundreds of family members and friends.

I forgot exactly what I said in my eulogy at the funeral service. But I want to briefly review his life at both the personal and national levels so that my readers can see his impact on my life.

Born to be a Rebel

When Benedict was still a teenager, he was already actively involved in the adult world, wheeling-dealing with all kinds of questionable characters who were more than twice his age. He was involved in trading horses and buying and selling weapons. One day, I discovered by chance a pistol hidden inside an umbrella holder in our foyer. Somewhere else in the house, I stumbled upon a 12-inch dagger. I still have no idea where he got hold of all these weapons.

He would steal money not only from my parents, but also from the coat pockets of relatives and guests who came to our house for dinner. He needed the cash to finance his business transactions. One day, a stranger knocked on our door, claiming the Benedict still owed him money for the rifle he had recently purchased.

He was filled with an insatiable curiosity about life and the interesting characters of the adult world. Drawn by life’s mysteries and challenges, he frequently ventured out way beyond the confines of home, school, and neighborhood. By any standard, he could be classified as a delinquent who cut classes and transgressed the law. Somehow, he managed to stay out of serious trouble, except with our parents.

It would take an entire book to recount all the escapades he pulled off during his teen years. With all these extra-curricular activities, he did not do well in school. The classroom was far too restrictive for this precocious and adventurous boy!

On one occasion, he was severely punished by our mother for altering the failing grades on his school report card. Mother hit him so hard that the wooden duster broke. She muttered something to the effect that he must have been born with copper skin and iron bones. On another night, he came home late by climbing over the 12-foot tall wall, but accidently fell and laid in a coma for a couple of days. This was not the first time, and definitely not the last time, when he had a brush with death.

Mother was so worried about this incorrigible black sheep that she consulted Taoist monks and Buddhist temples to find a cure. One evening, upon the advice of one of the monks, she purchased a large live fish and let it go in the river. She told me that the fish would take away all Benedict’s troubles. After this unusual intervention, for some reason, Benedict was a changed person. He began to stay home more, devoting his time and energy to body building. He liked to pose in front of the mirror. In a child’s eyes, he looked like Mr. Universe.

In the winter of 1948, Father was on a business trip to Shanghai and my oldest brother was in Beijing, studying at Tsinghua University. One day, when we were extremely busy packing for our move to Hong Kong, one male servant tried to prevent us from taking our belongings, claiming that all our possessions had come under the possession of the poor when the Communists took over. Benedict was able to subdue him and help Mother complete the big move. He was only 16 years old.

A Rising Star in the Literary World

When he was still in high school, his literary talents were quickly recognized by his teachers, editors, and famous writers in Hong Kong. After his graduation from Pui-Ching in 1952, he chose to study English literature at the National Normal University, partially lured by the legendary Leung Shi-Chu (梁實秋), who was then chair of that department and took a special interest in him.

During his high school days, Father dismissed him as someone who “will never amount to anything” (沒有出息). His older brother ridiculed him for not knowing his own limitations (不自量力). Such put-downs only spurred him to pursue writing with greater efforts. During his time at university, he quickly established himself in the literary arena, publishing short stories regularly in all the major literary periodicals, such as Literature Periodical, Pure Literature, Literary Star, and Free China.[1]

Xia Ji-An (夏濟安), a professor and famous writer, declared that Benedict was a “budding genius.” In the early 50s, Benedict was one of the rising stars, along with Yu Guangzhong (余光中) and Li Ao (李敖 等). While he was still an undergraduate student, Benedict already published several books, such as The Sudden Storm (暴雨驟來) and The Return of Kong Toon (康同的歸來).

Married to a College Queen

Benedict’s free and audacious spirit from childhood prepared him for his literary success, but also doomed him to be a failure in married life. Being a dashing and handsome young man, he attracted a string of girlfriends. His self-assured attitude of being a literary genius made him stand out in the eyes of female students in an era when writers were treated as today’s film celebrities.

As a freshman, Benedict was thrilled about beating out his rivals and capturing the heart of then-college queen Liu Pingsoon (劉秉松), who was in her last year of the same university, majoring in the arts. Ping is an accomplished artist. I am proud that I have two of her paintings hanging in my living room.

