Abstract

The best possible leadership in turbulent times is a visionary, competent leader who serves others with the twin power of faith and sacrificial love. This chapter explains why the self-transcendence model, the core of existential positive psychology (EPP or PP2.0) is needed for implementing servant leadership (SL) and capable of integrating the SL literature. We then propose the servant leadership profile-revised, with its 360-degree measure, as a promising tool for servant leadership research and present some new validation data. Finally, we introduce the best practices in servant leaderships and discuss its limitation and future implications. We conclude that in today’s climate, servant leadership represents the highest ideal for moral and selfless leadership for the greater good; therefore, even though it is difficult to implement, society is still better served when we aim at this ideal for leadership and good work.

Keywords: servant leadership, spirituality, Jesus, existential positive psychology, self-transcendence, humility

(This book chapter was co-authored by Paul T. P. Wong, Don Page, and Theodore C. K. Cheung)

Introduction: The Current Need for Existential Positive Psychology (EPP or PP2.0)

The biggest untold story in positive psychology is that although suffering may terrify millions of people, true happiness and success is unattainable without suffering. This sums up the essence of existential positive psychology (EPP or PP2.0), an emerging new paradigm for positive psychology and positive management. At present, we may be going through the darkest chapter of the 21st century, but at the same time this era may offer the greatest opportunity for positive transformation (Wong, Mayer, & Arslan, 2021). In this chapter, we try to unpack the new science of flourishing through overcoming hardships and suffering in organizations.

The pandemic has turned the whole world upside down. Its economic impact is devastating with many industries crumbling and countless small businesses have gone bankrupt. COVID-19 has also created a real mental health crisis. In addition, we are facing international crises such as the Russian-Ukraine war. Domestically, increasing polarization towards vaccination and critical race theory has divided families and organizations.

At the level of individual workers, people are struggling with stress and negative emotions which may have a negative impact on their work performance unless they are probably regulated. A related problem is that the pandemic has contributed to burnout of workers, when they must do more because of fewer available workers.

There is also the additional stress related of working remotely. It requires self-discipline and flexibility to focus on work, while children are needing one’s immediate attention. A related issue is about how to manage surveillance of working at home during the pandemic. There is both the possibility and evidence that some workers take advantage of the system while working at home. Therefore, the challenge is to cultivate a sense of responsibility and mission in the work force.

In view of all the above challenges, how can people stay positive and optimistic when so many things have gone wrong? What can psychologists do to help organizations and individual workers maintain a sense of tragic optimism and rise from the ashes? We propose that the EPP may be what we need in an upside-down world.

The Need for EPP

Elsewhere, Wong (2019a, 2021b) has made the case for PP2.0 because positive psychology as usual (PP1.0) is no longer adequate to meet the challenges of the COVID-19 era, with its single-minded focus on positive emotions and positive traits, given that suffering has become an undeniable reality of daily life (Wong, Mayer & Arslan, 2021).

In Wong’s (2022) recent foreword to a new positive psychology textbook by Piers Worth (2022), he sums up the reasons for PP2.0 as follows:

“The pandemic has shifted the focus on what is positive to a more realistic view of seeing the brightest stars in the darkest night – true positivity according to existential positive psychology. This is shift is like changing the course of the Titanic towards a more balanced view of the good life.

The dominant narrative of positive psychology is to fill our lives with positive experiences and emotions in order to live the good life. An alternative vision is that life is a balancing act (Wong, 2011). The most fulfilling life is one of harmony when we learn to embrace and transcend its duality of the good and bad times, as represented by the ancient symbol of Yin-Yang.”

Historically, EPP is rooted in existentialism in general, Frankl’s (1946/1985) Logotherapy in specific, and it has been articulated by Wong (2011, 2019a). Simply put, EPP is about how to integrate the positive psychology of happiness with the existential psychology of suffering (Wong, 2019b) in order to achieve sustainable wellbeing. EPP is able to develop a theory of global wellbeing by addressing the fundamental paradoxes and dilemmas of human flourishing through suffering. The following 3 principles capture the essence of EPP:

- True positivity is the ability to see the light in darkness. That means that you can see the brightest stars in the darkest night. “You can have an invincible summer in the dead of winter,” according to Camus. This paradoxical principle enables people to remain optimistic even in the worse of time.

- If you want to have success, you must come to terms with the dark side of life – inner demons and human evils. Until you embrace all the dark side, you cannot get to the other side of all the things that you dream of. All your dreams are on the other side of fear and suffering. If you want true success, do not avoid suffering and pain, but embrace suffering and pain, embrace failure. That is the sure guarantee to achieve a breakthrough sooner or later to reach a dream.

- The good life is not about being happy most of the time but navigating a balance between positives and negatives. The best possible life is a bittersweet life, rather than a life that only knows sweetness.

In sum, we need to cultivate a culture of embracing the dark side of life without fear of suffering, because evil and suffering are necessary aspects of human existence. If we want complete wellbeing or wholeness, we need to live with both the good twin and the evil twin, light and darkness. Complete wellbeing depends on an optimal balance between these two forces in organizations as well as in individuals. We are making the case that when people are armed with the mindset of EPP, they would be better equipped to deal with all the problems and misfortunes they face at work and in life.

EPP offers the necessary framework for positive transformation because it is more open for change by embracing human beings in their entirety with their potentials for both goodness and evil (Wong, Mayer, Arslan, 2021). EPP argues that positive change is more likely through confronting the dark side and digging deeper into ourselves for creative solutions.

A Self-transcendence Model of Servant Leadership and Good Work

Self-transcendence is the core of EPP (Wong, Mayer & Arslan, 2021). The self-transcendence paradigm focuses on rising above and integrating the bright and dark sides of life as two sides of the same coin. Without accepting this basic premises, it is difficult to practice servant leadership.

The Need for Self-transcendence (ST)

ST is at the heart of PP 2.0 for human flourishing in difficult times (Wong, 2011, 2021b). More specifically, ST represents a way of life and a way of overcoming all the inescapable suffering and limitations in order to achieve enduring happiness and flourishing (Wong et al., 2021). Recent research recognizes two broad paths to achieve success (Geher, 2022). ST represents the road less travelled for success and happiness (Peck, 1978), but it is also the most promising way to live a successful life even in the worst of times because it avoids the problems of an inflated ego (Holiday, 2016) and it allows one to be aware of one’s own brokenness and one’s need for positive change.

When Viktor Frankl faced imaginable horrors in Nazi death camps, he chose to react with courage, faith, and self-transcendence rather than depression and suicide. Frankl’s answer was to say “Yes” to life, no matter what (Frankl, 1946/2020). He has demonstrated that one can survive and overcome almost anything if one can consult one’s spiritual or noetic dimension, which will reorient one’s life attitude away from egotistic concerns to doing what is right and creating values to the life of others. Thus, the best way to flourish is through the gate of suffering. Making suffering the rock-bottom foundation allows one to build a sustainable business or sustainable life (Wong, 2020b).

ST is a process as well as a habit that needs to be cultivated daily. ST begins with self-reflection and self-awareness. Self-awareness happens when you are willing to remove your blinders, and remove the mask, the persona; when you are willing to face a naked self with all your inherent limitations. When you become aware of your need for repentance, and your need for some improvement, then you are ready to make baby steps to on your journey towards your highest ideal by faith in spite of the obstacles and uncertainty.

