MEETUP 2018

Decoding Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life

This is the last of the five Meetups on “Decoding Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules of Life,” hosted by Dr. Paul Wong for the INPM’s Meaningful Living Project. For an overview of this Meetup series, see below.

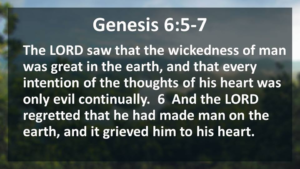

A constant refrain throughout Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life is that life is full of evil and suffering, primarily because of the human capacity for inflicting pain on others for selfish gain or ideological agendas. Self-righteous ideological battles may result in the greatest human evil, as “the worst of all possible snakes is psychological, spiritual, personal, internal” (Peterson, 2018, p. 47). No one can go through life untouched by evil and suffering.

The world is divided and polarized along racial, gender, ideological, and political lines. From the corridors of political power to the corporate boardroom, from shopping malls to gambling casinos, the world seems to be controlled by the dark forces of money, power, greed, addiction, and corruption rather than compassion and justice (Hedges, 2018). With such a dismal view of the world, one wonders if there is any hope for redemption, or any solution for the perennial problem of evil and suffering.

In spite of everything that has gone wrong in this world, Peterson is able to provide an optimistic answer by challenging people to consider an alternative heavenly trajectory: “Now you’re on a whole different kind of trajectory… You make the necessary sacrifice, and allow a whole new world of possibility, hidden from you because of your previous ambition, to reveal itself” (Peterson, 2018, p. 100).

In the first eight chapters of his book, Peterson lays down the foundation for the personal responsibility of making sacrifices and pursuing the highest good as an effective antidote to the unbearable burden of Being. In the last four rules, he outlines the simple things we can all do to alleviate unnecessary suffering and make the world a better place for ourselves and others.

At first glance, there is nothing new about the 12 rules—they seem commonplace, as they are based on traditional Judeo-Christian values and a common-sense approach to being a decent human. However, Peterson is able to inject a new sense of depth and urgency to these simple rules. He does this through the lens of Jungian archetypes and mythical narratives and a compelling neo-Darwinian argument that Western civilization will collapse under the combined weight of nihilism and totalitarianism, unless we embrace the discipline of self-sacrifice and pursue the noble goal of alleviating human suffering and enhancing moral order and transcendental values in the world.

In a consumer society of seeking comforts and pleasures, and in an academic world where young people are coddled and protected from discomfort (Lukianoff & Haidt, 2015), Peterson’s blunt language strikes a chord of responsibility among young people, especially males, who are confused, lost, helpless, and hopeless in a chaotic world that seems beyond their control. There is something very fresh and powerful in his direct and authentic voice, challenging them to stop wasting time, wandering without any direction and moral moorings, and turn away from their miserable path of resentment and self-destruction so that they can create a better future through discipline, sacrifice, and faith in the highest good in life.

In the last four chapters, the stern voice of a father figure gives way to the gentle voice of a wounded healer. Once again, Peterson reminds us that life is very hard and everyone is fighting a private battle. Therefore, let us learn to treat each other with more respect and compassion, all being in the same boat in an ocean of suffering—let us listen clearly, speak precisely, respect each other’s dignity, and be kind to all sentient beings.

Ironically, Peterson’s personal failings are most glaring in the social realm, underscoring just how difficult it is to live by these rules in social interactions. Let’s find out why these rules are important to bring a little bit of heaven to earth and how we can implement them.

Rule 9: Assume that the person you are listening to might know something you need to know

Perhaps listening is the single most important human activity. The fall of the human race was due to Adam and Eve’s failure to listen to God’s warning (Chapter 2); children can get into trouble when they refuse to listen to their parents (Chapter 5); and people mess up their lives because they fail to listen to ancient wisdom from mythical truths (Chapters 7 & 8). Therefore, learning how to listen seems a wise piece of advice towards personal and societal transformation.

Everybody is Talking, but No One is Listening

Have we lost the art of listening? How many times have you been accused of “not listening”? Sometimes, people are accused of not listening simply because they don’t agree with someone else’s opinions or demands. However, most of the time, it is because people don’t understand that listening requires one’s full attention and hard work.

Good communication is always a two-way street. If you keep on changing your statement or goal in order to justify your position, then you cannot blame the other person for not knowing what you are actually saying or what you truly want. Similarly, if you are a chronic or pathological liar, incapable of telling the truth, you also cannot blame others for turning a deaf ear towards what you say.

Here are some less obvious but more common reasons why people are not listening:

- They are not interested in your view or what you have to say;

- They do not want to understand you; they only want to make a straw man argument;

- They are only interested in imposing their agenda or ideology on you;

- They are afraid of knowing the truth, which may cause them discomfort.

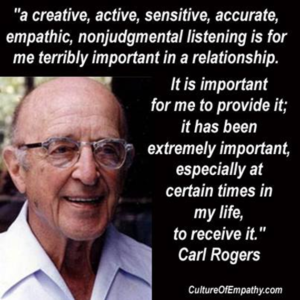

Citing Carl Rogers (1952), “The great majority of us cannot listen; we find ourselves compelled to evaluate, because listening is too dangerous,” Peterson points out that true listening is always dangerous, because change is inevitable when one is confronted with the truth that comes from authentic encounter and dialogue.

In all situations where people fail to listen, they talk over each other rather than with each other; they protect their biases and insecure self with a closed mind and well-rehearsed defense mechanisms. As a result, there is no conversation, no dialogue, no genuine exchange of information, and no discovery of truth. In short, a failure to listen will lead to increased isolation, misunderstanding, and polarization.

Learning How to Listen

Thinking is hard work; it involves an internal dialogue between two or three different views, and one has to work through all these differences in order to arrive at a correct decision. Likewise, true listening is hard because one has to understand and evaluate different views from different people before deciding on the correct view. What a rude awakening to be confronted with the brutal truth about life and ourselves! But personal growth and transformation come from painful encounters with truth (Chapter 8).

