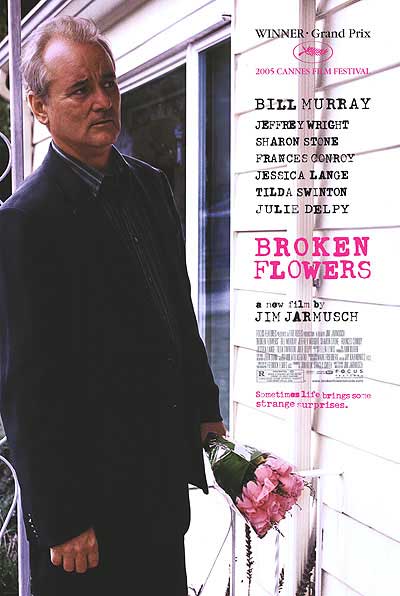

In spite of its sad themes, Broken Flowers is enjoyable. It is fun watching Bill Murray, the quietest comedian in Hollywood. In this film, Murray exhibits a masterful performance, telling an intriguing story with a minimum of words and expressions. As the story unfolds, the weariness and sadness on his face seem to deepen, but we can still find funny and quirky moments in droll Murray.

Murray is supported by a cast of strong and interesting characters who only accentuate Murray’s passivity. The footage of Murray’s long journey on the road offers a rewarding cinematic experience of the American landscape, capturing scenes from rural locales to metropolitan suburbs. Superbly directed by Jim Jarmusch with his trademark minimalist approach, this film won the grand prize at the Cannes International Film Festival.

The Story Line

The story is amazingly simple and clearly structured. Bill Murray stars as Don Johnston, a prematurely retired bachelor who has made his fortune in computer technology. The movie opens with him being dumped by his latest lover, Sherry (Julie Delpy). “You are just an over-the-hill Don Juan” is her parting shot. He reacts with indifference and detachment, but his silence cannot conceal his sadness.

Don sits alone in his rumpled track suit and falls asleep on the couch in the middle of the day. Most of the time, he sits there, perfectly still, with dropping eyes and doleful looks. Holed up in his dark home, with blinds perpetually closed, he seems resigned to the fact that life is passing him by. At this low point in his life, a mysterious pink letter from an anonymous former lover arrives at his door. This letter informs him that he is the father of a 19-year-old son who is looking for him. His initial reaction to this startling revelation is nonchalant—he just stares at the letter with the same blank expression. But something is stirring inside him, and he cannot simply dismiss the letter and continue in his vegetative state. He decides to consult his friend and neighbor, Winston (Jeffrey Wright).

Winston, an Ethiopian family man, works three jobs to support his growing family. He finds time to read mystery stories and play amateur detective. He gets excited about the pink letter, confident that with the right clues and methods, he can track down the mother of the supposed son. He also believes that the letter is a sign for Don to get out of the house and live again. After some painstaking research, Winston is able to track down four of the five likely mothers (one has died). He then maps out an itinerary and gives Don detailed instructions on what needs to be done to solve the mystery. In spite of Don’s protest that the trip is a stupid idea, Don finds himself dutifully doing exactly what Winston tells him to do—pink flowers in his hand, Mulatu Astatke on his CD player, driving a rental car to visit his ex-girlfriends.

His visit to Winston’s home provides some insight as to why Don finally agrees to embark on this difficult journey. There is so much love and life in Winston’s home. Don begins to think how different life would be if he could be united with his son.

The film is made up of four unrelated episodes of his encounters with his ex-lovers. On his first stop, Don calls on Laura (Sharon Stone) but is greeted by her vampy teenage daughter Lolita (Alexis Dziena), who sheds her bathrobe and offers Don a popsicle. Don runs out of the house when Laura returns home after work. A recent widow of a race car driver who met a fiery end, Laura remains an upbeat and energetic single, but her bubbly persona seems hollow as she enthuses about her job as a closet organizer. She cannot find a suitable vase for the bouquet of pink flowers from Don, which suggests a drought in her love life. She manages to get Don to spend the night with her for old times’ sake.

His second house call takes him to Dora (Frances Conroy), who lives with her husband in an immaculate prefab house in a new housing development. The conversation around the dinner table is artificial and strained. Dora’s face looks like a dry, wilted flower—a pale shadow of her former self in an old picture. The only topic her husband cares to talk about is his profitable prefab business. There is a feel of emptiness and chill in the air, in spite of the nice furniture and flowers in the house.

Don’s third stop is at the office of an eccentric professional animal communicator, Carmen (Jessica Lange). The receptionist (Chloe Sevigny) gives Don a cold welcome. She reluctantly fits Don in for a quick catch-up because Carmen is solidly booked for the day. During the short encounter, Carmen is interested only in boasting about her professional success and her unique gift in communicating with pets. When asked what the cat on her lap is telling her about Don, her quick response is, “You have a hidden agenda!” Without any feelings, she sends Don away with his bouquet of flowers.

His journey gets even more depressing when he finds Penny (Tilda Swinton) in a junkyard and rural hideaway for bikers. Penny looks like a wounded wild animal, with eyes full of pain and anger. She does not want to see him. To make sure he gets the message, one of her rough biker friends punches Don in the face. As he struggles to get back on his feet, with the flowers littered in the dirt, Don notices a broken typewriter among a pile of junk. Could this typewriter be linked to the anonymous letter?

His final visit is to the graveyard where the fifth maternal candidate for his son was buried. To her, Don offers a carefully arranged bouquet of roses. Don stands in utter silence among the dead and fallen leaves, a stoic figure to the end. But on the last stop of his return journey, we notice a tiny tear rolling down his cheek. A silent teardrop sums up the emotions he has carefully concealed behind his blank expression. We do not know for sure whether the tear speaks of mourning of the loss of relationships, the pain of broken dreams, or the disappointment of failing to find his son, but we can sense the depth of his hurt feelings.