Faith allows you to overcome all the oppositions and scale the highest mountains. By faith, you will do the right thing against all odds and oppositions. That is why faith gives you the power to achieve a meaningful life and attempt the impossible regardless of circumstances. Faith and self-sacrifice for the greater good are the better angels that make you a better person and make this world a better place.

Viktor Frankl’s basic principle of the will to meaning refers to the innate primary motivation to purse meaning as something greater than oneself. Thus, the search of meaning equals to the pursuit of self-transcendence. Everyone has the inherent needs for meaning, which can be experienced best in self-transcendence (Wong et al., 2021). Frankl, (1946/1985, p. 133) offers the following definition of ST:

“Self-transcendence denotes the fact that being human always points, and is directed, to something or someone, other than oneself—be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself.”

The Centrality of Meaning and Self-transcendence

There is a large literature to support the assertion that meaning is equally important for life as it is for work, since a major part of adult life is related to work. Meaning is the foundation for wellbeing (Hicks & Routledge, 2013; Wong, 2012a). With respect to leadership, meaning or ST has the following important functions of leadership:

1. ST Provides a Moral Foundation for Leadership

ST contributes to ethical behavior. Pawar and colleagues (2020) report that servant leadership is linked to ethics, virtues, and morality according to a systematic-thematic literature review (SLR) of empirical research on SL. Self-transcendence provides the moral foundation according to Graham and colleagues (2011). In terms of values, Schwartz’s (2012) research proposes that self-transcendent values include universalism and benevolence as opposed to self-enhancement (achievement and power). ST seeks to transcend and integrate the opposite. According to the Short List of Universal Moral Values (Kinnier et al., 2000), there are 4 basic aspects of universal morality, which are consistent with the characteristics of ST:

- Commitment to something greater than oneself (self-transcendence or spirituality)

- Self-respect (Personal responsibility and conscience)

- Respect for others (The Golden Rule, common humanity)

- Caring for living things and the environment (Ecology)

2. ST Awakens the Spiritual Dimension in Individuals and Organizations

Self-transcendence provides a conceptual framework for both theistic and

non-theistic spirituality with its emphasis on transcendental values, which are badly needed in a secular and consumer society. ST provides a spiritual vision for the future of humanity that emphasizes the spiritual and humanistic values of selfless love and serving the common good

Widodo & Suryosukmono (2021) consider that the spiritual leadership style and the spirituality factor in the workplace are reflected in the form of self-transcendence.

The purpose of their study was to examine and analyze the relationship between spiritual leadership and spirituality in the workplace towards self-transcendence and realizing meaning in work (Meaningful Work). According to Wong (2003), there is a huge literature on the adaptive benefits of religious beliefs and spiritual practices. Spirituality provides a framework to make sense of the big questions. Every culture develops their own religion and spiritual practices: “A healthy dosage of spirituality and meaning at the workplace is good for business, because it improves morale and productivity. This view is gaining currency among management consultants, human resources professionals and mainstream business schools.”

In order to cope with increasing feelings of stress and alienation, both managers and employees alike are trying to create meaning and purpose in the workplace. They are also searching for a renewed sense of community. The holistic approach towards management suggests that it is good for people to bring their whole persons to work, their body, mind, and spirit. In the face of economic downturn and global competition, it would be helpful to seek inspiration from Above and tap into employees’ spiritual resources.

According to Wong (2003), the full benefits of spirituality on morale and productivity will not be realized without a sustained, large-scale cultural transformation at all levels of the organization:

- Spirituality is about bringing passion – bringing your heart, soul, and spirit – to what you do because from a spiritual perspective, work has a deeper meaning and serves a higher purpose.

- Management learns to truly listen and builds a safe place where employees can speak the truth without fear of repercussions.

- Management will break down the walls of hierarchy to create a sense of community and inspire a sense of belonging in workers.

- There is a new willingness to reflect on the meaning of life and moral implications in making important decisions.

- There is a shared attitude that products and services need to be beneficial to community and humanity.

- Management will value employees based on who they are, what they can become, in addition to what they can do for the company.

- Bosses will treat employees in a responsible, respectful, and caring way because people are not instruments to be used and exploited.

- Management will also resort to spiritual ways of resolving conflict. Therefore, they will be reluctant in issuing an ultimatum and slow in pulling the “firing trigger”.

- There will be an improvement in morale, job satisfaction, loyalty, and productivity.

In sum, ST practices the spiritual law of loving others as oneself and serves as an antidote to our selfishness and suffering. It is similar to the Buddhist concept of no self or the Christian teaching of having our ego crucified with Christ on the cross, which would liberate us from our carnal desires and selfishness. Frankl stated that “what gives light must endure burning.” You become the light by transcending the dark side of life including your shadow, but more importantly you can become the light through self-sacrifice. To let yourself be a living sacrifice, a burning candle to drive away the darkness around you. Evil and suffering will always with us. Be the light of the world. To be a leader is to set an example of being a candle shining in darkness.

3. ST Emphasizes a Sense of Calling as the Most Important Motivation

As a leader or a worker, no motivation is more powerful than a strong sense of calling or mission; it is capable of inspiring people to do the most difficult and risk thing without money or recognition. According to Wong et al., (2017), one’s career has intrinsic motivation when it is regarded as a “calling” (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997) and good work is regarded as an achievement of excellence and ethics (Gardner et al., 2001).

A sense of calling or mission is important for both individual and organizational success. Research has confirmed that the importance of calling in terms of self-transcendence and meaning contribute to work performance in the long germ. This is acknowledged by Steger (2016).

The concept of Calling usually includes the following components.

- Based on one’s interest and talents

- Based on the demand and need of the situation

- Based on the felt responsibility to serve the common good

- Based on a sense of calling from the transcendental realm

4. ST Captures the Paradoxical Principles of Servant Leadership

In SL, we lead through serving, and we become the first by our willingness to be the last. Similarly, self-transcendence precedes self-actualization (Wong, 2016). As stated in the Bible (Luke 9: 23-24, NASB), SL is paradoxical:

“And He was saying to them all, ‘If anyone wishes to come after Me, he must deny himself, and take up his cross daily and follow Me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for My sake, he is the one who will save it.’”

Thus, the first paradoxical principle of ST is that one needs to be willing to be the last, as a servant for all, in order to lead effectively. Another related paradoxical principle is that one can save oneself from a life of meaninglessness by losing it for a higher purpose. Therefore, the humble attitude of servant leadership is difficult to achieve without the underlying change of life orientation from egotism to self-transcendence.

Psychology has begun to appreciate the value of a paradoxical approach. Smith and Lewis (2011) reviewed the literature of paradox theory and provide a compelling argument that a paradoxical lens is the most adaptive resolving competing tensions and resulting in creative outcomes. When organizations and multinational corporations become more dynamic and complex with increasing contradictory demands, such as conflicting values between East and West, a paradoxical approach may be more helpful in responding to such tensions. They present a dynamic equilibrium model of organizing, which “depicts how cyclical responses to paradoxical tensions enable sustainability.”

Contradictory elements (thesis and antithesis) resolved dialectically through their merger into a combined element (synthesis). Yet a new tension eventually surfaces as the resulting synthesis becomes a new thesis. Over the past twenty years, researchers have advocated paradox theory as a provocative and powerful lens for comprehending and managing organizational tensions (e.g., Lewis, 2000).

Paradox is an old concept. Its roots lie in ancient teachings across Eastern and Western thought, apparent in such works such as the Tao Te Ching and the Judeo-Christian Bible. More recent concepts of paradox draw upon the varied philosophies of Kierkegaard, Hegel, Hampden-Turner, and Weber and tap into the psychological insights of Freud, Rothenberg, and Watzalawick (e.g., see Lewis, 2000).