However, he was ill-prepared for the responsibilities of getting married and raising a family at a very young age. He must have felt burdened and stifled by the demands and restraints of the married life. His creativity fed on freedom and adventure. He wanted to live his life on his own terms.

His initial romantic passion, fueled by his poetical imagination, did not pass the reality test. Gradually, his affection towards Ping gave way to resentment. At that time, it was very hard to earn a living as a freelance writer; he described himself as a writing machine (爬格子的文人), dependent on submitting stories and articles to support a growing family. I remember that in the 50s, when I sold a 3,000-word short story to a newspaper, I only earned 30 HKD.

The couple began to drift apart in the early 60s when they moved to Hong Kong to live with my parents. He taught in a Catholic High School and spent his evenings writing and editing. She was exhausted from looking after three young children and coping with the complications of living with the in-laws. They did not have the time and privacy to live as a couple.

A Literary Career

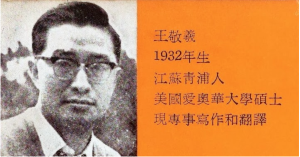

Benedict’s brief professional life can be viewed here. Here is a photo of Benedict in his early 30s, already an accomplished writer.

After his return to Hong Kong with his family in 1960, he continued his prolific literary output, publishing several books, including novellas, short stories, and essays.[2] Later he ventured into the publishing business and opened the Culture Bookstore (文藝書屋). However, this new venture inevitably eclipsed his literary career. Over more than two decades, he edited and published three monthly periodicals: Pure Literature (《純文學》香港版), Perspectives (《南北極》), and Fortunes (《財富》). These publications reflected the diversity of his interests and a smart business strategy of appealing to both the high-brow and the average person. Many famous writers of the 50s and 60s in Hong Kong have contributed to his periodicals.[3]

Perspectives was a highly successful and influential news magazine that provided a platform for Benedict to fearlessly criticize the Chinese governments in Taiwan and Beijing. His series of investigative articles on the super-rich offended several business tycoons. On one occasion, he was offered a large sum of money to withdraw a story about one of the wealthiest men in Hong Kong; needless to say, Benedict rejected the offer.

Benedict spent two years on a fellowship at the prestigious University of Iowa’s International Writers’ Workshops from 1996-1997. This long separation caused further damage to an already strained marriage.

Shortly after Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997, Benedict’s publishing enterprise was bought off by a businessman and immediately shut down. A critical independent voice was forever silenced!

During this period of transition, he briefly moved his residence to Guangzhou (遷居廣州) and resumed his literary endeavors, though on a much more limited scale. He took an active part in literary symposia (文學研討會) in both Guangzhou Normal University (廣州師範大學) and Fu Guang University (佛光大學) in Taiwan. He also revived the publication of Pure Literature and revised two collections of his selected short stories: The Prisoner and the Fly (囚犯與蒼) and The Cradle and the Bamboo Horse (搖籃與竹馬). Both books were republished and distributed in mainland China.

In 1973, I sponsored Benedict’s family to immigrate to Canada, where his wife brought up the three children by herself. Meanwhile, he chose to stay in Hong Kong to manage his publishing business and bookstore, and visited the family occasionally, until he moved to Vancouver during his last two years of life. Ping managed to put aside all her wounded feelings and took care of him. It was very hard on her, but by God’s grace, she chose to do the right thing.

An Assessment of the Value of His Life

Life often invites people with open arms, but then it shakes them and tramples on them until only the toughest ones survive the winnowing. How many deadly blows can one absorb? How much pain must one endure? Some live a thousand deaths and die by a thousand cuts. Such hard fate has fallen on both of my older brothers. From a macro perspective, both of my older brothers were victims of political forces beyond their control. In their own ways, they fought a good battle, refusing to give in to fate. As a writer, Benedict’s life was even harder than David’s. In the political climate of contemporary China, writers were particularly vulnerable. Their publications could be banned; worse still, they could be incarcerated for expressing their thoughts. The Cultural Revolution alone has destroyed many writers.