Near the end of his trip, at a diner, he shows kindness to a young man he has just met by buying him lunch. Could this young stranger be his son? Don chases after this young man, who runs away from Don’s questioning. He is now a changed man; he has finally come out of his lethargic existence to pursue something with passion and determination.

In the last scene, for the first time in his life, Don is fully alive to the sounds and sights around him. With his eyes wide open, he surveys the surroundings like an eagle hungry for a catch. His apathy is now swallowed up by life and the excitement of the moment. Awakened, quickened, and transformed, Don is now connected with what really matters in life. A new sense of purpose has taken hold. He can sense that a new beginning is in the air. What accounts for Don’s remarkable transformation?

Anatomy of Midlife Crisis

Don has achieved the American dream of “Freedom 55”—financial independence—owning a beautiful home and all the nice things money can buy. Also, he seems to be equally successful in his love life, having had a long list of beautiful women in his past and being free to do whatever strikes his fancy. But why is his life so lonely and empty? Why does he look so weary and depressed? What has happened to his urban tribe? Where are the drinking parties? Why does he cut himself off from the world of living? What is going on in his head as he sits in the dark and gazes into the void?

By all accounts, Don is going through male menopause, typically due to existential crisis compounded by androgen deficiency (Hermans & Oles, 1999; Tremblay & Morales, 1998). With significant time on his hands and enough money to do whatever he wishes, he finds himself trapped in his house, not knowing what to do with the latter half of his life. His depression stems from a profound sense of existential anxiety (Yalom, 1980)—meaninglessness, hopelessness, loneliness, and death anxiety. He has nothing to live for and nothing to look forward to. He is likely to continue in his semi-catatonic state until something or someone intervenes.

In this case, the wake-up call comes from his caring neighbor Winston. Don suspects that Winston might have set up the whole thing—the anonymous letter and the subsequent journey into the past. In addition to being an amateur detective, the multitalented Winston is a pretty good lay psychologist, because he prescribes exactly what Don needs according to the best of psychological knowledge.

The Quest for Meaning

According to Erik Erikson (1993, 1994), the identity crisis for middle age is generativity versus stagnation. Don has certainly reached a state of stasis; he needs to shift from self- absorption to generativity—investment in the next generation and productive engagement with society. In this stage of the midlife crisis, both men and women ask the big questions about their personal identity and life purpose: What am I doing here? What have I done with my life? This self-focused questioning will not go very far until they begin to ask, How can I contribute to the next generation? How can I care for my family?

Winston knows that Don needs to re-engage with life in a productive way, but it requires something hopeful to draw him forward. What better way to reignite his hope and kick start his drive toward generativity than give him the prospect of finding his own son? Winston also seems to understand that Don needs to revisit his past to rebuild his future, taking into account past failures and regrets (McAdams, 2005).

Thus, Winston sends Don on a long journey to the past to experience the generosity of love offering (bouquets of flowers) to his estranged lovers. It will be a journey of healing, reconciliation, and redemption through loving and letting go. It will be also be a journey of self-discovery—to rediscover his passion for living (Cohen, 1999, 2001).

The four ex-lovers represent four chapters of Don’s past. Laura represents the shallowness of irresponsible, youthful hedonism. Dora represents the empty promises of wealth. Carmen represents the utter failure of human relationships based on meeting selfish needs and personal agendas. Penny represents the bankruptcy of the counterculture of easy riders. Finally, the grave of an unnamed lover represents the inevitable destination of all human journeys. By the end of his life review, Don is chastened rather than beaten, sadder but wiser. Realizing that he has gone to all the dead ends of American culture, he begins to appreciate the need to care for someone and something that will outlast him.

In existential psychotherapy, the action of meaning seeking and meaning making plays an important role. The key to Don’s transformation is action—embarking on a risky journey into the past, making a generous offering of bouquets of flowers to ex-lovers, and searching for significant clues in a junkyard. It is not how he feels and what he thinks that matter most but what actions he decides to take. All along, even toward the end of the journey, Don believes that the idea of the trip is stupid and that it has not changed anything in his life, but his actions tell a different story. He is searching, running after someone, and getting reconnected with life.

Another important element in Don’s successful navigation through the midlife crisis is that Winston leaves nothing to chance. He provides a detailed itinerary and instructions to facilitate the search for Don’s son. Psychology has indeed provided a roadmap and helpful instructions on how to restore meaning and hope (Erikson, 1994; McAdams, 2005; Wong, 1998). What is needed is a caring friend or therapist to make the information available to all the boomers who are mired in their midlife existential crisis.

References

- Cohen, G. D. (1999). Human potential phases in the second half of life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 7, 1–7.

- Cohen, G. D. (2001). The course of unfulfilled dreams and unfinished business with aging. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 9, 1–5.

- Erikson, E. H. (1993). Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton.

- Erikson, E. H. (1994). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: Norton.

- Hermans, H. J. M., & Oles, P. K. (1999). Midlife crisis in men: Affective organization of personal meanings. Human Relations, 52, 1503–1426.

- McAdams, D. P. (2005). The redemptive self: Stories Americans live by. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Tremblay, R. R., & Morales, A. J. (1998). Canadian practice recommendations for screening, monitoring and treating men affected by andropause or partial androgen deficiency. Aging Male, 1, 213–218.

- Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111-140). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2006). Anatomy of midlife crisis: From broken dreams to the quest for meaning [Review of the film Broken Flowers]. PsycCRITIQUES, 51(46). doi:10.1037/05228712

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.