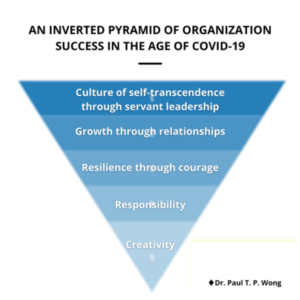

From the perspective of EPP, the new paradigm of self-transcendence is needed for servant leadership and the future of work in a rapidly changing world. The following diagram of an inverted pyramid (Figure 1) show the self-transcendence model needed for organizational success in the post-pandemic era or in trying times.

To a servant leader, human resources, not financial resources, is of ultimate importance. Understanding that life is a constant struggle and that anything worthwhile is an uphill battle against powerful enemies, a servant leader naturally cares about developing the potential of workers so that they can contribute their best.

To be effective, SL begins with the need to create a positive corporate culture of self-transcendence–- oneself in serving the common good as a humble servant (Wong, 2012b;; Wong & Page, 2003). This change is needed because the old hierarchical structure of command and control is not flexible enough for the brave new world when most people are working remotely, and decisions often need to be made quickly on the frontline without going through the long review-and-approve process. Furthermore, in a digital economy, knowledge workers need to develop their leadership potentials to make good decisions as part of a small team in a flat organization.

Figure 1

An Inverted Pyramid of Organization Success in the Age of COVID-19

When ST is applied to leadership, the implications are huge. In addition to opening up to the mysteries and wonders of the cosmos, thus, tapping into the boundless resources in the transcendental realm, a servant leader is devoted to serving others and a higher purpose rather than feeding one’s own ego. Therefore, ST is a natural antidote to all the problems coming from egotism – abuse of power, corruption, and violation of public trust. More importantly, self-transcendence demands a quantum shift in our life orientation from asking “What can I get from others?” to “What can I do for others?”

According to Tao Te Ching (Anderson, 2021), the main text of Taoism, the way of a servant leader is to be like water. By not exalting oneself and willing to go to lowly place where nobody wants to go, one is able to benefit all the people within the sphere of influence.

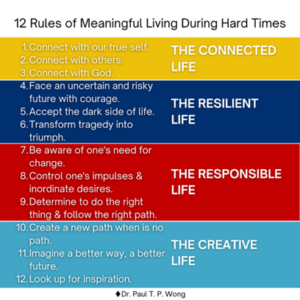

In addition to servant leadership, the ST model includes four modules of values necessary for flourishing through suffering. Each module is referred to as a triangle because it consists of a set of three interrelated values. Together, these values are the defining characteristics of SL:

- The Golden Triangle of innate motivation for connections with one’s true self and calling, with other people, and with God or a higher power.

- The Iron Triangle of summoning up one’s courage to face life in its totality, to accept the dark side of human existence, and to transform all painful experiences into triumphs.

- The Executive Triangle of taking the ethical and instrumental responsibility to do the right thing.

- The Creative Triangle of finding a path where there is no path.

These 12 values or rules for life are summarized below (Figure 2). Each of these 12 rules can be translated into a skill or competence that enables us to transcend our inherent limitations, vulnerabilities, and external constraints. Thus, self-transcendence is a lifelong learning process of how to grow beyond oneself.

Figure 2

12 Rules of Meaningful Living During Hard Times

In this chapter, we propose that SL practices meaning-centered leadership and produces good work (Wong et al., 2017). According to this view, good work exists at three levels: the individual, the organization, and society.

At the individual level, good work means that employees are empowered through intrinsic motivation to make the optimal use of their strengths, resulting in a high level of job satisfaction and productivity. At the organizational level, a virtuous servant style of leadership (Wong, 2004) unleashes the full potential of employees and provides a positive culture (Wong, 2005). At the societal level, good organizations assume their social responsibilities to contribute to the greater good beyond the bottom line. There is empirical evidence (e.g., Searle & Barbuto, 2010) that servant leadership could have a positive impact at all three levels of good work in terms of both productivity and virtuousness.

It is difficult or impossible to practice SL without embracing self-transcendence as a life attitude or core value, because it emphasizes such qualities as humility, integrity, responsibility, serving a higher purpose, fulfilling a mission, and the need to develop and release the creative potential of all workers.

Since no existing leadership theory emphasizes how to liberate us from human foibles and baser aspirations, such as abuse of power and corruption, servant leadership represents a promising and workable framework to keep these destructive forces in check in a systematic way, from cultivating personal responsibility for a higher purpose to developing a positive, virtuous corporate culture.

The Rising Popularity of Servant Leadership

There is increasing interest in servant leadership research during the past three decades. The concept and practices of servant leadership was first developed by Greenleaf (1977). Servant leadership encompasses valuing the personal development of individual workers (Greenleaf, 1977; Spears, 1995). This approach is effective, because employees who feel valued are able to grow and make a useful contribution. When Robert K. Greenleaf wrote about the idea of serving or servant leadership in the 1970s, it was as an antithesis to the abuse of power that he saw in contemporary American leaders. It was presented as a cohesive philosophy aimed at creating a more caring society by redirecting the power of the leader away from selfish ambition to serving and respecting those whom they led. During his lifetime, and despite his tireless promotional efforts, the idea did not catch on as being a servant and a leader seemed to be a hopeless oxymoron, until it was realized that a leader would not be denigrated by have a serving function. (Page, 2009, p. 64-65)

Over the years servant leadership has gained popularity among leadership scholars (Solinger et al., 2020; Stone et al., 2004). The idea of servant leadership began to gain considerable traction when noted scholars and writers in the field of leadership came to embrace and promote it, such as Max De Pree (1992), Peter Block (1993), Warren Bennis (1994), Stephen Covey (1994), Ronald Heifetz (1994), Margaret Wheatley (1994 ), Peter Drucker (1995), Calvin Miller (1997), Peter Senge (1997), John Maxwell (1998), Jeffrey Pfeffer (1998), and Ken Blanchard (2003) to name just a few. There was also a recognition that servant-led businesses could be successful, such as Southwest Airlines (Freiberg, 1996) and Synovus Financial Corporation (Page, 2009, p. 109-117)) and others at the top of Fortune Magazine’s Best Companies to Work For.

According to Winston and Ryan (2008) and more recently Canavesi and Minelli (2021), there has also been a significant widening of the published research beyond the United States (40.8%) to include China at 13.8% and Australia (7.7%), United Kingdom (7.4%), South Africa (5.8%), Canada (4.5%) and the remainder from the Netherlands, Hong Kong, Spain, and Turkey. (Canavesi & Minelli, 2021, p.13-14) From our research in the literature, we have found articles connecting servant leadership to attributes found in Italy, Portugal, Brazil, South Korea, Singapore, Ghana, Kenya, Saudi Arabia, Cambodia, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Rwanda, Indonesia, Philippines, and Viet Nam. In short, servant leadership has become a world-wide phenomenon that attracts attention and comparisons in both democratic and collectivist societies.