In Carl Rogers’ quote, we learn that active listening is an important but demanding task. Listening is important in marriage relationships, leadership positions, and service professions. People feel helped when someone truly listens to them without judgement. Personally, I feel that some of my clients come to see me even when they do not have any serious issues because they just need someone that is willing to listen to them and understand their struggles.

Here are some helpful suggestions from Peterson in this chapter:

1. Listen with humility and open-mindedness. When you really listen without premature judgement, people are more likely to open up and tell you what they are thinking. Thus, there is a dialogue. It is through dialogue that we learn the truth about other people and about life. Only fools think they have all the answers and that only their own way is right.

2. Learn to talk less and listen more. When you remain silent with your full attention and anticipation, you may draw out more from the person who is speaking. One of the basic skills in counselling and therapy is to remain quiet and provide a safe and supportive environment of empathy, genuineness, and unconditional acceptance. In such an environment, clients will often spontaneously reveal what is on their mind.

3. Try to summarize or paraphrase what the other person has said to make sure you understand them correctly. This is one of the powerful Rogerian techniques emphasized by Peterson.

4. Use a dialectical approach towards listening. Similar to PP 2.0, Peterson advocates this approach. We need to have the courage to pursue whatever is true, good, or meaningful, even when the truth brings us great pain. We also need to have the wisdom of balancing between the security of our self-knowledge and personhood and the risk of learning something new and disruptive:

You are where you should be, with one foot in order, and the other tentatively extended into chaos and the unknown. You are immersed in the Tao, following the great Way of Life. There, you are stable enough to be secure, but flexible enough to transform. (Peterson, 2018, p. 255)

Rule 10: Be precise in your speech

Ironically, Chapter 10 is neither precise nor clear. In some ways, it is as complex as Chapter 2. Peterson stresses that the very complexity of everything demands that we need to be precise in our speech. Unfortunately, Peterson himself has difficulty in this area. For example, he can never give a precise answer whenever people ask him whether he believes in God. He will say that it all depends on what you mean by “belief” and what you mean by “God”. His definition of God is primarily functional and metaphorical—very different from most people’s understanding of God.

If you’ve ever heard Peterson discuss the subject or read either of his books, the answers he provided in Vancouver will not surprise you. God is “how we imaginatively and collectively represent the existence and action of consciousness across time.” God is “that which eternally dies and is reborn in the pursuit of higher being and truth.” God is “the highest value in the hierarchy of values.” God is the “voice of conscience.” God is the “source of judgment and mercy and guilt.” God is the “future to which we make sacrifices and something akin to the transcendental repository of reputation.” God is “that which selects among men in the eternal hierarchy of men. (Johnson, 2018)

With regard to religious matters, his opacity enables him to expand people’s understanding of God and at the same time avoid being pigeonholed into any religious group, even though most of his religious and psychological insights are based on the Bible. However, even in psychological matters, his penchant to analyse issues to the nth degree of complexity makes it difficult for him to express his ideas precisely according to the customary practice of scientific journals. I am sure that most journal editors and reviewers would ask Peterson to simplify his language and provide empirical support.

The genius of Peterson is that he can penetrate any issue in a deeper and more precise way than most psychologists. Anyone who has attended his lectures can witness that he often struggles to find the right words to express his profound thoughts in a way that his audience can understand. This chapter is a good example of his difficult, deep, but inspiring way of writing and speaking.

Here is an attempt to summarize this very complex chapter. Peterson makes the point that the world is far more complex than we realize; therefore, one should not claim to have a single-cause solution to all problems. Furthermore, technology is changing so quickly, and everything is built for obsolescence; this another reason why you should not impose your own solutions on the world. Thirdly, you even do not know yourself, because people are complicated creatures. You need to sort yourself out in order to know precisely what you want for your future. Such efforts are necessary to shed some light in the darkness and complexity of human existence.

“The world reveals itself to us as something to utilize and something to navigate through, not as something that merely is” (Peterson, 2018, p. 261). More importantly, what the world reveals to us depends on our end values and our beliefs. When we look at the world, we only perceive its functional utility for us to carry out our plans and achieve our goals. In other words, we live in such a complex, multidimensional world with all its hidden interactions, that we can only perceive what serves our purposes. “It is for this reason that we must be precise in our aim. Absent that, we drown in the complexity of the world” (Peterson, 2018, p. 262).

Apart from finding the preferred path and living a meaningful life, speaking in a clear and precise way in everyday conversations matters a great deal in interpersonal relationships. Most misunderstandings, arguments, and conflicts occur when one…

- talks carelessly, spewing out unfiltered thoughts;

- talks about something beyond one’s depth or understanding;

- doesn’t have the vocabulary or the correct words;

- speaks in a tentative and ambiguous manner to avoid contentious issues;

- speaks from a different perspective or frame of reference.

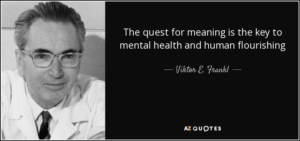

Meaning and Existential Crisis

When things are going well, people may not bother with meaning in their lives. But when things are falling apart, when the world no longer behaves the way we expect, and when our understanding and expertise are no longer sufficient for the emerging chaos, we experience an existential crisis. “The thin veneer of perceptual sufficiency cracks, however, when something fundamental goes wrong. The dreadful inadequacy of our senses reveals itself. Everything we hold dear crumbles to dust. We freeze” (Peterson, 2018, p. 267). This crisis may be triggered by a tragic accident, getting fired from one’s job, or seeing one’s marriage on the rocks.

Avoiding our existential crisis only makes things worse—the monster lurking beneath may grow bigger and bigger. “Why avoid, when avoidance necessarily and inevitably poisons the future?” (Peterson, 2018, p. 275). That’s why you need to confront the painful reality and your own inadequacy. The sooner the better. You need to have the courage to peer into the darkness, accept life’s suffering, and specify the problem so that it can be resolved.