As the world turns, the tides change (日月循环, 潮流轉折). Each era (時代) creates its own heroes and claims its victims. Very few serious writers can ride the tidal waves of change (腾跃的浪涛) without being pushed aside or buried under. They must confront the dual task of both assuaging their own tormented souls and fulfilling their heightened sense of social responsibility. In so doing, they risk not only financial loss but also personal safety.

From a micro perspective, the value of one’s life is judged by what one does with the card one is dealt, and how one faces their own mortality. The harsh reality of death challenges us to make the best use of our limited time on earth. Even the mightiest ones must surrender at the last gate. How many monuments and crowns are now covered by dust! But the good that one has done will live on in the hearts and minds of those who have been touched and changed.

In the midst of political and financial difficulties, Benedict survived not only by capitalizing on his talents, but also by cultivating his defiant spirit. He dared to do the impossible, and always had the courage to stand up to the powerful forces in life. His favorite line was borrowed from Hemingway, “A man can be destroyed, but not defeated.” This spirit is best captured in a photo of him during one of his visits to Vancouver before he moved there permanently. What clearly stands out are the sharp and sad eyes of a man burdened with the weight of his own personality and the deadly disease of cancer. He literally stared into a scary and uncertain future with courage and contempt.

His defiant attitude reflects the Confucian ideal of not yielding to unjust power and the corrupt peddling of influence. Such a virtuous attitude (清高) or transcendental spirit (士人的仙气) is generally characterized by having a proud bone (傲骨). His self-awareness of possessing this classic Chinese virtue enabled him to maintain a sense of dignity even as he faced adversities.

All his life, he was driven by the desire to explore the world and experience life to the full. Always restless and energetic, he searched for success, happiness, and love, but he mostly found disappointment, frustration, and loneliness. As a frontiersman, he was tough, determined, resourceful, and self-reliant. He was self-confident to a fault. His life was full of adventures and misadventures, full of victories and defeats. He represents the best of us and the worst of us. Kind and generous to those he liked, he was harsh and critical to those he despised.

He was never content with everyday mundane existence, yet his ideal world, by its very nature, was always beyond his reach. A legend in his time, he had his days in the sun, but after his retirement in Canada, he spent the rest of his time in the darkening shadow of death.

In my research on Benedict, I stumbled on an image of his handwritten poem as shown below. It is a precious find, and clearly indicates that to him, meaning in life was more than the subjective feeling of fulfillment; rather, he was concerned about the objective significance of his life—whether his impact would outlive his death.

I’m racing against time,

With no intent to give in, without any fear.

I want to leave behind my footprints;

I’ll not allow wind or sand

To wipe them clean overnight.

I have devoted considerable space to this chapter, not only because Benedict has had a great deal of impact on my life, but also because I hope that his life story will encourage my readers to live more intentionally and intensely in their own quest for existential significance. He did not find his answers in his struggle for existential significance in a chaotic world, but, at the end, he discovered what really mattered in life was his family and the saving grace of Jesus. In sum, he was a talented and courageous writer with character flaws. But on balance, his virtue was more than his vice, and his contributions outweighed his mistakes.

Notes

[1] 常在當日重要的雜誌像夏濟安主編的《文學雜誌》、林海因的《純文學》、萧孟能创办的《文星》、雷震的《自由中國》等刊物上發表小說。

[2]著有中篇小說《選手》、《奔潮山莊》等,散文集《觀天集》、《偶感錄》等,短篇小說集《聖誕禮物》、《青蛙的樂隊》等。

[3] These include Eileen Chang (張愛玲), Li Ao (李敖), Si Guo (思果), and Xu Su (徐速).

Appendix A: Looking into the Mind of a Dying Person

When Benedict was too weak to write, he spent most of the time on his bed and dictated his thoughts. His journal entries shed some light on his inner struggles to wrestle life from the jaws of death (死裏求生的掙扎). Here are a few selected entries.

August 8, 2006

Became a cancer patient this week. Everyday in the afternoon, I will go to the hospital to receive radiotherapy for five weeks (five times a week). After that, I will make a decision whether or not to receive surgery. (I refused to do chemotherapy at the same time.) Now, I am just another patient—neither a monster, nor a genius. This so-called incurable disease will test my will to live.