In her book, Rethinking Leadership: A Critique of Contemporary Theories, Annabel Beerel (2021) draws attention to “a distinct shift in the concept of leadership as being one focused on a capacity for doing to a state of being. There has also been a shift from the strictly behavioral learned skills approach to greater emphasis on the psychological maturity and strength of the individual (Beerel, 2021, p. 45).” With its focus on the development of the individual and one’s mindset for serving others, servant leadership is uniquely positioned to bridge this gap as the recent increase in published research studies has shown leading to a number of literature reviews by McClellan (2009, 2010), van Dierendonck (2011), Paris and Peachy (2012), Kumar (2018), Canavesi and Minelli (2021), and Chaudhry et al., (2021).

Critics of servant leadership have been quick to point out that the success stories were mainly antidotal and not empirically proven. Beginning in the 2000s, that began to change as reputable scholars published peer reviewed empirical studies showing the benefits of servant-led businesses. To begin with, a ground-breaking 10-year study by Magellan Executive Resources demonstrated that 11 servant-led companies were 24.2% profitable while the profitability of the average Standard and Poor’s 500 companies for the same period was only 10.8% and the much touted Jim Collins’ Great Companies averaged 17.5% in pre-tax profitability (Sipe & Frick, 2009, p. 199-200). Subsequent studies have shown the reason for this in terms of superior employee engagement and experience.

30 years of empirical research now shows that servant leadership is positively associated with the following job-related attitudinal outcomes: employee engagement, thriving at work, psychological well-being, positive work-life balance, job satisfaction, lower employee turnover rates, perceptions of meaningful work, family support, and reduced family conflict (Eva et al., 2019, p. 119). Some writers have sought to include servant leadership as a subset of the now dominant thinking on transformational leadership. In fact, while they have many similar traits, they are fundamentally different (Parolini et al., 2009). Transformational Leadership aims to benefit the organization whereas in servant leadership the benefit is for those individuals being served. Or, as Sen Sendjaya (2015), has characterized it, servant leadership is all about “people building” versus “people-using’ in transformational purposed organizations. This is not to suggest that servant leadership is not transformative but rather the transformation is for the primary benefit of those impacted by these transformative practices. What is important to note is that servant-led businesses consistently outperform transformational businesses in the same field in that they produce 10% better team performance, 11% higher employee satisfaction, 7% higher employee commitment levels, 11% greater longevity with the organization, 19% better citizenship behavior, 5% higher in-role performance, and 28% higher business performance. (Senjaya, 2015, p. 6)

There are now many great models of transformative servant leadership in action. In their book, Servant Leadership in Action, Ken Blanchard and Renee Broadwell (2018) give us a glimpse into the testimonies of 44 prominent contemporary practitioners of servant leadership drawn from the diverse fields of business, academia, non-profit organizations, military, sports, and spiritual. What they all have in common is that they are published authors who not only exemplify servant leadership in their own lives, but in their affiliated organizations. They give practical insights into “the power of love rather than the love of power” because servant leadership, at its core, is the giving of “love in action” (Blanchard & Broadwell, 2018, p. 247).

Recent Research on the Characteristics and Benefits of Servant Leadership

Several recent reviews illustrate the rising popularity of SL. The Hine Bibliography of Resources on Servant-Leadership, last published in 2008, has been revised and expanded significantly (Muyumba & Hine, 2015); it includes hundreds of studies. Chaudhry et al. (2021) wrote a review article of the servant leadership literature since its formal inception in 1970. Summarizing previous studies, they theorized and explored issues concerning the conception and relevance of servant leadership, the merits of varied measurements, issues concerning construct dimensionality, and the potential effects of national culture on the relationship between servant leadership and its correlates supported the distinctiveness of servant leadership from other types of leadership and showed effects of servant leadership on individual-level and unit-level outcomes, and supported theorized mediating effects of trust and fairness perceptions in the relationship.

According to Eva and colleagues (2019), servant leadership “is a holistic leadership approach that engages followers in multiple dimensions (e.g., relational, ethical, emotional, spiritual), such that they are empowered to grow into what they are capable of becoming. It seeks first and foremost to develop followers on the basis of leaders’ altruistic and ethical orientations (Greenleaf, 1977).” They suggested that servant leadership may be the leadership of choice for the 21st century because it frees people from egoistic needs.

Eva and colleagues provided an integrative and comprehensive review of 285 articles on servant leadership spanning 20 years (1998–2018) and offered a new definition of servant leadership. They offered a new definition of servant leadership in terms of 3 main characteristics:

“(1) other-oriented approach to leadership (2) one-on-one prioritizing of follower individual needs and interests, (3) and outward reorienting of their concern for self towards concern for others within the organization and the larger community”. The above three features are similar to self-transcendence, which is other-oriented, dedicated to bringing out the best in others, and with a broad pro-social and humanistic mindset.

van Dierendonck and Patterson (2014) introduces compassionate love as a practical translation for the need to serve, which was positioned by Greenleaf as the core of servant leadership. This article takes a virtues perspective and shows how servant leadership may encourage a more meaningful and optimal human functioning with a strong sense of community in organizations. In essence, we propose that a leader’s propensity for compassionate love will encourage a virtuous attitude in terms of humility, gratitude, forgiveness, kindness, and altruism. This virtuous attitude will give rise to servant leadership behavior in terms of empowerment, authenticity, stewardship and providing direction.

Recent research has identified five ways COVID-19 has changed workforce management (Kirby, 2020):

- Building a learning mindset of continued self-improvement.

- Being flexible and adaptive to a new routine of working remotely, a new routine where everyone must suddenly work from home.

- Building a culture of trust, transparency, and openness since people have to do work with less oversight.

- Caring about individual and social wellbeing because the pandemic has put pressure on workers’ wellbeing and private lives. Mandating and providing opportunities for workers to expand their mental health provision.

- Working in a more agile way.

All five points, especially points one, three, and four, are aspect of servant leadership. In other words, servant leadership naturally meets the needs for change in workforce management.

According to Witt (2019), the five most prominent servant leadership characteristics are:

- Valuing People. Servant leaders value people for who they are, not just for what they give to the organization. They are committed to people, particularly their followers.

- Servant leaders do not promote themselves; they put other people first. They are humble, not humble as an act. Servant leaders know leadership is not all about them but that things are accomplished through others.

- Servant leaders listen receptively and nonjudgmentally. They are willing to listen because they truly want to learn from other people. To understand the people they serve, they must listen deeply. Servant leaders seek to understand first, then to be understood. This discernment enables the servant leader to know when their service is needed.

- Servant leaders give trust to others. They willingly take this risk for the people they serve. They are trusted because they are authentic and dependable.

- Servant leaders have people and purpose in their hearts. They display a kindness and concern for others. As the term servant leadership implies, they are here to serve, not to be served. Servant leaders truly care for the people they serve.

A recent study (Barbuto & Millard, 2014) examined the impact of servant leadership on followers’ wisdom development and emotional labor. Taken together, these studies support prior claims that servant leadership fosters personal growth and emotional regulation in followers.

According to Canavesi and Minelli (2021), servant leadership is a holistic approach whereby leaders are concerned with the company’s stakeholders and followers in multiple dimensions, such as emotional, relational, and ethical, in order to bring out their full potential. Servant leadership has been linked through various mediators to positive individual and collective outcomes, including behavioral, attitudinal, and performance.

In a similar vein, Mayer et al. (2021) points out that the pandemic has changed both employees and organizations dramatically and research has identified six important factors for management during COVID‐19:

- Defining clear expectations in virtual work arrangements.

- Workers assuming personal responsibility for flexible time usage to get the work done and take care of family commitments.

- Maintaining or increasing trust between managers, virtual workers, and colleagues.

- Appreciating shared endeavors and organizational solidarity.