Focus On What Really Matters and Make it Simple

“Everything clarified and articulated becomes visible” (Peterson, 2018, p. 274). In order to not be overwhelmed and confused, you need to do some soul searching, practice critical reflection, and really sort yourself out. To keep things simple and focused, you need to figure out what really matters and to articulate your needs and intentions in precise and clear terms. This is how you can resolve your existential crisis and avoid unnecessary conflicts at home and in society. This piece of advice is similar to the one given by Confucius.

This reminds me of Friedman’s (2016) book, Thank You for Being Late. Friedman discusses how the planet’s three largest forces—Moore’s law (technology), the market (globalization), and Mother Nature (climate change and biodiversity loss)—are accelerating all at once. To overcome these multiple stressors in an age of acceleration, we need to slow down and reflect on the possibilities and dangers.

According to Peterson, the real danger of the above epochal changes in the 21st century is an existential vacuum, which invites nihilism and anarchy on the one hand, and totalitarianism and government control on the other hand. These materialistic and atheistic ideologies threaten the moral foundation of Western civilization.

Peterson’s answer to our existential crisis is twofold: We need to reorient ourselves and aim at life’s highest good, and we need to assume personal responsibility to confront our problems courageously, then decide in precise terms what we want to become. Aiming high will bring out the best in us. The spiritual vision of a transcendental reality will automatically narrow the infinite possibilities to a manageable number and determine what the world will reveal to you. A clear sense of personal responsibility will empower you to move forward towards your life goals, despite all the obstacles and uncertainties.

You Need to be Precise in Your Language

“Why refuse to specify, when specifying the problem would enable its solutions?” (Peterson, 2018, p. 276). Specifying the problem means that you acknowledge the problem exists, define your failure, and identify what needs to be done in order to have a better future, no matter how painful the process. “The alternative to that single sharp pain is the dull aches of continued hopelessness and failure and the sense that time, precious time, is slipping by” (Peterson, 2018, p. 276).

You need to use precise language to specify what really troubles you and identify what really matters in your life. “In that collapse into the terrible mess of uncomprehended Being lurks the possibility of new and benevolent order. Clarity of thought—courageous clarity of thought—is necessary to call it forth” (Peterson, 2018, p. 279).

Clear thinking in the midst of chaos and accelerated changes requires hard work and mental discipline. You need to be very careful with the language you use internally and have courage and honesty in sorting out yourself. It may take many days or even weeks of soul searching and inner struggle before you are able to specify your new life goal in concrete, precise terms. Then, you need to articulate your new plan with your friends so that they can witness and reinforce your transformation.

Conclusion

The complicated process of finding a precise answer to our existential crisis as described in this chapter may be framed in terms of Wong’s (2016) ABCDE strategy in meaning therapy.

Acceptance—Accept the fact that something horrible has shattered our false sense of self-sufficiency and our assumptive world. The ancient defensive reflex kicks in; we freeze. We pause and reflect on what has gone wrong.

Belief—We believe that from the current disruption and chaos, some new opportunity will emerge. We believe that by broadening our horizon and investigating new alternatives, we may achieve a deeper understanding of reality and re-establish order. “Why refuse to investigate, when knowledge of reality enables mastery of reality?” (Peterson, 2018, p. 275).

Commitment—We need to have the courage to confront the chaos, our brokenness, and our dark side. We must be committed to getting to the bottom of the matter, and specify exactly what went wrong, no matter how painful the process. It is a commitment to a narrow path of sacrifice and carrying the cross voluntarily.

Discovery—We need to discover what went wrong and the values that can be sustained even in the worst tragedies. We need to discover something worth fighting and dying for, then specify our discovery in precise speech. “Search for the correct words. Organize these words into the correct sentences, and those sentences into correct paragraphs. The past can be redeemed, when reduced by precise language to its essence. The present can flow by without robbing the future if its realities are spoken out clearly” (Peterson, 2018, p. 281).

Enjoyment/evaluation—When we say what we mean and do what we say, we will have the satisfaction of being authentic and maintaining good relationships. When we are not afraid of correcting our mistakes and striving towards a better future, we will experience the deep satisfaction of re-birth and the meaning of life, which will also protect us from suffering. If the joy of fulfillment still eludes us, then we will go through another iteration of ABCDE at a deeper level.

Precise language will shape and sharpen our perception of reality; it will also facilitate problem-solving, goal-attainment, and relationship development. That being said, it would be naïve to believe that being precise in our speech about our ultimate concerns and life goals will resolve all our predicaments in life. However, the precise articulation of our problems and aspirations is still a good indication of having sorted ourselves out and started on a new trajectory. In Chapter 8, we learn why we need to tell the truth. In this chapter, we learn how to speak the truth as a way to create better relationships and a better future.

Confront the chaos of Being. Take aim against a sea of troubles. Specify your destination and chart your course. Admit to what you want. Tell those around you who you are. Narrow, and gaze attentively, and move forward, forthrightly. (Peterson, 2018, p. 283)

Rule 11: Do not bother children when they are skateboarding

This is the most political and controversial chapter, in which Peterson details his case against identity politics in general and postmodern feminism in particular. Interestingly, there seems to be more documentation of research support in this chapter than other chapters. Most of Peterson’s reputation and following are based on his success as a cultural warrior rather than as a psychologist. His first breakthrough in fighting against political correctness and feminism came from his knockout performance in an interview with Cathy Newman, which has been viewed by millions of people (NeoUnrealist, 2018). This was followed by a series of successful debates over cultural Marxism, postmodern feminism, and the importance of religious faith (Brierley, 2018).