自本周起已成為一個癌症患者,每天下午來醫院作電療,此一療程將歷時5周(每週5次)。5周後再作決定,是否要開刀。(我拒絕了同時進行化療。)我只是眾多癌症病人中的一個,不是惡魔,也不是甚麼天才。這所謂的絕症,正考驗著我的生命力。

October 11, 2006

It is 11:00 in the morning, after I went to visit a specialist to determine whether it was advisable to replace the major surgery with a minor one. My fate is in the hands of other people, and I am feeling increasingly helpless. Authors from the previous generation, such as Chao Ju-Yen and Wong Si-Cheng, wrote about “navigating the ocean of life,” and the final end is still death. It is hard to sail across this ocean because eventually everyone ends up drowning.

今晨11時後要去見專科醫生,對病情作評估,看有無可能做一小手術代替開膛破肚大手術。此時命在他人之手,個人變得越來越有心無力。前輩文人曹聚仁、黃思騁等都寫過“漂過生命海”這一類的文字,最終仍是以死亡結束。看來漂過此海並非易事。最終仍是淹沒。

January 24, 2007

(Benedict returned to Guangzhou to sell his apartment.)

Returned to Guangzhou and felt like I was in another world. The streets are crowded with so many automobiles, so many people. There is even a traffic jam, with every car competing for an advantage. Guangzhou is now a city like Toronto; it is as if I can hear the call of life and feel the blood flowing through my veins.

回到廣州,有恍若隔世之感。街上仍是那麼多的車,那麼多的人。大塞車的盛況突然出現,眾車爭路,實在是盛世的奇景。廣州是一個象Toronto那樣的城市,我仿佛可以聽到生命的呼喚和血在脈管內的湧動。

February 11, 2007

Cancer will not let me go. Mr. Wu and Yeung Chuan-Guang both died from cancer, the former being the famous Qigong master, the latter being Asia’s “Iron Man.” If such heroes had to surrender to cancer, how can I survive? It is only a matter of time. I regret that I did not spend a few more days in Hong Kong in January.

痼疾捉住我不放。伍大哥、楊傳廣俱患癌而去世,前者是氣功名師,後者是亞洲“鐵人”,他們皆甘拜下風,我豈能倖免?時間長短而已。現在很後悔一月返港時未能多停留數日。

May 30, 2007

Returned to Vancouver yesterday. What a paradise on earth—a green canopy over my head, and a floral fragrance in the air. Here I nurture my sick body.

前日返抵VAN。此間綠蔭遮頂、花香滿街,是人間樂土。而我就在這裏養我的病。

June 27, 2007

Another month has passed by. My days are uneventful. Hope that I can still do something significant. Should I start writing my epic novel? This entire last year has been spent battling cancer. How much time do I still have?

這個月又將過去。日子平淡。甚盼能再有一番作為。我的長篇小說應該開筆了吧?過去這一年,一直在為病而作戰。不知生命還能延續多久?

September 28, 2007

Have not made a journal entry for some time; nothing worth reporting. Chronic disease has drained my spirit, and dreams has become my happy refuge. Difficult to end my life when my children are so good to me.

久未作劄記,因為乏善可陳。痼疾令我再無振作的機會,我的睡夢中的世界成為快樂之所。子女對我好,令我無法下決心結束這個生命。

November 26, 2007

The weather has turned cold. The temperature is about zero. I can only stay indoors, barely clinging to a feeble existence. Once a “hero,” but now, what an ending! Can’t fight against God’s will.

天氣轉涼。零度左右。我只有呆在室內,苟延殘喘。“一代英雄”如此收場!天意難違。

January 1, 2008

Today is the first day of 2008. I still cannot make up my mind about the surgery, even though my life is at stake. I still cannot decide whether to undergo surgery.

今天是08年的第一天。我仍然不能夠對開刀做出一個決定,雖然我的生命危在旦夕。還是不能夠決定要不要開刀。

This was his last entry. Shortly after, he underwent a major surgery but was not able to prevent the spread of his advanced colon cancer.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.