- Accepting stringent policies and collective actions during emergencies.

- A manager’s sense of coherence to perceive a stressful situation as understandable, manageable, and meaningful.

Their research findings highlight the importance of sense of coherence in buffering against stress in managers. Most of the six factors, such as personal responsibility, trust, acceptance, serving the common good, and see stress as meaningful and manageable are characteristics of a good servant leader.

Servant leadership is most suitable in the context of non-profits and social ventures. This influence is likely to be more commonplace in social ventures than in commercial ones. Evidence from social entrepreneurship research shows that many senior executives have left lucrative positions in corporations to start or to work in social ventures to achieve a sense of meaning through their work (Bacq et al., 2016).

In sum, the 21st century world needs servant leadership skills, with the life orientation of self-transcendence, in order to save it from self-destruction and another world war.

The Servant Leadership Profile-Revised

There has also been a significant evolution in the development of useful and verified instruments used for measuring servant leadership. Here we can see the influence on the designers of the earliest models through presentations and discussions at the Roundtable on Servant Leadership organized by Regent University in Virginia. The first multidimensional instrument was that of Farling, Stone, and Winston (1999) followed by Page and Wong (2000; Wong & Page, 2003), Russel and Stone (2002), Patterson (2003), Sendjaya (2003), Parolini (2004), Dennis and Borcarnea (2005), van Dierendonck and Heeren (2006), Barbuto and Wheeler (2006), Wong and Davey (2007), Liden et al., (2008), Sendjaya, Sarros, and Santora (2008), and van Dierendonck and Nuijten (2009).

Eva and colleagues (2019) have reviewed some of the most widely used SL measures. Going forward, for both future research and practice (leadership recruitment or development) purposes, we recommend three measures of servant leadership behavior that have gone through rigorous process of construction and validation, namely (in alphabetical order), Liden et al.’s (2015) SL-7, Sendjaya et al.’s (2008) SLBS-6, and van Dierendonck and Nuijten’s (2011) SLS. Each of these psychometrically sound measures is distinct, however, in its emphasis. As such which measure is most fitting to employ depends on the specific purposes of the study or program. What follows is a brief description of the relative strengths of each measure.

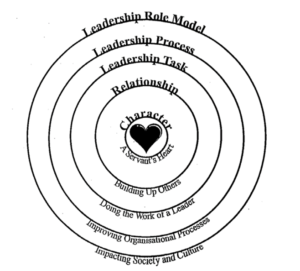

In terms of the identification and assessment of the construct of servant leadership, Wong and colleagues have developed two relevant instruments: a self-assessment of servant leadership (Page & Wong, 2000); and the 360-degree assessment of leadership (Wong et al., 2004). From a more practical perspective, Page (2009) has provided a detailed hands-on guide to transforming management to servant leadership.

Page and Wong (2000) proposed a conceptual model of servant leadership with servanthood at the heart of the model. They also developed an instrument that measured both the characteristics and the process of SL. The instrument was developed purely based on a prior conceptual analysis as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

The Process Model of Servant Leadership

Later, Wong and Page (2003) developed an opponent-process model of servant leadership and a revised Servant Leadership Profile based on empirical research. The significant contribution of the opponent-process model is that it explicitly identifies autocratic leadership as antithetic to the practice of servant leadership. In other words, it is not possible to be a servant leader when one is motivated by power and pride.

Based on a large sample (more than one thousand subjects), Wong and Page (2003) identified seven factors in their Servant Leadership Profile – Revised (SLP-R):

Factor 1: Empowering and developing others

Factor 2: Power and pride (Vulnerability and humility, if scored in the reverse)

Factor 3: Serving others

Factor 4: Open, participatory leadership

Factor 5: Inspiring leadership

Factor 6: Visionary leadership

Factor 7: Courageous leadership (Integrity and authenticity)

The SLP-R has been used by more than 100 organizations and universities for research and evaluation purposes. A 360-version has also been developed and used. We continue to receive requests to use the SLP-R from all over the world on a regular basis. It seems that more and more people have discovered the value of this instrument. Most recently, we completed a concurrent validity study of the SLP-R.

Method of Our Validity Study

Participants

A total of 59 student participants (Female: 69%) were recruited from Trinity Western University to complete the informed consent and questionnaires. The mean (S.D.) of their age was 36.9 (12.1) years old, ranging from 22 to 63 years old. They represented diverse cultural backgrounds with self-identified ethnicities from South Asians (34%), Caucasians (29%), South East Asians (19%), Aboriginals (7%), Indians (5%) and others (6%). Although majority of the participants were Christians (54%), other religions such as Sikhism (17%), Hinduism (10%), Islam (10%), Buddhism (3%), Atheism (3%) and others (2%) were also reported.

Procedure

The participants were invited to participate in the online questionnaire research on voluntary basis. They received a hyperlink from their course instructor to complete the study on a voluntary basis. Their responses remained anonymous. They were asked some demographic information. After that, they would fill in the 62-item Servant leadership Profile-Revised (SLP-R; Wong & Page, 2003), and the 30-item Servant Leadership Survey (SLS; van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). The research was approved by the Ethics Review Board of TWU.

Data Analysis

The primary goal of the data analysis was to establish preliminary psychometric properties of the scales, including the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha), and external validity.

Results

Despite the rather humble sample size, the participants covered diverse age, income, religion and ethnicity backgrounds. The Servant leadership profile-Revised (SLP-R) had excellent internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96. The scale also correlated with the SLS significantly (r = .07, p <.001), indicating a satisfactory external validity.

The Best Practices of Servant Leadership and its Limitations

According to Wong & Davey (2007) SL represents a radical approach in leadership development in a number of ways:

- It is humanistic and spiritual rather than materialistic and mechanistic

- It puts workers rather than shareholders at the center of concentric circles

- It motivates workers primarily through creating a caring and supportive workplace rather than through individual incentive system

- It is banking on an optimistic view of employees, believing that they will respond positively to leaders who demonstrate SL characteristics.

However, SL has its detractors. Basically, there are six common criticisms:

- SL is too idealistic and naïve. In an individualistic consumer culture, many people will take advantage of the servant leaders’ kindness as weakness (Johnson, 2001).

- It is too unrealistic and impractical. It would not work in many situations such as military operations or prison systems (Bowie, 2000).

- It is too restrictive, because we need all sorts of leadership qualities, such as intuition, risk taking and courage.

- It is too closely tied to Christian spirituality, because it is impossible for people to model after Christ’s humility without being redeemed and transformed by the Holy Spirit.

- It is too hypocritical – too many claim to be servant leaders but behave more like dictators.

- It is too foreign a leadership style, not only because the term is an oxymoron. but it also requires a fundamental change in values and life orientation.

There is some truth in all the above criticisms. For example, many CEOs are afraid that in the rough and tumble competitive business world, they would be perceived as weak and indecisive if they think and behave like a humble servant. Furthermore, in a highly competitive market, a leader does not have the luxury to seek consensus or widely consult employees before making a decision.

Admittedly, there are also limitations in the SL model, but the advantages of SL far outweigh its weaknesses. For example, SL is opposed to the command-and-control type of autocratic leadership. But there is now a clear consensus among modern management theorists (e.g..Senge, 1990) that autocratic leadership needs to be replaced by leadership that empowers workers.

In today’s environment, especially in a digital economy, command-and-control leadership no longer works, because leaders must earn people’s respect and trust. Servant leaders are free to be flexible and situational (Blanchard & Hodges, 2003; Wong, 2003), because they are no longer imprisoned by their own need for power and pride.