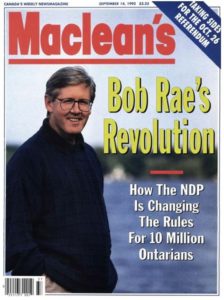

It is beyond my area of competency and the scope of my objectives to assess the validity of his political and philosophical views on neo-Marxism and postmodernism (see his views on these issues here). However, I do empathize with his concerns, and I can understand why occasionally he goes ballistic in his rants against the radical left, because of my own personal experience with campus radical activism at Trent University, in Ontario, Canada.

Campus Activism in the Early 90s

When Bob Rae was the NDP Premier of Ontario (October 1990 – June 1995), I personally experienced the horrors of cultural Marxism. First, Bob Rae issued a policy of zero tolerance, forbidding professors to teach anything that may offend any students. The faculty at Trent led the pushback against this policy, because university education was supposed to challenge students’ ignorance and unexamined beliefs, a process inherently threatening to their insecurity.

Second, the student leadership decided to stop funding all Christian clubs on campus, including Intervarsity Christian Fellowship and Chinese Christian Fellowship, due to the fact that Christianity was a privileged religion in Canada. Therefore, all the money was now redirected to less advantaged clubs, such as the Islamic Group and the LGBT Club.

Third, a radical Rainbow coalition stormed into a room where the President’s Commission on Sexual Harassment had their weekly meeting for two months. I was one of the members on this commission, and we had already examined relevant documents from many sources and interviewed numerous individuals. When we were having our last meeting and in the process of completing our recommendations, about 20 young people led by a big black man stormed in and declared that the Commission was illegitimate because there was no coloured member on the Commission, and I was not considered a coloured minority. They demanded every Commission member to sign a document prepared by the Coalition to disband the Commission. The Vice-President who chaired the Commission dutifully signed the document without any protest, as did the other Commission members. I was the only one who refused to sign, and the black student physically threatened me.

These experiences have left an indelible mark on me and made me fearful of how oppressive and anti-Christian our society can be when a socialist government is in control. The idealism in our young people needs to be encouraged and reinforced. I am grateful that Peterson is able to expose the dark and dangerous secrets of the “progressive” ideology of socialism and redirect the idealism of younger generations to personal responsibility and heroism against harsh fate and social injustice.

Another important lesson I have learned is that it is not possible to reason or have a civilized dialogue with the radical left because they only understand the language of power, however way such power is gained and exercised. By all the rules and logic of higher education, there is no other way to explain the extraordinary power of the Rainbow coalition to nullify all the work done by a properly instituted Commission with members from Administration, Faculty, Staff, and Students.

Danger and Mastery

I am very familiar with the west side of Sidney Smith Hall at the University of Toronto, where Peterson watched crazy boys skateboard without protective equipment. “Just before they collided with the handrail, they would reach down, grab their board with a single hand and jump onto the top of the rail, board sliding their way down its length, propelling themselves off and landing” (Peterson, 2018, p. 285).

Skateboarding requires the courage of taking the risk to fall and get hurt. It also demands a great deal of practice before one can master the skill. “They wanted to triumph over danger… They were trying to become competent—and it’s competence that makes people as safe as they can truly be” (Peterson, 2018, p. 286).

Kids need sports risky enough to remain challenging. “We’re hard-wired, for that reason, to enjoy risk (some of us more than others). We feel invigorated and excited when we work to optimize our future performance, while playing in the present” (Peterson, 2018, p. 287).

Recently, a series of steel brackets known as “skatestoppers” were installed every two or three feet along the edges of St. George Street on the east side of Sidney Smith. Peterson saw this ugly installation to stop skateboarders from doing their highly skilled acts as “the operation of an insidious and profoundly anti-human spirit” (Peterson, 2018, p. 290).

This observation serves as the platform for launching his views on a wide range of gender issues and identity politics. The “skatestoppers” serve as a metaphor for all the insidious political restrictions against the human spirit of creativity, curiosity, and adventure.

Let Boys Be Boys

We all recognize that boys are different from girls—generally, they are more independent, rambunctious, and risk-taking. These developmental characteristics of boys may be rooted in evolutionary biology and culture. They should not be punished for their failing to conform to the female ideal of being nice and gentle. Unfortunately, “boys are suffering in the modern world” (Peterson, 2018, p. 298) and Peterson has marshaled a lot of empirical evidence to support this claim:

As privileged beneficiaries of the patriarchy, their accomplishments are considered unearned. As possible adherents of rape culture, they are sexually suspect. Their ambitions make them plunderers of the planet. They’re not welcome. At the junior high, high school, and university level, they’re falling behind educationally. (Peterson, 2018, p. 297)

80% of students in the fields of healthcare, public administration, psychology and education are females… At this rate, there will be very few men in most university disciplines in fifteen years. This is not good news for me… But it’s also not good news for women. (Peterson, 2018, p. 299)

The decline in high-paying manufacturing jobs for men (one of six men of employable age is currently without work in the US)… the unemployed working man is an undesirable specimen—and single motherhood an undesirable alternative. (Peterson, 2018, p. 301)

If we don’t let boys be boys, there will not be any real men for women. Discrimination against boys is bad news not only for both males and females, but also for children. “Children in father-absent homes are four times as likely to be poor… Fatherless children are at much greater risk for drug and alcohol abuse… Children in single-parent families are twice as likely to commit suicide” (Peterson, 2018, p. 302).

Peterson’s diagnosis of why boys are languishing socially and academically is consistent with several books on the same topic, such as Christina Sommers’ War Against Boys (2015), Leona Sax’s Boys Adrift (2016), and Warren Farrell’s Boy Crisis (2018) and The Myth of Male Power (1996).

According to Bradley (2018), Peterson has a unique understanding of the problems confronting boys and young men and offers them hope:

A large percentage of men born after 1990 already felt weak, beaten down, and worthless. Young men needed empathetic pastors to build them up to be the men that God created them to be. Jordan Peterson is the prophet who understands this reality. As an observant Jungian and college professor, Peterson knows that thirty years of raising men in a culture that destroyed the archetypal, aspirational Jesus needs the antidote of empathy, encouragement, and practical day-to-day imagination to help men recover their souls so that they can live a life that means something.