The superiority of SL over autocratic leadership has been well documented (Farling et al., 1999; Laub, 2003; Page & Wong, 2000; Russell & Stone, 2002; Sendjaya & Sarros, 2002). SL prevents and reduces all kinds of problems directly related to command-and-control leadership. Re-engineering, restructuring, downsizing, merger, and hostile take-over strikes fear in the hearts of employees whose jobs are directly affected. Often leaders simply shuffle workers around as pawns on a chess board without ever considering how these changes might impact their lives and performance. Servant leaders can help navigate troubled waters and make inevitable changes less stressful for the employees.

Servant leaders are flexible, willing to employ different kinds of legitimate power to facilitate worker development and accomplish organizational goals (Hersey et al., 2001). However, servant leaders can and will dismiss workers whose performance and attitude negatively affect other workers in spite of repeated intervention efforts. Jack Kahl and Tom Donelan (2004) have made a strong case that servant leaders are not “sweet” and “weak”.

The main reason for the difficulty is that it requires a fundamental change of attitude and some kind of inner transformation. Most leaders are unwilling to lose their sense of control because of their own insecurity. All the exercises in team building will not make you a team person, if you are an egotistic person at heart. Egos die hard. Pride will not easily let go of its prisoners. That is why there are so few servant leaders. SL training challenges our basic attitudes and motivations. It demands a new orientation towards the self and people.

The following represents a preliminary set of best practices that may help cultivate the five major characteristics of SL. This is primarily a summary of what others have proposed (Blanchard & Hodges, 2003; Maxwell, 2005; Spears & Lawrence, 2004). The important thing emphasized here is that these best practices must be aligned with each other in order to realize the full benefits of SL.

The best practice is to embrace self-transcendence and practice its virtues:

- Cultivating humility and selflessness – Leadership is not about Me, but about the others and organization; not about my position and power, but about the wellbeing people and the success of the mission for the betterment of society.

- Cultivating responsibility – I am responsibility to the organization, to society and God, and to the people working under me. More importantly, I am responsibility for fulfilling my calling and mission.

- Having the right motivation – Reminding the self that the motivation of self-transcendence for a higher purpose should trump all competing motivations for fame, money, or power. The reason for our existence is to serve others and serve God. Practice daily the extending of a helping hand and sacrificing self-interest for the greater good. This is against the human nature of selfishness, but consistent with the nature of a higher self.

- Treating others, the right way – Guard ourselves against the popular method of treating others as instruments for self-advancement. Treat others as fellow human beings who deserve compassion. Learn to relate to others in a positive or humanistic way. Listen to others with openness and empathy rather than preaching to others. Active listening is essential for the development of understanding and sensitivity. Kouzes and Posner (1987, p. 180) declare: “Sensitivity to others is a prerequisite for success in Leadership.” Involve others in decision-making, but this does not mean that servant leaders always lead by depending on committee decisions or consensus. At times, servant leaders have to make tough and unpopular decisions, but they must consult widely and incorporate people’s input into major decisions. Servant leaders also engage others in team building and community building. Most leaders only know how to criticize but servant leaders seem to affirm others by expressing the confidence you have in them whenever possible.

- Seeking the right impact – Inspire others to serve a higher purpose by modeling the core values of self-transcendence on a daily basis (Kouzes and Posner, 1987). Challenge others to live for a higher purpose (constantly demonstrating the importance of looking at the large picture and a long-range vision). Teach people not to be too petty and too preoccupied with short-term gains). Challenging others to strive for excellence (be always a life-long learner and an eager student). Teach others the need for constant self-development.

- Demonstrating good character – Maintain integrity and authenticity by walking the talk regardless of the costs. Dare to stand up for what one believes in. Show moral fortitude to confront grim realities and pressures from higher up. Need to engage in honest examination and assessment of one’s progress in life’s journey. Openness to honest feedback and correction is critical to the Servant-Leader.

These are essential practices for a Servant-Leader to be effective. These are the qualities/practices people desire to see in their leaders. “Leadership is in the eye of the follower.” (Kouzes and Posner, 1987, p. 15). According to empirical research reviewed earlier, the best practices of SL contribute the development of all leadership characteristics, especially in matters related to the heart and character of leadership. In fact, servant leaders are more likely to attain Level 5 Leadership (Collins, 2001), which is characterized by personal humility and a fierce dedication to a larger cause.

Conclusions

It is high time to develop a new paradigm of leadership training. All the exercises on team building and strength-finding will not work without the right kind of leadership. The spirit of the leader as a servant may be just what is needed to implement a strengths-based paradigm.

The Leader of the Future from the Drucker Foundation, edited by Frances Hesselbein, Marshall Goldsmith, and Richard Beckhard (1997), rejected the command-and-control approach; they advocated the importance of learning from the grass roots and leading with a shared vision and a spirit of collaboration. They believed that the challenge facing future leaders is to serve as role models with core values and inspire a diverse work group for long-term common good. In The Leaders of the Future II, Hesselblein and Goldsmith (2006) reinforce the same themes and emphasize the need for new ideas for leadership training in the post-9/11 world. McCrimmon (2006) advocates a new kind of leadership to create the future. Such new leadership is not tied to official positions or roles; rather, it is an informal act which can be performed by all employees. Thus, every worker can show leadership by suggesting new products, better services, and more efficient processes. Toyota and Sony are shining examples of this type of bottom-up leadership.

SL is not a new concept, because it was practiced and taught by Jesus more than 2000 years ago, but it is new and revolutionary in today’s competitive consumer society. Potentially, SL can transform leadership, the workplace, and society.

Recent research provides additional support that of a trick-down model of how servant leadership affects different levels of organization. Stollberger and colleagues’ (2019) research demonstrates that manager behaviors have an extended reach and not only influence their direct reports, but act through them, and affect the work performance of employees at lower levels of an organization’s hierarchy. Their findings support a key prediction of servant leadership theory originally advanced by Greenleaf (1977), that is, whether servant leadership turns followers into servants themselves.

At the level of employee, team, and organizational performance, the trickle-down effect of servant leadership and customer-oriented performance outcomes have been empirically supported, such as customer service quality and performance (Chen et al., 2015), customer satisfaction (Yang et al., 2018), customer value co-creation (Hsiao et al., 2015), and customer-oriented prosocial behavior (Chen et al., 2015).

We suggest that building a servant leadership culture requires a combination of selecting responsible and ethical people, combined with servant leadership training. Selection is important because there is a limit to how much training can change individuals’ basic personality traits. For example, regardless of the quality of a training program, we contend that it is unlikely that individually with deeply entrenched character traits like the dark triad of psychopathology, narcissism and Machiavellianism can be trained to be self-transcendent, sensitive, empathetic servant leaders. As with virtually every major organizational change, moving an organization from a command-and-control culture to one based on servant leadership will take several years to complete, even with the most competent servant leader. Thus, organizations attempting to implement servant leadership cultures need to be patient.

At present, the Russian-Ukraine war reminds us of how urgent is to have servant leaders on the world stage. Down through history, humanity has suffered immensely because of egotistic and ruthless dictators like Hitler and Stalin. We propose that ST holds the promise of better future because it serves to balance self-enhancement. The above literature review also suggest that the best possible leadership in turbulent times is a visionary competent leader who serves others with the twin power of faith and sacrificial love. Even though it may be difficult to implement SL, society is still better served if we strive towards this ideal. All things being equal, there is a better chance of organizational success with a servant leader workers with a servant’s heart.

References

- Anderson, R. (2021). The divine feminine Tao Te Ching: A new translation and commentary. Inner Traditions.

- Bacq, S., Hartog, C., & Hoogendoorn, B. (2016). Beyond the moral portrayal of social entrepreneurs: An empirical approach to who they are and what drives them. Journal of Business Ethics, 133, 703–718.

- Barbuto, J. E., & Millard, M. L. (2014). Developing wisdom and reducing emotional labor in the workplace: Testing the impact of servant leadership. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228608842_Developing_Wisdom_and_Reducing_Emotional_Labor_in_the_Workplace_Testing_the_Impact_of_Servant_Leadership/citations

- Barbuto, J. E., Jr., & Wheeler, D. W. (2006). Scale development and construct clarification of servant-leadership. Group & Organization Management, 31(3), 300-326.

- Bass, B. (1998). Transformational leadership: Industrial, military, and educational impact. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Beerel, A. (2021). Rethinking Leadership: A Critique of Contemporary Theories. Routledge

- Blanchard, K., & Broadwell, R., eds. (2018). Servant Leadership in Action: How You Can Achieve Great Relationships and Results. Berrett-Koehler.

- Blanchard, K., & Hodges, P. (2003). The servant leader: Transforming your heart, head, hands & habits. J. Countryman.

- Bowie, N. (2000). Business ethics, philosophy, and the next 25 years. Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(1), 7-20.

- Canavesi, A., & Minelli, E. (2021). Servant Leadership and Employee Engagement: A Qualitative Study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 1–23. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-021-09389-9

- Chaudhry, A., Cao, X., Liden, R. C., Point, S., & Vidyarthi, P. R. (2021). A Meta-Review of Servant Leadership: Construct, Correlates, and the Process, Journal of Comparative International Management, 24(2), 1-26. https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/JCIM/article/view/32695

- Chen, Z., Zhu, J., & Zhou, M. (2015). How does a servant leader fuel the service fire? A multilevel model of servant leadership, individual self identity, group competition climate, and customer service performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038036

- Collins, J. C. (2001). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap…and others don’t. HarperCollins.

- Dennis, R. S., & Borcarnea, M. (2005). Development of the servant leadership assessment instrument. Leadership and Development Journal, 26(8), 600-615.

- Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Dierendonck, D., & Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

- Farling, M. L., Stone, A. G., & Winston, B. E. (1999). Servant leadership: Setting the stage for empirical research. Journal of Leadership Studies, 6, 49-72.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Washington Square Press. (First published in 1946)

- Frankl, V. E. (2020). Yes to life in spite of everything. Penguin Books. (Originally published in 1946)

- Freiberg, K., & J. (1996). Nuts! Southwest Airlines, Crazy Recipe for Business and Personal Success. Broadway Books.

- Gardner, H., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Damon, W. (2001). Good work: How excellence and ethics meet. Basic Books.

- Geher, G. (2022, February 20). Two broad paths to success in life. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/darwins-subterranean-world/202202/two-broad-paths-success-in-life

- Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

- Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press.

- Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., & Natemeyer, W. E. (2001). Situational leadership and power. In W. E. Natemeyer & J. T. McMahon (Eds.), Classics of Organizational Behavior (3rd ed.) (pp. 321- 329). Waveland Press.

- Hesselbein, F., & Goldsmith, G. (Eds.) (2006). The leader of the future 2: Visions, strategies, and practices for the new era. Jossey-Bass.

- Hesselbein, F., Goldsmith, M., & Beckhard, R. (Eds.) (1997). The leader of the future: New visions, strategies, and practices for the next era. Jossey-Bass

- Hicks, J. A., & Routledge, C. (Eds.) (2013). The experience of meaning in life: Classical perspectives, emerging themes, and controversies. Springer.

- Hine, B. N. (2008). The Hine Bibliography of Selected Monographic Resources on Servant Leadership. The Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership.

- Holiday, R. (2016). Ego is the enemy. Penguin.

- Hsiao, C., Lee, Y., & Chen, W. (2015). The effect of servant leadership on customer value co-creation: A cross-level analysis of key mediating roles. Tourism Management, 49, 45-57.

- Johnson, C. E. (2001). Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership. Sage.

- Kahl, J., & Donelan, T. (2004). Leading from the heart: Choosing to be a servant leader. Kahl & Associates.

- Kinnier, R. T., Kernes, J. L., & Dautheribes, T. M. (2000). A Short List of Universal Moral Values. Counseling and values, 45, 4-16.

- Kirby, S. (2020, June 2). 5 ways COVID-19 has changed workforce management. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/covid-homeworking-symptom-of-changing-face-of-workforce-management/

- Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1987). The leadership challenge: How to get extraordinary things done in organizations. Jossey-Bass.

- Kumar, S. (2018). Servant Leadership: A Review of Literature, Pacific Business Review International, 11 (1), 43-49.

- Laub, J. (2003). From paternalism to the servant organization: Expanding the organizational leadership assessment (OLA) model. Paper presented at the Servant Leadership Roundtable at Regent University, Virginia Beach.

- Lewis, M. W. 2000. Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Academy of Management Review, 25, 760 –776.

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006.

- Maxwell, J. C. (2005). The 360 degree leader: Developing your influence from anywhere in the organization. Thomas Nelson.

- Mayer, C. H., Wegerle, C., & Oosthuizen, R. M. (2021). Sense of Coherence in Managers during COVID-19 and the New World of Work: A Mixed-Method Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(21), 11492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111492

- McClellan, J. L. (2009). Research-Based Models of Servant-Leadership: A Review of the Literature, International Journal of Servant-Leadership, 5(1), 163-184.

- McClellan, J. L. (2010). Servant-Leadership and Organizational Outcomes: A Review of the Literature, International Journal of Servant-Leadership, 6(1), 103-122.

- McCrimmon, M. (2006). Burn! Leadership myths in flames. Self Renewal Group.

- Muyumba, V., & Hine, B. N. (2015, September). The Hine bibliography of resources on servant leadership. https://www.greenleaf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Servant-Leadership2015October13.pdf

- Page, D. (2009). Servant Empowered Leadership: A Hands-On-Guide to Transforming You and Your Organization. Power to Change Ministries.

- Page, D., & Wong, P. T. P. (2000). A conceptual framework for measuring servant leadership. In S. Adjibolosoo (Ed.), The human factor in shaping the course of history and development (pp. 69-109). University Press of America.

- Parolini, J. L. (2004). Effective servant leadership: A model incorporating servant leadership and the competing values framework. Paper presented at the Servant Leadership Roundtable, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

- Parolini, J., Patterson, K., & Winston, B. (2009). Distinguishing between transformational and servant leadership. Leadership & Organizational Development Journal, 30(3), 274-291.

- Parris, D. L., & Peachey, J. W. (2013). A Systematic Literature Review of Servant Leadership Theory in Organizational Contexts, Journal of Business Ethics. 113(3), 377-393.

- Patterson, K. (2003). Servant leadership: A theoretical model. Paper presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

- Pawar, A., Sudan, K., Satini, S., & Sunarsi, D. (2020). Organizational Servant Leadership: A Systematic Literature Review for Implications in Business. International Journal of Educational Administration, Management, and Leadership, 1(2), 63-76. https://doi.org/10.51629/ijeamal.v1i2.8

- Peck, M. S. (1978). The Road Less Travelled. Rider.