Men’s Movement

What is a real man? What is healthy masculinity?

To my understanding, a real man is not afraid to be himself, someone who is comfortable in his own skin. He is tough enough to take on hard jobs, but humble enough to ask for help when he needs it. He has the courage to face harsh reality, including his own vulnerabilities and shadowy parts. He is as dependable as a rock, yet as flexible as water. He walks with his head held high even when he is walking through dark valleys. He is hard-headed for facts and reasons, but tender-hearted towards all people.

According to Peterson, such a man is the product of a loving family, strict moral teaching, heroic role models, and overcoming many difficulties for character development. Unfortunately, there has been a steady decline of manhood in the last 30 years, partly due to changing economic conditions, and partly due to the rise of feminism.

A number of publications indicate that there has been a backlash against the feminist movement in the last 30 years, such as Helen Smith’s (2015) Men on Strike, Michael Kimmel’s (2017) Angry White Men, and Scott Greer’s (2017) No Campus for White Men. In addition, there have been various men’s movements since the early 1990s.

First, there are Jungian-influenced writers, such as Robert Bly’s Iron John (2015) and Robert Moore’s and Douglas Gillette’s (2001) King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine. Their books continue to provide inspiration to men who need help.

Then there is “Promise Keepers”, an evangelical organization that challenges men to remain true to their promises of chastity and marital fidelity. Peterson’s appeal is that he combines Jungian archetypes with Biblical teachings to challenge males to embrace their masculinity and reject feminist derogative narratives about men.

The sex differences between males and females have been well-documented by research. Why can’t we just forget the gender warfare and appreciate men’s natural tendency towards courageous risk-taking and willingness to make sacrifices and women’s gift to be attractive and nurturing?

Toxic masculinity as expressed in violence and predatory sexual behaviour and toxic femininity as seen in exhibitionism and seduction represent the exploitation of biological differences for egotistic gains. The emphasis should be on developing healthy masculinity and femininity.

Men have to toughen up. Men demand it, and women want it, even though they may not approve of the harsh and contemptuous attitude that is part and parcel of the socially demanding process that fosters and then enforces that toughness. (Peterson, 2018, p. 331)

Patriarchy—Natural or Evil?

In Myth of Male Power, Farrell challenges the belief that men had more power and argues that the gender differences are rooted in biology and socialization. He writes that, historically, both sexes were disposable in the service of survival: women risked death in childbirth; men risked death in war. Through socialization, men’s role was defined as making money and supporting the family, while women’s role was to give birth and raise children.

Similarly, Peterson observes that “throughout history, men and women both struggled terribly for freedom from the overwhelming horrors of privation and necessity. Women were often at a disadvantage during that struggle… with the extra reproductive burden and less physical strength” (Peterson, 2018, pp. 303-304). Therefore, such biological differences, rather than male oppression, is the reason why most cultures are patriarchal rather than matriarchal, and why boys behave like boys. It is both wrong and dangerous to teach on campuses that our culture is the result of male oppression.

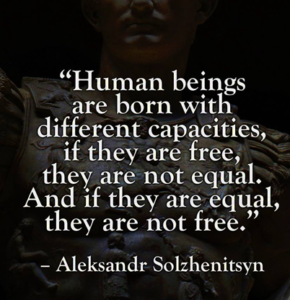

Peterson also argues that patriarchy is just another form of dominance hierarchy, which is an inevitable natural phenomenon. There is nothing wrong with hierarchy, even though it always creates winners and losers. Dominance hierarchy has adaptive advantages and contributes to our well-being, because

(1) the collective pursuit of any valued goal procures a hierarchy… and (2) it is the pursuit of goals that in large part lends life its sustaining meaning. We experience almost all the emotions that make life deep and engaging as a consequence of moving successfully towards something deeply desired and valued … Absolute equality would therefore require the sacrifice of value itself—and then there would be nothing worth living for. (Peterson, 2018, p. 303)

Worse still, absolute equality has to be enforced by an all-powerful government or ruling class; this in itself would represent the worst case of inequality and totalitarianism, because tyranny takes away citizens’ basic human right—the freedom of self-expression and self-determination.

Steven Pinker’s (2018) Enlightenment Now supports Peterson’s case for dominance hierarchy. He too thinks that inequality is natural and good for human progress. Marxism, socialism, and any totalitarian system is bad for human progress, because in a closed system of perfect social order, entropy will set in, resulting in more chaos over time.

In contrast, in a liberal democracy, individuals’ endeavour to improve their lives through their existential struggles and heroic efforts in the marketplace will result in a better life for themselves and others in a “fallen” world.

However, Peterson’s worldview offers more hope than Pinker’s humanistic liberalism. In addition to a common emphasis on the singularity of individuals and their potential for making a unique contribution, Peterson also argues that individuals’ heroic efforts yield the best results when they are aimed at the highest good in life. Such transcendental values can be seen in the Judeo-Christian narrative.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, Peterson prefers the singularity of individuals to the intersectionality of groups, for four reasons: (1) When we endlessly divide people into groups in terms of advantages and disadvantages, we eventually end up with the individual as the nexus of all possible dimensions; (2) to regard people in terms of group identity will encourage class-struggle and deeper polarization as advocated by Marxism; (3) to punish individuals simply because of personal resentment and past grievances towards any group because of some real or perceived privileges is unfair; and (4) we like others to see us as unique individuals rather than a member of a particular group according to a prevalent group stereotype. Therefore, let’s treat others as unique human beings.