- Russell, R. F., & Stone, A. G. (2002). A review of servant leadership: Developing a practical model. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 23(3), 145-157.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online readings in psychology and culture, 2(1). Doi:10.9707/2307-0919.1116

- Searle, T. P. & Barbuto, J. E. (2010). Servant leadership, hope, and organizational virtuousness: A framework exploring positive micro and macro behaviors and performance impact. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. Doi:10.1177/1548051810383863

- Sendjaya, S. (2003). Development and validation of servant leadership behavior scale. Paper presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

- Sendjaya, S. (2015). Personal and Organizational Excellence through Servant Leadership: Learning to Serve, Serving to Lead, Leading to Transform. Springer International Publishing.

- Sendjaya, S., & Sarros, J. C. (2002). Servant leadership: Its origin, development, and application in organizations. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 9, 57-64.

- Sendjaya, S., Sarros, J., & Santora, J. (2008). Defining and measuring servant leadership behavior in organizations. The Journal of Management Studies, 45(2), 402-424.

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline. Doubleday.

- Sipe, J. W., & Frick, D. M. (2009). Seven Pillars of Servant Leadership: Practicing the Wisdom of Leading by Serving. Paulist Press.

- Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. The Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2011.59330958

- Solinger, O. N., Jansen, P. G., & Cornelissen, J. P. (2020). The Emergence of Moral Leadership. Academy of Management Review, 45, 504-527.

- Spears, L. C. (1995). Reflections on leadership. John Wiley & Sons.

- Spears, L. C., & Lawrence, M. (Eds.). (2004). Practicing servant-leadership: Succeeding through trust, bravery, and forgiveness. Jossey-Bass

- Steger, M. F. (2016). Creating meaning and purpose at work. In L. G. Oades, M. F. Steger, A. Delle Fave, & J. Passmore (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Positivity and Strengths‐Based Approaches at Work (pp. 60-81). Wiley.

- Stollberger, J., Las Heras, M., Rofcanin, Y., & Bosch, M. (2019). Serving followers and family? A trickle-down model of how servant leadership shapes employee work performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior.

- Stone, A. G., Russell, R. F., & Patterson, K. T. (2004). Transformational versus servant leadership: a difference in leader focus. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25, 349-361.

- van Dierendonck, D. (2011) Servant Leadership: A Review and Synthesis, Journal of Management, 37(4), 1228-1261.

- van Dierendonck, D., & Heeren, I. (2006). Toward a research model of servant leadership. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2(1), 147- 164.

- van Dierendonck, D., & Nuijte, K. (2011). The Servant-Leadership Survey (SLS): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Journal of Business Psychology. Doi:10, 1007/s10869-010-9194-1

- van Dierendonck, D., & Patterson, K. (2014). Compassionate Love as a Cornerstone of Servant Leadership: An Integration of Previous Theorizing and Research. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(1), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2085-z

- Widodo, S., & Suryosukmono, G. (2021). Spiritual leadership, workplace spirituality and their effects on meaningful work: Self-transcendence as mediator role. Management Science Letters, 2115-2126.

- Winston, B. E., & Ryan, B. (2008). Servant leadership as a humane orientation: using the GLOBE study construct of humane orientation to show that servant leadership is more global than western. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(2), 212-222.

- Witt, D. (2019, October 17). Research: The top 5 characteristics of servant leaders. Association for Talent Development. https://www.td.org/insights/research-the-top-5-characteristics-of-servant-leaders

- Wong, P. T. P. (2003). Spirituality and meaning at work. Positive Living Newsletter. http://www.meaning.ca/archives/presidents_columns/pres_col_sep_2003_meaning-at-work.htm

- Wong, P. T. P. (2004). The paradox of servant leadership. Leadership Link, 3-5. Ohio State University, Leadership Research Center.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2005). Creating a positive participatory climate: A meaning-centered counselling perspective. In S. Schuman (Ed.), The IAF Facilitation Handbook (pp. 171-190). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 52(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2012a). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012b). Positive Management. Presented at the 3rd Australian Conference of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, Wollongong, Australia. https://www.academia.edu/2997735/Positive_management

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Self-Transcendence: A Paradoxical Way to Become Your Best. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 6(1), 9. http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019a). Second wave positive psychology’s (PP 2.0) contribution to counselling psychology. Counselling Psychology Quarterly [Special Issue]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671320

- Wong, P. T. P. (2019b). Why and How I Developed the Positive Psychology of Suffering. Dr. Paul T. P. Wong. http://www.drpaulwong.com/why-and-how-i-developed-the-positive-psychology-of-suffering/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020a, October 21). Self-transcendence and servant leadership: From pandemic fatigue to pandemic growth. Embodiment Conference, virtual INPM Webinar presentation, Toronto, Canada.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19 According to Viktor E. Frankl and Paul T. P. Wong. INPM Press.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021a, February 4-7). Transcend the pandemic: How to redesign the future of work [Symposium]. Society of Counselling Psychology annual convention [online convention]. http://www.drpaulwong.com/transcend-the-pandemic-how-to-redesign-the-future-of-work

- Wong, P. T. P. (2021b). Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0) and global wellbeing: Why it is Necessary During the Age of COVID-19. International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology, 10(1), 1-16. https://www.meaning.ca/ijepp-article/vol10-no1/what-is-existential-positive-psychology-pp-2-0-why-is-it-necessary-for-mental-health-during-the-pandemic/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2022). Foreword. In P. Worth (Ed.), Positive Psychology Across The Life Span An Existential Perspective. Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Davey, D. (2007, July). Best practices of servant leadership. Address presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, School of Global Leadership & Entrepreneurship, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

- Wong, P. T. P., & Page, D. (2003, October 16). Servant leadership: An Opponent-Process Model and the Revised Servant Leadership Profile. Address presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, School of Global Leadership & Entrepreneurship, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

- Wong, P. T. P., Page, D., & Rude, W. (2004). Servant Leadership Profile-360 (SLP-360): Using the results. http://www.drpaulwong.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Servant-Leadership-Profile-360-SLP-360-Explanation.pdf

- Wong, P. T. P., Arslan, G., Bowers, V. L., Peacock, E. J., Kjell, O. N. E., Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T. (2021). Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the Self-Transcendence measure-B. Frontiers, 12, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648549

- Wong, P. T. P., Ivtzan, I., & Lomas, T. (2017). Good work: A meaning-centred approach. In L. G. Oades, M. F. Steger, A. Delle Fave, & J. Passmore (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of the psychology of positivity and strengths-based approaches at work (pp. 233-247). Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, P. T. P., Mayer, C.-H., & Arslan, G. (Eds.). (2021). COVID-19 and Existential Positive Psychology (PP 2.0): The new science of self-transcendence [Special Issue]. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/14988/covid-19-and-existential-positive-psychology-pp20-the-new-science-of-self-transcendence

- Worth, P. (Ed.) (2022). Positive psychology across the life span: An existential perspective. Routledge.

- Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C. R., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(1), 21–33.

- Yang, Z., Zhang, H., Kwan, H. K., & Chen, S. (2018). Crossover Effects of Servant Leadership and Job Social Support on Employee Spouses: The Mediating Role of Employee Organization-Based Self-Esteem. Journal of Business Ethics, 147, 595-604.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P., Page, T., & Cheung, T. (2022). A self-transcendence model of servant leadership. In S. Dhiman & G. Roberts (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Servant Leadership (pp. 1-26). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69802-7_58-1

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.