Considering the atrocities against humanity in the name of socialism and communism, liberal democracy remains the best economic-political system, in spite of its messiness, chaos, and problems with an income gap, violence, and addiction. The main advantage of a democratic society is that it grants individuals the freedom to pursue their own dreams while respecting other people’s rights and dignity.

Democracy allows us to find our own path and discover our higher calling through both painful failures and deep satisfaction in our successes. It is our choice and responsibility to grow and flourish, each in our own way in spite of all the obstacles and risks. This is possible only when there is no intruding government or oppressive ideology to place “skatestoppers” in our path of adventure. We experience meaning and joy only in our heroic struggles for a better life for the self and others against the gravity of entropy and chaos.

It is sad that many idealistic young people in North American still prefer equality to freedom because they have been brainwashed by the teachings of cultural Marxism on so many campuses. These young people have no idea what it would be like to live in a totalitarian regime, nor do they know that in Communist countries, there is neither equality nor freedom. They should remember the brutal murder of hundreds of university students in Tiananmen Square and the arrest and imprisonment of Nobel literature laureate Liu Xiaobo. Worse still, in addition to the loss of human rights and freedom, income inequality is bigger in China than in the US or Canada.

To underscore the danger of totalitarian Communism, I want to end this chapter with Peterson’s (2018b) forward to the 50th anniversary edition of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago:

The socialists (the Soviets, Chinese, N. Koreans, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Cubans, etc.) murdered over 100 million people during just 79 years of the 20th century (from 1918 to 1991). Murder was their main achievement, as well as the enslavement of millions and terrorizing millions more. This man’s sayings are not trivial. We will never know the depth of hardship he endured to give us a chance… a glimpse behind the facade and Potemkin village view of the real horror of socialism and the depth of depravity that socialists are prone to. Have others done wicked and evil deeds? Of course, but they all pale by comparison with the scale and magnitude of the depravity of the Soviet Union, Communist China, N. Korea, Cuba, Cambodia, etc.

Rule 12: Pet a cat when you encounter one on the street

Peterson rounds up this provocative book with a strangely titled chapter on petting a cat. But it is a fitting conclusion, revealing a tender and compassionate side of Peterson behind his serious exterior, stringent voice, and combative spirit. You can almost feel an aching heart, coming from his personal experience of watching his own daughter Mikhaila suffer from disintegration and pain for eight long years.

From the vantage point of a wounded healer, he sees humanity as a miserable species desperately in need of love and compassion. All the preceding chapters are important in moving us towards the right direction from the dark bottom of despair and miseries. We need to have a defiant attitude against a cruel fate and an unshakable faith in our own intrinsic worth and dignity as human beings so that we can crawl out of the abyss and get ourselves established by aiming high and striving to improve our place in the dominance hierarchy. We need to stand tall and man up to our problems with courage and faith. We need to have wisdom and follow moral rules to live in a polarized world.

Even when things go reasonably well, life is hard. However, when a catastrophe strikes, when our entire world collapses around us, it will test whether we have built enough character strength to survive the blow. This chapter focuses on whether we have sufficiently sorted ourselves out to survive and thrive through traumas that throw our lives in utter disorder.

Suffering and the Limitations of Being

Once again, Peterson returns to his main leitmotiv with a flourish: Life is full of suffering, and human beings are fragile.

We can be damaged, even broken, emotionally and physically, and we are all subject to the depredations of aging and loss. This is a dismal set of facts, and it is reasonable to wonder how we can expect to thrive and be happy (or even to want to exist, sometimes) under such conditions. (Peterson, 2018, p. 338)

What shall we do when we face the tragedies of human existence, when we are tired of living and striving, when we feel helpless and hopeless in our dire circumstances, so much so that we want to end this unbearable existence?

This is exactly what I have raised repeatedly as the proper question for existential positive psychology (Wong, 2016a), or PP 2.0 (Wong, 2011, 2015). Most of my answers can be found in my research on tragic optimism (Wong, 2009), existential positive interventions (Wong, 2016b), and mature happiness (Wong & Bowers, 2018). It is gratifying that Peterson has come to very similar conclusions.

To me, the real challenge for positive psychology should be: How can we be at our best, when life is at its worst? How can we soar above all the hardships and traumas in a splendid display of the noble and defiant human spirit? How can we still experience joy and happiness, even when nothing goes right, and our problems will not go away? Chapter 12 represents Peterson’s last installment in answering this challenge.

Accepting the Dark Side of Existence

In our pain and desperation, it is only natural that we would question, “What sort of God would make a world where such a thing could happen?” (Peterson, 2018, p. 340). “How can reality be structured so unbearably? How can this be?” (Peterson, 2018, p. 346). On a personal level, it is only natural what we would ask, “Why this? Why me? What have I done to deserve it?”

We can think of little innocent children dying from cancer and their grieving parents, or random violence and mass killings at schools. On a larger scale, we can think of the millions of people that have perished in Hitler’s final solution, Stalin’s political purges, and Mao’s cultural revolution. There is no rational explanation for such monstrous horrors. “I don’t think it is possible to answer the question by thinking. Thinking leads inexorably to the abyss. When existence reveals itself as existentially intolerable, thinking collapses in on itself” (Peterson, 2018, p. 347).

Peterson found his answer in accepting suffering as an inherent part of existence that requires no explanation. “My realization of the tight interlinking between vulnerability and Being was the best answer I had… There is something to be said for recognizing that existence and limitation are inextricably linked” (Peterson, 2018, p. 343). This is just the way life is. For everything good that exists, there must be some limitation.

Once we understand the principle of acceptance, we will be liberated from all our resentments and complaints about our limitations in finances, social spheres, physical attributes, or intelligence and academic aptitudes. Such acceptance is balanced by our continued efforts to improve ourselves (Chapter 4).

The principle of acceptance will also help us understand the inherent limitations in every stage of development: (a) helpless, dependent children fight against parental control to test their limits; (b) adolescents struggle to find their own identity and secure their place in academic competitions; (c) adults have to fight against internal and external constraints to get established; and (d) old people have to fight against their own decline and demise. A lot of suffering comes from these natural limitations in the process of development.

Even God has Limitations

“A superhero who can do anything turns out to be no hero at all… He has nothing to strive against, so he can’t be admirable. Being of any reasonable sort appears to require limitation. Perhaps this is because Being requires Becoming, as well as mere static existence” (Peterson, 2018, p. 345). This insight leads Peterson to conclude that even the almighty God has his limitations, because he could not do anything about humanity’s blind willfulness in disobeying his basic rule, resulting in their expulsion from the Garden of Eden and the ushering in of human evils.

God’s failure was that he created man with a free will, because man chose to rebel against him rather than obey him, thus opening the floodgate of evil. God’s plan of redemption is to bring us back to himself through the sacrificial love of Christ and through all the tragedies of human existence.

I am grateful that through God’s failure, we learn the all-important lesson that no matter how intelligent and powerful we become, we can create hell for ourselves and others if we play the role of God and do not recognize him as both the highest good and the greatest authority on what is good and right. In other words, free will without a function to obey and worship God is the beginning of all human evils.

This lesson is also relevant to the future of artificial intelligence (AI). In his latest book, Stephen Hawking and colleagues (2018) warns of the dangers of unrestricted growth in AI and manipulations of DNA to create superhumans. On one hand, he does not believe there is God; on the other hand, he warns that we are courting self-destruction when we create robots and superhumans. The obvious answer to this dilemma is that new developments need to have a built-in function of “acting as if God exists” as a moral and ethical restraint.

Life Intelligence to Get Through the Chaos of Traumas

When you are devastated by a major life event, be it the death of a loved one, the diagnosis of terminal illness, or a natural disaster, you still have to cope with the demands of everyday life in addition to the chaos brought on by the trauma. To avoid being overwhelmed, “set aside some time to talk and think about the illness or other crisis… Conserve your strength. You’re in a war, not a battle, and a war is composed of many battles. You must stay functional through all of them” (Peterson, 2018, p. 351).

“Shift the unit of time you use to frame your life…” (Peterson, 2018, p. 351). If you are used to thinking in terms of years, you may now have to think in terms of months or even weeks if you have just been told that you only have a few months to live. The shrinking of your horizon forces you to make good choices and decide what should be your ultimate concern when everything has been taken away from you. Even in our weakest moments, we can still leave a word of wisdom and love to those we leave behind.

Living each day fully does not simply mean focusing only on the present moment. It means having the courage to “place faith in God’s Heavenly Kingdom, and the truth. That’s a conscious decision to presume the primary goodness of being… Once you are aligned with the heavens, you can concentrate on the day” (Peterson, 2018, p. 351). This calls for the use of the double-vision strategy in meaning therapy (Wong, 2016b)—to keep one eye on what we can do at the moment, another eye on our spiritual vision of Heaven.

“Repair what is in disorder and make what is already good better” (Peterson, 2018, p. 351). Don’t just focus on what is broken; you also need to develop what is already good. This dual-system approach (Wong, 2012) is the most effective way to make you stronger.

Develop an appreciative attitude towards life. The world will reveal whatever you are seeking. Search for what is good, true, and beautiful, and you will find something that lifts up your spirit, even when you are going through a terrible time. Remember Frankl’s moment of joy when he glimpsed the beauty of a sunset while in a Nazi death camp (Frankl, 1985).

Life is Hard; Therefore, be Kind to Someone

“If you pay careful attention, even on a bad day, you may be fortunate enough to be confronted with small opportunities of petting a cat, seeing a little girl dancing on the street, or having a good cup of coffee in customers-friendly café” (Peterson, 2018, p. 353). There is something beautiful and profound about gently petting a cat in the street. It is not just about happiness, although I can imagine a positive psychologist would publish a paper on how “Petting an animal can make you happy.”

In an outstretched arm and the tender touch of a street cat, this simple symbolic gesture speaks volumes of Peterson’s idea of Heaven on earth. The good life is (a) finding a sanctuary of peace in the middle of a storm (Wong & Bowers, 2018); (b) being connected with nature, all sentient beings, and the Creator in perfect harmony; and (c) reaching out to the less advantaged with compassion. In that magic moment of connection, we become fully human—as we transcend all egotistic interests and the differences that divide us—in our attempt to embrace the sacredness of life as the common ground (Wong, 2016c).

Conclusion

Throughout the entire book, Peterson leads us through the vast terrain of suffering—the dark valleys and the steep mountains—without circumventing difficult controversial issues. In brutal effectiveness, he dismantles cultural Marxism and postmodern feminism, which have misled numerous idealistic young people. He then articulates an alternative vision of personal responsibility; his 12 rules are designed to challenge people to bring order to their own lives in a chaotic world so that they can grow and become what they were meant to be.

Like a cyclist, life is balancing act. Peterson’s 12 rules summarize the life intelligence we all need in order to maintain a precarious dynamic balance between opposite forces as we move forward, in spite of the ups and downs of life. It takes wisdom and courage to manage order and chaos so that we neither become stagnant in our security, nor become disintegrated or burnt-out in over-expanding ourselves. Life is an endless cycle of order and chaos, Being and Becoming, as a way to build enough character strength and resilience to survive the worse dramas and produce our fruits.

Given this dynamic and dialectic process of balancing opposites, I don’t think that climbing the ladder of dominance hierarchy represents Jordan Peterson’s end value for a good life, because at the very top, there is the insecurity of being replaced and the empty feeling of having nothing more to conquer. Peterson’s neo-Darwinian view of the struggle to improve one’s ranking in the dominance hierarchy is always balanced by a spiritual vision of aiming at the highest good of reaching out to lift up those who are downtrodden, as taught by the Bible.

The symbolic act of petting a street cat is a metaphor of picking up one’s cross to pursue the narrow path of self-sacrifice and aim at the kingdom of God. If the lobster represents the masculinity of competition, the cat represents the femininity of compassion. At the end, the process of sorting out is concerned not so much about our place in a competitive world, but how we order society so that we can all live together in harmony and mutual respect. Human progress depends on how we resolve the tension between our inner lobster (or dominance hierarchy) and inner divinity (or agape love for all sentient beings). The following quote seems to suggest that in the highest level of human development in an ideal society, our inner God will expand, and our inner lobster will decline.

At the end of Rule 6 on “Set your house in perfect order”, Peterson wishfully entertains the notion that,

“if all people did this, in their own lives, the world might stop being an evil place… Who knows what existence might be like if all decide to strive for the best? Who knows what eternal heavens might be established by our spiritus, purified by truth, aiming skyward, right here on the fallen Earth?” (Peterson, 2018, p. 199)

There is a quantum jump from sorting one’s self out and finding one’s place in the world to establishing a harmonious social order. Most likely, such a social order would be modeled after the agape love of God’s kingdom rather than totalitarian socialism. Peterson himself has not been able to find a way to have dialogue and cooperation with others to co-create a better world. Perhaps, the missing piece can be found in the symbolic gesture of petting a street cat—the moment of both finding our humanity and losing our egotistic pride in reaching out to those who suffer.

Similarly, Abraham Maslow (1971) also recognized that self-actualization cannot be the end-game; in his revised needs hierarchy, the highest achievement is self-transcendence—losing one’s self in serving a higher purpose and helping others to become their best. Thus, the transition from self-actualization to self-transcendence represents a hero’s ultimate balancing act with one foot in improving one’s dominance hierarchy and another foot in using one’s gift to serve others. That is why a compassionate and responsible liberal democracy offers the most promising hope for us to become our best.

References

- Bly, R. (2015). Iron John: A book about men. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press.

- Bradley, A. (2018, February 12). The voice evangelical men wish they had. Fathom Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.fathommag.com/stories/the-voice-evangelical-men-wish-they-had

- Brierley, J. (2018, July). Is Jordan B Peterson the saviour of Christianity? Premier Christianity. Retrieved from https://www.premierchristianity.com/Past-Issues/2018/July-2018/Is-Jordan-B-Peterson-the-saviour-of-Christianity

- Farrell, W. G. (1996). The myth of male power. New York, NY: Berkley Books.

- Farrell, W. G. (2018). Boy crisis: Why our boys are struggling and what we can do about it. New York, NY: Benbella Books.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

- Friedman, T. L. (2016). Thank you for being late: An optimist’s guide to thriving in the age of accelerations. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

- Greer, S. (2017). No campus for white men: The transformation of higher education into hateful indoctrination. Los Angeles, CA: WND Books.

- Lukianoff, G., & Haidt, J. (2015). The coddling of the American mind. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/09/the-coddling-of-the-american-mind/399356/

- Hawking, S., Redmayne, E., Thorne, K. S., & Hawking, L. (2018). Brief answers to the big questions. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

- Hedges, C. (2018). America: The farewell tour. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Johnson, M. (2018, July 23). The peculiar opacity of Jordan Peterson’s religious views. Retrieved from https://quillette.com/2018/07/23/the-peculiar-opacity-of-jordan-petersons-religious-views/

- Kimmel, M. S. (2017). Angry white men: American masculinity at the end of an era. New York, NY: Nation Books.

- Maslow, A. H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York, NY: Viking Press.

- Moore, R. L., & Gillette, D. (2001). King, warrior, magician, lover: Rediscovering the archetypes of the mature masculine. San Francisco, CA: Harper.

- [NeoUnrealist]. (2018, January 18). Jordan Peterson Goes Beast Mode in Interview by Cathy Newman Chan 4 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuqDuSJVNV0

- Peterson, J. B. (2018a). 12 rules for life: An antidote to chaos. Toronto, ON: Vintage Canada.

- Peterson, J. B. (2018b). Foreword. In Solzhenitsyn, Gulag Archipelago. London, UK: Vintage Classics.

- Pinker, S. (2018). Enlightenment now: A manifesto for science, reason, humanism, and progress. London, UK: Allen Lane.

- Rogers, C. R. (1952). Communication: Its blocking and its facilitation. ETC: A review of General Semantics, 9, 83-88.

- [Ruminate]. (2017, July 6). Postmodernism and Cultural Marxism | Jordan B Peterson [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLoG9zBvvLQ

- Sax, L. (2016). Boys adrift: The five factors driving the growing epidemic of unmotivated boys and underachieving young men. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Smith, H. (2015). Men on strike: Why men are boycotting marriage, fatherhood, and the American dream—and why it matters. New York, NY: Encounter Books.

- Sommers, C. H. (2015). War against boys: How misguided policies are harming our young men. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2009). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany, & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker, & Theisen.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology, 52(2), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3-22). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015). What is second wave positive psychology and why is it necessary? Paul T. P. Wong. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/what-is-second-wave-positive-psychology-and-why-is-it-necessary/

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016a). Existential positive psychology. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/179/158

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016b). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & A. Batthyány (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323-342). New York, NY: Springer.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016c). Self-transcendence: A paradoxical way to become your best. International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 6(1). Retrieved from http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178/141

- Wong, P. T. P. & Bowers, V. (2018). Mature happiness and global wellbeing in difficult times. In N. R. Silton (Ed.), Scientific concepts behind happiness, kindness, and empathy in contemporary society(pp. 112-134). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Cite

Wong, P. T. P. (2018, October 23). 4 simple things everyone can do to make the world better (Meetup 2018, Lesson 5). INPM. Retrieved from http://www.drpaulwong.com/4-simple-things-everyone-can-do-to-make-the-world-better/

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.

Meaning Conference 2025 will be the INPM’s first in-person conference with a virtual option after the pandemic.